Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Other Top Reasons to Visit Hakone

MAY 2016 Japan’s number one English language magazine Other Top Reasons to Visit Hakone ALSO: M83 Interview, Sake Beauty Secrets, Faces of Tokyo’s LGBT Community, Hiromi Miyake Lifts for Gold, Best New Restaurants 2 | MAY 2016 | TOKYO WEEKENDER 7 17 29 32 MAY 2016 guide radar 26 THE FLOWER GUY CULTURE ROUNDUP THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS Nicolai Bergmann on his upcoming shows and the impact of his famed flower boxes 7 AREA GUIDE: EBISU 41 THE ART WORLD Must-see exhibitions including Ryan McGin- Already know the neighborhood? We’ve 28 JUNK ROCK ley’s nudes and Ville Andersson’s “silent” art thrown in a few new spots to explore We chat to M83 frontman Anthony Gon- zalez ahead of his Tokyo performance this 10 STYLE WISH LIST 43 MOVIES month Three films from Japanese distributor Gaga Spring fashion for in-between weather, star- that you don’t want to miss ring Miu Miu pumps and Gucci loafers 29 BEING LGBT IN JAPAN To celebrate Tokyo Rainbow Pride, we 12 TRENDS 44 AGENDA invited popular personalities to share their Escape with electro, join Tokyo’s wildest mat- Good news for global foodies: prepare to experiences suri, and be inspired at Design Festa Vol. 43 enjoy Greek, German, and British cuisine 32 BEAUTY 46 PEOPLE, PARTIES, PLACES The secrets of sake for beautiful skin, and Dewi and her dogs hit Yoyogi and Leo in-depth Andaz Tokyo’s brand-new spa menu COFFEE-BREAK READS DiCaprio comes to town 17 HAKONE TRAVEL SPECIAL 34 GIRL POWER 50 BACK IN THE DAY Our nine-page guide offers tips on what to Could Hiromi Miyake be Japan’s next This month in 1981: “Young Texan Becomes do, where to stay, and how to get around gold-winning weightlifter? Sumodom’s 1st Caucasian Tryout” TOKYO WEEKENDER | MAY 2016 | 3 THIS MONTH IN THE WEEKENDER Easier navigation Keep an eye out for MAY 2016 a new set of sections that let you, the MAY 2016 reader, have a clear set of what’s going where. -

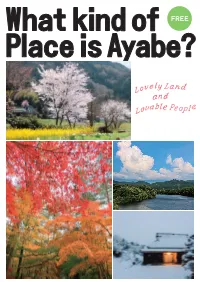

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2015 Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon Eric Teixeira Mendes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Asian History Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, and the History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons Recommended Citation Mendes, Eric Teixeira, "Ancient Magic and Modern Accessories: Developments in the Omamori Phenomenon" (2015). Master's Theses. 626. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/626 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON by Eric Teixeira Mendes A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Comparative Religion Western Michigan University August 2015 Thesis Committee: Stephen Covell, Ph.D., Chair LouAnn Wurst, Ph.D. Brian C. Wilson, Ph.D. ANCIENT MAGIC AND MODERN ACCESSORIES: DEVELOPMENTS IN THE OMAMORI PHENOMENON Eric Teixeira Mendes, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2015 This thesis offers an examination of modern Japanese amulets, called omamori, distributed by Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines throughout Japan. As amulets, these objects are meant to be carried by a person at all times in which they wish to receive the benefits that an omamori is said to offer. In modern times, in addition to being a religious object, these amulets have become accessories for cell-phones, bags, purses, and automobiles. -

