Diversity in the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underserved Communities

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2016 Spring Grant Announcement Artistic Discipline/Field Listings Project details are accurate as of April 26, 2016. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Click the grant area or artistic field below to jump to that area of the document. 1. Art Works grants Arts Education Dance Design Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts 2. State & Regional Partnership Agreements 3. Research: Art Works 4. Our Town 5. Other Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Information is current as of April 26, 2016. Arts Education Number of Grants: 115 Total Dollar Amount: $3,585,000 826 Boston, Inc. (aka 826 Boston) $10,000 Roxbury, MA To support Young Authors Book Program, an in-school literary arts program. High school students from underserved communities will receive one-on-one instruction from trained writers who will help them write, edit, and polish their work, which will be published in a professionally designed book and provided free to students. Visiting authors, illustrators, and graphic designers will support the student writers and book design and 826 Boston staff will collaborate with teachers to develop a standards-based curriculum that meets students' needs. Abada-Capoeira San Francisco $10,000 San Francisco, CA To support a capoeira residency and performance program for students in San Francisco area schools. Students will learn capoeira, a traditional Afro-Brazilian art form that combines ritual, self-defense, acrobatics, and music in a rhythmic dialogue of the body, mind, and spirit. -

IMW Journal of Religious Studies Volume 8 Number 1

Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies Volume 8 Number 1 Fall 2017 Article 6 2017 IMW Journal of Religious Studies Volume 8 Number 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal Recommended Citation "IMW Journal of Religious Studies Volume 8 Number 1." Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 8, no. 1 (2017). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol8/iss1/6 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 8 Number 1 Winter 2017 The Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies is designed to promote the academic study of religion at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The journal is a student initiative affiliated with the Religious Studies Program and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Utah State University. Our academic review board includes professional scholars specializing in Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Mormonism, as well as specialists in the fields of History, Philosophy, Psychology, Anthropology, Sociology, and Religion. The journal is housed in the Intermountain West, but gladly accepts submissions from students throughout the United States and around the world. INTERMOUNTAIN WEST JOURNAL OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES Philip Barlow ADVISOR Ravi Gupta ADVISOR Christine Blythe EDITOR Bob Call ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emily Farnsworth ASSOCIATE EDITOR Adam Gifford ASSOCIATE EDITOR Colby Townsend ASSOCIATE EDITOR Logan Broadbent BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Mark Rasmuson JOURNAL DESIGN ACADEMIC REVIEW BOARD Debra Baldwin Utah State University Philip Barlow Utah State University Christopher Blythe Joseph Smith Papers Jeff Cannon University of Edinburgh John Crow Florida State University Matthew Goff Florida State University Ravi Gupta Utah State University Brian Hauglid Brigham Young University Patrick Q. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Black History Month February 2020

BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 LITERARY FINE ARTS MUSIC ARTS Esperanza Rising by Frida Kahlo Pam Munoz Ryan Frida Kahlo and Her (grades 3 - 8) Animalitos by Monica Brown and John Parra What Can a Citizen Do? by Dave Eggers and Shawn Harris (K-2) MATH & CULINARY HISTORY SCIENCE ARTS BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 FINE ARTS Alma Thomas Jacob Lawrence Faith Ringgold Alma Thomas was an Faith Ringgold works in a Expressionist painter who variety of mediums, but is most famous for her is best-known for her brightly colored, often narrative quilts. Create a geometric abstract colorful picture, leaving paintings composed of 1 or 2 inches empty along small lines and dot-like the edge of your paper marks. on all four sides. Cut colorful cardstock or Using Q-Tips and primary Jacob Lawrence created construction paper into colors, create a painted works of "dynamic squares to add a "quilt" pattern in the style of Cubism" inspired by the trim border to your Thomas. shapes and colors of piece. Harlem. His artwork told stories of the African- American experience in the 20th century, which defines him as an artist of social realism, or artwork based on real, modern life. Using oil pastels and block shapes, create a picture from a day in your life at school. What details stand out? BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 MUSIC Creating a Music important to blues music, and pop to create and often feature timeless radio hits. Map melancholy tales. Famous Famous Motown With your students, fill blues musicians include B.B. -

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

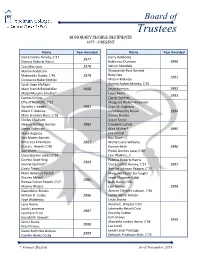

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Our Firm Foundation, Our Refuge, and Our Deliverer Our Firm Foundation, Our Refuge, Amd Our Deliverer

Fall 2018 Orthodox Church in America • Diocese of New York and New Jersey Our Firm Foundation, Our Refuge, and Our Deliverer Our Firm Foundation, Our Refuge, amd Our Deliverer ............3 Making the Gospel Good News Again ............................................4 No Other Foundation: Building an Orthodox Parish ...............7 Ancient Foundations and New Beginnings .................................8 “For the Life of the World”: On the AAC in St. Louis ................11 2018: A Year of Joy and Sadness at Holy Resurrection Church, Wayne .............................................................................Table of Contents11 Youth at the AAC ................................................................................12 OurTheme Diocese and the Orthodox Church in Slovakia ..................13 “GiveFall me this 2018 water, that I may not thirst . .” An Iconographic Journey ................................................................14 John 4:15 What’s Going on in Oneonta ..........................................................17 Celebrating Father Paul and Matushka Mary Shafran .............18 In Memoriam: Fr. Stephen Mack ....................................................20 DiocesanIn Memoriam: Fr. Life John Nehrebecki ...............................................22 St. Olympia Mission - Potsdam, NY ...............................................23 Published with the St. Simon Mission Parish’s Outreach to the Blessing of His Eminence, African-American Community .................................................25 -

W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies Undergraduate & Graduate Course Descriptions

W.E.B. DU BOIS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES UNDERGRADUATE & GRADUATE COURSE DESCRIPTIONS UNDERGRADUATE AFROAM 101. Introduction to Black Studies Interdisciplinary introduction to the basic concepts and literature in the disciplines covered by Black Studies. Includes history, the social sciences, and humanities as well as conceptual frameworks for investigation and analysis of Black history and culture. AFROAM 111. Survey African Art Major traditions in African art from prehistoric times to present. Allied disciplines of history and archaeology used to recover the early history of certain art cultures. The aesthetics in African art and the contributions they have made to the development of world art in modern times. (Gen.Ed. AT, G) AFROAM 113. African Diaspora Arts Visual expression in the Black Diaspora (United States, Caribbean, and Latin America) from the early slave era to the present. AFROAM 117. Survey of Afro-American Literature (4 credits) The major figures and themes in Afro-American literature, analyzing specific works in detail and surveying the early history of Afro-American literature. What the slave narratives, poetry, short stories, novels, drama, and folklore of the period reveal about the social, economic, psychological, and artistic lives of the writers and their characters, both male and female. Explores the conventions of each of these genres in the period under discussion to better understand the relation of the material to the dominant traditions of the time and the writers' particular contributions to their own art. (Gen.Ed. AL, U) (Planned for Fall) AFROAM 118. Survey of Afro-American Literature II (4 credits) Introductory level survey of Afro-American literature from the Harlem Renaissance to the present, including DuBois, Hughes, Hurston, Wright, Ellison, Baldwin, Walker, Morrison, Baraka and Lorde. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1982

Nat]onal Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1982. Respectfully, F. S. M. Hodsoll Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. March 1983 Contents Chairman’s Statement 3 The Agency and Its Functions 6 The National Council on the Arts 7 Programs 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 30 Expansion Arts 46 Folk Arts 70 Inter-Arts 82 International 96 Literature 98 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 114 Museum 132 Music 160 Opera-Musical Theater 200 Theater 210 Visual Arts 230 Policy, Planning and Research 252 Challenge Grants 254 Endowment Fellows 259 Research 261 Special Constituencies 262 Office for Partnership 264 Artists in Education 266 State Programs 272 Financial Summary 277 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 278 The descriptions of the 5,090 grants listed in this matching grants, advocacy, and information. In 1982 Annual Report represent a rich variety of terms of public funding, we are complemented at artistic creativity taking place throughout the the state and local levels by state and local arts country. These grants testify to the central impor agencies. tance of the arts in American life and to the TheEndowment’s1982budgetwas$143million. fundamental fact that the arts ate alive and, in State appropriations from 50 states and six special many cases, flourishing, jurisdictions aggregated $120 million--an 8.9 per The diversity of artistic activity in America is cent gain over state appropriations for FY 81. -

Nytimes Black History Month Is a Good Excuse for Delving Into Our

Black History Month Is a Good Excuse for Delving Into Our Art An African-American studies professor suggests ways to mark the month, from David Driskell’s paintings and Dance Theater of Harlem’s streamed performances to the rollicking return of “Queen Sugar.” David Driskell’s “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” (1972), acrylic on canvas. Estate of David C. Driskell and DC Moore Gallery By Salamishah Tillet • Feb. 18, 2021 Black History Month feels more urgent this year. Its roots go back to 1926, when the historian Carter G. Woodson developed Negro History Week, near the February birthdays of both President Abraham Lincoln and the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, in the belief that new stories of Black life could counter old racist stereotypes. Now in this age of racial reckoning and social distancing, our need to connect with each other has never been greater. As a professor of African-American studies, I am increasingly animated by the work of teachers who have updated Woodson’s goal for the 21st century. Just this week, my 8- year-old daughter showed me a letter written by her entire 3rd-grade art class to Faith Ringgold, the 90-year-old African-American artist. And my son told me about a recent pre-K lesson on Ruby Bridges, the first African-American student who, at 6, integrated an elementary school in the South. Suddenly, the conversations my kids have at home with my husband and me are the ones they’re having in their classrooms. It's not just their history that belongs in all these spaces, but their knowledge, too. -

The Black Arts Movement Author(S): Larry Neal Source: the Drama Review: TDR, Vol

The Black Arts Movement Author(s): Larry Neal Source: The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 12, No. 4, Black Theatre (Summer, 1968), pp. 28-39 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1144377 Accessed: 13/08/2010 21:18 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Drama Review: TDR. http://www.jstor.org 29 The Black Arts Movement LARRYNEAL 1. The Black Arts Movement is radically opposed to any concept of the artist that al- ienates him from his community. -

Access to Funding Crucial for Countries the Ability of a Country Amor Mottley Reiterated Underlining the Impact Ready Reeling

Established October 1895 Schools undergoing clean up Page 2 Friday May 29, 2020 $2 VAT Inclusive ALL RETAIL STORES Public warned, ‘Social distancing protocols still in place’ TOAS of Monday June 1st, REOPEN all remaining retail businesses will be al- lowed to reopen and conduct business. This was announced by Attorney General Dale Marshall yesterday evening at a press confer- ence at the Lloyd Erskine Sandiford Centre. However, with June 1st being Whit Monday and a bank holiday, the full ef- fect of the further reopen- ing of Barbados will be felt next Tuesday,when all re- tail stores are cleared to reopen and curfew hours reduced. The new lock- down hours will be from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. on Mondays to Thursdays, and from 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. on Fridays to Sundays. The alphabet system for retail entities, supermar- kets and banking institu- tions will also be discon- tinued, come Monday. Services such as photo studios, real estate agents, car rentals, animal groom- ing, trucking and trans- port of goods, storage, car valet, well cleaning and re- cycling will be allowed to operate as of June 1st. Churches and other faith- based entities will be happy to hear that they also will be allowed to con- duct services with mem- bers in attendance, with The top officials were present during announcements made last night, regarding the COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery Plan. (From left) Lt the established health Col Hon Jeffery Bostic, Minister of Health and Wellness, Senior Economic Advisor Dr Kevin Greenidge, Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley, REOPEN on Page 3 Attorney-General Dale Marshall and Richard Carter, COVID-19 Czar.