Japanese Musical Performance and Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

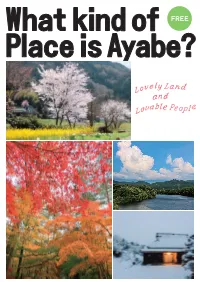

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05v6t6rn Author Kameyama, Eri Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Asian American Studies By Eri Kameyama 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations By Eri Kameyama Master of Arts in Asian American Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, Chair ABSTRACT: The recent census shows that one-third of those who identified as Japanese-American in California were foreign-born, signaling a new-wave of immigration from Japan that is changing the composition of contemporary Japanese-America. However, there is little or no academic research in English that addresses this new immigrant population, known as Shin-Issei. This paper investigates how Shin-Issei who live their lives in a complex space between the two nation-states of Japan and the U.S. negotiate their ethnic identity by looking at how these newcomers find a sense of belonging in Southern California in racial, social, and legal terms. Through an ethnographic approach of in-depth interviews and participant observation with six individuals, this case-study expands the available literature on transnationalism by exploring how Shin-Issei negotiations of identities rely on a transnational understandings of national ideologies of belonging which is a less direct form of transnationalism and is a more psychological, symbolic, and emotional reconciliation of self, encompassed between two worlds. -

AACP BOARD of DIRECTORS Florence M. Hongo, President Kathy Reyes, Vice President Rosie Shimonishi, Secretary Don Sekimura, Treasurer Leonard D

AACP BOARD OF DIRECTORS Florence M. Hongo, President Kathy Reyes, Vice President Rosie Shimonishi, Secretary Don Sekimura, Treasurer Leonard D. Chan Sutapa Dah Joe Chung Fong, PhD. Michele M. Kageura Susan Tanioka Sylvia Yeh Shizue Yoshina HONORARY BOARD Jerry Hiura Miyo Kirita Sadao Kinoshita Astor Mizuhara, In Memoriam Shirley Shimada Stella Takahashi Edison Uno, In Memoriam Hisako Yamauchi AACP OFFICE STAFF Florence M. Hongo, General Manager Mas Hongo, Business Manager Leonard D. Chan, Internet Consultant AACP VOLUNTEERS Beverly A. Ang, San Jose Philip Chin, Daly City Kiyo Kaneko, Sunnyvale Michael W. Kawamoto, San Jose Peter Tanioka, Merced Paul Yoshiwara, San Mateo Jaime Young AACP WELCOMES YOUR VOLUNTEER EFFORTS AACP has been in non-profit service for over 32 years. If you are interested in becoming an AACP volunteer, call us at (650) 357-1008 or (800) 874-2242. OUR MISSION To educate the public about the Asian American experience, fostering cultural awareness and to educate Asian Americans about their own heritage, instilling a sense of pride. CREDITS Typesetting and Layout – Sue Yoshiwara Editor– Florence M. Hongo/ Sylvia Yeh Cover – F.M. Hongo/L. D. Chan TABLE OF CONTENTS GREETINGS TO OUR SUPPORTERS i ELEMENTARY (Preschool through Grade 4) Literature 1-6 Folktales 7-11 Bilingual 12-14 ACTIVITIES (All ages) 15-19 Custom T-shirts 19 INTERMEDIATE (Grades 5 through 8) Educational Materials 20-21 Literature 22-26 Anti-Nuclear 25-26 LITERATURE (High School and Adult) Anthologies 27-28 Cambodian American 28 Chinese American 28-32 Filipino -

The Politics of Transnational History Making: Japanese Immigrants on T

Eiichiro Azuma | The Politics of Transnational History Making: Japanese Immigrants on t... Page 1 of 28 http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/jah/89.4/azuma.html From The Journal of American History Vol. 89, Issue 4. Viewed December 3, 2003 15:52 EST Presented online in association with the History Cooperative. http://www.historycooperative.org The Politics of Transnational History Making: Japanese Immigrants on the Western 'Frontier,' 1927-1941 Eiichiro Azuma In 1927 Toga Yoichi, a Japanese immigrant in Oakland, California, published a chronological 1 history of what he characterized as 'Japanese development in America.' He explicated the meaning of that history thus: A great nation/race [minzoku] has a [proper] historical background; a nation/race disrespectful of history is doomed to self-destruction. It has been already 70 years since we, the Japanese, marked the first step on American soil. Now Issei [Japanese immigrants] are advancing in years, and the Nisei [the American- born Japanese] era is coming. I believe that it is worthy of having [the second generation] inherit the record of our [immigrant] struggle against oppression and hardships, despite which we have raised our children well and reached the point at which we are now. But, alas, we have very few treatises of our history [to leave behind]. Thirteen years later, a thirteen hundred-page masterpiece entitled Zaibei Nihonjinshi--Toga himself spearheaded the editing--completed that project of history writing.1 Not the work of trained academicians, this synthesis represented the collaboration of many Japanese immigrants, including the self-proclaimed historians who authored it, community leaders who provided subventions, and ordinary Issei residents who offered necessary information or purchased the product. -

Before Pearl Harbor 29

Part I Niseiand lssei Before PearlHarbor On Decemb er'7, 194L, Japan attacked and crippled the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. Ten weeks later, on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 under which the War De- partment excluded from the West Coast everyone of Japanese ances- try-both American citizens and their alien parents who, despite long residence in the United States, were barred by federal law from be- coming American citizens. Driven from their homes and farms and "relocation businesses, very few had any choice but to go to centers"- Spartan, barrack-like camps in the inhospitable deserts and mountains of the interior. * *There is a continuing controversy over the contention that the camps "concentration were camps" and that any other term is a euphemism. The "concentration government documents of the time frequently use the term camps," but after World War II, with full realization of the atrocities committed by the Nazis in the death camps of Europe, that phrase came to have a very different meaning. The American relocation centers were bleak and bare, and life in them had many hardships, but they were not extermination camps, nor did the American government embrace a policy of torture or liquidation of the "concentration To use the phrase camps summons up images ethnic Japanese. "relo- ,and ideas which are inaccurate and unfair. The Commission has used "relocation cation centers" and camps," the usual term used during the war, not to gloss over the hardships of the camps, but in an effort to {ind an historically fair and accurate phrase. -

A Japanese View of “The Other World” Reflected in the Movie “Departures

13. A Japanese view of the Other World reflected in the movie “Okuribito (Departures)” Keiko Tanita Introduction Religion is the field of human activities most closely related to the issue of death. Japan is considered to be a Buddhist country where 96 million people support Buddhism with more than 75 thousands temples and 300 thousands Buddha images, according to the Cultural Affaires Agency in 2009. Even those who have no particular faith at home would say they are Buddhist when asked during their stay in other countries where religion is an important issue. Certainly, a great part of our cultural tradition is that of Buddhism, which was introduced into Japan in mid-6th century. Since then, Buddhism spread first among the aristocrats, then down to the common people in 13th century, and in the process it developed a synthesis of the traditions of the native Shintoism. Shintoism is a religion of the ancient nature and ancestor worship, not exactly the same as the present-day Shintoism which was institutionalized in the late 19th century in the course of modernization of Japan. Presently, we have many Buddhist rituals especially related to death and dying; funeral, death anniversaries, equinoctial services, the Bon Festival similar to Christian All Souls Day, etc. and most of them are originally of Japanese origin. Needless to say, Japanese Buddhism is not same as that first born in India, since it is natural for all religions to be influenced by the cultures specific to the countries/regions where they develop. Japanese Buddhism, which came from India through the Northern route of Tibet and China developed into what is called Mahayana Buddhism which is quite different from the conservative Theravada traditions found in Thai, Burmese, and Sri Lankan Buddhism, which spread through the Southern route. -

