How New York Changes the Story of the Civil Rights Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Algebra Project Newsletter

December 15, 2020 NEWSLETTER Math Literacy | Is the Key | to 21st Century Citizenship! A student’s math Student voices his math literacy journey: Jevonnie literacy journey: I struggled through middle school. I barely made it to high school. The Jevonnie, p. 1 summer between 8th and 9th grade all athletes were required to be involved with the Young People’s Project Jevonnie, a high school senior (YPP) and the Algebra Project. I was really in Broward County, FL, shares not optimistic because it was doing math in the summer and all I wanted to do was his math literacy journey. work out and play football. But it was a totally different experience than what I Bob Moses & Henry envisioned it to be. The Algebra Project Hipps’ Fireside classroom when we started school was the Chat, link: p same. I was like, “oh, my gosh! I have math at 7:30 in the morning, every day.” Then I went and I was like… “wow this doesn’t feel The Algebra Project like a math class.” For the majority of the class you are not sitting down. in Broward County You are walking around, collaborating, talking with your friends, your peers, doing work with them. Ms. Caicedo is breaking things down. We Public Schools - would be so intrigued and involved in the lesson.… video highlights, p.2 As a YPP Math Literacy Worker (MLW) I got to see things outside of what my mind was always fixed on, which was sports. The kids came in Office of Academics: https:// and we started teaching them and I got to see the ‘mini-me’s’ – I got to www.browardschools.com/ see how I was in them. -

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in Mccomb, Mississippi, 1928-1964

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in McComb, Mississippi, 1928-1964 Alec Ramsay-Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 1, 2016 Advised by Professor Howard Brick For Dana Lynn Ramsay, I would not be here without your love and wisdom, And I miss you more every day. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... ii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: McComb and the Beginnings of Voter Registration .......................... 10 Chapter Two: SNCC and the 1961 McComb Voter Registration Drive .................. 45 Chapter Three: The Aftermath of the McComb Registration Drive ........................ 78 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 102 Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 119 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have done this without my twin sister Hunter Ramsay-Smith, who has been a constant source of support and would listen to me rant for hours about documents I would find or things I would learn in the course of my research for the McComb registration -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

The Making.Indd

PRIMARY SOURCE DOCUMENTARIES: The Making of “We’ll Never Turn Back” (1963) and “Dream Deferred” (1964) by Harvey Richards Written by Paul Richards, Ph.D. Photos by Harvey Richards In 1963 and 1964, my father, Harvey Richards, made two fi lms about the voter registration drives in Mississippi as part of the movement to end racial segregation in the United States. The fi lms are “We’ll Never Turn Back” (1963) and “Dream Deferred” (1964). They were a collaboration be- tween Harvey and Amzie Moore, a Cleveland, Mississippi resident and long time civil rights activist, designed to help organize and raise funds for the Student Non Violent Coor- dinating Committee (SNCC). The following is the story of how these fi lms were made. Late one February night in 1963, Harvey Richards drove his Oldsmobile station wagon full of sound and camera equip- ment, sporting a California license plate, up to the front door of Amzie Moore’s house in Cleveland, Mississippi. Cleve- land, Mississippi is a small delta town in the northern part of the state, about half a day’s drive from New Orleans, Loui- Harvey Richards (baseball cap) meeting with Amzie Moore (white overcoat) and (left to right) E.W.Steptoe, Bob Moses and unidentifi ed man. siana, where Harvey had spent the previous night. Amzie Moore opened his door and the two men, both 51 years old, met for the fi rst time. Harvey was around 6 foot tall, trim at 180 pounds, dressed in a warm canvas jacket and kaiki baseball cap. Amzie dressed in a plaid shirt and worn kaki pants, looked out his front door at this unannounced white stranger. -

W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies Undergraduate & Graduate Course Descriptions

W.E.B. DU BOIS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES UNDERGRADUATE & GRADUATE COURSE DESCRIPTIONS UNDERGRADUATE AFROAM 101. Introduction to Black Studies Interdisciplinary introduction to the basic concepts and literature in the disciplines covered by Black Studies. Includes history, the social sciences, and humanities as well as conceptual frameworks for investigation and analysis of Black history and culture. AFROAM 111. Survey African Art Major traditions in African art from prehistoric times to present. Allied disciplines of history and archaeology used to recover the early history of certain art cultures. The aesthetics in African art and the contributions they have made to the development of world art in modern times. (Gen.Ed. AT, G) AFROAM 113. African Diaspora Arts Visual expression in the Black Diaspora (United States, Caribbean, and Latin America) from the early slave era to the present. AFROAM 117. Survey of Afro-American Literature (4 credits) The major figures and themes in Afro-American literature, analyzing specific works in detail and surveying the early history of Afro-American literature. What the slave narratives, poetry, short stories, novels, drama, and folklore of the period reveal about the social, economic, psychological, and artistic lives of the writers and their characters, both male and female. Explores the conventions of each of these genres in the period under discussion to better understand the relation of the material to the dominant traditions of the time and the writers' particular contributions to their own art. (Gen.Ed. AL, U) (Planned for Fall) AFROAM 118. Survey of Afro-American Literature II (4 credits) Introductory level survey of Afro-American literature from the Harlem Renaissance to the present, including DuBois, Hughes, Hurston, Wright, Ellison, Baldwin, Walker, Morrison, Baraka and Lorde. -

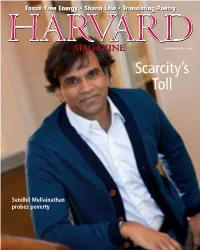

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

The Black Arts Movement Author(S): Larry Neal Source: the Drama Review: TDR, Vol

The Black Arts Movement Author(s): Larry Neal Source: The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 12, No. 4, Black Theatre (Summer, 1968), pp. 28-39 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1144377 Accessed: 13/08/2010 21:18 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Drama Review: TDR. http://www.jstor.org 29 The Black Arts Movement LARRYNEAL 1. The Black Arts Movement is radically opposed to any concept of the artist that al- ienates him from his community. -

ELLA BAKER, “ADDRESS at the HATTIESBURG FREEDOM DAY RALLY” (21 January 1964)

Voices of Democracy 11 (2016): 25-43 Orth 25 ELLA BAKER, “ADDRESS AT THE HATTIESBURG FREEDOM DAY RALLY” (21 January 1964) Nikki Orth The Pennsylvania State University Abstract: Ella Baker’s 1964 address in Hattiesburg reflected her approach to activism. In this speech, Baker emphasized that acquiring rights was not enough. Instead, she asserted that a comprehensive and lived experience of freedom was the ultimate goal. This essay examines how Baker broadened the very idea of “freedom” and how this expansive notion of freedom, alongside a more democratic approach to organizing, were necessary conditions for lasting social change that encompassed all humankind.1 Key Words: Ella Baker, civil rights movement, Mississippi, freedom, identity, rhetoric The storm clouds above Hattiesburg on January 21, 1964 presaged the social turbulence that was to follow the next day. During a mass meeting held on the eve of Freedom Day, an event staged to encourage African-Americans to vote, Ella Baker gave a speech reminding those in attendance of what was at stake on the following day: freedom itself. Although registering local African Americans was the goal of the event, Baker emphasized that voting rights were just part of the larger struggle against racial discrimination. Concentrating on voting rights or integration was not enough; instead, Baker sought a more sweeping social and political transformation. She was dedicated to fostering an activist identity among her listeners and aimed to inspire others to embrace the cause of freedom as an essential element of their identity and character. Baker’s approach to promoting civil rights activism represents a unique and instructive perspective on the rhetoric of that movement. -

Diversity in the Arts

Diversity In The Arts: The Past, Present, and Future of African American and Latino Museums, Dance Companies, and Theater Companies A Study by the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the University of Maryland September 2015 Authors’ Note Introduction The DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the In 1999, Crossroads Theatre Company won the Tony Award University of Maryland has worked since its founding at the for Outstanding Regional Theatre in the United States, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 2001 to first African American organization to earn this distinction. address one aspect of America’s racial divide: the disparity The acclaimed theater, based in New Brunswick, New between arts organizations of color and mainstream arts Jersey, had established a strong national artistic reputation organizations. (Please see Appendix A for a list of African and stood as a central component of the city’s cultural American and Latino organizations with which the Institute revitalization. has collaborated.) Through this work, the DeVos Institute staff has developed a deep and abiding respect for the artistry, That same year, however, financial difficulties forced the passion, and dedication of the artists of color who have theater to cancel several performances because it could not created their own organizations. Our hope is that this project pay for sets, costumes, or actors.1 By the following year, the will initiate action to ensure that the diverse and glorious quilt theater had amassed $2 million in debt, and its major funders that is the American arts ecology will be maintained for future speculated in the press about the organization’s viability.2 generations. -

Imperialism, Racism, and Fear of Democracy in Richard Ely's Progressivism

The Rot at the Heart of American Progressivism: Imperialism, Racism, and Fear of Democracy in Richard Ely's Progressivism Gerald Friedman Department of Economics University of Massachusetts at Amherst November 8, 2015 This is a sketch of my long overdue intellectual biography of Richard Ely. It has been way too long in the making and I have accumulated many more debts than I can acknowledge here. In particular, I am grateful to Katherine Auspitz, James Boyce, Bruce Laurie, Tami Ohler, and Jean-Christian Vinel, and seminar participants at Bard, Paris IV, Paris VII, and the Five College Social History Workshop. I am grateful for research assistance from Daniel McDonald. James Boyce suggested that if I really wanted to write this book then I would have done it already. And Debbie Jacobson encouraged me to prioritize so that I could get it done. 1 The Ely problem and the problem of American progressivism The problem of American Exceptionalism arose in the puzzle of the American progressive movement.1 In the wake of the Revolution, Civil War, Emancipation, and radical Reconstruction, no one would have characterized the United States as a conservative polity. The new Republican party took the United States through bloody war to establish a national government that distributed property to settlers, established a national fiat currency and banking system, a progressive income tax, extensive program of internal improvements and nationally- funded education, and enacted constitutional amendments establishing national citizenship and voting rights for all men, and the uncompensated emancipation of the slave with the abolition of a social system that had dominated a large part of the country.2 Nor were they done. -

Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin

Traut 1 Katerina Traut Lehigh University Giving ‘Substance to Freedom and Democracy’: Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin ABSTRACT: This paper explores labor organizer Vicki Garvin's life and ideas as an instantiation of Black feminism and as characterized by features central to contemporary Black feminist thought. Garvin's philosophy and practice of feminism come forth in her research and activism in worker’s rights, African American’s rights, and women’s rights. Garvin came of age in a post-WWII era of politics that was shaped by social movements toward liberation. As a demonstration of how to resist domination and oppression while remaining committed to the practice of democracy, Garvin's lifework deserves attention. INTRODUCTION According to Patricia Hill Collins, one distinguishing feature of Black feminist thought is that there is a dialectical relationship between oppression and activism, and there is a dialogical relationship between Black women's collective experiences of oppression and their group knowledge.1 Because of their unique position within the matrix of domination, defined as the social organization in which intersecting oppressions are developed, maintained, and maneuvered, African American women have a special knowledge about the interlocking nature of race, gender, and class oppression.2 Therefore, they must be a part of any effective effort to critique and overcome oppression. As Collins explains, this insight was known and practiced well before contemporary feminist thinkers such as herself conceptualized Black feminist thought as a particular field of scholarship. The research and activism of labor organizer Vicki Garvin demonstrates an understanding of the specific and important role that African American women (as one of many historically marginalized/oppressed groups) have to play within the Traut 2 institutional contexts that create and perpetuate their oppression.