Black Identities in US-Caribbean Encounters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Meta-Regression Analysis on the Association Between Income Inequality and Intergenerational Transmission of Income

A meta-regression analysis on the association between income inequality and intergenerational transmission of income Ernesto F. L. Amaral Texas A&M University [email protected] Sharron X. Wang Texas A&M University [email protected] Shih-Keng Yen Texas A&M University [email protected] Francisco Perez-Arce University of Southern California [email protected] Abstract Our overall aim is to understand the association between income inequality and intergenerational transmission of income (degree to which conditions at birth and childhood determine socioeconomic situation later in life). Causality is hard to establish, because both income inequality and inequality in opportunity are results of complex social and economic outcomes. We analyze whether this correlation is observed across countries and time (as well as within countries), in a context of recent increases in income inequality. We investigate Great Gatsby curves and perform meta-regression analyses based on several papers on this topic. Results suggest that countries with high levels of income inequality tend to have higher levels of inequality of opportunity. Intergenerational income elasticity has stronger associations with Gini coefficient, compared to associations with top one percent income share. Once fixed effects are included for each country and study paper, these correlations lose significance. Increases in income inequality not necessarily bring decreases in intergenerational mobility maybe as a result of different drivers of inequality having diverse effects on mobility, as well as a consequence of public policies that might reduce associations between income inequality and inequality of opportunity. Keywords Income inequality. Intergenerational transmission of income. Intergenerational mobility. Inequality of opportunity. Great Gatsby Curve. -

Theminorityreport

theMINORITYREPORT The annual news of the AEA’s Committee on the Status of Minority Groups in the Economics Profession, the National Economic Association, and the American Society of Hispanic Economists Issue 11 | Winter 2019 Nearly a year after Hurricane Maria brought catastrophic PUERTO RICAN destruction across the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017, the governor of Puerto Rico MIGRATION AND raised the official death toll estimate from 64 to 2,975 fatalities based on the results of a commissioned MAINLAND report by George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health (2018). While other SETTLEMENT independent reports (e.g., Kishore et al. 2018) placed the death toll considerably higher, this revised estimate PATTERNS BEFORE represented nearly a tenth of a percentage point (0.09 percent) of Puerto Rico’s total population of 3.3 million AND AFTER Americans—over a thousand more deaths than the estimated 1,833 fatalities caused by Hurricane Katrina in HURRICANE MARIA 2005. Regardless of the precise number, these studies consistently point to many deaths resulting from a By Marie T. Mora, University of Texas Rio Grande lack of access to adequate health care exacerbated by the collapse of infrastructure (including transportation Valley; Alberto Dávila, Southeast Missouri State systems and the entire electrical grid) and the severe University; and Havidán Rodríguez, University at interruption and slow restoration of other essential Albany, State University of New York services, such as running water and telecommunications. -

Rhode Island College TESL 539: Language Acquisition and Learning Powerpoint Presentation: Ghana By: Gina Covino

Rhode Island College TESL 539: Language Acquisition and Learning PowerPoint Presentation: Ghana By: Gina Covino GHANA March 6, 1957 Table of Contents Part I. 1. Geography/Demographics 2. 10 Administrative Regions 3. Language Diversity 4. Politics Part II. 5. Education: Environment and Curriculum 6. Education: Factors 7. Education: Enrollment 8. Education: Literacy Rate Part III. 9. Culture, Values and Attitudes 10. Ghanaian Migrants Abroad 11. Ghanaian Americans Geography Demographics Population: 24,392,000 • Location: Ghana is in • Rural population: 49% Western Africa, bordering • Population below poverty level 28.5 % the Gulf of Guinea, • Ghana is a low income country with a between Cote d'Ivoire per capital GDP of only $402.7 (U.S.) per and Togo. year. • Capital: Accra Age structure: 0-14 years: 36.5% (male 4,568,273/female 4,468,939) 15-64 years: 60% (male 7,435,449/female 7,436,204) 65 years and over: 3.6% (male 399,737/female 482,471) Ethnic groups: Akan 47.5%, Mole-Dagbon 16.6%, Ewe 13.9% Ga-Dangme 7.4%, Gurma 5.7%, Guan 3.7%, Grusi 2.5%, Mande-Busanga 1.1%, 1 Reference: 15 Other 1.6% 10 Administrative Regions Region Regional Capital Northern Tamale Eastern Koforidua Western Takoradi Central Cape Coast Upper East Bolgatanga Upper West Wa Volta Ho Ashanti Kumasi Brong-Ahafo Sunyani Greater Accra Accra • About 70 percent of the total population lives in the southern half of the country. Accra and Kumasi are the largest settlement areas. Reference: 14 2 Language Diversity National Official Language: English • More than 60 languages and dialects are spoken in Ghana. -

