A Japanese View of “The Other World” Reflected in the Movie “Departures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mariko Mori and the Globalization of Japanese “Cute”Culture

《藝術學研究》 2015 年 6 月,第十六期,頁 131-168 Mariko Mori and the Globalization of Japanese “Cute” Culture: Art and Pop Culture in the 1990s SooJin Lee Abstract This essay offers a cultural-historical exploration of the significance of the Japanese artist Mariko Mori (b. 1967) and her emergence as an international art star in the 1990s. After her New York gallery debut show in 1995, in which she exhibited what would later become known as her Made in Japan series— billboard-sized color photographs of herself striking poses in various “cute,” video-game avatar-like futuristic costumes—Mori quickly rose to stardom and became the poster child for a globalizing Japan at the end of the twentieth century. I argue that her Made in Japan series was created (in Japan) and received (in the Western-dominated art world) at a very specific moment in history, when contemporary Japanese art and popular culture had just begun to rise to international attention as emblematic and constitutive of Japan’s soft power. While most of the major writings on the series were published in the late 1990s, problematically the Western part of this criticism reveals a nascent and quite uneven understanding of the contemporary Japanese cultural references that Mori was making and using. I will examine this reception, and offer a counter-interpretation, analyzing the relationship between Mori’s Made in Japan photographs and Japanese pop culture, particularly by discussing the Japanese mass cultural aesthetic of kawaii (“cute”) in Mori’s art and persona. In so doing, I proffer an analogy between Mori and popular Japanimation characters, SooJin Lee received her PhD in Art History from the University of Illinois-Chicago and was a lecturer at the School of Art Institute of Chicago. -

Washoku Guidebook(PDF : 3629KB)

和 食 Traditional Dietary Cultures of the Japanese Itadaki-masu WASHOKU - cultures that should be preserved What exactly is WASHOKU? Maybe even Japanese people haven’t thought seriously about it very much. Typical washoku at home is usually comprised of cooked rice, miso soup, some main and side dishes and pickles. A set menu of grilled fish at a downtown diner is also a type of washoku. Recipes using cooked rice as the main ingredient such as curry and rice or sushi should also be considered as a type of washoku. Of course, washoku includes some noodle and mochi dishes. The world of traditional washoku is extensive. In the first place, the term WASHOKU does not refer solely to a dish or a cuisine. For instance, let’s take a look at osechi- ryori, a set of traditional dishes for New Year. The dishes are prepared to celebrate the coming of the new year, and with a wish to be able to spend the coming year soundly and happily. In other words, the religion and the mindset of Japanese people are expressed in osechi-ryori, otoso (rice wine for New Year) and ozohni (soup with mochi), as well as the ambience of the people sitting around the table with these dishes. Food culture has been developed with the background of the natural environment surrounding people and culture that is unique to the country or the region. The Japanese archipelago runs widely north and south, surrounded by sea. 75% of the national land is mountainous areas. Under the monsoonal climate, the four seasons show distinct differences. -

Taking Care of the Dead in Japan, a Personal View from an European Perspective Natacha Aveline

Taking care of the dead in Japan, a personal view from an European perspective Natacha Aveline To cite this version: Natacha Aveline. Taking care of the dead in Japan, a personal view from an European perspective. Chiiki kaihatsu, 2013, pp.1-5. halshs-00939869 HAL Id: halshs-00939869 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00939869 Submitted on 31 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Taking care of the dead in Japan, a personal view from an European perspective Natacha Aveline-Dubach Translation of the paper : N. Aveline-Dubach (2013) « Nihon no sôsôbijinesu to shisha no kûkan, Yoroppajin no me kara mite », Chiiki Kaihatsu (Regional Development) Chiba University Press, 8, pp 1-5. I came across the funeral issue in Japan in early 1990s. I was doing my PhD on the ‘land bubble’ in Tokyo, and I had the opportunity to visit one of the first —if not the first – large- scale urban renewal project involving the reconstruction of a Buddhist temple and its adjacent cemetery, the Jofuji temple 浄風寺 nearby the high-rise building district of West Shinjuku. The old outdoor cemetery of the Buddhist community had just been moved into the upper floors of the new multistory temple. -

