Pdf (Last Accessed February 13, 2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American History Month Resources & Support Guide

African American History Month Resources & Support Guide A Selected List of Resources Library Hours Contact Us Monday—Friday 7:30 am-10:00pm Website http://www.ntc.edu/library Saturday—Sunday 9:00am-3:00pm Email [email protected] Phone 715.803.1115 SUGGESTED TERMS 14th Amendment Black Influence on Pop Culture Shirley Chisholm Abolition/Abolitionists Black Lives Matter Jazz Slavery and Europe Abraham Lincoln Black Panther Party Jim Crow Slavery and United States African American Brown v. Board of Education Loving v. Virginia, 1967 Slaves and War African American migration Civil Rights Movement Malcolm X Suffrage 1940 and 1960 Civil War National Association for the State of Florida v. George Zim- African Americans and sports Advancement of Colored Peo- merman Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. ple (NAACP) African Americans and war Underground Railroad Emancipation Proclamation Nelson Mandela Antebellum Urban housing Equal Protection Clause Poverty Apartheid Vel Phillips (Milwaukee) Frederick Douglass Sedition Barack and Michelle Obama Harlem CURRENT EVENTS As Barack Obama comes to Philadelphia, a look at his legacy Inside the Museum of African American History and Culture July 26, 2016 September 22, 2016 Source: Philadelphia Inquirer Source: Washington Informer Restoring Rights The new movie Loving chronicles the lengthy fight for interracial couples to get married in the U.S. Mildred and Richard Loving October 11, 2016 are the couple behind the landmark Supreme Court case Source: Wausau Daily Herald November 22, 2016 Source: CBS This Morning STREAMING -

Why Ghana Should Implement Certain International Legal Instruments Relating to International Sale of Goods Transactions

WHY GHANA SHOULD IMPLEMENT CERTAIN INTERNATIONAL LEGAL INSTRUMENTS RELATING TO INTERNATIONAL SALE OF GOODS TRANSACTIONS by Emmanuel Laryea* Abstract This article argues that Ghana should implement certain international legal instruments (ILIs) relating to international sale of goods transactions. It submits that the recommended instruments, if implemented, would harmonise Ghana’s laws with important aspects of laws that govern international sale of goods transactions; improve Ghana’s legal environment for such transactions; afford entities located in Ghana better facilitation and protection in their trade with foreign counterparts; and improve how Ghana is perceived by the international trading community. The ILIs recommended are the CISG, Rotterdam Rules, and amendments to the Ghanaian Electronic Transactions Act to align with the UNCITRAL Model on Electronic Commerce and Convention on the Use of Electronic Commerce in International Contracts. The recommended actions hold advantages for Ghana, have no material disadvantages, and are easy and inexpensive to implement. I. INTRODUCTION This article argues that Ghana should implement1 certain international legal instruments (ILIs) relating to international sale of goods transactions. The article submits that the recommended instruments, if adopted, would harmonise Ghana’s laws with aspects of laws that govern international sale of goods globally, and improve Ghana’s legal environment for international sale transactions. It would also afford entities located in Ghana better facilitation and protection in their trade with foreign counterparts, enhance their competitiveness in international sale transactions, and improve how Ghana is perceived by the international trading community.2 The recommended actions hold advantages, have no material disadvantages, and are easy and inexpensive to implement. -

Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-22-2019 Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality Emmanuella Amoh Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the African History Commons Recommended Citation Amoh, Emmanuella, "Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1067. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1067 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KWAME NKRUMAH, HIS AFRO-AMERICAN NETWORK AND THE PURSUIT OF AN AFRICAN PERSONALITY EMMANUELLA AMOH 105 Pages This thesis explores the pursuit of a new African personality in post-colonial Ghana by President Nkrumah and his African American network. I argue that Nkrumah’s engagement with African Americans in the pursuit of an African Personality transformed diaspora relations with Africa. It also seeks to explore Black women in this transnational history. Women are not perceived to be as mobile as men in transnationalism thereby underscoring their inputs in the construction of certain historical events. But through examining the lived experiences of Shirley Graham Du Bois and to an extent Maya Angelou and Pauli Murray in Ghana, the African American woman’s role in the building of Nkrumah’s Ghana will be explored in this thesis. -

The Beautiful Struggle of Black Feminism: Changes in Representations of Black Womanhood Examined Through the Artwork of Elizabet