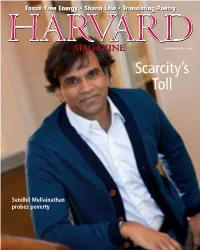

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

Literature, Peda

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts THE STUDENTS OF HUMAN RIGHTS: LITERATURE, PEDAGOGY, AND THE LONG SIXTIES IN THE AMERICAS A Dissertation in Comparative Literature by Molly Appel © 2018 Molly Appel Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 ii The dissertation of Molly Appel was reviewed and approved* by the following: Rosemary Jolly Weiss Chair of the Humanities in Literature and Human Rights Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Thomas O. Beebee Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Comparative Literature and German Charlotte Eubanks Associate Professor of Comparative Literature, Japanese, and Asian Studies Director of Graduate Studies John Ochoa Associate Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature Sarah J. Townsend Assistant Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Robert R. Edwards Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English and Comparative Literature Head of the Department of Comparative Literature *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT In The Students of Human Rights, I propose that the role of the cultural figure of the American student activist of the Long Sixties in human rights literature enables us to identify a pedagogy of deficit and indebtedness at work within human rights discourse. My central argument is that a close and comparative reading of the role of this cultural figure in the American context, anchored in three representative cases from Argentina—a dictatorship, Mexico—a nominal democracy, and Puerto Rico—a colonially-occupied and minoritized community within the United States, reveals that the liberal idealization of the subject of human rights relies upon the implicit pedagogical regulation of an educable subject of human rights. -

Transnational Identity and Second-Generation Black

THE DARKER THE FLESH, THE DEEPER THE ROOTS: TRANSNATIONAL IDENTITY AND SECOND-GENERATION BLACK IMMIGRANTS OF CONTINENTAL AFRICAN DESCENT A Dissertation by JEFFREY F. OPALEYE Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Joe R. Feagin Committee Members, Jane A. Sell Mary Campbell Srividya Ramasubramanian Head of Department, Jane A. Sell August 2020 Major Subject: Sociology Copyright 2020 Jeffrey F. Opaleye ABSTRACT Since the inception of the Immigration Act of 1965, Black immigrant groups have formed a historic, yet complex segment of the United States population. While previous research has primarily focused on the second generation of Black immigrants from the Caribbean, there is a lack of research that remains undiscovered on America’s fastest-growing Black immigrant group, African immigrants. This dissertation explores the transnational identity of second-generation Black immigrants of continental African descent in the United States. Using a transnational perspective, I argue that the lives of second-generation African immigrants are shaped by multi-layered relationships that seek to maintain multiple ties between their homeland and their parent’s homeland of Africa. This transnational perspective brings attention to the struggles of second-generation African immigrants. They are replicating their parents’ ethnic identities, maintaining transnational connections, and enduring regular interactions with other racial and ethnic groups while adapting to mainstream America. As a result, these experiences cannot be explained by traditional and contemporary assimilation frameworks because of their prescriptive, elite, white dominance framing and methods that were designed to explain the experiences of European immigrants. -

Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin

Traut 1 Katerina Traut Lehigh University Giving ‘Substance to Freedom and Democracy’: Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin ABSTRACT: This paper explores labor organizer Vicki Garvin's life and ideas as an instantiation of Black feminism and as characterized by features central to contemporary Black feminist thought. Garvin's philosophy and practice of feminism come forth in her research and activism in worker’s rights, African American’s rights, and women’s rights. Garvin came of age in a post-WWII era of politics that was shaped by social movements toward liberation. As a demonstration of how to resist domination and oppression while remaining committed to the practice of democracy, Garvin's lifework deserves attention. INTRODUCTION According to Patricia Hill Collins, one distinguishing feature of Black feminist thought is that there is a dialectical relationship between oppression and activism, and there is a dialogical relationship between Black women's collective experiences of oppression and their group knowledge.1 Because of their unique position within the matrix of domination, defined as the social organization in which intersecting oppressions are developed, maintained, and maneuvered, African American women have a special knowledge about the interlocking nature of race, gender, and class oppression.2 Therefore, they must be a part of any effective effort to critique and overcome oppression. As Collins explains, this insight was known and practiced well before contemporary feminist thinkers such as herself conceptualized Black feminist thought as a particular field of scholarship. The research and activism of labor organizer Vicki Garvin demonstrates an understanding of the specific and important role that African American women (as one of many historically marginalized/oppressed groups) have to play within the Traut 2 institutional contexts that create and perpetuate their oppression. -

Denkyem (Crocodile): Identity Developement and Negotiation Among Ghanain-American Millennials

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2019 Denkyem (Crocodile): identity developement and negotiation among Ghanain-American millennials. Jakia Marie University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African Studies Commons, Migration Studies Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Marie, Jakia, "Denkyem (Crocodile): identity developement and negotiation among Ghanain-American millennials." (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3315. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3315 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DENKYEM (CROCODILE): IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT AND NEGOTIATION AMONG GHANAIAN- AMERICAN MILLENNIALS By Jakia Marie B.A., Grand Valley State University, 2013 M.Ed., Grand Valley State University, 2016 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Pan-African Studies Department of Pan-African Studies University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2019 Copyright 2019 by Jakia Marie All rights reserved. DENKYEM: IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT AND NEGOTIATION AMONG GHANAIAN- AMERICAN MILLENNIALS By Jakia Marie B.A., Grand Valley State University, 2013 M.Ed., Grand Valley State University, 2016 A Dissertation Approved on November 1, 2019 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Pdf (Last Accessed February 13, 2015)

Notes Introduction 1. Perry A. Hall, In the Vineyard: Working in African American Studies (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1999), 17. 2. Naomi Schaefer Riley, “The Most Persuasive Case for Eliminating Black Studies? Just Read the Dissertations,” The Chronicle of Higher Education (April 30, 2012). http://chronicle.com/blogs/brainstorm/the-most-persuasive-case -for-eliminating-black-studies-just-read-the-dissertations/46346 (last accessed December 7, 2014). 3. William R. Jones, “The Legitimacy and Necessity of Black Philosophy: Some Preliminary Considerations,” The Philosophical Forum 9(2–3) (Winter–Spring 1977–1978), 149. 4. Ibid., 149. 5. Joseph Neff and Dan Kane, “UNC Scandal Ranks Among the Worst, Experts Say,” Raleigh News and Observer (Raleigh, NC) (October 25, 2014). http:// www.newsobserver.com/2014/10/25/4263755/unc-scandal-ranks-among -the-worst.html?sp=/99/102/110/112/973/. This is just one of many recent instances of “academic fraud” and sports that include Florida State University, University of Minnesota, University of Georgia and Purdue University. 6. Robert L. Allen, “Politics of the Attack on Black Studies,” in African American Studies Reader, ed. Nathaniel Norment (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2007), 594. 7. See Shawn Carrie, Isabelle Nastasia and StudentNation, “CUNY Dismantles Community Center, Students Fight Back,” The Nation (October 25, 2013). http://www.thenation.com/blog/176832/cuny-dismantles-community - center-students-fight-back# (last accessed February 17, 2014). Both Morales and Shakur were former CCNY students who became political exiles. Morales was involved with the Puerto Rican independence movement. He was one of the many students who organized the historic 1969 strike by 250 Black and Puerto Rican students at CCNY that forced CUNY to implement Open Admissions and establish Ethnic Studies departments and programs in all CUNY colleges. -

How Jamaican DACA Recipients Are Coping with the 2017 DACA Policy Change

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Education Doctoral Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. School of Education 12-2019 The Era of Trump: How Jamaican DACA Recipients are Coping with the 2017 DACA Policy Change Rachele M. Hall St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd Part of the Education Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Hall, Rachele M., "The Era of Trump: How Jamaican DACA Recipients are Coping with the 2017 DACA Policy Change" (2019). Education Doctoral. Paper 426. Please note that the Recommended Citation provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd/426 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Era of Trump: How Jamaican DACA Recipients are Coping with the 2017 DACA Policy Change Abstract The topic of undocumented immigrants living in the United States stimulates consistent national and local debate. In 2012 President Barack Obama signed an executive order creating the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy which provided undocumented immigrants work authorization and reprieve from deportation. In 2017, newly elected President Donald J. Trump announced the removal of the DACA policy. Researchers have focused on the impact of the removal of the DACA policy on undocumented Latino/a immigrants, but limited to no research has focused on the impact for Black immigrants, specifically those identifying as Jamaican. -

Multiculturalism, Afro-Descendant Activism, and Ethnoracial Law and Policy in Latin America

Rahier, Jean Muteba. 2020. Multiculturalism, Afro-Descendant Activism, and Ethnoracial Law and Policy in Latin America. Latin American Research Review 55(3), pp. 605–612. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.1094 BOOK REVIEW ESSAYS Multiculturalism, Afro-Descendant Activism, and Ethnoracial Law and Policy in Latin America Jean Muteba Rahier Florida International University, US [email protected] This essay reviews the following works: Seams of Empire: Race and Radicalism in Puerto Rico and the United States. By Carlos Alamo-Pastrana. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2016. Pp. xvi + 213. $79.95 hardcover. ISBN: 9780813062563. Civil Rights and Beyond: African American and Latino/a Activism in the Twentieth-Century United States. Edited by Brian D. Behnken. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016. Pp. 270. $27.95 paperback. ISBN: 9780820349176. Afro-Politics and Civil Society in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. By Kwame Dixon. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2016. Pp. xiii + 174. $74.95 hardcover. ISBN: 9780813062617. Black Autonomy: Race, Gender, and Afro-Nicaraguan Activism. By Jennifer Goett. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2017. Pp. ix + 222. $26.00 paperback. ISBN: 9781503600546. The Politics of Blackness: Racial Identity and Political Behavior in Contemporary Brazil. By Gladys L. Mitchell-Walthour. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018. Pp. xvi + 266. $34.99 paperback. ISBN: 9781316637043. The Geographies of Social Movements: Afro-Colombian Mobilization and the Aquatic Space. By Ulrich Oslender. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016. Pp. xiii + 290. $25.95 paperback. ISBN: 9780822361220. Becoming Black Political Subjects: Movements and Ethno-Racial Rights in Colombia and Brazil. By Tianna S. Paschel. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism.