The First Three Years of the Afro-American Studies Harvard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

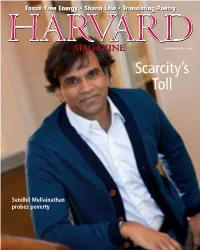

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin

Traut 1 Katerina Traut Lehigh University Giving ‘Substance to Freedom and Democracy’: Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin ABSTRACT: This paper explores labor organizer Vicki Garvin's life and ideas as an instantiation of Black feminism and as characterized by features central to contemporary Black feminist thought. Garvin's philosophy and practice of feminism come forth in her research and activism in worker’s rights, African American’s rights, and women’s rights. Garvin came of age in a post-WWII era of politics that was shaped by social movements toward liberation. As a demonstration of how to resist domination and oppression while remaining committed to the practice of democracy, Garvin's lifework deserves attention. INTRODUCTION According to Patricia Hill Collins, one distinguishing feature of Black feminist thought is that there is a dialectical relationship between oppression and activism, and there is a dialogical relationship between Black women's collective experiences of oppression and their group knowledge.1 Because of their unique position within the matrix of domination, defined as the social organization in which intersecting oppressions are developed, maintained, and maneuvered, African American women have a special knowledge about the interlocking nature of race, gender, and class oppression.2 Therefore, they must be a part of any effective effort to critique and overcome oppression. As Collins explains, this insight was known and practiced well before contemporary feminist thinkers such as herself conceptualized Black feminist thought as a particular field of scholarship. The research and activism of labor organizer Vicki Garvin demonstrates an understanding of the specific and important role that African American women (as one of many historically marginalized/oppressed groups) have to play within the Traut 2 institutional contexts that create and perpetuate their oppression. -

Pdf (Last Accessed February 13, 2015)

Notes Introduction 1. Perry A. Hall, In the Vineyard: Working in African American Studies (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1999), 17. 2. Naomi Schaefer Riley, “The Most Persuasive Case for Eliminating Black Studies? Just Read the Dissertations,” The Chronicle of Higher Education (April 30, 2012). http://chronicle.com/blogs/brainstorm/the-most-persuasive-case -for-eliminating-black-studies-just-read-the-dissertations/46346 (last accessed December 7, 2014). 3. William R. Jones, “The Legitimacy and Necessity of Black Philosophy: Some Preliminary Considerations,” The Philosophical Forum 9(2–3) (Winter–Spring 1977–1978), 149. 4. Ibid., 149. 5. Joseph Neff and Dan Kane, “UNC Scandal Ranks Among the Worst, Experts Say,” Raleigh News and Observer (Raleigh, NC) (October 25, 2014). http:// www.newsobserver.com/2014/10/25/4263755/unc-scandal-ranks-among -the-worst.html?sp=/99/102/110/112/973/. This is just one of many recent instances of “academic fraud” and sports that include Florida State University, University of Minnesota, University of Georgia and Purdue University. 6. Robert L. Allen, “Politics of the Attack on Black Studies,” in African American Studies Reader, ed. Nathaniel Norment (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2007), 594. 7. See Shawn Carrie, Isabelle Nastasia and StudentNation, “CUNY Dismantles Community Center, Students Fight Back,” The Nation (October 25, 2013). http://www.thenation.com/blog/176832/cuny-dismantles-community - center-students-fight-back# (last accessed February 17, 2014). Both Morales and Shakur were former CCNY students who became political exiles. Morales was involved with the Puerto Rican independence movement. He was one of the many students who organized the historic 1969 strike by 250 Black and Puerto Rican students at CCNY that forced CUNY to implement Open Admissions and establish Ethnic Studies departments and programs in all CUNY colleges. -

The Counterrevolution on Campus Why Was Black Studies So Controversial?