Wayne State University Wayne State University Theses 1-1-2017 The Beautiful Struggle Of Black Feminism: Changes In Representations Of Black Womanhood Examined Through The Artwork Of Elizabeth Catlett And Mickalene Thomas Juana Williams Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_theses Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Juana, "The Beautiful Struggle Of Black Feminism: Changes In Representations Of Black Womanhood Examined Through The Artwork Of Elizabeth Catlett And Mickalene Thomas" (2017). Wayne State University Theses. 594. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_theses/594 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE BEAUTIFUL STRUGGLE OF BLACK FEMINISM: CHANGES IN REPRESENTATIONS OF BLACK WOMANHOOD EXAMINED THROUGH THE ARTWORK OF ELIZABETH CATLETT AND MICKALENE THOMAS by JUANA WILLIAMS THESIS Submitted to the Graduate School Of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF ARTS 2017 MAJOR: ART HISTORY Approved By: __________________________________________ Advisor Date © COPYRIGHT BY JUANA WILLIAMS 2017 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To Antwuan, Joy, Emee, and Ari. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my advisor Dr. Dora Apel for her guidance, encouragement, and support throughout my graduate career, especially during the period of writing my thesis. Her support has been invaluable and I am eternally grateful. I also wish to thank my second reader Dr. Samantha Noel for always offering insightful commentary on my writings. -

The Ground of Empowerment

THE GROUND OF EMPOWERMENT W. E. B. Du Bois and the Vision of Africa’s Past by Tracey Lynn Thompson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Tracey Lynn Thompson 2011 The Ground of Empowerment W. E. B. Du Bois and the Vision of Africa’s Past Tracey Lynn Thompson Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2011 Abstract Scholars have examined many aspects of W. E. B. Du Bois’s project of empowering oppressed peoples in the United States and around the world. However they have treated in only a fragmentary way one of the principal strategies that he used to counter hegemonic ideologies of African and African American inferiority. That strategy was to turn to the evidence of history. Here I argue that Du Bois, alerted by Franz Boas to Africans’ historical attainments, confronted claims made by European Americans that Africans and a fortiori African Americans lacked any achievement independent of European or other foreign influence. Du Bois linked African Americans to Africa and laid out repeatedly and in detail a narrative of autonomous African historical accomplishment. I demonstrate that his approach to the history of Africa constituted a radical departure from the treatment of Africa presented by scholars located in the mainstream of contemporary anglophone academic thought. I argue that while his vision of Africa’s history did not effect any significant shift in scholarly orthodoxy, it played a crucial role, at a grave juncture in race relations in the United States, in helping to equip young African Americans with the psychological resources necessary to challenge white supremacist systems. -

Malcolm X Bibliography 1985-2011

Malcolm X Bibliography 1985-2011 Editor’s Note ................................................................................................................................... 1 Books .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Books in 17 other languages ......................................................................................................... 13 Theses (BA, Masters, PhD) .......................................................................................................... 18 Journal articles .............................................................................................................................. 24 Newspaper articles ........................................................................................................................ 32 Editor’s Note The progress of scholarship is based on the inter-textuality of the research literature. This is about how people connect their work with the work that precedes them. The value of a work is how it interacts with the existing scholarship, including the need to affirm and negate, as well as to fill in where the existing literature is silent. This is the importance of bibliography, a research guide to the existing literature. A scholar is known by their mastery of the bibliography of their field of study. This is why in every PhD dissertation there is always a chapter for the "review of the literature." One of the dangers in Black Studies is that -

General Robert E. Lee (1807-70) and Philanthropist George Peabody (1795-1869) at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, July 23-Aug

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 444 917 SO 031 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty J. TITLE General Robert E. Lee (1807-70) and Philanthropist George Peabody (1795-1869) at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, July 23-Aug. 30, 1869. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 33p. PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Civil War (United States); *Donors; *Meetings; *Private Financial Support; *Public History; Recognition (Achievement); *Reconstruction Era IDENTIFIERS Biodata; Lee (Robert E); *Peabody (George) ABSTRACT This paper discusses the chance meeting at White Sulphur Springs (West Virginia) of two important public figures, Robert E. Lee and George Peabody, whose rare encounter marked a symbolic turn from Civil War bitterness toward reconciliation and the lifting power of education. The paper presents an overview of Lee's life and professional and military career followed by an overview of Peabody's life and career as a banker, an educational philanthropist, and one who endowed seven Peabody Institute libraries. Both men were in ill health when they visited the Greenbrier Hotel in the summer of 1869, but Peabody had not long to live and spent his time confined to a cottage where he received many visitors. Peabody received a resolution of praise from southern dignitaries which read, in part: "On behalf of the southern people we tender thanks to Mr. Peabody for his aid to the cause of education...and hail him benefactor." A photograph survives that shows Lee, Peabody, and William Wilson Corcoran sitting together at the Greenbrier. Reporting that Lee's own illness kept him from attending Peabody's funeral, the paper describes the impressive and prolonged international services in 1870. -

Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22

T HE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A TLANTIC SLAVERY AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD I BRAHIMA THIAW AND DEBORAH L. MACK, GUEST EDITORS A tlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Experiences, Representations, and Legacies An Introduction to Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy V The Slavery Business and the Making of “Race” in Britain OLUME 61 and the Caribbean Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME SUPPLEMENT 61 22 From Country Marks to DNA Markers: The Genomic Turn S UPPLEMENT 22 in the Reconstruction of African Identities Diasporic Citizenship under Debate: Law, Body, and Soul Slavery, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Racialization of Africans Sovereignty after Slavery: Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti O CTOBER 2020 From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The “Changing Same” of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants Serving Status on the Gambia River Before and After Abolition The Problem: Religion within the World of Slaves The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons A “tone of voice peculiar to New-England”: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy Raising -

