FALL 2007 VOLUME 24:2 Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy

The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy Dr. Valerie Scatamburlo-D'Annibale University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada Abstract This article explores how Donald Trump capitalized on the right's decades-long, carefully choreographed and well-financed campaign against political correctness in relation to the broader strategy of 'cultural conservatism.' It provides an historical overview of various iterations of this campaign, discusses the mainstream media's complicity in promulgating conservative talking points about higher education at the height of the 1990s 'culture wars,' examines the reconfigured anti- PC/pro-free speech crusade of recent years, its contemporary currency in the Trump era and the implications for academia and educational policy. Keywords: political correctness, culture wars, free speech, cultural conservatism, critical pedagogy Introduction More than two years after Donald Trump's ascendancy to the White House, post-mortems of the 2016 American election continue to explore the factors that propelled him to office. Some have pointed to the spread of right-wing populism in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis that culminated in Brexit in Europe and Trump's victory (Kagarlitsky, 2017; Tufts & Thomas, 2017) while Fuchs (2018) lays bare the deleterious role of social media in facilitating the rise of authoritarianism in the U.S. and elsewhere. Other 69 | P a g e The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy explanations refer to deep-rooted misogyny that worked against Hillary Clinton (Wilz, 2016), a backlash against Barack Obama, sedimented racism and the demonization of diversity as a public good (Major, Blodorn and Blascovich, 2016; Shafer, 2017). -

Lgi Newsletter 2017

LGI NEWSLETTER 2017 BENEFIT On September 27th, a benefit to raise money for scholarships to the LGI was held at the home of Kevin Breslin (L73) Professor John Van Sickle of Brooklyn College. Thomas Bruno (G95) Hors d’oeuvres were furnished by M.J. Amy Bush (G93) McNamara (G01), a chef as well as a Ph.D. Rowland Butler (L87) student in classics at The Graduate Center. She Jeffrey Cassvan (L92) explained her choices of food and how she tried Donovan Chaney (G99) to approximate the ingredients the Romans Amy Cooper (G12) used. Dr. Alex Conison, the Brand Manager of Susan Crane (L97) Josh Cellars at Deutsch Family Wine & Spirits, Michael Degener (G84) did his Ph. D. dissertation on Roman wine and Nicholas de Peyster (G85) supplied the wine and explained how it Jeanne Detch (G93) compared with the wines the Romans drank. Joan Esposito (G86) There was a mixture of classicists and non- Michael Esposito (G08) classicists and conversations flowed till late in Isabel Farias (G12) the evening. It was a most successful event. Alison Fields (L07) Earlier in the year, we held a different event for Jeff Fletcher (L88) the same purpose. This was a lecture in lower Thomas Frei (G83) Manhattan followed by a reception. The Robert Frumkin (L82) speaker was Joy Connolly, Provost and John Fulco (L75) Professor of Classics at The CUNY Graduate Peggy Fuller (L85) Center. Her topic was, “Why Autocracy Robert Gabriele (G12) Appeals: Lessons from Roman Epic,” a timely John Gedrick (L90) reflection on the lessons that Lucan’s Pharsalia Richard Giambrone (G81, L82) offers to our current political situation. -

Download the Complete Issue PDF 550 KB

Media Watch ... 9 September 2019 Edition | Issue # 630 is intended as an advocacy, re- search and teaching tool. The weekly report is international in scope and distribution – to col- leagues who are active or have a special interest in hospice and palliative care , and in the quality of end-of-life care in general – to help keep them abreast of current, emerging and related issues – Compilation of Media Watch 2008 -2019 © and, to inform discussion and en- courage further inquiry. Compiled & Annotated by Barry R. As hpole Nearly one-third of children’s hospitals [in the U.S.] do not have formalized palliative care service and advance care discussions tend to occur during relapses and treatment failures rather then at initial diagnosis. ‘Lack of equality in end-of-life care for children ’ (p.11), Pediatric Critical Care Medicine , 2019;20(9):897 -898. Canada Cancer overtakes heart disease as biggest killer in wealthy countries CBC NEWS | Online – 3 September 2019 – million were due to cardiovascular disease – a Cancer has overtaken heart disease as the lea d- group of conditions that includes heart failure, ing cause of death in wealthy count ries and angina, heart attack and stro ke. Countries ana- could become the world’ s biggest killer within lyzed included Argentina, Bangladesh, Br a- just a few decades if current tre nds perspersist... zil, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, India, Iran, Publishing the findings of two large studies … Malaysia, Pakistan, Palestine, Philippines, Po l- scientists said they showed evi dence of a new and, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Sweden, Ta n- global “epidemiologic transition” between diffe r- zania, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Zi m- ent types of chronic disease. -