Childbearing in Japanese Society: Traditional Beliefs and Contemporary Practices

Childbearing in Japanese Society: Traditional Beliefs and Contemporary Practices by Gunnella Thorgeirsdottir A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Social Sciences School of East Asian Studies August 2014 ii iii iv Abstract In recent years there has been an oft-held assumption as to the decline of traditions as well as folk belief amidst the technological modern age. The current thesis seeks to bring to light the various rituals, traditions and beliefs surrounding pregnancy in Japanese society, arguing that, although changed, they are still very much alive and a large part of the pregnancy experience. Current perception and ideas were gathered through a series of in depth interviews with 31 Japanese females of varying ages and socio-cultural backgrounds. These current perceptions were then compared to and contrasted with historical data of a folkloristic nature, seeking to highlight developments and seek out continuities. This was done within the theoretical framework of the liminal nature of that which is betwixt and between as set forth by Victor Turner, as well as theories set forth by Mary Douglas and her ideas of the polluting element of the liminal. It quickly became obvious that the beliefs were still strong having though developed from a person-to- person communication and into a set of knowledge aquired by the mother largely from books, magazines and or offline. v vi Acknowledgements This thesis would never have been written had it not been for the endless assistance, patience and good will of a good number of people. -

Festival/Tokyo Press Release

Festival Outline Name Festival/Tokyo 09 spring Time・Venues Feb 26 (Thu) – Mar 29 (Sun), 2009 Tokyo Metropolitan Art Space Medium Hall, Small Hall 1&2 Owlspot Theater (Toshima Performing Arts Center) Nishi-Sugamo Arts Factory, and others Program 14 performances presented by Festival/Tokyo 5 performances co-presented by Festival/Tokyo Festival/Tokyo Projects (Symposium/Station/Crew) Organized by Tokyo Metropolitan Government Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture Festival/Tokyo Executive Committee Toshima City, Toshima Future Culture Foundation, Arts Network Japan (NPO-ANJ) Co-organized by Japanese Centre of International Theatre Institute (ITI/UNESCO) Co-produced by The Japan Foundation Sponsored by Asahi Breweries, Ltd., Shiseido Co., Ltd. Supported by Asahi Beer Arts Foundation Endorsed by Ministry of Foreign Affairs, GEIDANKYO, Association of Japanese Theatre Companies Co-operated by The Tokyo Chamber of Commerce and Industry Toshima, Toshima City Shopping Street Federation, Toshima City Federation, Toshima City Tourism Association, Toshima Industry Association, Toshima Corporation Association Co-operated by Poster Hari’s Company Supported by the Agency for Cultural Affairs Government of Japan Related projects Tokyo Performing Arts Market 2009 2 Introduction Stimulated by the distinctive power of the performing arts and the abundant imagination of the artists, Tokyo Metropolitan Government and the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture launches a new performing arts festival, the Festival/Tokyo, together with the Festival/Tokyo Executive Committee (Toshima City, Toshima Future Cultural Foundation and NPO Arts Network Japan), as part of the Tokyo Culture Creation Project, a platform for strong communication and “real” experiences. The first Festival/Tokyo will be held from February 26 to March 29 in three main venues in the Ikebukuro and Toshima area, namely the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Space, Owlspot Theater and the Nishi-Sugamo Art Factory. -

A Japanese View of “The Other World” Reflected in the Movie “Departures

13. A Japanese view of the Other World reflected in the movie “Okuribito (Departures)” Keiko Tanita Introduction Religion is the field of human activities most closely related to the issue of death. Japan is considered to be a Buddhist country where 96 million people support Buddhism with more than 75 thousands temples and 300 thousands Buddha images, according to the Cultural Affaires Agency in 2009. Even those who have no particular faith at home would say they are Buddhist when asked during their stay in other countries where religion is an important issue. Certainly, a great part of our cultural tradition is that of Buddhism, which was introduced into Japan in mid-6th century. Since then, Buddhism spread first among the aristocrats, then down to the common people in 13th century, and in the process it developed a synthesis of the traditions of the native Shintoism. Shintoism is a religion of the ancient nature and ancestor worship, not exactly the same as the present-day Shintoism which was institutionalized in the late 19th century in the course of modernization of Japan. Presently, we have many Buddhist rituals especially related to death and dying; funeral, death anniversaries, equinoctial services, the Bon Festival similar to Christian All Souls Day, etc. and most of them are originally of Japanese origin. Needless to say, Japanese Buddhism is not same as that first born in India, since it is natural for all religions to be influenced by the cultures specific to the countries/regions where they develop. Japanese Buddhism, which came from India through the Northern route of Tibet and China developed into what is called Mahayana Buddhism which is quite different from the conservative Theravada traditions found in Thai, Burmese, and Sri Lankan Buddhism, which spread through the Southern route. -

