The Way Forward: Educational Leadership and Strategic Capital By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Timeline of Women at Yale Helen Robertson Gage Becomes the first Woman to Graduate with a Master’S Degree in Public Health

1905 Florence Bingham Kinne in the Pathology Department, becomes the first female instructor at Yale. 1910 First Honorary Degree awarded to a woman, Jane Addams, the developer of the settlement house movement in America and head of Chicago’s Hull House. 1916 Women are admitted to the Yale School of Medicine. Four years later, Louise Whitman Farnam receives the first medical degree awarded to a woman: she graduates with honors, wins the prize for the highest rank in examinations, and is selected as YSM commencement speaker. 1919 A Timeline of Women at Yale Helen Robertson Gage becomes the first woman to graduate with a Master’s degree in Public Health. SEPTEMBER 1773 1920 At graduation, Nathan Hale wins the “forensic debate” Women are first hired in the college dining halls. on the subject of “Whether the Education of Daughters be not without any just reason, more neglected than that Catherine Turner Bryce, in Elementary Education, of Sons.” One of his classmates wrote that “Hale was becomes the first woman Assistant Professor. triumphant. He was the champion of the daughters and 1923 most ably advocated their cause.” The Yale School of Nursing is established under Dean DECEMBER 1783 Annie Goodrich, the first female dean at Yale. The School Lucinda Foote, age twelve, is interviewed by Yale of Nursing remains all female until at least 1955, the President Ezra Stiles who writes later in his diary: earliest date at which a man is recorded receiving a degree “Were it not for her sex, she would be considered fit to at the school. -

Bradley Pt1.Pdf

Please Note This oral history transcript has been divided into multiple parts. The first part documents the presidency of John G. Kemeny and is open to the public. The second part documents the presidency of David T. McLaughlin and will be open to the public in June 2012. The third and final part documents the presidency of James O. Freedman and will be open to the public in June 2023. This is part one. Edward Bradley Interview Edward M. Bradley Professor of Classics, Emeritus An interview conducted by Mary S. Donin February 12, and 24, 2009 Hanover, NH Rauner Special Collections Library Dartmouth College Hanover, NH 2 Edward Bradley Interview INTERVIEWEE: Edward M. Bradley INTERVIEWER: Mary S. Donin DATE: February 12 and 24, 2009 PLACE: Hanover, NH DONIN: All right, so today is Thursday, February 12, 2009. My name is Mary Donin and we are in Rauner Library with Edward M. Bradley—Professor Edward M. Bradley. Professor emeritus, I guess I should say. That was as of 2006 that you became emeritus? BRADLEY: 2006. Yes. DONIN: I guess weʼd like to start out, Professor Bradley, hearing about how it is you ended up coming to Dartmouth back in—I think it was 1963? BRADLEY: Yes. DONIN: Did you find Dartmouth or did Dartmouth find you? BRADLEY: Dartmouth found me. Dartmouth found me initially, I think, at the annual meeting of the Classical Association of New England in Lakeville, Connecticut. This must have been in the spring of 1962, where I met Norman [A.] Doenges and I was at that time working on my doctoral thesis and trying to find gainful employment. -

Elmhurst College Bluejays University of Chicago Maroons Elmhurst College Volleyball Quad

Elmhurst College Volleyball Quad October 12, 2019 - R.A. Faganel Hall 10:00 am - Chicago vs. North Central 12:00 pm - Chicago vs. Elmhurst 2:00 pm - UW-Eau Claire vs. North Central 4:00 pm - UW-Eau Claire vs. Elmhurst Elmhurst College Bluejays No. Name Pos. Ht. Yr. Hometown/Last School 2 Alexandra Tyggum OH 5-10 Jr. Guatemala City, Guatemala/American School of Guatemala 3 Taylor Zurliene OH 5-8 Jr. Shorewood, Ill./Joliet Catholic About Elmhurst 5 Bailey Brouwer RSH 5-10 Sr. Elkhart, Ind./Elkhart Memorial 7 Ellie Burzlaff RSH 5-9 Sr. Elgin, Ill./Harvest Christian Location .......................................Elmhurst, Ill. 8 Emily Duis MH 5-9 So. Sheldon, Ill./Milford Conference ............................................... CCIW 9 Sabrina Yamashita S/DS 5-5 Fr. Evansville, Ind./Reitz Memorial Current 2019 Season Record .................7-12 10 Payton Froats MH 5-10 Jr. Darien, Ill./Downers Grove South Final 2018 Season Record ....................12-19 11 Stacie Harms DS 5-8 Sr. Bloomington, Ill./Normal Community Current AVCA National Ranking ................N/A 12 Cyle Harrison MH/OH 5-11 Sr. Flossmoor, Ill./Homewood-Flossmoor 13 Hannah Horn S 5-8 Fr. Defiance, Ohio/Tinora 15 Emily Finkbeiner DS 5-4 So. Saline, Mich./H.S. 16 Katie Brown OH 5-9 So. St. Louis, Mo./Lutheran High School 17 Kayla Mast OH 5-10 So. Quincy, Ill./H.S. 19 Valerie Thomas DS 5-5 So. Mount Prospect, Ill./Prospect 20 Erin Murray S 5-8 Fr. Savage, Minn./Burnsville 21 Jadyn Ginther OH 5-10 Fr. Elmwood, Ill./H.S. 22 Brooklyn Gravel OH/RSH 5-9 Fr. -

Handbook Replaces All Previous Editions and Is the Document of Record When Referencing the Operating Principles of the Arts & Sciences

Ƭ November2018 DARTMOUTHCOLLEGE HANOVER,NEWHAMPSHIRE FOREWORD Dear Colleagues: This electronic edition of the Faculty Handbook replaces all previous editions and is the document of record when referencing the operating principles of the Arts & Sciences. The purpose of this document is to provide all of us with a common source for understanding the various policies and procedures of the Arts & Sciences, to provide convenient access to the guidelines of other areas of the College, to aid in the identification of available College resources, and to describe our basic organizational structure. Because of the range of topics covered in the Faculty Handbook, the source and authority for each varies. Some matters described in this document are the result of formal actions by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences or by one of its committees; others represent actions taken by the Board of Trustees; still others are the result of administrative practice and policy, either here in the Dean of the Faculty Office or other administrative areas. Some topics are covered primarily through links to online information in other areas of the College. The electronic format of this document will continue to permit modification and clarification of our policies. You should consult it often when referencing Arts & Sciences policy to ensure you have the latest version. While every effort has been made to make this Handbook as up to date as possible, changes will undoubtedly occur. Various committees and officers of the College having responsibility for areas covered by the Handbook reserve the right to make such changes in the policies and procedures contained in this Handbook as deemed appropriate. -

Cr·I·.+" ·T , · -'9E ;

-1 - - ID~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~'~. M s , a 9 f X A~.~~ + z t . >, ;s i~~~~`"" ,c ,N Ad e wDiMS~- A DC E r an ~~~~~~~~~~- r ; - . - > 4- r<t> i+i; -->><N ,&' _~ t* Ad vot e e * t-+x1 *_js Laeakf ~rs a~ IJW 4g s Adz *+se , -oU ,,.5 ^4' e B .;M I lt· ,`r * ,L I-t;-7: t- 46-''. ·": ` *t ". *I r··j· d. ·k : I--"* F-SP -4wmp- r m -'c :;l··s-.. : P- aT xf ;er, 11·-Pr ;3;"Al· At T'l '.1.' *IT,*Y 4b - - .I ' I gl*C·Crrr-·WIY(LIC·Bg·41YX·srYI·s-L· 'mo6 -- ~iosafss -"' - , ,- l-, .a n. >>r, J O _ ;s 9 , $ S a~~ Z *v ~~-11 Mr.-,sM -cls ranci;sj· j;::,,,·,., -.-*u--C·gr 19u?r- '----· ;r;ri· T·C;·",- -,-", r-, -- " -.- -.,I - .--11-1-11--.1-1- - "M tPt 1-. ,i 1,:t:t:i.. -,, , .·cr·i·.+" ·t , · -'9e ; .It, i ,:·P`f:ii·t ;·t '· * :·`t·X Imp-i __7Fa.. .J-i4 )I Page 2 The Tech Centennial Issue November 16 1881 Canrt see future a * 0 Students and Friends: GREETING. more, correcting the Junior, and To-day is issued the first num- supporting the Senior in his old z ber of our paper; and, although age. It will open an avenue for the we tremble at the thought of the expression of public opinion, and OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 9 work before us, we begin it gladly. will aim, in every possible way, to m We believe that the same public help all in their development of spirit that founded THE TECH their young manhood and young will sustain it to the end. -

The Law Rentian

« „ ♦ »/ I I V i C T O R i C LlDRÁrTh e La w r e n t ia n 01. 54. No. 2. LAWRENCE COLLEGE, APPLETON, WIS. Friday, October 2, 1936 >ne Hundred Moore Will Direct Brinckley Will Pep Band; Practice Play at Initial Schalk, Bartella [Seventy-Five Thursdays at 4:30 The pep band, which in recent All College Dance years has provoked considerable Head Committees Are Pledgedcriticism for its inefficiency, will be Annual Climax to Freeh- run under a new system this year. Sixteen Students Re »rorities Gain Ninety* Mr. E. C. Moore, director of the nian-Sophomore Battle The Lawrence Woineus College concert band, will diiect ceive All College One; Fraternities* Conies on October 10 Association Stricter both the concert and pep bands this Club Positions Eighty-Four year. The Tuesday afternoon re Now that the sophomores have Beware, all breakers of L. W. A. hearsal will be devoted to concert rules! Plans were made for stricter work, and the Thursday rehearsal, pretty well healed their wounded CHOSEN BY ARTHUR IVETAS LEAD CREEKS to pep band. Any who are interestpride, and the frosh have nearly enforcement of rules at a meeting ed in belonging to the latter organforgotten their overwhelming vic of the Judicial Board on Tuesday At the first executive Council inety Lawrence college co-eds ization may report at the Conserva tory, the occasion will be complet afternoon. Miss Woodworth, deanmeeting of the year Student Presi tory at 4:30 p. m. Thursday. eluding 24 from Appleton were ed with a bit of rhythm a week of women, addressed the board,dent Robert Arthur, appointed six edged to the six social sororities' from Saturday night, October 10, at urging them to carry out all the teen carefully selected students to the campus at ceremonies Sun- Seven Hundred the new Club Alexander. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Economic Report of the President.” ______

REFERENCES Chapter 1 American Civil Liberties Union. 2013. “The War on Marijuana in Black and White.” Accessed January 31, 2016. Aizer, Anna, Shari Eli, Joseph P. Ferrie, and Adriana Lleras-Muney. 2014. “The Long Term Impact of Cash Transfers to Poor Families.” NBER Working Paper 20103. Autor, David. 2010. “The Polarization of Job Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market.” Center for American Progress, the Hamilton Project. Bakija, Jon, Adam Cole and Bradley T. Heim. 2010. “Jobs and Income Growth of Top Earners and the Causes of Changing Income Inequality: Evidence from U.S. Tax Return Data.” Department of Economics Working Paper 2010–24. Williams College. Boskin, Michael J. 1972. “Unions and Relative Real Wages.” The American Economic Review 62(3): 466-472. Bricker, Jesse, Lisa J. Dettling, Alice Henriques, Joanne W. Hsu, Kevin B. Moore, John Sabelhaus, Jeffrey Thompson, and Richard A. Windle. 2014. “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2010 to 2013: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Federal Reserve Bulletin, Vol. 100, No. 4. Brown, David W., Amanda E. Kowalski, and Ithai Z. Lurie. 2015. “Medicaid as an Investment in Children: What is the Long-term Impact on Tax Receipts?” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 20835. Card, David, Thomas Lemieux, and W. Craig Riddell. 2004. “Unions and Wage Inequality.” Journal of Labor Research, 25(4): 519-559. 331 Carson, Ann. 2015. “Prisoners in 2014.” Bureau of Justice Statistics, Depart- ment of Justice. Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, Emmanuel Saez, and Nich- olas Turner. 2014. “Is the United States Still a Land of Opportunity? Recent Trends in Intergenerational Mobility.” NBER Working Paper 19844. -