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

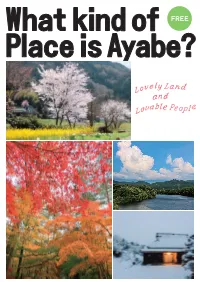

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

A Thesis Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki, Communal Illusion, and The

A Thesis entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki, Communal Illusion, and the Japanese New Left by Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for requirements for The Master of Arts Degree in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. William D. Hoover ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo (July 2005) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is customary in a note of acknowledgments to make the usual mea culpa concerning the impossibility of enumerating all the people to whom the author has incurred a debt in writing his or her work, but, in my case, this is far truer than I can ever say. This note is, therefore, a necessarily abbreviated one and I ask for a small jubilee, cancellation of all debts, from those that I fail to mention here due to lack of space and invidiously ungrateful forgetfulness. Prof. Peter Linebaugh, sage of the trans-Atlantic commons, who, as peerless mentor and comrade, kept me on the straight and narrow with infinite "grandmotherly kindness" when my temptation was always to break the keisaku and wander off into apostate digressions; conversations with him never failed to recharge the fiery voltage of necessity and desire of historical imagination in my thinking. The generously patient and supportive free rein that Prof. William D. Hoover, the co-chair of my thesis committee, gave me in exploring subjects and interests of my liking at my own preferred pace were nothing short of an ideal that all academic apprentices would find exceedingly enviable; his meticulous comments have time and again mercifully saved me from committing a number of elementary factual and stylistic errors. -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W Inte R 2 0 18 – 19

WINTER 2018–19 BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE 100 YEARS OF COLLECTING JAPANESE ART ARTHUR JAFA MASAKO MIKI HANS HOFMANN FRITZ LANG & GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM INGMAR BERGMAN JIŘÍ TRNKA MIA HANSEN-LØVE JIA ZHANGKE JAMES IVORY JAPANESE FILM CLASSICS DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT IN FOCUS: WRITING FOR CINEMA 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 CALENDAR DEC 9/SUN 21/FRI JAN 2:00 A Midsummer Night’s Dream 4:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 Introduction by Jan Pinkava 7:00 Fanny and Alexander BERGMAN P. 15 1/SAT TRNKA P. 12 3/THU 7:00 Full: Home Again—Tapestry 1:00 Making a Performance 1:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. 6 4:30 The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari P. 5 WORKSHOP P. 6 Reimagined Judith Rosenberg on piano 4–7 Five Tables of the Sea P. 4 5:30 The Good Soldier Švejk TRNKA P. 12 LANG & EXPRESSIONISM P. 16 22/SAT Free First Thursday: Galleries Free All Day 7:30 Persona BERGMAN P. 14 7:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 6:00 The Firemen’s Ball P. 29 5/SAT 2/SUN 12/WED 8:00 The Apartment P. 19 6:00 Future Landscapes WORKSHOP P. 6 12:30 Scenes from a 6:00 Arthur Jafa & Stephen Best 23/SUN Marriage BERGMAN P. 14 CONVERSATION P. 6 9/WED 2:00 Boom for Real: The Late Teenage 2:00 Guided Tour: Old Masters P. 6 7:00 Ugetsu JAPANESE CLASSICS P. 20 Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat P. 15 12:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. -

Japan: an Attempt at Interpretation

Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation Lafcadio Hearn Project Gutenberg's Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation, by Lafcadio Hearn #3 in our series by Lafcadio Hearn Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation Author: Lafcadio Hearn Release Date: June, 2004 [EBook #5979] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on October 5, 2002] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JAPAN *** [Transcriber's Note: Page numbers are retained in square brackets.] JAPAN AN ATTEMPT AT INTERPRETATION BY LAFCADIO HEARN 1904 Contents CHAPTER PAGE I. DIFFICULTIES.........................1 II. STRANGENESS AND CHARM................5 III. THE ANCIENT CULT....................21 IV. THE RELIGION OF THE HOME............33 V. -

Masaki Kobayashi: HARAKIRI (1962, 133M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

October 8, 2019 (XXXIX: 7) Masaki Kobayashi: HARAKIRI (1962, 133m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Masaki Kobayashi WRITING Shinobu Hashimoto wrote the screenplay from a novel by Yasuhiko Takiguchi. PRODUCER Tatsuo Hosoya MUSIC Tôru Takemitsu CINEMATOGRAPHY Yoshio Miyajima EDITING Hisashi Sagara The film was the winter of the Jury Special Prize and nominated for the Palm d’Or at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival. CAST Tatsuya Nakadai...Tsugumo Hanshirō (1979), Tokyo Trial* (Documentary) (1983), and Rentarō Mikuni...Saitō Kageyu Shokutaku no nai ie* (1985). He also wrote the screenplays Akira Ishihama...Chijiiwa Motome for A Broken Drum (1949) and The Yotsuda Phantom Shima Iwashita...Tsugumo Miho (1949). Tetsurō Tamba...Omodaka Hikokuro *Also wrote Ichiro Nakatani...Yazaki Hayato Masao Mishima...Inaba Tango SHINOBU HASHIMOTO (b. April 18, 1918 in Hyogo Kei Satō...Fukushima Masakatsu Prefecture, Japan—d. July 19, 2018 (age 100) in Tokyo, Yoshio Inaba...Chijiiwa Jinai Japan) was a Japanese screenwriter (71 credits). A frequent Yoshiro Aoki...Kawabe Umenosuke collaborator of Akira Kurosawa, he wrote the scripts for such internationally acclaimed films as Rashomon (1950) MASAKI KOBAYASHI (b. February 14, 1916 in and Seven Samurai (1954). These are some of the other Hokkaido, Japan—d. October 4, 1996 (age 80) in Tokyo, films he wrote for: Ikiru (1952), -

This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale CEAS Occasional Publication Series Council on East Asian Studies 2007 This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W. Kelly Yale University Atsuo Sugimoto Kyoto University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, William W. and Sugimoto, Atsuo, "This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan" (2007). CEAS Occasional Publication Series. Book 1. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Council on East Asian Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEAS Occasional Publication Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan j u % g b Edited by William W. KELLY With SUGIMOTO Atsuo YALE CEAS OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS VOLUME 1 This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan yale ceas occasional publications volume 1 © 2007 Council on East Asian Studies, Yale University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permis- sion. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. -

Trust in Japanese Management and Culture

DOCTORAT EN CO-ASSOCIATION ENTRE TELECOM ECOLE DE MANAGEMENT ET L ’UNIVERSITE D ’EVRY VAL D ’ESSONNES Spécialité: Sciences de Gestion Ecole doctorale: Sciences de la Société Présentée par William Evans Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE TELECOM ECOLE DE MANAGEMENT Trust in Japanese Management and Culture Soutenue le 19 / 12 / 2012 Devant le jury composé de : Directeur de thèse : Jean-Luc Moriceau, Professeur HDR à Télécom Ecole de Management Encadrant : Nabyla Daidj, Maître de conférences à Télécom Ecole de Management Rapporteurs : Rémi Jardat, Professeur HDR à l’ISTEC Maasaki Takemura, Associate Professor à Meiji University, Tokyo Examinateurs : Annick Ancelin-Bourguignon, Professeur HDR à Essec Business School Yvon Pesqueux, Professeur HDR au CNAM Richard Soparnot, Professeur HDR à l’ESCEM Thèse n° 2012 TELE 0048 Télécom Ecole de Management n’entend donner aucune approbation ni improbation aux opinions émises dans les thèses : ces opinions doivent être considérées comme propres à leurs auteurs. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my thesis supervisor and assistant supervisor, Jean-Luc Moriceau, PhD and Nabyla Daidj, PhD respectively. Mr. Moriceau’s pedagogic manner was extraordinary; calm and level-headed in advice and counsel, consistent in attention to the small and big issues, and deft in placing matters in context. Nabyla Daidj cast anchor, right at the start, to help me get focused and asked me the tough first questions and shared with me the right reading material. She meticulously guided me and helped dot the i’s and cross the t’s, consistently throughout the long process. They were a team and made me feel that they were there for me.