Unmasking the Oregon Klansman: the Ku Klux Klan in Astoria 1921-1925

Unmasking the Oregon Klansman: The Ku Klux Klan in Astoria 1921-1925 Annie McLain 2003 I. Introduction “Carry on Knights of the Ku Klux Klan! Carry on until you have made it impossible for citizens of foreign birth, of Jewish blood or of Catholic faith to serve their community or their country in any capacity, save as taxpayers.” [1] On January 30, 1922 the Astoria Daily Budget ran an editorial responding to the racial and religious tension in Astoria created by the Ku Klux Klan. The staff of the Daily Budget joined local Catholics and immigrants in an attack against the organization they believed was responsible for the factional strife and political discord that characterized their city. While the editor attacked the Klan, one local minister praised the organization by saying, “I can merely say that I have a deep feeling in my heart for the Klansmen . and that I am proud that men of the type these have proven themselves to be are in an organized effort to perpetuate true Americanism,” [2] The minister clearly believed the Klan would lead the city toward moral reform and patriotic unity. Both the editor and the minister were describing the same organization but their conflicting language raises some important questions. The tension between these two passages reveals the social and political climate of Astoria in the early part of the 1920s. Astorians believed their city was in need of reform at the end of World War I. Their economy was in a slump, moral vice invaded the city and political corruption was rampant. -

Gender, Identity Framing, and the Rhetoric of the Kill in Conservative Hate Mail

Communication, Culture & Critique ISSN 1753-9129 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Foiling the Intellectuals: Gender, Identity Framing, and the Rhetoric of the Kill in Conservative Hate Mail Dana L. Cloud Department of Communication Studies, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712, USA This article introduces the concept of identity framing by foil. Characteristics of this communicative mechanism are drawn from analysis of my personal archive of conservative hate mail. I identify 3 key adversarial identity frames attributed to me in the correspondence: elitist intellectual, national traitor, and gender traitor. These identity frames serve as foils against which the authors’ letters articulate identities as real men and patriots. These examples demonstrate how foiling one’s adversary relies on the power of naming; applies tremendous pressure to the target through identification and invocation of vulnerabilities; and employs tone and verbal aggression in what Burke identified as ‘‘the kill’’: the definition of self through the symbolic purgation and/or negation of another. doi:10.1111/j.1753-9137.2009.01048.x I was deluged with so much hate mail, but none of it was political ....It was like, ‘‘Gook, chink, cunt. Go back to your country, go back to your country where you came from, you fat pig. Go back to your country you fat pig, you fat dyke. Go back to your country, fat dyke. Fat dyke fat dyke fat dyke—Jesus saves.’’—Margaret Cho, ‘‘Hate Mail From Bush Supporters’’ (2004) My question to you. If you was [sic] a professor in Saudi Arabia, North Korea, Palestinian university or even in Russia. etc. How long do you think you would last as a living person regarding your anti government rhetoric in those countries? We have a saying referring to people like you. -

