Japa Nese American Progressives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05v6t6rn Author Kameyama, Eri Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Asian American Studies By Eri Kameyama 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations By Eri Kameyama Master of Arts in Asian American Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, Chair ABSTRACT: The recent census shows that one-third of those who identified as Japanese-American in California were foreign-born, signaling a new-wave of immigration from Japan that is changing the composition of contemporary Japanese-America. However, there is little or no academic research in English that addresses this new immigrant population, known as Shin-Issei. This paper investigates how Shin-Issei who live their lives in a complex space between the two nation-states of Japan and the U.S. negotiate their ethnic identity by looking at how these newcomers find a sense of belonging in Southern California in racial, social, and legal terms. Through an ethnographic approach of in-depth interviews and participant observation with six individuals, this case-study expands the available literature on transnationalism by exploring how Shin-Issei negotiations of identities rely on a transnational understandings of national ideologies of belonging which is a less direct form of transnationalism and is a more psychological, symbolic, and emotional reconciliation of self, encompassed between two worlds. -

AACP BOARD of DIRECTORS Florence M. Hongo, President Kathy Reyes, Vice President Rosie Shimonishi, Secretary Don Sekimura, Treasurer Leonard D

AACP BOARD OF DIRECTORS Florence M. Hongo, President Kathy Reyes, Vice President Rosie Shimonishi, Secretary Don Sekimura, Treasurer Leonard D. Chan Sutapa Dah Joe Chung Fong, PhD. Michele M. Kageura Susan Tanioka Sylvia Yeh Shizue Yoshina HONORARY BOARD Jerry Hiura Miyo Kirita Sadao Kinoshita Astor Mizuhara, In Memoriam Shirley Shimada Stella Takahashi Edison Uno, In Memoriam Hisako Yamauchi AACP OFFICE STAFF Florence M. Hongo, General Manager Mas Hongo, Business Manager Leonard D. Chan, Internet Consultant AACP VOLUNTEERS Beverly A. Ang, San Jose Philip Chin, Daly City Kiyo Kaneko, Sunnyvale Michael W. Kawamoto, San Jose Peter Tanioka, Merced Paul Yoshiwara, San Mateo Jaime Young AACP WELCOMES YOUR VOLUNTEER EFFORTS AACP has been in non-profit service for over 32 years. If you are interested in becoming an AACP volunteer, call us at (650) 357-1008 or (800) 874-2242. OUR MISSION To educate the public about the Asian American experience, fostering cultural awareness and to educate Asian Americans about their own heritage, instilling a sense of pride. CREDITS Typesetting and Layout – Sue Yoshiwara Editor– Florence M. Hongo/ Sylvia Yeh Cover – F.M. Hongo/L. D. Chan TABLE OF CONTENTS GREETINGS TO OUR SUPPORTERS i ELEMENTARY (Preschool through Grade 4) Literature 1-6 Folktales 7-11 Bilingual 12-14 ACTIVITIES (All ages) 15-19 Custom T-shirts 19 INTERMEDIATE (Grades 5 through 8) Educational Materials 20-21 Literature 22-26 Anti-Nuclear 25-26 LITERATURE (High School and Adult) Anthologies 27-28 Cambodian American 28 Chinese American 28-32 Filipino -

The Politics of Transnational History Making: Japanese Immigrants on T

Eiichiro Azuma | The Politics of Transnational History Making: Japanese Immigrants on t... Page 1 of 28 http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jah/89.4/azuma.html From The Journal of American History Vol. 89, Issue 4. Viewed December 3, 2003 15:52 EST Presented online in association with the History Cooperative. http://www.historycooperative.org The Politics of Transnational History Making: Japanese Immigrants on the Western 'Frontier,' 1927-1941 Eiichiro Azuma In 1927 Toga Yoichi, a Japanese immigrant in Oakland, California, published a chronological 1 history of what he characterized as 'Japanese development in America.' He explicated the meaning of that history thus: A great nation/race [minzoku] has a [proper] historical background; a nation/race disrespectful of history is doomed to self-destruction. It has been already 70 years since we, the Japanese, marked the first step on American soil. Now Issei [Japanese immigrants] are advancing in years, and the Nisei [the American- born Japanese] era is coming. I believe that it is worthy of having [the second generation] inherit the record of our [immigrant] struggle against oppression and hardships, despite which we have raised our children well and reached the point at which we are now. But, alas, we have very few treatises of our history [to leave behind]. Thirteen years later, a thirteen hundred-page masterpiece entitled Zaibei Nihonjinshi--Toga himself spearheaded the editing--completed that project of history writing.1 Not the work of trained academicians, this synthesis represented the collaboration of many Japanese immigrants, including the self-proclaimed historians who authored it, community leaders who provided subventions, and ordinary Issei residents who offered necessary information or purchased the product. -

