Word Borrowing and Code Switching in Ancash Waynu Songs∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forms and Functions of Negation in Huaraz Quechua (Ancash, Peru): Analyzing the Interplay of Common Knowledge and Sociocultural Settings

Forms and Functions of Negation in Huaraz Quechua (Ancash, Peru): Analyzing the Interplay of Common Knowledge and Sociocultural Settings Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Cristina Villari aus Verona (Italien) Berlin 2017 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Dürr 2. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Ingrid Kummels Tag der Disputation: 18.07.2017 To Ani and Leonel III Acknowledgements I wish to thank my teachers, colleagues and friends who have provided guidance, comments and encouragement through this process. I gratefully acknowledge the support received for this project from the Stiftung Lateinamerikanische Literatur. Many thanks go to my first supervisor Prof. Michael Dürr for his constructive comments and suggestions at every stage of this work. Many of his questions led to findings presented here. I am indebted to him for his precious counsel and detailed review of my drafts. Many thanks also go to my second supervisor Prof. Ingrid Kummels. She introduced me to the world of cultural anthropology during the doctoral colloquium at the Latin American Institute at the Free University of Berlin. The feedback she and my colleagues provided was instrumental in composing the sociolinguistic part of this work. I owe enormous gratitude to Leonel Menacho López and Anita Julca de Menacho. In fact, this project would not have been possible without their invaluable advice. During these years of research they have been more than consultants; Quechua teachers, comrades, guides and friends. With Leonel I have discussed most of the examples presented in this dissertation. It is only thanks to his contributions that I was able to explain nuances of meanings and the cultural background of the different expressions presented. -

Languages of the Middle Andes in Areal-Typological Perspective: Emphasis on Quechuan and Aymaran

Languages of the Middle Andes in areal-typological perspective: Emphasis on Quechuan and Aymaran Willem F.H. Adelaar 1. Introduction1 Among the indigenous languages of the Andean region of Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, northern Chile and northern Argentina, Quechuan and Aymaran have traditionally occupied a dominant position. Both Quechuan and Aymaran are language families of several million speakers each. Quechuan consists of a conglomerate of geo- graphically defined varieties, traditionally referred to as Quechua “dialects”, not- withstanding the fact that mutual intelligibility is often lacking. Present-day Ayma- ran consists of two distinct languages that are not normally referred to as “dialects”. The absence of a demonstrable genetic relationship between the Quechuan and Aymaran language families, accompanied by a lack of recognizable external gen- etic connections, suggests a long period of independent development, which may hark back to a period of incipient subsistence agriculture roughly dated between 8000 and 5000 BP (Torero 2002: 123–124), long before the Andean civilization at- tained its highest stages of complexity. Quechuan and Aymaran feature a great amount of detailed structural, phono- logical and lexical similarities and thus exemplify one of the most intriguing and intense cases of language contact to be found in the entire world. Often treated as a product of long-term convergence, the similarities between the Quechuan and Ay- maran families can best be understood as the result of an intense period of social and cultural intertwinement, which must have pre-dated the stage of the proto-lan- guages and was in turn followed by a protracted process of incidental and locally confined diffusion. -

Emotion, Ethics and Intimate Spectacle in Peruvian Huayno Music

Andean Divas: Emotion, Ethics and Intimate Spectacle in Peruvian Huayno Music James Robert Butterworth Music Department Royal Holloway, University of London Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 Declaration of Authorship I, James Robert Butterworth, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ________________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Abstract This thesis examines the self-fashioning and public images of star divas that perform Peruvian huayno music. These divas are both multi-authored stories about a person as well as actually existing individuals, occupying a space between myth and reality. I consider how huayno divas inhabit and perform a range of subject positions as well as how fans and detractors fashion their own sense of self in relation to such categories of experience. I argue that the ways in which divas and fans inhabit and reject different subject positions carry strong emotional and ethical implications. Combining multi-sited fieldwork in the music industry with analyses of songs, media representations and public discourses, I locate huayno divas in the context of Andean migration and attendant narratives about suffering, struggle, empowerment and success. I analyse huayno performances as intimate spectacles, which generate acts of both empathy and voyeurism towards the genre’s star performers (Chapter 2). The tales of romantic suffering and moral struggle contained in huayno songs, which provide a key source of audience engagement, are brought to life through the voices and bodies of huayno divas (Chapter 3). -

