Forms and Functions of Negation in Huaraz Quechua (Ancash, Peru): Analyzing the Interplay of Common Knowledge and Sociocultural Settings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relación De Agencias Que Atenderán De Lunes a Viernes De 8:30 A. M. a 5:30 P

Relación de Agencias que atenderán de lunes a viernes de 8:30 a. m. a 5:30 p. m. y sábados de 9 a. m. a 1 p. m. (con excepción de la Ag. Desaguadero, que no atiende sábados) DPTO. PROVINCIA DISTRITO NOMBRE DIRECCIÓN Avenida Luzuriaga N° 669 - 673 Mz. A Conjunto Comercial Ancash Huaraz Huaraz Huaraz Lote 09 Ancash Santa Chimbote Chimbote Avenida José Gálvez N° 245-250 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Calle Nicolás de Piérola N°110 -112 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Rivero Calle Rivero N° 107 Arequipa Arequipa Cayma Periférica Arequipa Avenida Cayma N° 618 Arequipa Arequipa José Luis Bustamante y Rivero Bustamante y Rivero Avenida Daniel Alcides Carrión N° 217A-217B Arequipa Arequipa Miraflores Miraflores Avenida Mariscal Castilla N° 618 Arequipa Camaná Camaná Camaná Jirón 28 de Julio N° 167 (Boulevard) Ayacucho Huamanga Ayacucho Ayacucho Jirón 28 de Julio N° 167 Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Jirón Pisagua N° 552 Cusco Cusco Cusco Cusco Esquina Avenida El Sol con Almagro s/n Cusco Cusco Wanchaq Wanchaq Avenida Tomasa Ttito Condemaita 1207 Huancavelica Huancavelica Huancavelica Huancavelica Jirón Francisco de Angulo 286 Huánuco Huánuco Huánuco Huánuco Jirón 28 de Julio N° 1061 Huánuco Leoncio Prado Rupa Rupa Tingo María Avenida Antonio Raymondi N° 179 Ica Chincha Chincha Alta Chincha Jirón Mariscal Sucre N° 141 Ica Ica Ica Ica Avenida Graú N° 161 Ica Pisco Pisco Pisco Calle San Francisco N° 155-161-167 Junín Huancayo Chilca Chilca Avenida 9 De Diciembre N° 590 Junín Huancayo El Tambo Huancayo Jirón Santiago Norero N° 462 Junín Huancayo Huancayo Periférica Huancayo Calle Real N° 517 La Libertad Trujillo Trujillo Trujillo Avenida Diego de Almagro N° 297 La Libertad Trujillo Trujillo Periférica Trujillo Avenida Manuel Vera Enríquez N° 476-480 Avenida Victor Larco Herrera N° 1243 Urbanización La La Libertad Trujillo Victor Larco Herrera Victor Larco Merced Lambayeque Chiclayo Chiclayo Chiclayo Esquina Elías Aguirre con L. -

Redalyc.Railroads in Peru: How Important Were They?

Desarrollo y Sociedad ISSN: 0120-3584 [email protected] Universidad de Los Andes Colombia Zegarra, Luis Felipe Railroads in Peru: How Important Were They? Desarrollo y Sociedad, núm. 68, diciembre, 2011, pp. 213-259 Universidad de Los Andes Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=169122461007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista 68 213 Desarrollo y Sociedad II semestre 2011 Railroads in Peru: How Important Were They? Ferrocarriles en el Perú: ¿Qué tan importantes fueron? Luis Felipe Zegarra* Abstract This paper analyzes the evolution and main features of the railway system of Peru in the 19th and early 20th centuries. From mid-19th century railroads were considered a promise for achieving progress. Several railroads were then built in Peru, especially in 1850-75 and in 1910-30. With the construction of railroads, Peruvians saved time in travelling and carrying freight. The faster service of railroads did not necessarily come at the cost of higher passenger fares and freight rates. Fares and rates were lower for railroads than for mules, especially for long distances. However, for some routes (especially for short distances with many curves), the traditional system of llamas remained as the lowest pecuniary cost (but also slowest) mode of transportation. Key words: Transportation, railroads, Peru, Latin America. JEL classification: N70, N76, R40. * Luis Felipe Zegarra is PhD in Economics of University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). -