Sherman Kent, Scientific Hubris, and the CIA's Office of National Estimates

Inman Award Essay Beacon and Warning: Sherman Kent, Scientific Hubris, and the CIA’s Office of National Estimates J. Peter Scoblic Beacon and Warning: Sherman Kent, Scientific Hubris, and the CIA’s Office of National Estimates Would-be forecasters have increasingly extolled the predictive potential of Big Data and artificial intelligence. This essay reviews the career of Sherman Kent, the Yale historian who directed the CIA’s Office of National Estimates from 1952 to 1967, with an eye toward evaluating this enthusiasm. Charged with anticipating threats to U.S. national security, Kent believed, as did much of the postwar academy, that contemporary developments in the social sciences enabled scholars to forecast human behavior with far greater accuracy than before. The predictive record of the Office of National Estimates was, however, decidedly mixed. Kent’s methodological rigor enabled him to professionalize U.S. intelligence analysis, making him a model in today’s “post- truth” climate, but his failures offer a cautionary tale for those who insist that technology will soon reveal the future. I believe it is fair to say that, as a on European civilization.2 Kent had no military, group, [19th-century historians] thought diplomatic, or intelligence background — in fact, their knowledge of the past gave them a no government experience of any kind. This would prophetic vision of what was to come.1 seem to make him an odd candidate to serve –Sherman Kent William “Wild Bill” Donovan, a man of intimidating martial accomplishment, whom President Franklin t is no small irony that the man who did D. -

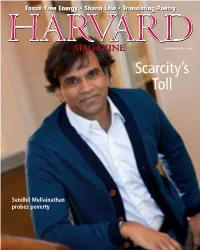

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

A Descriptive and Exploratory Case Study of the Evolution of Intercollegiate Athletics and Education at Loyola University Chicago: 1922-1994

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1996 A Descriptive and Exploratory Case Study of the Evolution of Intercollegiate Athletics and Education at Loyola University Chicago: 1922-1994 Thomas G. Hitcho Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Hitcho, Thomas G., "A Descriptive and Exploratory Case Study of the Evolution of Intercollegiate Athletics and Education at Loyola University Chicago: 1922-1994" (1996). Dissertations. 3622. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3622 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1996 Thomas G. Hitcho LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO A DESCRIPTIVE AND EXPLORATORY CASE STUDY OF THE EVOLUTION OF INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS AND EDUCATION AT LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO: 1922-1994 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP AND POLICY STUDIES BY THOMAS G. HITCHO DIRECTOR: STEVEN I. MILLER, PH.D. CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY, 1996 Copyright by Thomas G. Hitcho, 1996 All Rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is conceptualized from an organizational dimension within a sociological perspective. It is a focus on the study of the roles which intercollegiate athletics plays, intramurally and extramurally, of one sectarian sponsored university in the American Midwest over the past six decades. -

Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin

Traut 1 Katerina Traut Lehigh University Giving ‘Substance to Freedom and Democracy’: Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin ABSTRACT: This paper explores labor organizer Vicki Garvin's life and ideas as an instantiation of Black feminism and as characterized by features central to contemporary Black feminist thought. Garvin's philosophy and practice of feminism come forth in her research and activism in worker’s rights, African American’s rights, and women’s rights. Garvin came of age in a post-WWII era of politics that was shaped by social movements toward liberation. As a demonstration of how to resist domination and oppression while remaining committed to the practice of democracy, Garvin's lifework deserves attention. INTRODUCTION According to Patricia Hill Collins, one distinguishing feature of Black feminist thought is that there is a dialectical relationship between oppression and activism, and there is a dialogical relationship between Black women's collective experiences of oppression and their group knowledge.1 Because of their unique position within the matrix of domination, defined as the social organization in which intersecting oppressions are developed, maintained, and maneuvered, African American women have a special knowledge about the interlocking nature of race, gender, and class oppression.2 Therefore, they must be a part of any effective effort to critique and overcome oppression. As Collins explains, this insight was known and practiced well before contemporary feminist thinkers such as herself conceptualized Black feminist thought as a particular field of scholarship. The research and activism of labor organizer Vicki Garvin demonstrates an understanding of the specific and important role that African American women (as one of many historically marginalized/oppressed groups) have to play within the Traut 2 institutional contexts that create and perpetuate their oppression.