(REELA) 5-7 September 2015, Leiden University Centre for Linguistics

Fourth Conference of the Red Europea para el Estudio de las Lenguas Andinas (REELA) 5-7 September 2015, Leiden University Centre for Linguistics Fourth Conference of the European Association for the Study of Andean Languages - Abstracts Saturday 5 September Lengua X, an Andean puzzle Matthias Pache Leiden University In the southern central Andes, different researchers have come across series of numerals which are difficult to attribute to one of the language groups known to be or have been spoken in this area: Quechuan, Aymaran, Uru-Chipayan, or Puquina (cf. Ibarra Grasso 1982: 97-107). In a specific chapter headed “La lengua X”, Ibarra Grasso (1982) discusses different series of numerals which he attributes to this language. Although subsumed under one heading, Lengua X, the numerals in question may vary across the sources, both with respect to form and meaning. An exemplary paradigm of Lengua X numerals recorded during own fieldwork is as follows: 1 mayti 2 payti 3 kimsti 4 taksi 5 takiri 6 iriti 7 wanaku 8 atʃ͡atʃ͡i 9 tʃ͡ipana 10 tʃ͡ˀutx Whereas some of these numerals resemble their Aymara counterparts (mayti ‘one’, payti ‘two’, cf. Aymara maya ‘one’, paya ‘two’), others seem to have parallels in Uru or Puquina numerals (taksi ‘four’, cf. Irohito Uru táxˀs núko ‘six’ (Vellard 1967: 37), Puquina tacpa ‘five’ (Torero 2002: 454)). Among numerals above five, there are some cases of homonymy with Quechua/Aymara terms referring to specific entities, as for instance Lengua X tʃ͡ipana ‘nine’ and Quechua/Aymara tʃ͡ipana ‘fetter, bracelet’. In this talk, I will discuss two questions: (1) What is the origin of Lengua X numerals? (2) What do Lengua X numerals reveal about the linguistic past of the southern central Andes? References Ibarra Grasso, Dick. -

On the External Relations of Purepecha: an Investigation Into Classification, Contact and Patterns of Word Formation Kate Bellamy

On the external relations of Purepecha: An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Kate Bellamy To cite this version: Kate Bellamy. On the external relations of Purepecha: An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation. Linguistics. Leiden University, 2018. English. tel-03280941 HAL Id: tel-03280941 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03280941 Submitted on 7 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/61624 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Bellamy, K.R. Title: On the external relations of Purepecha : an investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Issue Date: 2018-04-26 On the external relations of Purepecha An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Published by LOT Telephone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht Email: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Kate Bellamy. ISBN: 978-94-6093-282-3 NUR 616 Copyright © 2018: Kate Bellamy. All rights reserved. On the external relations of Purepecha An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation PROEFSCHRIFT te verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. -

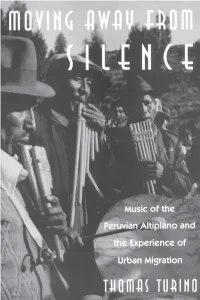

Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experiment of Urban Migration / Thomas Turino

MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE CHICAGO STUDIES IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Bruno Nettl EDITORIAL BOARD Margaret J. Kartomi Hiromi Lorraine Sakata Anthony Seeger Kay Kaufman Shelemay Bonnie c. Wade Thomas Turino MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THOMAS TURlNo is associate professor of music at the University of Ulinois, Urbana. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1993 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1993 Printed in the United States ofAmerica 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 1 2 3 4 5 6 ISBN (cloth): 0-226-81699-0 ISBN (paper): 0-226-81700-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Turino, Thomas. Moving away from silence: music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the experiment of urban migration / Thomas Turino. p. cm. - (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology) Discography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Folk music-Peru-Conirna (District)-History and criticism. 2. Folk music-Peru-Lirna-History and criticism. 3. Rural-urban migration-Peru. I. Title. II. Series. ML3575.P4T87 1993 761.62'688508536 dc20 92-26935 CIP MN @) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. For Elisabeth CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: From Conima to Lima -