Avance De La Implementación

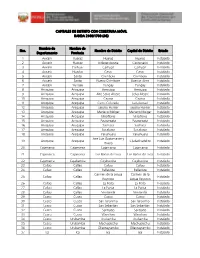

CAPITALES DE DISTRITO CON COBERTURA MÓVIL BANDA 2100/1700 (4G) Nombre de Nombre de Nro. Nombre de Distrito Capital de Distrito Estado Departamento Provincia 1 Ancash Huaraz Huaraz Huaraz Instalado 2 Ancash Huaraz Independencia Centenario Instalado 3 Ancash Carhuaz Carhuaz Carhuaz Instalado 4 Ancash Huaylas Caraz Caraz Instalado 5 Ancash Santa Chimbote Chimbote Instalado 6 Ancash Santa Nuevo Chimbote Buenos Aires Instalado 7 Ancash Yungay Yungay Yungay Instalado 8 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Instalado 9 Arequipa Arequipa Alto Selva Alegre Selva Alegre Instalado 10 Arequipa Arequipa Cayma Cayma Instalado 11 Arequipa Arequipa Cerro Colorado La Libertad Instalado 12 Arequipa Arequipa Jacobo Hunter Jacobo Hunter Instalado 13 Arequipa Arequipa Mariano Melgar Mariano Melgar Instalado 14 Arequipa Arequipa Miraflores Miraflores Instalado 15 Arequipa Arequipa Paucarpata Paucarpata Instalado 16 Arequipa Arequipa Sachaca Sachaca Instalado 17 Arequipa Arequipa Socabaya Socabaya Instalado 18 Arequipa Arequipa Yanahuara Yanahuara Instalado Jose Luis Bustamante y 19 Arequipa Arequipa Ciudad Satelite Instalado Rivero 20 Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Instalado 21 Cajamarca Cajamarca Los Baños del Inca Los Baños del Inca Instalado 22 Cajamarca Cajabamba Cajabamba Cajabamba Instalado 23 Callao Callao Callao Callao Instalado 24 Callao Callao Bellavista Bellavista Instalado Carmen de la Legua Carmen de la 25 Callao Callao Instalado Reynoso Legua Reynoso 26 Callao Callao La Perla La Perla Instalado 27 Callao Callao La Punta La Punta Instalado 28 Callao Callao Ventanilla Ventanilla Instalado 29 Cusco Cusco Cusco Cusco Instalado 30 Cusco Cusco San Jeronimo San Jeronimo Instalado 31 Cusco Cusco San Sebastian San Sebastian Instalado 32 Cusco Cusco Santiago Santiago Instalado 33 Cusco Cusco Wanchaq Wanchaq Instalado 34 Cusco Urubamba Urubamba Urubamba Instalado 35 Cusco Urubamba Machupicchu Machupicchu Instalado 36 Cusco Urubamba Ollantaytambo Ollantaytambo Instalado 37 Ica Ica Ica Ica Instalado Nombre de Nombre de Nro. -

Semantic Transparency in the Lowland Quechua Morphosyntax

Semantic transparency in Lowland Ecuadorian Quechua morphosyntax1 PIETER MUYSKEN Abstract In this paper the properties of Lowland Ecuadorian Quechua, a possibly pidginized variety from this Andean indigenous language family, are eval- uated in the light of the semantic-transparency hypothesis. It is argued that the typological perspective created by looking at a wider range of languages brings some of the basic ideas developed for creole languages into focus. 1. Introduction One of Pieter Seuren’s contributions to the field of creole studies has been the idea that creoles somehow represent semantically transparent structures, as a result of their special history. Together with the late Herman Wekker, Seuren has particularly elaborated this idea in their joint 1986 paper. The dimensions of semantic transparency proposed by Seuren and Wekker (1986: 64) are uniformity, universality, and simplicity. Furthermore, Pieter Seuren has repeatedly stressed the importance of typological considerations, most recently in his Western Linguistics (1998). In this brief paper I will start to illustrate the workings of the principle of semantic transparency for the possibly pidginized Quechua of the Amazonian lowlands of eastern Ecuador, Lowland Ecuadorian Quechua (LEQ). This variety has been described by Leonardi (1966) and Mugica (1967) and is represented in texts gathered by Oberem and Hartmann (1971), but the present paper is based mostly on my own fieldwork in Arajuno (Tena province). Quechua is spoken (by more than eight million speakers) mostly in rural areas of the highlands of Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador, but small pockets of speakers are also found on the slopes of the Amazon basin of Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, and Ecuador. -