Folklife Bibliography by Joanne B

Folklife Bibliography By Joanne B. Mulcahy Aarne, Anti, and Stith Thompson. The Types of the Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communication No. 180. Helsinki, Finland: Academic Scientarum Fennica, 1960. Azuma, Eichiro. “A History of Oregon’s Issei, 1880–1952.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 94 (1993-94): 315–67. Barber, Katrine. “Stories Worth Recording: Martha McKeown and the Documentation of Pacific Northwest Life.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 110:4 (Winter 2009): 546-569. Beck, David R.M. “’Standing out Here in the Surf’: The Termination and Restoration of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians of Western Oregon in Historical Perspective.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 110:1 (Spring 2009): 6-37. Beckham, Steven Dow. Tall Tales from Rogue River: The Yarns of Hathaway Jones. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1974. Reprint, Oregon State University Press, 1991. _____. The Indians of Western Oregon: This Land Was Theirs. Coos Bay, OR: Arago Books, 1977. Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Translator.” In Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1969. Berg, Laura, ed. The First Oregonians. Portland: Oregon Council for the Humanities, 2007. Browner, Tara. Heartbeat of the People: Music and Dance of the Northern Pow-Wow. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002. Brunvand, Jan Harold. The Vanishing Hitchhiker: Urban Legends and Their Meanings. New York: W.W. Norton, 1981. Buan, Carolyn M., and Richard Lewis. The First Oregonians: An Illustrated Collection of Essays on Traditional Lifeways, Federal-Indian Relations, and the State’s Native People Today. Portland: Oregon Council for the Humanities, 1991. Cannon, Hal, ed. New Cowboy Poetry: A Contemporary Gathering. Layton, UT: Peregrine Smith Books, 1990. -

From Japonés to Nikkei: the Evolving Identities of Peruvians of Japanese

From japonés to Nikkei: The Evolving Identities of Peruvians of Japanese Descent by Eszter Rácz Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Professor Szabolcs Pogonyi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2019 Abstract This thesis investigates what defines the identity of third- and fourth-generation Japanese Peruvians and what is the current definition of Nikkei ethnic belonging on personal as well as institutional level. I look at the identity formation processes of Peruvians with ethnic Japanese background in light of the strong attachment to Japan as an imagined homeland, the troubled history of anti-Japanese discrimination in Peru and US internment of Japanese Peruvians during World War II, the consolidation of Japanese as a high-status minority, and ethnic return migration to Japan from 1990. Ethnicity has been assumed to be the cornerstone of identity in both Latin America where high sensitivity for racial differences results in intergenerational categorization and Japan where the essence of Japaneseness is assumed to run through one’s veins and passed on to further generations even if they were born and raised abroad. However when ethnic returnees arrived to Japan they had to realize that they were not Japanese by Japanese standards and chose to redefine themselves, in the case of Japanese Peruvians as Nikkei. I aim to explore the contents of the Japanese Peruvian definition of Nikkei by looking at existing literature and conducting video interviews through Skype and Messenger with third- and fourth-generation Japanese Peruvians. I look into what are their personal experiences as Nikkei, what changes do they recognize as the consequence of ethnic return migration, whether ethnicity has remained the most relevant in forming social relations, and what do they think about Japan now that return migration is virtually ended and the visa that allowed preferential access to Japanese descendants is not likely to be extended to further generations. -

Japanese Americans in the Pacific Before World War II

A Transnational Generation: Japanese Americans in the Pacific before World War II Michael JIN By the eve of the Second World War, thousands of second-generation Japanese Americans (Nisei) had lived and traveled outside the United States. Most of them had been sent to Japan at young ages by their first-generation (Issei) parents to be raised in the households of their relatives and receive proper Japanese education. Others were there on short-term tours sponsored by various Japanese organizations in the U.S. to experience the culture and society of their parents’ homeland. Many also sought opportunities for employment or higher education in a country that represented an expanding colonial power especially during the 1930s. Although no official data exists to help determine the exact number of Nisei in Japan before the Pacific War, various sources suggest that about 50,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry spent some of their formative years in Japan. Of these Nisei, 10,000-20,000 returned to the United States before the outbreak of Pearl Harbor and became known as Kibei (literally, “returned to America”). 1) The Nisei who migrated to Japan at young ages and those who embarked on subsequent journeys to Japan’s colonial world in the Pacific rarely appear in the popular narratives of Japanese American history. The U.S.-centered immigrant paradigm has confined the history of Nisei to the interior of U.S. political and cultural boundaries. Moreover, the Japanese American internment during World War II and the emphasis on Nisei loyalty and nationalism have been dominant themes in the postwar scholarship and public history of Japanese Americans. -

The Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture Edited by Yoshio Sugimoto Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88047-3 — The Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture Edited by Yoshio Sugimoto Index More Information Index 1955 system 116, 168 anti-Americanism 347 anti-authoritarianism 167 Abe, Kazushige 204–6 anti-globalisation protests 342–3 Abe, Shinzo¯ 59, 167, 172, 176, 347 anti-Japanese sentiment abortion 79–80, 87 in China 346–7 ‘Act for the Promotion of Ainu Culture & in South Korea 345, 347 Dissemination of Knowledge Regarding Aoyama, Nanae 203 Ainu Traditions’ 72 art-tested civility 170 aged care 77, 79, 89, 136–7, 228–9 Asada, Zennosuke 186 ageing population 123, 140 Asian identity 175–6, 214 participation in sporting activities 227–8 asobi (play) 218 aidagara (betweeness) 49 Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu) 243 Ainu language 71–2 audio-visual companies, export strategies Ainu people 362 banning of traditional practices 71 definition of 72 Balint, Michael 51 discrimination against 23 Benedict, Ruth 41 homeland 71 birthrate 81–5, 87, 140, 333–4 as hunters and meat eaters 304 Bon festival 221 overview 183 brain drain 144 Akitsuki, Risu 245 ‘bubble economy’ 118 All Romance Incident 189 Buddha (manga) 246 amae 41–2, 50–1 Buddhism 57, 59, 136 Amami dialects 63 background 149 Amami Islands 63 disassociation from Shinto under Meiji Amebic (novel) 209 152–6 The Anatomy of Dependence 40 effects of disassociation 153, 155–6 ancestor veneration 160–1 moral codes embodied in practice anime 15, 236 157 anime industry problems in the study of 151–2 criticisms of 237–8 as a rational philosophy 154 cultural erasure -

CONGRATULATIONS to the CLASS of 2020 Continue to Pursue Your Dreams from the Greater Seattle Awards Committee

VOLUME 28 FALL 2020 CONGRATULATIONS TO THE CLASS OF 2020 Continue to Pursue Your Dreams From the Greater Seattle Awards Committee We were so excited NSRCF decided that we personally to return to the Greater Seattle area contributed for its 40th anniversary. The local and raised awards committee is a passionate approximately and thoughtful group, comprised of $15,000 from the community and education leaders local community. who genuinely care about helping We also students gain access to higher dedicated education. Many of us were also $5,000 of the first-generation college students and locally raised we chose to serve on this committee funds to provide because of the huge opportunity for scholarships to Black Lives Matter us to give back and pay it forward. four Pacific Islander students. The Seattle Awards Committee would like to take a moment to Southeast Asian students are faced Thank you to the families, teachers, reflect on the racial injustices that are with barriers and challenges around and advisors who worked tirelessly happening in our nation amidst this language, gaps in mental health to support them. Thank you, pandemic. We as Asian Americans treatment, race-based bullying, students, for sharing your stories, and Pacific Islanders stand in and harassment that prevent hardships, and goals with us. It was solidarity with the Black Community many of them from obtaining inspiring tolearn how much you have and condemn the violence they face. higher education. To that end, we overcome, how you rise above the While the struggle for racial equality worked hard to ensure an inclusive, noise to reach your goals, and the and justice is ongoing, the turbulence accessible process, including ways you give back to your families of the past months must not providing workshops and tools to and communities. -

Traditional and Western Japanese American Musical Practices Before and During 1 Internment

Traditional and Western Japanese American Musical Practices Before and During 1 Internment Traditional and Western Japanese American Musical Practices Before and During Internment Joy Yamaguchi University of Minnesota Twin Cities Advisor: Erika Lee Traditional and Western Japanese American Musical Practices Before and During 2 Internment Introduction This paper will focus on two main genres of Japanese American music making - traditional Japanese music and western music – between two time periods – before and during internment. Prior to the internment, the demographic will highlight the lifestyle of Japanese Americans residing on the west coast, particularly those living within the four major Japanese American hubs: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Sacramento and Seattle. Within these cities, three major functions of musical activity will be highlighted prior to internment: Recreation, unification, and education. During Internment, this paper will utilize personal narratives of Nisei internees from four internment camps - Minidoka, Poston, Manzanar, Tule Lake – in order to depict changes in musical function and meaning. Within these camps, four major functions of musical activity will be highlighted: Recreation, Function, Control, and Resistance. In addition to the exploration of the evolution of musical function, this paper will also exhibit how changes in intergenerational relationships (Issei, first generation Japanese Americans, and Nisei, second generation Japanese Americans) are reflected in the changing function of musical practices,