The Attributive Suffix in Pastaza Kichwa

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2020-06-08 The attributive suffix in Pastaza Kichwa Barrett Wilson Hamp Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hamp, Barrett Wilson, "The attributive suffix in Pastaza Kichwa" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 8443. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8443 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Attributive Suffix in Pastaza Kichwa Barrett Wilson Hamp A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Janis Nuckolls, Chair Chris Rogers Jeff Parker Department of Linguistics Brigham Young University Copyright © 2020 Barrett Wilson Hamp All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Attributive Suffix in Pastaza Kichwa Barrett Wilson Hamp Department of Linguistics, BYU Master of Arts This thesis is a corpus-based description of the attributive suffix -k in Pastaza Kichwa, a Quechuan language spoken in lowland Amazonian Ecuador. The goal of this work is, first, to describe the behaviors, characteristics, and functions of the suffix using data from the Corpus of Pastaza Kichwa (Rice 2018a), and second, to offer a typological analysis of these behaviors in order to identify the most appropriate classification for the suffix. The suffix has previously been described as a nominalizer (Nuckolls & Swanson, forthcoming), and the equivalent suffix in other Quechuan varieties has been described as an agentive nominal relativizer (Weber 1983; Weber 1989; Cole 1985; Lefebvre & Muysken 1988) or a participle (Markham 1864; Weber 1989; Guardia Mayorga 1973; Catta Quelen 1985; Debenbach-Salazar Saenz 1993, Muysken 1994). -

Staging Lo Andino: the Scissors Dance, Spectacle, and Indigenous Citizenship in the New Peru

Staging lo Andino: the Scissors Dance, Spectacle, and Indigenous Citizenship in the New Peru DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason Alton Bush, MA Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Lesley Ferris, Co-Advisor Katherine Borland, Co-Advisor Ana Puga Copyright by Jason Bush 2011 Abstract “Staging Lo Andino: Danza de las Tijeras, Spectacle, and Indigenous Citizenship in the New Peru,” draws on more than sixteen months of fieldwork in Peru, financed by Ohio State‟s competitive Presidential Fellowship for dissertation research and writing. I investigate a historical ethnography of the Peruvian scissors dance, an acrobatic indigenous ritual dance historically associated with the stigma of indigeneity, poverty, and devil worship. After the interventions of Peruvian public intellectual José María Arguedas (1911-1969), the scissors dance became an emblem of indigenous Andean identity and valued as cultural patrimony of the nation. Once repudiated by dominant elites because it embodied the survival of indigenous spiritual practices, the scissors dance is now a celebrated emblem of Peru‟s cultural diversity and the perseverance of Andean traditions in the modern world. I examine the complex processes whereby anthropologists, cultural entrepreneurs, cosmopolitan artists, and indigenous performers themselves have staged the scissors dance as a symbolic resource in the construction of the emergent imaginary of a “New Peru.” I use the term “New Peru” to designate a flexible repertoire of utopian images and discourses designed to imagine the belated overcoming of colonial structures of power and the formation of a modern nation with foundations in the Pre-Columbian past. -

Música Chicha.Pdf

MÚSICA CHICHA La música tropical andina en la ciudad de Cuzco Hubert Ramiro Cárdenas Ediciones Interculturalidad.org Lima, Perú, setiembre 2014 Música chicha La música tropical andina en la ciudad de Cuzco. © Cárdenas, Hubert Ramiro © Ediciones Interculturalidad.org www.interculturalidad.org 1ª ed. Digital. Lima / Perú, setiembre, 2014 Coordinación de edición: Arturo Quispe Lázaro. Carátula: Manuel Víctor Guevara Valencia, artista plástico Se autoriza la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra siempre y cuando se mencione la fuente y se respete el derecho de autor. iv ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN ix CAPÍTULO I. HISTORIA DE LA MÚSICA CHICHA EN EL PERÚ 1 1.1. Acercamiento al proceso migratorio en el Perú 1 1.2. Asociaciones de provincianos 5 1.3. Uso de la radio por el sector migrante popular 10 1.4. Programas folclóricos 11 1.5. La música en el Perú de los años sesenta 13 1.6. Música chicha 16 1.6.1. Nacimiento de la música chicha 16 1.6.2. Música chicha en la década del ochenta 21 1.6.3. De la música tropical andina a la tecnocumbia 25 1.6.4. Ocaso de la tecnocumbia 31 1.6.5. Cumbia norteña: la chicha del siglo XXI 33 1.6.6. Clasificación de la música chicha 37 CAPÍTULO II. HISTORIA DE LA MÚSICA TROPICAL ANDINA EN LA CIUDAD DE CUZCO 40 2.1. Antecedentes: crecimiento urbano y modernización 40 2.2. Configuración del sector popular 45 2.3. Arribo de la música chicha 48 2.4. Música tropical andina 51 v 2.5. Sobre la agrupación de cumbia andina 55 2.5.1. -