Leading the Walking Dead: Portrayals of Power and Authority

LEADING THE WALKING DEAD: PORTRAYALS OF POWER AND AUTHORITY IN THE POST-APOCALYPTIC TELEVISION SHOW by Laura Hudgens A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at Middle Tennessee State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Mass Communication August 2016 Thesis Committee: Dr. Katherine Foss, Chair Dr. Jane Marcellus Dr. Jason Reineke ii ABSTRACT This multi-method analysis examines how power and authority are portrayed through the characters in The Walking Dead. Five seasons of the show were analyzed to determine the characteristics of those in power. Dialogue is important in understanding how the leaders came to power and how they interact with the people in the group who have no authority. The physical characteristics of the leaders were also examined to better understand who was likely to be in a position of power. In the episodes in the sample, leaders fit into a specific demographic. Most who are portrayed as having authority over the others are Caucasian, middle-aged men, though other characters often show equivalent leadership potential. Women are depicted as incompetent leaders and vulnerable, and traditional gender roles are largely maintained. Findings show that male conformity was most prevalent overall, though instances did decrease over the course of five seasons. Instances of female nonconformity increased over time, while female conformity and male nonconformity remained relatively level throughout. ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ..............................................................................................................v -

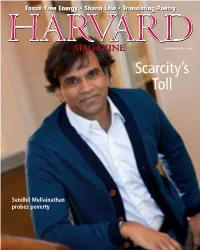

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

A Visual Exploration Into the American Debate on Reparations

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2020 Repairing a Nation: A visual exploration into the American debate on reparations Desi Jeseve LaPoole The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the African American Studies Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Film Production Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation LaPoole, Desi Jeseve, "Repairing a Nation: A visual exploration into the American debate on reparations" (2020). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8884. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2020 Desi Jeseve LaPoole REPAIRING A NATION: A VISUAL EXPLORATION INTO THE AMERICAN DEBATE ON REPARATIONS FOR SLAVERY by Desi LaPoole An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study in Journalism and Society March 25, 2020 Advisor: Dr. Denise Bostdorff Abstract The debate on reparations for slavery in the United States of America has persisted for generations, capturing the attention and imagination of America in waves before falling out of public consciousness over the decades. Throughout its longevity, the debate on reparations has had many arguments in support of and opposition towards the idea and has inspired many different proposals which seek to solve many different problems. Today, reparations have found new mainstream attention, thanks in part Ta-Nehisi Coates’ article, “The Case for Reparations,” published in The Atlantic, and to two new reparations bills in Congress. -

Behind the Scenes: Uncovering Violence, Gender, and Powerful Pedagogy

Behind the Scenes: Uncovering Violence, Gender, and Powerful Pedagogy Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Volume 5, Issue 3 | October 2018 | www.journaldialogue.org e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy is an open-access, peer-reviewed journal focused on the intersection of popular culture and pedagogy. While some open-access journals charge a publication fee for authors to submit, Dialogue is committed to creating and maintaining a scholarly journal that is accessible to all —meaning that there is no charge for either the author or the reader. The Journal is interested in contributions that offer theoretical, practical, pedagogical, and historical examinations of popular culture, including interdisciplinary discussions and those which examine the connections between American and international cultures. In addition to analyses provided by contributed articles, the Journal also encourages submissions for guest editions, interviews, and reviews of books, films, conferences, music, and technology. For more information and to submit manuscripts, please visit www.journaldialogue.org or email the editors, A. S. CohenMiller, Editor-in-Chief, or Kurt Depner, Managing Editor at [email protected]. All papers in Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share- Alike License. For details please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy EDITORIAL TEAM A. S. CohenMiller, PhD, Editor-in-Chief, Founding Editor Anna S. CohenMiller is a qualitative methodologist who examines pedagogical practices from preK – higher education, arts-based methods and popular culture representations. -

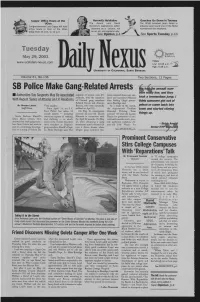

Tuesday P .La

Capps’ Office Hours at the Horowitz Hulabaloo Gauchos Go Down in Tourney UCen The Nexus runs David The UCSB baseball team failed to Congresswoman Lois Capps will hold Horowitz's pugnacious adver advance past round one of the NCAA office hours in front of the UCen tisement as a column, not tournament this weekend. today from 11 p.m. to 12 p.m. as an ad, and explains why. See Opinion p A See Sports Tuesday p .lA Tuesday Sunset May 29, 2001 8 :0 4 p.m. Tides — >. www.ucsbdailynexus.com Low: 1 0 :2 8 a.m. High: 5:38 p.m. Volume 81, No.136 Two Sections, 12 Pages SB Police Make Gang-Related Arrests , had the assault num- fts really low, and they ■ Authorities Say Suspects May Be Associated majority of victims were I.V. police arrested three more sus residents, with the exception pects and rearrested Miranda took a tremendous jump. I With Recent Series of Attacks on I.V. Residents of Oxnard gang members after finding illegal posses think someone got out of Edward Garcia and Antonio sions, Burridge said. B y M a r is a L a g o s Vista assaults. Becerra, who were reportedly As a result o f the search, prison or came back into Staff Writer Since April 14, the I.V. stabbed on April 22. the department’s Problem town and started stirring Foot Patrol has taken 12 On M ay 16, investigators Oriented Policing Team assault reports — including arrested 22-year-old Daniel arrested 18-year-old Jacabo things up. -

Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin

Traut 1 Katerina Traut Lehigh University Giving ‘Substance to Freedom and Democracy’: Black Woman Intellectual Vicki Garvin ABSTRACT: This paper explores labor organizer Vicki Garvin's life and ideas as an instantiation of Black feminism and as characterized by features central to contemporary Black feminist thought. Garvin's philosophy and practice of feminism come forth in her research and activism in worker’s rights, African American’s rights, and women’s rights. Garvin came of age in a post-WWII era of politics that was shaped by social movements toward liberation. As a demonstration of how to resist domination and oppression while remaining committed to the practice of democracy, Garvin's lifework deserves attention. INTRODUCTION According to Patricia Hill Collins, one distinguishing feature of Black feminist thought is that there is a dialectical relationship between oppression and activism, and there is a dialogical relationship between Black women's collective experiences of oppression and their group knowledge.1 Because of their unique position within the matrix of domination, defined as the social organization in which intersecting oppressions are developed, maintained, and maneuvered, African American women have a special knowledge about the interlocking nature of race, gender, and class oppression.2 Therefore, they must be a part of any effective effort to critique and overcome oppression. As Collins explains, this insight was known and practiced well before contemporary feminist thinkers such as herself conceptualized Black feminist thought as a particular field of scholarship. The research and activism of labor organizer Vicki Garvin demonstrates an understanding of the specific and important role that African American women (as one of many historically marginalized/oppressed groups) have to play within the Traut 2 institutional contexts that create and perpetuate their oppression. -

Liberal Bias in the Legal Academy: Overstated and Undervalued Michael Vitiello Pacific Cgem Orge School of Law

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2007 Liberal Bias in the Legal Academy: Overstated and Undervalued Michael Vitiello Pacific cGeM orge School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/facultyarticles Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Michael Vitiello, Liberal Bias in the Legal Academy: Overstated and Undervalued, 77 Miss. L.J. 507 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIBERAL BIAS IN THE LEGAL ACADEMY: OVERSTATED AND UNDERVALUED Michael Vitiello * I. INTRODUCTION By many accounts, universities are hotbeds of left-wing radicalism. 1 Often fueled by overreaching administrators, right- wing bloggers and radio talk show hosts rail against the sup- pression of free speech by the "politically correct" left wing. 2 Over the past twenty years, numerous and mostly conservative commentators have published books decrying radical professors and their efforts to force their own political vision on their stu- dents. 3 Most recently , former Communist turned hard-right • Distinguished Pr ofesso r and Scholar, Pacific McGeorge School of Law; B.A. Swarthmore, 1969; J.D . University of Penn sylvania, 1974. I want to extend special thanks to a wonderful group of research assistants who ran down obscure footnotes and converted oddball citation s into Bluebook form-thanks to Cameron Desmond, Oona Mallett, Alison Terry, Jennifer L.