This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale CEAS Occasional Publication Series Council on East Asian Studies 2007 This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W. Kelly Yale University Atsuo Sugimoto Kyoto University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, William W. and Sugimoto, Atsuo, "This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan" (2007). CEAS Occasional Publication Series. Book 1. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Council on East Asian Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEAS Occasional Publication Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan j u % g b Edited by William W. KELLY With SUGIMOTO Atsuo YALE CEAS OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS VOLUME 1 This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan yale ceas occasional publications volume 1 © 2007 Council on East Asian Studies, Yale University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permis- sion. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. -

1 4 Temesgen Assefa Case Study of Tokyo

City Tourism Performance Research Report for Case Study “Tokyo” By: Temesgen Assefa (Ph.D.) September 2nd , 2017 JTB Tourism Research & Consulting Co 1 Overview • Tokyo is the world’s largest city with more than 13 million inhabitants. Key Facts • Region & island: Located in Kanto region & Honshu island • Division: 23 special wards, 26 cities, and 4 sub-prefectures • Population - Metropolis: 13.5 million - 23 Wards: 8.9 million - Metropolitan: 37.8 million • Area: 2,190 sq.km • GDP: JPY 94.9 trillion (EUR 655 billion) (as of 2014) Source: Tokyo Metropolitan Government JTB Tourism Research & Consulting Co 2 Selected Flagship Attractions • Tokyo has mixes of modern and traditional attractions ranging from historic temples to skyscrapers. Figure 1.1 Tokyo Tower Figure 1.3 Shibuya Crossing Figure 1.5 Tokyo Marathon Figure 1.2 Asakusa Sensoji Kaminarimon Figure 1.4 Rikugien Garden Figure 1.6 Sumidagawa Fireworks Source: Tokyo Convention & Visitros Bureau JTB Tourism Research & Consulting Co 3 Introduction: Major Historical Timelines • The history of the city of Tokyo, originally named Edo, stretches back some 400 years. 1603-1867 1941 1964 2016 • In 1603, Tokugawa • Port of Tokyo opens • Olympic Games held in • The first women Ieyasu established 1947 Tokyo Shogunate Government Governor of Tokyo in Edo town 1912-1926 • New local self- • The shinkansen (Bullet 2010 was elected and a • In 1867, the Shogunate • In 1923 Tokyo was government system train) line began • Haneda Airport puts Government resigns and devastated by the Great new comprehensive established operations returns power to the Kanto Earthquake new runway and Emperor four-year plan was • In 1927, the first • Tokyo launches 23 • The Metropolitan international terminal formulated. -

Japanese Musical Performance and Diaspora

Japanese Musical Performance and Diaspora Andrew N. Weintraub Contract laborers from Japan were brought to Hawai'i in large numbers beginning in 1885. The first generation of Japanese immigrants, or issei, were primarily farmers, fishermen, and country folk. By 1920, forty percent of the population in Hawai'i was Japanese. Issei immigrants paved the way for their children (nisei, or second generation), grandchildren (sansei, or third generation), and great-grandchildren (yonsei, or fourth generation). The Japanese impact on local Hawaiian culture can be seen in many areas, including foods, customs, architecture, and public music and dance festivals. Bon odori (or bon dance) in Hawai'i has endured many changes since the first group of issei arrived on the islands. During the plantation period (1880s to 1910s), the immigrants steadfastly kept the tradition alive despite low working wages, difficult living conditions, and isolation from their homeland. In the 1930s, with the new homeland established, the tradition was strengthened by new choreographies, new music, contests, and scheduled dances. During this time the bon dance became a popular social event that appealed particularly to the younger generation. After the outbreak of World War II in December 1941, priests were detained, temples were closed, and Japanese were discouraged from gathering in large numbers. It became dangerous for Japanese to make any public expressions of national pride. Bon dance activities probably did not take place again until after the war ended in 1945. But during the 1950s and 1960s, a revival of bon odori took place. In addition to temple festivals, bon dances were sponsored by groups outside the temples for non-religious functions. -

Representations of the World Axis in the Japanese and the Romanian Culture

CONCORDIA DISCORS vs DISCORDIA CONCORS Representations of the World Axis in the Japanese and the Romanian Culture Renata Maria RUSU Japan Foundation Fellow 2009 – 2010 Handa City, Japan Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to briefly present some of the forms the world axis takes in Japanese and Romanian cultures through the ages, namely, to show how a mythological concept – the axis mundi – has outlived its mythological existence and has survived up to modern days. We do not intend to concentrate on similarities or differences, but simply present some of the many culture-specific representations of this universal mythological concept: world axis representations in modern Japanese festivals (of which we have chosen three, to represent “pillar torches”: “the Sakaki sacred tree”, “the sacred mountain”, and “the sacred pillar”) and some world axis representations in Romanian culture, such as the fir tree, symbols related to dendrolatry, wooden crosses placed at crossroads, the ritual of climbing mountains, etc. Keywords: axis mundi, myth, representation, culture 0. Introduction The concept of axis mundi is one of the mythological concepts that can be found in virtually all cultures in the world. It has many representations which depend on culture, such as the tree, the mountain, the pillar, the tower, the obelisk, the cross, the liana, the stars, the nail, the bridge, the stair, etc. What is also striking about this concept is that it managed to outlive its mythological representations and survive up to modern days – a very powerful metaphor that transcends time. In this paper, we shall take a brief look at some of the forms the world axis takes in Japanese and Romanian cultures through the ages. -

An Ethnographic Study of Tattooing in Downtown Tokyo

一橋大学審査学位論文 Doctoral Dissertation NEEDLING BETWEEN SOCIAL SKIN AND LIVED EXPERIENCE: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF TATTOOING IN DOWNTOWN TOKYO McLAREN, Hayley Graduate School of Social Sciences Hitotsubashi University SD091024 社会的皮膚と生きられた経験の間に針を刺す - 東京の下町における彫り物の民族誌的研究- ヘィリー・マクラーレン 一橋大学審査学位論文 博士論文 一橋大学大学院社会学研究科博士後期課程 i CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................... I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................ III NOTES ........................................................................................................................................ IV Notes on Language .......................................................................................................... iv Notes on Names .............................................................................................................. iv Notes on Textuality ......................................................................................................... iv Notes on Terminology ..................................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................... VI LIST OF WORDS .................................................................................................................... VIII INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ -

The Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture Edited by Yoshio Sugimoto Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88047-3 — The Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture Edited by Yoshio Sugimoto Index More Information Index 1955 system 116, 168 anti-Americanism 347 anti-authoritarianism 167 Abe, Kazushige 204–6 anti-globalisation protests 342–3 Abe, Shinzo¯ 59, 167, 172, 176, 347 anti-Japanese sentiment abortion 79–80, 87 in China 346–7 ‘Act for the Promotion of Ainu Culture & in South Korea 345, 347 Dissemination of Knowledge Regarding Aoyama, Nanae 203 Ainu Traditions’ 72 art-tested civility 170 aged care 77, 79, 89, 136–7, 228–9 Asada, Zennosuke 186 ageing population 123, 140 Asian identity 175–6, 214 participation in sporting activities 227–8 asobi (play) 218 aidagara (betweeness) 49 Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu) 243 Ainu language 71–2 audio-visual companies, export strategies Ainu people 362 banning of traditional practices 71 definition of 72 Balint, Michael 51 discrimination against 23 Benedict, Ruth 41 homeland 71 birthrate 81–5, 87, 140, 333–4 as hunters and meat eaters 304 Bon festival 221 overview 183 brain drain 144 Akitsuki, Risu 245 ‘bubble economy’ 118 All Romance Incident 189 Buddha (manga) 246 amae 41–2, 50–1 Buddhism 57, 59, 136 Amami dialects 63 background 149 Amami Islands 63 disassociation from Shinto under Meiji Amebic (novel) 209 152–6 The Anatomy of Dependence 40 effects of disassociation 153, 155–6 ancestor veneration 160–1 moral codes embodied in practice anime 15, 236 157 anime industry problems in the study of 151–2 criticisms of 237–8 as a rational philosophy 154 cultural erasure