Trust in Japanese Management and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mariko Mori and the Globalization of Japanese “Cute”Culture

《藝術學研究》 2015 年 6 月,第十六期,頁 131-168 Mariko Mori and the Globalization of Japanese “Cute” Culture: Art and Pop Culture in the 1990s SooJin Lee Abstract This essay offers a cultural-historical exploration of the significance of the Japanese artist Mariko Mori (b. 1967) and her emergence as an international art star in the 1990s. After her New York gallery debut show in 1995, in which she exhibited what would later become known as her Made in Japan series— billboard-sized color photographs of herself striking poses in various “cute,” video-game avatar-like futuristic costumes—Mori quickly rose to stardom and became the poster child for a globalizing Japan at the end of the twentieth century. I argue that her Made in Japan series was created (in Japan) and received (in the Western-dominated art world) at a very specific moment in history, when contemporary Japanese art and popular culture had just begun to rise to international attention as emblematic and constitutive of Japan’s soft power. While most of the major writings on the series were published in the late 1990s, problematically the Western part of this criticism reveals a nascent and quite uneven understanding of the contemporary Japanese cultural references that Mori was making and using. I will examine this reception, and offer a counter-interpretation, analyzing the relationship between Mori’s Made in Japan photographs and Japanese pop culture, particularly by discussing the Japanese mass cultural aesthetic of kawaii (“cute”) in Mori’s art and persona. In so doing, I proffer an analogy between Mori and popular Japanimation characters, SooJin Lee received her PhD in Art History from the University of Illinois-Chicago and was a lecturer at the School of Art Institute of Chicago. -

Washoku Guidebook(PDF : 3629KB)

和 食 Traditional Dietary Cultures of the Japanese Itadaki-masu WASHOKU - cultures that should be preserved What exactly is WASHOKU? Maybe even Japanese people haven’t thought seriously about it very much. Typical washoku at home is usually comprised of cooked rice, miso soup, some main and side dishes and pickles. A set menu of grilled fish at a downtown diner is also a type of washoku. Recipes using cooked rice as the main ingredient such as curry and rice or sushi should also be considered as a type of washoku. Of course, washoku includes some noodle and mochi dishes. The world of traditional washoku is extensive. In the first place, the term WASHOKU does not refer solely to a dish or a cuisine. For instance, let’s take a look at osechi- ryori, a set of traditional dishes for New Year. The dishes are prepared to celebrate the coming of the new year, and with a wish to be able to spend the coming year soundly and happily. In other words, the religion and the mindset of Japanese people are expressed in osechi-ryori, otoso (rice wine for New Year) and ozohni (soup with mochi), as well as the ambience of the people sitting around the table with these dishes. Food culture has been developed with the background of the natural environment surrounding people and culture that is unique to the country or the region. The Japanese archipelago runs widely north and south, surrounded by sea. 75% of the national land is mountainous areas. Under the monsoonal climate, the four seasons show distinct differences. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

A Japanese View of “The Other World” Reflected in the Movie “Departures

13. A Japanese view of the Other World reflected in the movie “Okuribito (Departures)” Keiko Tanita Introduction Religion is the field of human activities most closely related to the issue of death. Japan is considered to be a Buddhist country where 96 million people support Buddhism with more than 75 thousands temples and 300 thousands Buddha images, according to the Cultural Affaires Agency in 2009. Even those who have no particular faith at home would say they are Buddhist when asked during their stay in other countries where religion is an important issue. Certainly, a great part of our cultural tradition is that of Buddhism, which was introduced into Japan in mid-6th century. Since then, Buddhism spread first among the aristocrats, then down to the common people in 13th century, and in the process it developed a synthesis of the traditions of the native Shintoism. Shintoism is a religion of the ancient nature and ancestor worship, not exactly the same as the present-day Shintoism which was institutionalized in the late 19th century in the course of modernization of Japan. Presently, we have many Buddhist rituals especially related to death and dying; funeral, death anniversaries, equinoctial services, the Bon Festival similar to Christian All Souls Day, etc. and most of them are originally of Japanese origin. Needless to say, Japanese Buddhism is not same as that first born in India, since it is natural for all religions to be influenced by the cultures specific to the countries/regions where they develop. Japanese Buddhism, which came from India through the Northern route of Tibet and China developed into what is called Mahayana Buddhism which is quite different from the conservative Theravada traditions found in Thai, Burmese, and Sri Lankan Buddhism, which spread through the Southern route. -