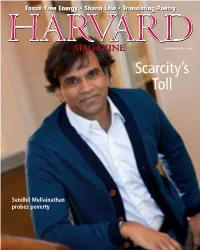

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

Before Pearl Harbor 29

Part I Niseiand lssei Before PearlHarbor On Decemb er'7, 194L, Japan attacked and crippled the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. Ten weeks later, on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 under which the War De- partment excluded from the West Coast everyone of Japanese ances- try-both American citizens and their alien parents who, despite long residence in the United States, were barred by federal law from be- coming American citizens. Driven from their homes and farms and "relocation businesses, very few had any choice but to go to centers"- Spartan, barrack-like camps in the inhospitable deserts and mountains of the interior. * *There is a continuing controversy over the contention that the camps "concentration were camps" and that any other term is a euphemism. The "concentration government documents of the time frequently use the term camps," but after World War II, with full realization of the atrocities committed by the Nazis in the death camps of Europe, that phrase came to have a very different meaning. The American relocation centers were bleak and bare, and life in them had many hardships, but they were not extermination camps, nor did the American government embrace a policy of torture or liquidation of the "concentration To use the phrase camps summons up images ethnic Japanese. "relo- ,and ideas which are inaccurate and unfair. The Commission has used "relocation cation centers" and camps," the usual term used during the war, not to gloss over the hardships of the camps, but in an effort to {ind an historically fair and accurate phrase. -

Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin

Traut 1 Katerina Traut Lehigh University Giving ‘Substance to Freedom and Democracy’: Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin ABSTRACT: This paper explores labor organizer Vicki Garvin's life and ideas as an instantiation of Black feminism and as characterized by features central to contemporary Black feminist thought. Garvin's philosophy and practice of feminism come forth in her research and activism in worker’s rights, African American’s rights, and women’s rights. Garvin came of age in a post-WWII era of politics that was shaped by social movements toward liberation. As a demonstration of how to resist domination and oppression while remaining committed to the practice of democracy, Garvin's lifework deserves attention. INTRODUCTION According to Patricia Hill Collins, one distinguishing feature of Black feminist thought is that there is a dialectical relationship between oppression and activism, and there is a dialogical relationship between Black women's collective experiences of oppression and their group knowledge.1 Because of their unique position within the matrix of domination, defined as the social organization in which intersecting oppressions are developed, maintained, and maneuvered, African American women have a special knowledge about the interlocking nature of race, gender, and class oppression.2 Therefore, they must be a part of any effective effort to critique and overcome oppression. As Collins explains, this insight was known and practiced well before contemporary feminist thinkers such as herself conceptualized Black feminist thought as a particular field of scholarship. The research and activism of labor organizer Vicki Garvin demonstrates an understanding of the specific and important role that African American women (as one of many historically marginalized/oppressed groups) have to play within the Traut 2 institutional contexts that create and perpetuate their oppression. -

Japanese Musical Performance and Diaspora

Japanese Musical Performance and Diaspora Andrew N. Weintraub Contract laborers from Japan were brought to Hawai'i in large numbers beginning in 1885. The first generation of Japanese immigrants, or issei, were primarily farmers, fishermen, and country folk. By 1920, forty percent of the population in Hawai'i was Japanese. Issei immigrants paved the way for their children (nisei, or second generation), grandchildren (sansei, or third generation), and great-grandchildren (yonsei, or fourth generation). The Japanese impact on local Hawaiian culture can be seen in many areas, including foods, customs, architecture, and public music and dance festivals. Bon odori (or bon dance) in Hawai'i has endured many changes since the first group of issei arrived on the islands. During the plantation period (1880s to 1910s), the immigrants steadfastly kept the tradition alive despite low working wages, difficult living conditions, and isolation from their homeland. In the 1930s, with the new homeland established, the tradition was strengthened by new choreographies, new music, contests, and scheduled dances. During this time the bon dance became a popular social event that appealed particularly to the younger generation. After the outbreak of World War II in December 1941, priests were detained, temples were closed, and Japanese were discouraged from gathering in large numbers. It became dangerous for Japanese to make any public expressions of national pride. Bon dance activities probably did not take place again until after the war ended in 1945. But during the 1950s and 1960s, a revival of bon odori took place. In addition to temple festivals, bon dances were sponsored by groups outside the temples for non-religious functions. -

Pdf (Last Accessed February 13, 2015)

Notes Introduction 1. Perry A. Hall, In the Vineyard: Working in African American Studies (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1999), 17. 2. Naomi Schaefer Riley, “The Most Persuasive Case for Eliminating Black Studies? Just Read the Dissertations,” The Chronicle of Higher Education (April 30, 2012). http://chronicle.com/blogs/brainstorm/the-most-persuasive-case -for-eliminating-black-studies-just-read-the-dissertations/46346 (last accessed December 7, 2014). 3. William R. Jones, “The Legitimacy and Necessity of Black Philosophy: Some Preliminary Considerations,” The Philosophical Forum 9(2–3) (Winter–Spring 1977–1978), 149. 4. Ibid., 149. 5. Joseph Neff and Dan Kane, “UNC Scandal Ranks Among the Worst, Experts Say,” Raleigh News and Observer (Raleigh, NC) (October 25, 2014). http:// www.newsobserver.com/2014/10/25/4263755/unc-scandal-ranks-among -the-worst.html?sp=/99/102/110/112/973/. This is just one of many recent instances of “academic fraud” and sports that include Florida State University, University of Minnesota, University of Georgia and Purdue University. 6. Robert L. Allen, “Politics of the Attack on Black Studies,” in African American Studies Reader, ed. Nathaniel Norment (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2007), 594. 7. See Shawn Carrie, Isabelle Nastasia and StudentNation, “CUNY Dismantles Community Center, Students Fight Back,” The Nation (October 25, 2013). http://www.thenation.com/blog/176832/cuny-dismantles-community - center-students-fight-back# (last accessed February 17, 2014). Both Morales and Shakur were former CCNY students who became political exiles. Morales was involved with the Puerto Rican independence movement. He was one of the many students who organized the historic 1969 strike by 250 Black and Puerto Rican students at CCNY that forced CUNY to implement Open Admissions and establish Ethnic Studies departments and programs in all CUNY colleges. -

Folklife Bibliography by Joanne B

Folklife Bibliography By Joanne B. Mulcahy Aarne, Anti, and Stith Thompson. The Types of the Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communication No. 180. Helsinki, Finland: Academic Scientarum Fennica, 1960. Azuma, Eichiro. “A History of Oregon’s Issei, 1880–1952.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 94 (1993-94): 315–67. Barber, Katrine. “Stories Worth Recording: Martha McKeown and the Documentation of Pacific Northwest Life.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 110:4 (Winter 2009): 546-569. Beck, David R.M. “’Standing out Here in the Surf’: The Termination and Restoration of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians of Western Oregon in Historical Perspective.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 110:1 (Spring 2009): 6-37. Beckham, Steven Dow. Tall Tales from Rogue River: The Yarns of Hathaway Jones. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1974. Reprint, Oregon State University Press, 1991. _____. The Indians of Western Oregon: This Land Was Theirs. Coos Bay, OR: Arago Books, 1977. Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Translator.” In Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1969. Berg, Laura, ed. The First Oregonians. Portland: Oregon Council for the Humanities, 2007. Browner, Tara. Heartbeat of the People: Music and Dance of the Northern Pow-Wow. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002. Brunvand, Jan Harold. The Vanishing Hitchhiker: Urban Legends and Their Meanings. New York: W.W. Norton, 1981. Buan, Carolyn M., and Richard Lewis. The First Oregonians: An Illustrated Collection of Essays on Traditional Lifeways, Federal-Indian Relations, and the State’s Native People Today. Portland: Oregon Council for the Humanities, 1991. Cannon, Hal, ed. New Cowboy Poetry: A Contemporary Gathering. Layton, UT: Peregrine Smith Books, 1990. -