CHAPTER 6 The Counterrevolution on Campus Why Was Black Studies So Controversial? The incorporation of Black studies in American higher education was a major goal of the Black student movement, but as we have seen from San Francisco State College, City College of New York, Northwestern University, and many other campuses, the promise to implement it was typically followed by another period of struggle. Whether it was because of hostility, clashing visions, budget cuts, indifference, or other challenges, the effort to institutionalize Black studies was long and difficult. To the extent that there was a “black revolution on campus,” it was followed, in many instances, by a “counterrevolution,” a determined effort to contain the more ambitious desires of students and intellectuals. This chapter explores critical challenges and points of contention during the early Black studies movement, with a particular focus on events at Harvard University. The struggle at Harvard concerned issues common to virtually every effort to institutionalize Black studies, although not all were as contentious or politicized as in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the early 1970s. As St. Clair Drake dryly noted, “The 1968–73 period was a unique one in American academia.”1 This chapter also examines the controversy and conflicts surrounding the meaning and mission of Black studies. Black studies was controversial among many, both inside and outside academe, for its intellectual ideas, shaped as they were by the swirling ideological currents of Black nationalism. Black studies was seen by many as an academically suspect, antiwhite, emotional intrusion into a landscape of rigor and reason. But rather than a movement of narrow nationalism and anti-intellectualism, as some critics charged, the early Black studies movement advanced ideas that have had significant influence in American and African American intellectual life. -

The Way Forward: Educational Leadership and Strategic Capital By

The Way Forward: Educational Leadership and Strategic Capital by K. Page Boyer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education (Educational Leadership) at the University of Michigan-Dearborn 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bonnie M. Beyer, Chair LEO Lecturer II John Burl Artis Professor M. Robert Fraser Copyright 2016 by K. Page Boyer All Rights Reserved i Dedication To my family “To know that we know what we know, and to know that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge.” ~ Nicolaus Copernicus ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Bonnie M. Beyer, Chair of my dissertation committee, for her probity and guidance concerning theories of school administration and leadership, organizational theory and development, educational law, legal and regulatory issues in educational administration, and curriculum deliberation and development. Thank you to Dr. John Burl Artis for his deep knowledge, political sentience, and keen sense of humor concerning all facets of educational leadership. Thank you to Dr. M. Robert Fraser for his rigorous theoretical challenges and intellectual acuity concerning the history of Christianity and Christian Thought and how both pertain to teaching and learning in America’s colleges and universities today. I am indebted to Baker Library at Dartmouth College, Regenstein Library at The University of Chicago, the Widener and Houghton Libraries at Harvard University, and the Hatcher Graduate Library at the University of Michigan for their stewardship of inestimably valuable resources. Finally, I want to thank my family for their enduring faith, hope, and love, united with a formidable sense of humor, passion, optimism, and a prodigious ability to dream. -

From Prison to Homeless Shelter: Camp Laguardia and the Political Economy of an Urban Infrastructure

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 From Prison to Homeless Shelter: Camp LaGuardia and the Political Economy of an Urban Infrastructure Christian D. Siener The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2880 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] From Prison to Homeless Shelter Camp LaGuardia and the Political Economy of an Urban Infrastructure Christian D. Siener A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Earth and Environmental Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 Christian D. Siener All Rights Reserved ii From Prison to Homeless Shelter Camp LaGuardia and the Political Economy of an Urban Infrastructure by Christian D. Siener This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Earth and Environmental Sciences in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________ ______________________________ Date Ruth Wilson Gilmore Chair of Examining Committee _________________________ ______________________________ Date Cindi Katz Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Marianna Pavlovskaya Monica Varsanyi THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT From Prison to Homeless Shelter Camp LaGuardia and the Political Economy of an Urban Infrastructure Christian D. Siener Advisor: Ruth Wilson Gilmore At this time of increasing housing insecurity, recent reforms in homeless shelter policy have attracted the attention of scholars and activists. -