This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale CEAS Occasional Publication Series Council on East Asian Studies 2007 This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W. Kelly Yale University Atsuo Sugimoto Kyoto University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, William W. and Sugimoto, Atsuo, "This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan" (2007). CEAS Occasional Publication Series. Book 1. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Council on East Asian Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEAS Occasional Publication Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan j u % g b Edited by William W. KELLY With SUGIMOTO Atsuo YALE CEAS OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS VOLUME 1 This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan yale ceas occasional publications volume 1 © 2007 Council on East Asian Studies, Yale University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permis- sion. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. -

Policy of Cultural Affairs in Japan

Policy of Cultural Affairs in Japan Fiscal 2016 Contents I Foundations for Cultural Administration 1 The Organization of the Agency for Cultural Affairs .......................................................................................... 1 2 Fundamental Law for the Promotion of Culture and the Arts and Basic Policy on the Promotion of Culture and the Art ...... 2 3 Council for Cultural Affairs ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 4 Brief Overview of the Budget for the Agency for Cultural Affairs for FY 2016 .......................... 6 5 Commending Artistic and Related Personnel Achievement ...................................................................... 11 6 Cultural Publicity ............................................................................................................................................................................... 12 7 Private-Sector Support for the Arts and Culture .................................................................................................. 13 Policy of Cultural Affairs 8 Cultural Programs for Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games .................................................. 15 9 Efforts for Cultural Programs Taking into Account Changes Surrounding Culture and Arts ... 16 in Japan II Nurturing the Dramatic Arts 1 Effective Support for the Creative Activities of Performing Arts .......................................................... 17 2 -

Life and Culture of Japan- by Ms. Bina Pillai

JOURNAL OF ASIAN ARTS, CULTURE AND LITERATURE (JAACL) VOL 1, NO 1: MARCH 2020 Life and Culture of Japan By Ms. Bina Pillai [email protected] Abstract Japan is famous worldwide for its traditional arts, and people talk about their tea ceremonies, calligraphy and flower arrangement. The country is also known for its distinctive gardens, sculpture and poetry. Japan is home to more than a dozen UNESCO World Heritage sites and is the birthplace of sushi. Keywords Japan, cherry-blossom, Shinto, Buddhism, Okinawa, Sushi, Ikigai, Kyoto Introduction The culture and art of Japan is fascinating to me. Japanese art covers a wide range of art styles and media, which includes ancient pottery, sculpture, ukiyo-e paintings, woodblock prints, ink painting and calligraphy on silk and paper, ceramics, origami. Recently manga which is modern Japanese cartoons and comics along with a myriad of other types has also become popular. My nephew, who is the captain of a ship narrated this interesting anecdote about Japanese culture. His ship belongs to a Japanese company. Since the year 2000, he has been travelling to Japan every six months, and loves the place and the people out there, just the way he loves India. The owner of this shipping company is a tycoon. He owns hotels, clubs and spas but his only son works in the ship at grass roots level. The son does not get to enjoy any luxuries. He works along with the other staff roughing it out. However this helps in the child being humble in spite of his parents being wealthy. -

JAPANESE FOOD CULTURE Enjoying the Old and Welcoming the New

For more detailed information on Japanese government policy and other such matters, see the following home pages. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Website http://www.mofa.go.jp/ Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ JAPANESE FOOD CULTURE Enjoying the old and welcoming the new Rice The cultivation and consumption of rice has always played a central role in Japanese food culture. Almost ready for harvesting, this rice field is located near the base of the mountain Iwakisan in Aomori Prefecture. © Aomori prefecture The rice-centered food culture of Japan and imperial edicts gradually eliminated the evolved following the introduction of wet eating of almost all flesh of animals and fowl. rice cultivation from Asia more than 2,000 The vegetarian style of cooking known as years ago. The tradition of rice served with shojin ryori was later popularized by the Zen seasonal vegetables and fish and other marine sect, and by the 15th century many of the foods products reached a highly sophisticated form and food ingredients eaten by Japanese today Honzen ryori An example of this in the Edo period (1600-1868) and remains had already made their debut, for example, soy formalized cuisine, which is the vibrant core of native Japanese cuisine. In sauce (shoyu), miso, tofu, and other products served on legged trays called honzen. the century and a half since Japan reopened made from soybeans. Around the same time, © Kodansha to the West, however, Japan has developed an a formal and elaborate incredibly rich and varied food culture that style of banquet cooking includes not only native-Japanese cuisine but developed that was derived also many foreign dishes, some adapted to from the cuisine of the Japanese tastes and some imported more or court aristocracy. -