A Grammar of Yauyos Quechua

A grammar of Yauyos Quechua Aviva Shimelman language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 9 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath Consulting Editors: Fernando Zúñiga, Peter Arkadiev, Ruth Singer, Pilar Valen zuela In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. ISSN: 2363-5568 A grammar of Yauyos Quechua Aviva Shimelman language science press Aviva Shimelman. 2017. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua (Studies in Diversity Linguistics 9). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/83 © 2017, Aviva Shimelman Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-946234-21-0 (Digital) 978-3-946234-22-7 (Hardcover) 978-3-946234-23-4 -

Applying Finite-State Techniques to a Native American Language: Quechua

Institut f¨urComputerlinguistik Herbstsemester 2010 Universit¨atZ¨urich Applying Finite-State Techniques to a Native American Language: Quechua Lizentiatsarbeit der Philosphischen Fakult¨at der Universit¨atZ¨urich Referent: Prof. Dr. Martin Volk Verfasserin: Annette Rios Bachtelstrasse 32 8620 Wetzikon Matrikelnummer 03{703{634 arios@ifi.uzh.ch 2 Abstract Comprehensive finite-state morphology systems have been developed for numer- ous languages, nevertheless the American indigenous languages have received far less attention from the computational linguistic field than the standard European languages. For this thesis, I implemented a complete morphology system for the Andean language Quechua. Dealing with a non-standardized indigenous language of low social prestige and sparsely available resources imposes serious challenges on the development of computational linguistic tools. Nevertheless, I will show that finite-state techniques are perfectly suited to capture the relatively complex mor- phological structures of Quechua, once the linguistic processes determining word formation have been unravelled. Acknowledgments I'm grateful to many persons who helped me during the writing of this thesis. First of all, I'd like to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Martin Volk for his support and constructive critics. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr. Simon Clematide, who provided the technical support on the xfst implementation with a considerable amount of patience. I'd like to thank native Quechua speaker Marisol Pillco Grajeda from Cusco, who kept answering my questions over and over again. I am grateful to Anne G¨ohringfor reading through the complete thesis and pointing out the remaining deficiencies. A big thank you goes to my sister Melanie Chenoweth for proof-reading the final script. -

Exploring Phonological Areality in the Circum-Andean Region Using a Naive Bayes Classifier

Exploring phonological areality in the circum-Andean region using a naive Bayes classifier Lev Michael, Will Chang, and Tammy Stark This paper describes the Core and Periphery technique, a quantitative method for exploring areality that uses a naive Bayes classifier, a statistical tool for inferring class membership based on training sets assembled from members of those classes. The Core and Periphery technique is applied to the exploration of phonological areality in the Andes and surrounding lowland regions, based on the South American Phonological Inventory Database (SAPhon 1.1.3; Michael et al., 2013). Evidence is found for a phonological area centering on the Andean highlands, and extending to parts of the northern and central Andean foothills regions, the Chaco, and Patagonia. Evidence is also found for Southern and North-Central phonological sub-areas within this larger phonological area. Keywords: naive Bayes classifier; linguistic areality; Andean languages; South American languages 1. Introduction The goals of this paper are to describe the Core and Periphery technique, an intuitively appealing quantitative method for exploring large linguistic datasets for evidence of linguistic areality, and to illustrate the utility of this technique by applying it to a dataset of South American phonological inventories, focusing on the evidence of phonological areality in the Andes and surrounding lowland areas. Core and Periphery is a method that uses as a starting point linguists’ knowl- edge of the languages and history of a region to generate initial hypotheses regarding ‘cores’: sets of languages that constitute possible linguistic areas (Campbell et al., 1986; Thomason, 2000; Muysken, 2008), or parts of ones.