Japa Nese American Progressives

CHAPTER 14 Japa nese American Progressives A Case Study in Identity Formation Mari Matsuda Over ozoni on New Year’s Day of 2011, I told my 86- year- old father I was going to a conference to discuss racial identity of Japa nese Americans. “How do you think pe ople saw themselves?” I asked about the Issei Uchinanchu. “Did they think of themselves as Okinawan or just Japa nese?” He replied, “It depends, it depends who, where. Hawaiʻi? California? Southern California? It depends when. When did they come?” “It depends” is prob ably the answer to the question proposed in many chapters in this book, as questions about racial formation always intersect with par tic u lar circumstances in complicated ways. The particularity ex- plored in this chapter is Japa nese American progressive po liti cal identity, including its race and ethnicity aspects. “You know what they said about Okinawans in the old days . ,” a Nisei community leader said to me conspiratorially at a luncheon at the Oki- nawan Center. “Buta kau kau. Aka. That’s what they said about us.” The first phrase is an amalgam of Hawaiian and Nihongo, meaning, roughly, “they eat pig slop.” The second phrase is po liti cal. Even in Hawaiʻi, which in my father’s taxonomy was less progressive than Los Angeles, where he grew up, the taint of aka, red, Communist, is part of Okinawan identity. People whisper when they say it. As a Sansei progressive, I have always traced my po liti cal lineage to the great Issei working- class scholar activists I was privileged to know as a child. -

How New York Changes the Story of the Civil Rights Movement

How New York changes the story of the Civil Rights Movement By Martha Biondi When most people say "the civil rights movement" they are referring to the struggle against southern Jim Crow. They don't think to call it the southern civil rights movement because the southern-ness of the movement is taken for granted. But we actually should call it the southern civil rights movement, because there was a northern civil rights movement that needs to be recognized and understood on its own unique terms. The southern civil rights movement was preceded for over a decade by the northern civil rights movement. This northern civil rights movement had as its major center, New York City. The movement arose during the mass migration of Black southerners in the 1940s, which gave New York the largest urban black population in the world. The early civil rights movement in New York is the story of Jackie Robinson to Paul Robeson to Malcolm X, a trajectory from integrationist optimism to Black Nationalist critique, with a flourishing African American left at its center. Since this trajectory foreshadows what would happen nationally in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly the move from liberalism to Black Power, the early experience in New York has much to teach us about activism and resistance in the urban North. Yet despite this significance, the northern civil rights movement has been largely "forgotten," and omitted from the standard narrative of the U. S. Civil Rights Movement. (2) In this essay I will provide some examples of the multiple struggles of the New York civil rights movement, but my primary focus will be to explain why they matter, and to illustrate how the northern movement alters the larger portrait of the American Civil Rights Movement. -

Black Identities in US-Caribbean Encounters

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 32 Issue 2 Article 12 December 2014 Globalization's People: Black Identities in U.S.-Caribbean Encounters Hope Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Hope Lewis, Globalization's People: Black Identities in U.S.-Caribbean Encounters, 32(2) LAW & INEQ. 349 (2014). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol32/iss2/12 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. 349 Globalization's People: Black Identities in U.S.-Caribbean Encounters Hope Lewist Transnationalism has a significant, yet often under- recognized, impact on the complex racial identities of both Black migrant and native-born African-American communities throughout their colonial, independence, and post-colonial histories. This commentary discusses how the U.S. legal, political, economic, and cultural discourse on race is inextricably linked with, and shaped by, international and foreign understandings of racial identity. The essay "samples" illustrative historical and contemporary encounters among the people, politics, economics, and culture of Jamaica and other English-speaking Caribbean countries with U.S. racial politics to illustrate this point. Rejecting the need for recent popular debates about purported cultural or ethnic "superiority,"' it instead calls for continuing and enhanced cross-cultural dialogue and fertilization as we look to the future of civil rights and other rights-based movements. Native- born and transmigrant groups, including those of African descent, have always learned a great deal from each other and can continue t. Professor of Law and Faculty Director, Global Law Studies, Northeastern University School of Law. -