Japanese Approaches to the Meaning of Religion

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Faculty Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship Winter 1-1-2010 Beyond Belief: Japanese Approaches to the Meaning of Religion James Shields Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/fac_journ Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shields, James. "Beyond Belief: Japanese Approaches to the Meaning of Religion." Studies in Religion / Sciences religieuses (2010) : 133-149. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studies in Religion / Sciences Religieuses 000(00) 1–17 ª The Author(s) / Le(s) auteur(s), 2010 Beyond Belief: Japanese Reprints and permission/ Reproduction et permission: Approaches to the sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0008429810364118 Meaning of Religion sr.sagepub.com James Mark Shields Bucknell University, USA Abstract: For several centuries, Japanese scholars have argued that their nation’s culture—including its language, religion and ways of thinking—is somehow unique. The darker side of this rhetoric, sometimes known by the English term “Japanism” (nihon-jinron), played no small role in the nationalist fervor of the early late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. While much of the so-called “ideology of Japanese uniqueness” can be dismissed, in terms of the Japanese approach to “religion,” there may be something to it. -

Chapter 8- Shinto Teaching Tips

Sullivan, Religions of the World (Fortress Press, 2013) Chapter 8- Shinto Teaching Tips Approach to Teaching Shinto is often seen as a very optimistic religion. It has enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with Buddhism such that Buddhism will perform Shinto funerals and Shinto performs Buddhist weddings. This unity is also observed in their shrines and temples. For instance you could see a Buddhism temple with a Shinto shrine and via versa. One of the ways Buddhism has influenced Shinto is in regard to its ethical system. Shinto is often thought of as not having any sense of internal guilt, because they do believe in a moralistic God who gives a list of ethical guidelines. Discuss. Is it possible for human beings not to have a sense of internal guilt? Shinto is not a well known religion for many, consequently the video with Ben Kingsely might be a helpful introduction. The teacher might want to start here. Shinto has historically maintained its relevance to society by demonstrating four basic concerns An esteem for nature Benevolence silence on most moral and doctrinal issues Aesthetically pleasing rituals Emphasis on Eclecticism The teacher might spark a discussion on whether or not religions should be concern about the environment. For some people religion should be concerned with only that which is spiritual. Hence environmental concerns might not fit. This discussion can play into the age old conflict between religion and science. Shinto is very concerned about the environment. Human beings are seen as an extension of their environment. Consequently, the environment must be preserved. A similar discussion could evolve around the issue of passivism versus being a pacifist in religions. -

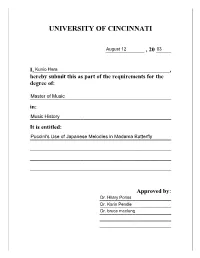

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere -

The Taste of Japan

Leiden University Date: 21-8-2014 MA Asian Studies: East Asian Studies Melvin de Kuyper (0985678) The Taste of Japan Connections between local dishes and travel in the contemporary food culture of Japan. Word Count: 14.984 Supervisor of Thesis: Prof. Dr. Smits Table of Contents: Introduction_________________________________________________ p. 3 Chapter 1: Modern Cuisine of Japan _____________________________ pp. 4 - 7 Chapter 2: Nostalgia and Travel in Japan _________________________ pp. 8 - 11 Chapter 3: Local Heritage Branding _____________________________ pp. 12 – 18 Final Remarks on Chapters 1 - 3 ________________________________ pp. 19 – 20 Case Study 1: Local Brand in Japanese gourmet television programs ____ pp. 21 – 30 Case Study 2: Local Food Advertisement in Travel Guides and Websites _ pp. 31 – 34 Conclusion __________________________________________________ pp. 35 – 36 Reference List _______________________________________________ pp. 38 - 42 2 Introduction Food is inextricably linked to culture. This is the case for everywhere in the world. As such, the food culture of Japan has also been a popular topic for numerous scholars to understand Japanese society. This thesis seeks to understand why local dishes and foodstuffs are popular in Japan, and why travel is closely connected to the food culture of Japan. To that aim, I will review the historical process and transformation of the food culture of Japan The first part of my thesis consist of building a historical and theoretical framework; the second part is devote to case studies. I will explain in the first chapter why the modern cuisine of Japan has been characterized as a “national cuisine”. I will show that contemporary studies have been focusing mainly on the creation of a single, more or less standardized Japanese cuisine, rather than on variations in local cuisine.