Text Segmentation by Language Using Minimum Description Length

Text Segmentation by Language Using Minimum Description Length Hiroshi Yamaguchi Kumiko Tanaka-Ishii Graduate School of Faculty and Graduate School of Information Information Science and Technology, Science and Electrical Engineering, University of Tokyo Kyushu University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract addressed in this paper is rare. The most similar The problem addressed in this paper is to seg- previous work that we know of comes from two ment a given multilingual document into seg- sources and can be summarized as follows. First, ments for each language and then identify the (Teahan, 2000) attempted to segment multilingual language of each segment. The problem was texts by using text segmentation methods used for motivated by an attempt to collect a large non-segmented languages. For this purpose, he used amount of linguistic data for non-major lan- a gold standard of multilingual texts annotated by guages from the web. The problem is formu- lated in terms of obtaining the minimum de- borders and languages. This segmentation approach scription length of a text, and the proposed so- is similar to that of word segmentation for non- lution finds the segments and their languages segmented texts, and he tested it on six different through dynamic programming. Empirical re- European languages. Although the problem set- sults demonstrating the potential of this ap- ting is similar to ours, the formulation and solution proach are presented for experiments using are different, particularly in that our method uses texts taken from the Universal Declaration of only a monolingual gold standard, not a multilin- Human Rights and Wikipedia, covering more than 200 languages. -

Languages of the Middle Andes in Areal-Typological Perspective: Emphasis on Quechuan and Aymaran

Languages of the Middle Andes in areal-typological perspective: Emphasis on Quechuan and Aymaran Willem F.H. Adelaar 1. Introduction1 Among the indigenous languages of the Andean region of Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, northern Chile and northern Argentina, Quechuan and Aymaran have traditionally occupied a dominant position. Both Quechuan and Aymaran are language families of several million speakers each. Quechuan consists of a conglomerate of geo- graphically defined varieties, traditionally referred to as Quechua “dialects”, not- withstanding the fact that mutual intelligibility is often lacking. Present-day Ayma- ran consists of two distinct languages that are not normally referred to as “dialects”. The absence of a demonstrable genetic relationship between the Quechuan and Aymaran language families, accompanied by a lack of recognizable external gen- etic connections, suggests a long period of independent development, which may hark back to a period of incipient subsistence agriculture roughly dated between 8000 and 5000 BP (Torero 2002: 123–124), long before the Andean civilization at- tained its highest stages of complexity. Quechuan and Aymaran feature a great amount of detailed structural, phono- logical and lexical similarities and thus exemplify one of the most intriguing and intense cases of language contact to be found in the entire world. Often treated as a product of long-term convergence, the similarities between the Quechuan and Ay- maran families can best be understood as the result of an intense period of social and cultural intertwinement, which must have pre-dated the stage of the proto-lan- guages and was in turn followed by a protracted process of incidental and locally confined diffusion. -

Puntos De Recaudo Pagoefectivo En Agentes Kasnet - Provincia

Puntos de Recaudo PagoEfectivo en Agentes Kasnet - Provincia Departamento Provincia Distrito Localidad Nombre del Comercio Dirección Referencia AMAZONAS BAGUA COPALLIN COPALLIN BOTICA JC FARMA FRANCISCO BOLOGNESI 533 MEDIA CUADRA DEL MERCADO AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA BAGUA BAZAR LOCUTORIO ANGELICA JR. COMERCIO 524 FRENTE A PARQUE PRINCIPAL AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA BAGUA BOTICA SANIDAD J&S JR. RODRIGUEZ DE MENDOZA 442 ENTRE LA PLAZA PRINCIPAL Y EL BANCO DE LA NACION AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA LA PECA TELECOMUNICACIONES LURVI JR. LIMA PT. INT. 3 MERCADO LA PARADA AMAZONAS BONGARA FLORIDA FLORIDA MULTISERVICIOS J & G AV. MARGINAL S/N CD 2 FRENTE A CAJA PIURA Y A DOS CUADRAS DE COMISARIA AMAZONAS CHACHAPOYAS CHACHAPOYAS CHACHAPOYAS COSELVI JR. SALAMANCA 900 A CUADRA Y MEDIA DE LA PLAZA DE ARMAS AMAZONAS UTCUBAMBA BAGUA GRANDE BAGUA GRANDE LOCUTORIO MOVITEL PARADA MUNICIPAL PUESTO 14 FRENTE A FERRETERIA CHAVEZ AV MARIANO MELGAR AMAZONAS UTCUBAMBA BAGUA GRANDE BAGUA GRANDE MOTO REPUESTOS MENDOZA AV. CHACHAPOYAS N. 1688 FRENTE A LA UGEL BAGUA GRANDE AMAZONAS UTCUBAMBA BAGUA GRANDE BAGUA GRANDE TELECOMUNICACIONES & SERVICIOS SFA AV. CHACHAPOYAS 2294 COST. COOP. CRISTO DE BAGAZAN ANCASH CARHUAZ CARHUAZ CARHUAZ MULTISERTEL G Y M AV. PROGRESO 684 ESQUINA PLAZA DE ARMAS ANCASH CASMA CASMA CASMA JAVELI OFFICE SCHOOL AV. NEPEÑA MZ. B LT. 1 FRENTE AL BANCO DE LA NACION ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ COMPEX PERU AV. FITZCARRAL 304 ESQUINA CON JR. CARAZ ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ COMPUNET JR. JUAN DE LA CRUZ ROMERO 451 FRENTE AL MERCADO CENTRAL ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ ENKANTOS BOUTIQUE JR JULIAN DE MORALES 709 FRENTE A LA FACULTAD DE MINAS ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ IMPORTACIONES TINA JR JOSE DE SAN MARTIN 571 A MEDIA CUADRA DEL PARQUEO ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ INVERSIONES DENNYS JR. -

Intonation in Quechua: Questions and Analysis

INTONATION IN QUECHUA: QUESTIONS AND ANALYSIS Erin O’Rourke University of Pittsburgh [email protected] ABSTRACT information about the peaks and valleys occurring in non-final position within the utterance. Research on the suprasegmental system of Quechua has largely focused on the placement of 2. BACKGROUND stress within a word. Previous descriptions of Quechua intonation found in the literature offer a Quechua is an agglutinative language with SOV schematic representation of the intonation contour. word order which is spoken by approximately 8 In order to examine Quechua intonation within the million people primarily in Peru, Bolivia and current framework of Autosegmental Metrical Ecuador and also in parts of Argentina, Colombia (AM) phonology, data from field recordings in and Chile [2]. The Quechuan language family can Cuzco of Southern Peruvian Quechua have been be divided into two main varieties, Central and analyzed. The current paper offers a preliminary Peripheral [8, 15]. In Peru the Peripheral variety sketch of the basic units of intonation employed in with the greatest number of speakers is Southern Quechua, including pitch accents and boundary Peruvian Quechua [3]. Cuzco Quechua, one of the tones. This analysis may provide additional data in Southern Peruvian varieties, has been chosen for the cross-comparison of intonation systems and this description of intonation given its large also aid in the task of applying the principals of the distribution of speakers. AM model to less-commonly studied intonation 3. STRESS IN QUECHUA systems. Quechua has a fixed location for primary stress. As noted in Cerrón-Palomino [2:128], research on Keywords: intonation, Autosegmental Metrical Quechua suprasegmentals has focused mainly on (AM) model, Quechua, pitch accent, boundary stress placement across different varieties: “The tone phenomena of accent, rhythm and intonation are 1. -

Only and Focus in Imbabura Quichua 1

Only and focus in Imbabura Quichua Jos Tellings University of California, Los Angeles⇤ 1 Introduction This paper investigates the interaction of focus and the exclusive particle -lla ‘only’ in Im- babura Quichua. Imbabura Quichua (henceforth Quichua)1 is a Quechuan language spoken in Imbabura Province in Northern Ecuador. Quichua is a highly agglutinative, suffixing language with a predominantly verb-final word order. A 2008 estimate of the number of speakers is 150,000 (G´omez-Rend´on 2008:182fn.). Existing literature on this language in- cludes one descriptive grammar (Cole 1982), whereas most theoretical work on this language is directed towards (morpho)syntax (Cole and Hermon 1981; Hermon 2001; Willgohs and Farrell 2009), and its evidential system (to be discussed in section 2.2 below) (see S´anchez 2010:236↵. for a more exhaustive bibliography on the Quechuan languages). The study of focus in Quichua is worthwhile for a number of reasons. First, as I will dis- cuss in a little more detail in section 2.1 below, Quichua is a relatively uncommon language from a point of view of focus typology, because it realizes focus non-phonologically, and it has a bound morpheme exclusive particle -lla. The semantic study of focus is still domi- nated by English and other languages that realize focus by phonological means. Studying a typologically marked language will be insightful in testing our theory for cross-linguistic validity. Second, this work contributes to an existing body of research on the suffix -mi which appears in several Quechuan languages, and which belongs to perhaps the best studied parts of the Quechuan language family. -

(REELA) 5-7 September 2015, Leiden University Centre for Linguistics

Fourth Conference of the Red Europea para el Estudio de las Lenguas Andinas (REELA) 5-7 September 2015, Leiden University Centre for Linguistics Fourth Conference of the European Association for the Study of Andean Languages - Abstracts Saturday 5 September Lengua X, an Andean puzzle Matthias Pache Leiden University In the southern central Andes, different researchers have come across series of numerals which are difficult to attribute to one of the language groups known to be or have been spoken in this area: Quechuan, Aymaran, Uru-Chipayan, or Puquina (cf. Ibarra Grasso 1982: 97-107). In a specific chapter headed “La lengua X”, Ibarra Grasso (1982) discusses different series of numerals which he attributes to this language. Although subsumed under one heading, Lengua X, the numerals in question may vary across the sources, both with respect to form and meaning. An exemplary paradigm of Lengua X numerals recorded during own fieldwork is as follows: 1 mayti 2 payti 3 kimsti 4 taksi 5 takiri 6 iriti 7 wanaku 8 atʃ͡atʃ͡i 9 tʃ͡ipana 10 tʃ͡ˀutx Whereas some of these numerals resemble their Aymara counterparts (mayti ‘one’, payti ‘two’, cf. Aymara maya ‘one’, paya ‘two’), others seem to have parallels in Uru or Puquina numerals (taksi ‘four’, cf. Irohito Uru táxˀs núko ‘six’ (Vellard 1967: 37), Puquina tacpa ‘five’ (Torero 2002: 454)). Among numerals above five, there are some cases of homonymy with Quechua/Aymara terms referring to specific entities, as for instance Lengua X tʃ͡ipana ‘nine’ and Quechua/Aymara tʃ͡ipana ‘fetter, bracelet’. In this talk, I will discuss two questions: (1) What is the origin of Lengua X numerals? (2) What do Lengua X numerals reveal about the linguistic past of the southern central Andes? References Ibarra Grasso, Dick. -

Work Papers of the Summer Intitute of Linguistics, 1993. University of North Dakota Session, Volume 37

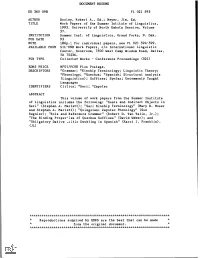

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 365 098 FL 021 593 AUTHOR Dooley, Robert A., Ed.; Meyer, Jim, Ed. TITLE Work Papers of the Summer Intitute of Linguistics, 1993. University of North Dakota Session, Volume 37. INSTITUTION Summer Inst. of Linguistics, Grand Forks, N. Dak. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 186p.; For individual papers, see FL 021 594-599. AVAILABLE FROM SIL-UND Work Papers, c/o International Linguistic Center, Bookroom, 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road, Dallas, TX 75236. PUB TYPE Collecteet Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Grammar; *Kinship Terminology; Linguistic Theory; *Phonology; *Quechua; *Spanish; Structural Analysis (Linguistics); Suffixes; Syntax; Uncommonly Taught Languages IDENTIFIERS Clitics; *Seri; *Zapotec ABSTRACT This volume of work papers from the Summer Institute of Linguistics includes the following: "Goals and Indirect Objects in Seri" (Stephen A. Marlett); "Seri Kinship Terminology" (Mary B. Moser and Stephen A. Marlett); "Quiegolani Zapotec Phonology" (Sue Regnier); "Role and Reference Grammar" (Robert D. Van Valin, Jr.); "The Binding Proper'ies of Quechua Suffixes" (David Weber); and "Obligatory Dative ,litic Doubling in Spanish" (Karol J. Franklin). (JL) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** WORK PAPERS VOLUME XXXVII 1993 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETHIS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN Office o4 Educabonal Research and Improvement GRANTED BY EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION Th,0\e_ CENTER (ERIC) Frftris document has been reproduced as recemed from the person or organization orrginatrng re 0 Minor changes have been made to rrnprom reproduction oualdy TO THE EDUCATIONAL Pornts of vrew or opmrons staled in this docu- RESOURCES ment do not necessarily represent official INFORMATION CENTER(ERIC).. -

On the External Relations of Purepecha: an Investigation Into Classification, Contact and Patterns of Word Formation Kate Bellamy

On the external relations of Purepecha: An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Kate Bellamy To cite this version: Kate Bellamy. On the external relations of Purepecha: An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation. Linguistics. Leiden University, 2018. English. tel-03280941 HAL Id: tel-03280941 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03280941 Submitted on 7 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/61624 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Bellamy, K.R. Title: On the external relations of Purepecha : an investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Issue Date: 2018-04-26 On the external relations of Purepecha An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation Published by LOT Telephone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht Email: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Kate Bellamy. ISBN: 978-94-6093-282-3 NUR 616 Copyright © 2018: Kate Bellamy. All rights reserved. On the external relations of Purepecha An investigation into classification, contact and patterns of word formation PROEFSCHRIFT te verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof.