IMW Journal of Religious Studies Volume 8 Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Firm Foundation, Our Refuge, and Our Deliverer Our Firm Foundation, Our Refuge, Amd Our Deliverer

Fall 2018 Orthodox Church in America • Diocese of New York and New Jersey Our Firm Foundation, Our Refuge, and Our Deliverer Our Firm Foundation, Our Refuge, amd Our Deliverer ............3 Making the Gospel Good News Again ............................................4 No Other Foundation: Building an Orthodox Parish ...............7 Ancient Foundations and New Beginnings .................................8 “For the Life of the World”: On the AAC in St. Louis ................11 2018: A Year of Joy and Sadness at Holy Resurrection Church, Wayne .............................................................................Table of Contents11 Youth at the AAC ................................................................................12 OurTheme Diocese and the Orthodox Church in Slovakia ..................13 “GiveFall me this 2018 water, that I may not thirst . .” An Iconographic Journey ................................................................14 John 4:15 What’s Going on in Oneonta ..........................................................17 Celebrating Father Paul and Matushka Mary Shafran .............18 In Memoriam: Fr. Stephen Mack ....................................................20 DiocesanIn Memoriam: Fr. Life John Nehrebecki ...............................................22 St. Olympia Mission - Potsdam, NY ...............................................23 Published with the St. Simon Mission Parish’s Outreach to the Blessing of His Eminence, African-American Community .................................................25 -

Access to Funding Crucial for Countries the Ability of a Country Amor Mottley Reiterated Underlining the Impact Ready Reeling

Established October 1895 Schools undergoing clean up Page 2 Friday May 29, 2020 $2 VAT Inclusive ALL RETAIL STORES Public warned, ‘Social distancing protocols still in place’ TOAS of Monday June 1st, REOPEN all remaining retail businesses will be al- lowed to reopen and conduct business. This was announced by Attorney General Dale Marshall yesterday evening at a press confer- ence at the Lloyd Erskine Sandiford Centre. However, with June 1st being Whit Monday and a bank holiday, the full ef- fect of the further reopen- ing of Barbados will be felt next Tuesday,when all re- tail stores are cleared to reopen and curfew hours reduced. The new lock- down hours will be from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. on Mondays to Thursdays, and from 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. on Fridays to Sundays. The alphabet system for retail entities, supermar- kets and banking institu- tions will also be discon- tinued, come Monday. Services such as photo studios, real estate agents, car rentals, animal groom- ing, trucking and trans- port of goods, storage, car valet, well cleaning and re- cycling will be allowed to operate as of June 1st. Churches and other faith- based entities will be happy to hear that they also will be allowed to con- duct services with mem- bers in attendance, with The top officials were present during announcements made last night, regarding the COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery Plan. (From left) Lt the established health Col Hon Jeffery Bostic, Minister of Health and Wellness, Senior Economic Advisor Dr Kevin Greenidge, Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley, REOPEN on Page 3 Attorney-General Dale Marshall and Richard Carter, COVID-19 Czar. -

1998 Acquisitions

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in. -

Diversity in the Arts

Diversity In The Arts: The Past, Present, and Future of African American and Latino Museums, Dance Companies, and Theater Companies A Study by the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the University of Maryland September 2015 Authors’ Note Introduction The DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the In 1999, Crossroads Theatre Company won the Tony Award University of Maryland has worked since its founding at the for Outstanding Regional Theatre in the United States, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 2001 to first African American organization to earn this distinction. address one aspect of America’s racial divide: the disparity The acclaimed theater, based in New Brunswick, New between arts organizations of color and mainstream arts Jersey, had established a strong national artistic reputation organizations. (Please see Appendix A for a list of African and stood as a central component of the city’s cultural American and Latino organizations with which the Institute revitalization. has collaborated.) Through this work, the DeVos Institute staff has developed a deep and abiding respect for the artistry, That same year, however, financial difficulties forced the passion, and dedication of the artists of color who have theater to cancel several performances because it could not created their own organizations. Our hope is that this project pay for sets, costumes, or actors.1 By the following year, the will initiate action to ensure that the diverse and glorious quilt theater had amassed $2 million in debt, and its major funders that is the American arts ecology will be maintained for future speculated in the press about the organization’s viability.2 generations. -

Methodists in Search of Unity Amidst Division

Methodists in Search of Unity amidst Division: Considering the Values and Costs of Unity and Separation in the Face of Two Moral Crises: Slavery and Sexual Orientation [Presented at the Oxford Institute for Methodist Studies, August 2007.] By Bruce W. Robbins [Author’s Note: This paper will undergo revision in the fall of 2007. The revised copy will be posted on the Oxford Institute website when completed.] Introduction For the last decade and more, The United Methodist Church (UMC) has been facing conflict caused by contrasting views of a moral issue: whether or not persons who are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Transgender (LGBT)1 should be welcomed as others into the UMC as lay members or as clergy. The debate has been distressing to all in the church , for many because it has prevented debate and action on many of the other issues associated with Christian ministry. During the last four years, the debate has evolved into intense discussion of ecclesiological issues and has led some members to question the value of maintaining unity within the UMC, or to wonder whether it would be better and, perhaps, more faithful to separate into different institutional structures. Nearly two centuries ago, the church faced another major divide over a moral issue- slavery. Alongside many differences between the two historical contexts, there are also similarities that church members faced, similarities that can be seen through the debates and actions within the annual and general conferences of the church. The slavery debates in the 1830s and 40s culminated in several splits in Methodism, the largest of which, in 1844, saw no reunion until ninety-five years had passed. -

Gay Austin ______Gallup Polls Teens on Gays

free! summer 1979 vol. 3 , no. 9 Verdict against Driskill Gay victory rn• court J,,'IJJTOR'.'i SOTF.'. As this issu, oj Math, u Cole.,, the qa!I rigl.ts actin st (;ay Austin u·as qmnq 1,, pri .,s. thf' from Sari Fm, cisco ,m hand 111 .4ustm Ca/mr.-t disco 11,,s found guilty of twlat• for th, lrinl, ca/1,•d th, ens, the first ,,,- 1l.1 kind in th, rmrnlr1/ u ·h,r1 th, ts s11e 111.Q lht nt11 s ord/nm,cc and fi,u d $200. Th, m uuirtpal court Jury rmnposed of of" thscn m uullion ro11~rr1u d a person\ ·" ;ru,,I pr,/1 rt nc,• thr,,,, tronu·u (111d thret men took fr.1ts Ihm, half"" h1111r to ri·arh its 1·,-rdict lJrt•k1/I atlor111 y Mark L, 1·barg said that //1, d1srn ·s h1111.si rul1 aqain.,t same hi 11·011/d u , k 11 11 app1 al ,m th, grounds that the ordwrrnce ts ""lmJ mgue tu ~, J da11n11q 11ofoff.s th, ..pubh r ucrom • mmlotious .. urdi11nt1n. t'U/orn . " Thi· romplaint against the Cabaret bar nances in other cities, was scheduled to nt th,• Driskill Hotel for discriminating come lo Austin in June for the trial. against patrons on the basis of sexual Coles is primarily concerned with oriental ion 1s 1•xp1·rl!•d to tw heard in defending the ordinance from any con Celebrants on Town Lake tor all-day festivities May 26. mumripnl ,·uurt Jul} 10. •titutional challenges, such as the Thi• spc·r1f1t· s,•tt1ng oft h1• trial is st ill Cabaret's injunction pt'ndmg," explained Woody Egger, who "This is one of the first test casf's of has clos1•ly monitored the complaint's surh an ordinance anywhere." Egger Marchers convene progress. -

WE REMEMBER the PROPHETIC WORDS of DR MARTIN LUTHER KING JR BEACON, January 14 – January 20, 2021 Newyorkbeacon.Com 2 C T 29, 2020, a Spokesperson for Jacob Blake

“Arming Black Millennials the New York With Information" ELECTION 2020: “Arming Black Millennials with Information" 75 Cents Vol. 28 No. 2 January 14 – January 20, 2021 website: NewYorkBeacon.com AS DR KING CELEBRATIONS ARE HELD VIRTUALLY ACROSS THE NATION Image source: Herlanzer/ Milan M/Shutterstock/Big Think WE REMEMBER THE PROPHETIC WORDS OF DR MARTIN LUTHER KING JR 2 Trump golf course Twitter bans President stripped of 2022 US PGA Newyorkbeacon.com continue to lead and grow our Trump permanently game for decades to come.” By Joséphine Li rump National in The course in New Jersey, New York Beacon writer Bedminster has been one of 17 courses around the stripped of the US PGA world owned by Trump, was ate Friday evening, Twit- TChampionship in 2022 as its due to host the major in May ter said that after a close organisers felt using the course 2022. review of recent tweets as host would be “detrimen- Another of his properties, Lfrom the president’s account, tal”. Trump Turnberry in Ayrshire, it had suspended President The PGA of America voted Scotland, has not been selected Trump from its platform due to terminate the agreement on to host an Open Champion- to the risk of further incitement Sunday. ship by the R&A since Trump of violence. US President Donald bought the resort in 2014 – Twitter issued a statement Trump, who owns the course, with the host venues now last Wednesday warning has been accused by Demo- finalised up to 2024. Trump that additional viola- crats and some Republicans of Turnberry’s Ailsa course tions of Twitter’s rules would encouraging last Wednesday’s has hosted The Open on four potentially lead to a ban. -

January 2004

Non-Profit Organization Please share this Newsletter with your colleagues and circulate among organization staff. U.S. Postage Paid Call for Papers for Symposium 26 in Detroit on page 27. Akron, OH Permit Number 222 Association for the Advancement of Social Work with Groups, Inc. An International Professional Organization c/o The University of Akron Akron, OH 44325-8050 U.S.A. ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED SOCIAL WORK WITH GROUPS NEWSLETTER Current News and Cumulative Reference. ISSN 1084-6816 Advocacy and Action in Support of Group Work Practice, Education, Research, and Publication. Enhancing the Quality of Group Life throughout the World. Published at the University of Akron School of Social Work by the Association for the Advancement of Social Work with Groups, Inc., An International Professional Organization. Vol. 19, #3, Issue #52 January 2004 THE PRESIDENT'S PEN SAVE THE DATES NOW WELCOME ABELS A Partial View JOIN YOUR AS NEW PRESIDENT, Paul Abels, President COLLEAGUES ANDREWS AS Florence Kelly, who had worked at Hull House and later became head of the OCTOBER 21-24 VICE PRESIDENT, AND National Consumer's League, once said, IN DETROIT ALVAREZ, GALINSKY, "You know at twenty I signed up to serve SPELTERS AT LARGE my country for the duration of the war on The theme of the 26th International poverty and on injustice and on oppres- Symposium is "Group Work Reaching After finishing his undergraduate sion and I take it...that it will last out my across Boundaries: Disciplines, Practice degree at Rutgers as a Psychology major, life and yours and our children's lives." Settings, Seasons of Life, Cultures and our new President, Paul A. -

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches A

Atlas cover:Layout 1 4/19/11 11:08 PM Page 1 Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches Assembling a mass of recently generated data, the Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches provides an authoritative overview of a most important but often neglected segment of the American Christian community. Protestant and Catholic Christians especially will value editor Alexei Krindatchʼs survey of both Eastern Orthodoxy as a whole and its multiple denominational expressions. J. Gordon Melton Distinguished Professor of American Religious History Baylor University, Waco, Texas Why are pictures worth a thousand words? Because they engage multiple senses and ways of knowing that stretch and deepen our understanding. Good pictures also tell compelling stories. Good maps are good pictures, and this makes the Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches, with its alternation and synthesis of picture and story, a persuasive way of presenting a rich historical journey of Orthodox Christianity on American soil. The telling is persuasive for both scholars and adherents. It is also provocative and suggestive for the American public as we continue to struggle with two issues, in particular, that have been at the center of the Orthodox experience in the United States: how to create and maintain unity across vast terrains of cultural and ethnic difference; and how to negotiate American culture as a religious other without losing oneʼs soul. David Roozen, Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research Hartford Seminary Orthodox Christianity in America has been both visible and invisible for more than 200 years. Visible to its neighbors, but usually not well understood; invisible, especially among demographers, sociologists, and students of American religious life. -

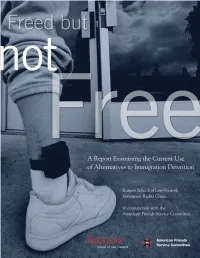

Freed-But-Not-Free.Pdf

Authors & Acknowledgements A. ORGANIZATIONS a. Rutgers School of Law–Newark Immigrant Rights Clinic The Clinical Program at Rutgers School of Law–Newark is designed to provide law students the opportunity to work on actual cases and projects and to learn essential lawyering skills, substantive and procedural law, professional values, and applied legal ethics. The program is one of few free legal service providers in New Jersey. All of the legal clinics help fill large voids in service coverage for low-income and underrepresented persons and communities throughout Newark and the greater New Jersey area. Launched in January 2012, the Immigrant Rights Clinic (IRC) at Rutgers School of Law–Newark serves the local and national immigrant population through a combination of individual client representation and broader advocacy projects. Under the supervision of Professor Anjum Gupta, students in the IRC represent immigrants seeking various forms of relief from removal, including asylum; withholding of removal; relief under the Convention Against Torture; protection for victims of human trafficking; protection for battered immigrants; protection for victims of certain types of crimes; protection for abused, abandoned, or neglected immigrant children; and cancellation of removal. Students also engage in broader advocacy projects on behalf of organizational clients, primarily immigrant rights organizations. This report is the result of one such project. Working under the supervision of Professor Gupta, and on behalf of the American Friends Service Committee, the following law students assumed primary responsibility for the production of this report: Nicole D. Finnie, Roman Guzik, and Jennifer J. Pinales. b. American Friends Service Committee Immigrant Rights Program The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Quaker organization that has worked for over 90 years to uphold human dignity and respect for the rights of all persons. -

Paul Abels Ev

Telling Our Stories 250 Years of United Methodism in the New York Area 1766-2016 www.nyac.com/250years Social Activist, Musician, and First Openly Gay Pastor in the NYAC 1937-1992 Image courtesy of the General Commission on Archives and History Paul Abels ev. Paul Abels lived a life of integrity, courage, and faith with a “million dollar smile.” He worked for social justice, For Discussion Rpursued his love of the arts, music and historical preservation, and challenged the church to open its doors to the diverse con- cerns of the gay and lesbian community. • In his role as pastor, Abels was well-re- During his pastorate at Washington Square UMC (known as spected for his social activism and work in the “Peace Church”), he nurtured community organizations the arts. How important is it for pastors to and oversaw an extensive building restoration campaign. He be leaders both in the church and in the also began performing “covenant ceremonies” for gay and les- community? bian members of his congregation. • Society’s attitudes toward the LGBTQ Controversy ensued when he publicly acknowledged his ho- community have changed significantly mosexuality in 1977. He was urged to take a leave but declined, in the last few years. Within the UMC, and both NYAC and the Judicial Council upheld his appoint- debate continues regarding its policies on ment. In 1984 he retired, the same year that General Confer- same-sex marriage, openly gay pastors, ence voted to bar actively gay men and women from ordina- and other LGBTQ issues. How would you tion and serving as clergy. -

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches A

Atlas cover:Layout 1 4/19/11 11:08 PM Page 1 A t l Assembling a mass of recently generated data, the Atlas of American Orthodox a s Christian Churches provides an authoritative overview of a most important but o often neglected segment of the American Christian community. Protestant and f Catholic Christians especially will value editor Alexei Krindatchʼs survey of both A Eastern Orthodoxy as a whole and its multiple denominational expressions. m J. Gordon Melton e Distinguished Professor of American Religious History r i Baylor University, Waco, Texas c a n Why are pictures worth a thousand words? Because they engage multiple senses O and ways of knowing that stretch and deepen our understanding. Good pictures r t also tell compelling stories. Good maps are good pictures, and this makes the h Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches , with its alternation and synthesis o of picture and story, a persuasive way of presenting a rich historical journey of d Orthodox Christianity on American soil. The telling is persuasive for both scholars o and adherents. It is also provocative and suggestive for the American public as x we continue to struggle with two issues, in particular, that have been at the center C of the Orthodox experience in the United States: how to create and maintain unity h r across vast terrains of cultural and ethnic difference; and how to negotiate i s American culture as a religious other without losing oneʼs soul. t i David Roozen , Director a Hartford Institute for Religion Research n Hartford Seminary C h u r Orthodox Christianity in America has been both visible and invisible for more than c 200 years.