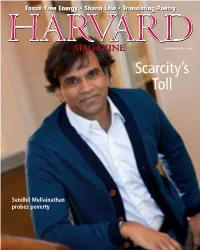

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

The Complex Relationship Between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement

The Gettysburg Historical Journal Volume 20 Article 8 May 2021 The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement Hannah Labovitz Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Labovitz, Hannah (2021) "The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 20 , Article 8. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol20/iss1/8 This open access article is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement Abstract The Civil Rights Movement occurred throughout a substantial portion of the twentieth century, dedicated to fighting for equal rights for African Americans through various forms of activism. The movement had a profound impact on a number of different communities in the United States and around the world as demonstrated by the continued international attention marked by recent iterations of the Black Lives Matter and ‘Never Again’ movements. One community that had a complex reaction to the movement, played a major role within it, and was impacted by it was the American Jewish community. The African American community and the Jewish community were bonded by a similar exclusion from mainstream American society and a historic empathetic connection that would carry on into the mid-20th century; however, beginning in the late 1960s, the partnership between the groups eventually faced challenges and began to dissolve, only to resurface again in the twenty-first century. -

Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin

Traut 1 Katerina Traut Lehigh University Giving ‘Substance to Freedom and Democracy’: Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin ABSTRACT: This paper explores labor organizer Vicki Garvin's life and ideas as an instantiation of Black feminism and as characterized by features central to contemporary Black feminist thought. Garvin's philosophy and practice of feminism come forth in her research and activism in worker’s rights, African American’s rights, and women’s rights. Garvin came of age in a post-WWII era of politics that was shaped by social movements toward liberation. As a demonstration of how to resist domination and oppression while remaining committed to the practice of democracy, Garvin's lifework deserves attention. INTRODUCTION According to Patricia Hill Collins, one distinguishing feature of Black feminist thought is that there is a dialectical relationship between oppression and activism, and there is a dialogical relationship between Black women's collective experiences of oppression and their group knowledge.1 Because of their unique position within the matrix of domination, defined as the social organization in which intersecting oppressions are developed, maintained, and maneuvered, African American women have a special knowledge about the interlocking nature of race, gender, and class oppression.2 Therefore, they must be a part of any effective effort to critique and overcome oppression. As Collins explains, this insight was known and practiced well before contemporary feminist thinkers such as herself conceptualized Black feminist thought as a particular field of scholarship. The research and activism of labor organizer Vicki Garvin demonstrates an understanding of the specific and important role that African American women (as one of many historically marginalized/oppressed groups) have to play within the Traut 2 institutional contexts that create and perpetuate their oppression. -

Joshua Myers

Joshua Myers Associate Professor, Howard University Department of Afro-American Studies Founders Library, Room 337 Washington, DC 20059 [email protected] Curriculum Vitae Education Ph.D. African American Studies, Temple University Thesis: “Reconceptualizing Intellectual Histories of Africana Studies: A Review of the Literature 2013 Committee: Nathaniel Norment, Jr., Ph.D., Greg Carr, Ph.D., Abu S. Abarry, Ph.D., E. L. Wonkeryor, Ph.D., Wilbert Jenkins, Ph.D. M.A. African American Studies, Temple University Thesis: “Reconceptualizing Intellectual Histories of Africana Studies: Preliminary Considerations 2011 Committee: Nathaniel Norment, Jr., Ph.D., Greg Carr, Ph.D. B.B.A. Finance, Howard University 2009 Research Interests Africana Studies, Disciplinarity, Intellectual History, Theories of Knowledge Academic Positions Associate Professor, Department of Afro- 2020-present American Studies, Howard University Assistant Professor, Department of Afro- 2014-2020 American Studies, Howard University Lecturer, Department of Afro-American Studies, Howard University 2013-2014 Graduate EXtern, Ronald McNair Ronald McNair Post-Baccalaureate Achievement Program, Summer Temple University 2011 Research Positions Research Assistantship, with Nathaniel Norment, 2010-2011 1 Jr., Ph.D. Research Assistant, Center for African American Research and Public Policy, Department of 2009- African American Studies, Temple University 2010 Publications Books Of Black Study (London: Pluto Press, under contract) Cedric Robinson: The Time of the Black Radical Tradition (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, in production) We are Worth Fighting For: A History of the Howard University Student Protest of 1989 (New York: New York University Press, 2019) Peer-Reviewed Articles “Organizing Howard.” Washington History (Fall 2020): 49-51. “The Order of Disciplinarity, The Terms of Silence.” Critical Ethnic Studies Journal 3 (Spring 2018): 107-29.