From Japonés to Nikkei: the Evolving Identities of Peruvians of Japanese

From japonés to Nikkei: The Evolving Identities of Peruvians of Japanese Descent by Eszter Rácz Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Professor Szabolcs Pogonyi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2019 Abstract This thesis investigates what defines the identity of third- and fourth-generation Japanese Peruvians and what is the current definition of Nikkei ethnic belonging on personal as well as institutional level. I look at the identity formation processes of Peruvians with ethnic Japanese background in light of the strong attachment to Japan as an imagined homeland, the troubled history of anti-Japanese discrimination in Peru and US internment of Japanese Peruvians during World War II, the consolidation of Japanese as a high-status minority, and ethnic return migration to Japan from 1990. Ethnicity has been assumed to be the cornerstone of identity in both Latin America where high sensitivity for racial differences results in intergenerational categorization and Japan where the essence of Japaneseness is assumed to run through one’s veins and passed on to further generations even if they were born and raised abroad. However when ethnic returnees arrived to Japan they had to realize that they were not Japanese by Japanese standards and chose to redefine themselves, in the case of Japanese Peruvians as Nikkei. I aim to explore the contents of the Japanese Peruvian definition of Nikkei by looking at existing literature and conducting video interviews through Skype and Messenger with third- and fourth-generation Japanese Peruvians. I look into what are their personal experiences as Nikkei, what changes do they recognize as the consequence of ethnic return migration, whether ethnicity has remained the most relevant in forming social relations, and what do they think about Japan now that return migration is virtually ended and the visa that allowed preferential access to Japanese descendants is not likely to be extended to further generations. -

Japanese Americans in the Pacific Before World War II

A Transnational Generation: Japanese Americans in the Pacific before World War II Michael JIN By the eve of the Second World War, thousands of second-generation Japanese Americans (Nisei) had lived and traveled outside the United States. Most of them had been sent to Japan at young ages by their first-generation (Issei) parents to be raised in the households of their relatives and receive proper Japanese education. Others were there on short-term tours sponsored by various Japanese organizations in the U.S. to experience the culture and society of their parents’ homeland. Many also sought opportunities for employment or higher education in a country that represented an expanding colonial power especially during the 1930s. Although no official data exists to help determine the exact number of Nisei in Japan before the Pacific War, various sources suggest that about 50,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry spent some of their formative years in Japan. Of these Nisei, 10,000-20,000 returned to the United States before the outbreak of Pearl Harbor and became known as Kibei (literally, “returned to America”). 1) The Nisei who migrated to Japan at young ages and those who embarked on subsequent journeys to Japan’s colonial world in the Pacific rarely appear in the popular narratives of Japanese American history. The U.S.-centered immigrant paradigm has confined the history of Nisei to the interior of U.S. political and cultural boundaries. Moreover, the Japanese American internment during World War II and the emphasis on Nisei loyalty and nationalism have been dominant themes in the postwar scholarship and public history of Japanese Americans. -

CONGRATULATIONS to the CLASS of 2020 Continue to Pursue Your Dreams from the Greater Seattle Awards Committee

VOLUME 28 FALL 2020 CONGRATULATIONS TO THE CLASS OF 2020 Continue to Pursue Your Dreams From the Greater Seattle Awards Committee We were so excited NSRCF decided that we personally to return to the Greater Seattle area contributed for its 40th anniversary. The local and raised awards committee is a passionate approximately and thoughtful group, comprised of $15,000 from the community and education leaders local community. who genuinely care about helping We also students gain access to higher dedicated education. Many of us were also $5,000 of the first-generation college students and locally raised we chose to serve on this committee funds to provide because of the huge opportunity for scholarships to Black Lives Matter us to give back and pay it forward. four Pacific Islander students. The Seattle Awards Committee would like to take a moment to Southeast Asian students are faced Thank you to the families, teachers, reflect on the racial injustices that are with barriers and challenges around and advisors who worked tirelessly happening in our nation amidst this language, gaps in mental health to support them. Thank you, pandemic. We as Asian Americans treatment, race-based bullying, students, for sharing your stories, and Pacific Islanders stand in and harassment that prevent hardships, and goals with us. It was solidarity with the Black Community many of them from obtaining inspiring tolearn how much you have and condemn the violence they face. higher education. To that end, we overcome, how you rise above the While the struggle for racial equality worked hard to ensure an inclusive, noise to reach your goals, and the and justice is ongoing, the turbulence accessible process, including ways you give back to your families of the past months must not providing workshops and tools to and communities.