Department Conditions and the Emergence of New Disciplines: Two

Departmental conditions and the emergence of new disciplines: Two cases in the legitimation of African-American Studies MARIO L. SMALL Harvard University The issue One of the central concerns of the sociology of science and knowledge has been to understand how social, political, and institutional factors a¡ect the construction and de¢nition of scienti¢c knowledge. Recent literature in this ¢eld suggests that how scientists in disciplines such as sociology, economics, and psychology de¢ne the tasks, method, and subject matter of their disciplines is a¡ected by the institutional con- ditions of the early departments in which the disciplines emerged.1 Responding to analyses of the emergence of the American social sciences that over-emphasize the role of the growth of nation-wide intellectual communities, this literature has emphasized that the ``local'' conditions in key departments at several universities were equally im- portant in how these disciplines took shape.2 Thus, Camic3 argues that we cannot understand the emergence of three main approaches within modern sociology ^ inductive observation, statistical generalization, and analytical abstraction ^ without understanding the local condi- tions of the early sociology departments at, respectively, Chicago (Small and Park), Columbia (Giddings), and Harvard (Parsons). As a whole, this literature suggests, without disregarding the larger macro- social factors a¡ecting the development of new disciplines,4 that much of what a¡ects how newly emerging disciplines are de¢ned may be found in the early departments in which they emerged. In this article, I address three unexplored issues in this growing body of work. First, within the literature ^ which consists largely, and justi¢ably, of independent case studies ^ there has been little e¡ort to develop systematic frameworks from which to understand how these local conditions a¡ect the intellectual development of new disciplines. -

The Black Campus Movement

THE BLACK CAMPUS MOVEMENT: AN AFROCENTRIC NARRATIVE HISTORY OF THE STRUGGLE TO DIVERSIFY HIGHER EDUCATION, 1965-1972 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Ibram Henry Rogers Department of African American Studies November 2009 i © Ibram Henry Rogers 2009 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT THE BLACK CAMPUS MOVEMENT: AN AFROCENTRIC NARRATIVE HISTORY OF THE STRUGGLE TO DIVERSIFY HIGHER EDUCATION, 1965-1972 Ibram Henry Rogers Temple University, 2009 Doctor of Philosophy Major Adviser: Dr. Ama Mazama In 1965, Blacks were only about 4.5 percent of the total enrollment in American higher education. College programs and offices geared to Black students were rare. There were few courses on Black people, even at Black colleges. There was not a single African American Studies center, institute, program, or department on a college campus. Literature on Black people and non-racist scholarly examinations struggled to stay on the margins of the academy. Eight years later in 1973, the percentage of Blacks students stood at 7.3 percent and the absolute number of Black students approached 800,000, almost quadrupling the number in 1965. In 1973, more than 1,000 colleges had adopted more open admission policies or crafted particular adjustments to admit Blacks. Sections of the libraries on Black history and culture had dramatically grown and moved from relative obscurity. Nearly one thousand colleges had organized Black Studies courses, programs, or departments, had a tutoring program for Black students, were providing diversity training for workers, and were actively recruiting Black professors and staff. -

Fifty Years of African and African American Studies at Harvard, 1969

Fifty Years of African and African American Studies at Harvard 1969–2019 COPYRIGHT © 2021 BY THE PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE Compiled, edited, and typeset by the Class Report Office, Harvard Alumni Association Contents Foreword ............................................................................................... v A Special Congratulations from Neil Rudenstine ...........................xiii Department of African and African American Studies .....................xiv Greeting from the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences ............ 1 Reflections of the Former Department Chairs .................................. 3 Werner Sollors ................................................................................. 3 Henry Louis Gates Jr. ........................................................................ 7 Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham ..........................................................11 Lawrence D. Bobo .............................................................................15 Reflections of the Faculty .................................................................21 Emmanuel K. Akyeampong ................................................................21 Jacob Olupona ..................................................................................25 Kay Kaufman Shelemay .....................................................................27 Jesse McCarthy .................................................................................28 Brandon Terry ..................................................................................29