"The Whole Nation Will Move": Grassroots Organizing in Harlem and the Advent of the Long, Hot Summers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHARLES L. ADKINS - Died Monday, April 23, 2018 at His Home in Bidwell, Ohio at the Age of 73

CHARLES L. ADKINS - Died Monday, April 23, 2018 at his home in Bidwell, Ohio at the age of 73. The cause of death is unknown. He was born on March 11, 1945 in Vinton, Ohio to the late William Raymond and Mary (née Poynter) Adkins. Charles married Mildred Adkins June 23, 1976 in Columbus, Ohio, who also preceded him in death October 20, 2007. Charles retired from General Motors following thirty years employment. He served in the United States Army and was a Veteran of the Vietnam Conflict. He was a member of Gallipolis VFW Post #4464; Gallipolis AMVETS Post #23; Gallipolis DAV Chapter #23; Vinton American Legion Post #161; life and a founding member of Springfield Volunteer Fire Department; life member of Vinton Volunteer Fire Department and a former chaplain and member Gallia County Sheriff’s Department. He attended several churches throughout Gallia County, Ohio. He was a member of Vietnam Veterans of America – Gallipolis Chapter #709. Those left behind to cherish his memory are two stepdaughters, Marcy Gregory, of Vinton, Ohio and Ramey (Bruce) Dray, of Gallipolis, Ohio; three stepsons, Sonny (Donna) Adkins, of Vinton, Ohio; Randy (Debbie) Adkins and Richard (Tonya) Adkins, both of Bidwell, Ohio; nine stepgrandchildren; eleven step-great- grandchildren, and; ten step-great-great-grandchildren; his brothers, Paul (Martha) Adkins, of Bidwell, Ohio and Fred Adkins, of Columbus, Ohio, and; his sister-in-law, Ellen Adkins, of Dandridge, Tennessee. In addition to his parents and wife, Charles is preceded in death by his sisters Donna Jean Higginbotham and Cloda Dray; his brothers, Raymond, Billy and Ronnie Adkins; his step-grandson, Shawn Gregory and his son-in-law, Rod Gregory. -

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

1 Building Bridges: the Challenge of Organized

BUILDING BRIDGES: THE CHALLENGE OF ORGANIZED LABOR IN COMMUNITIES OF COLOR Robin D. G. Kelley New York University [email protected] What roles can labor unions play in transforming our inner cities and promo ting policies that might improve the overall condition of working people of color? What happens when union organizers extend their reach beyond the workplace to the needs of working-class communities? What has been the historical role of unions in the larger struggles of people of color, particularly black workers? These are crucial questions in an age when production has become less pivotal to working-class life. Increasingly, we've witnessed the export of whole production processes as corporations moved outside the country in order to take advantage of cheaper labor, relatively lower taxes, and a deregulated, frequently antiunion environment. And the labor force itself has changed. The old images of the American workingclass as white men residing in sooty industrial suburbs and smokestack districts are increasingly rare. The new service-based economy has produced a working class increasingly concentrated in the healthcare professions, educational institutions, office building maintenance, food processing, food services and various retail establishments. 1 In the world of manufacturing, sweatshops are coming back, particularly in the garment industry and electronics assembling plants, and homework is growing. These unions are also more likely to be brown and female than they have been in the past. While white male membership dropped from 55.8% in 1986 to 49.7% in 1995, women now make up 37 percent of organized labor's membership -- a higher percentage than at any time in the U.S. -

Conrad Lynn to Speak at New York Forum

gtiiinimmiimiHi JOHNSON MOVES TO EXPLOIT HEALTH ISSUE THE Medicare As a Vote-Catching Gimmick By M arvel Scholl paign promises” file and dressed kept, so he can toss them around 1964 is a presidential election up in new language. as liberally as necessary, be in year so it is not surprising that Johnson and his Administration dignant, give facts and figures, President Johnson’s message to know exactly how little chance deplore and propose. MILITANT Congress on health and medical there is that any of the legislation He states that our medical sci Published in the Interests of the Working People care should sound like the he proposes has of getting through ence and all its related disciplines thoughtful considerations of a man the legislative maze of “checks are “unexcelled” but — each year Vol. 28 - No. 8 Monday, February 24, 1964 Price 10c and a party deeply concerned over and balances” (committees to thousands of infants die needless the general state of health of the committees, amendments, change, ly; half of the young men un entire nation. It is nothing of the debate and filibuster ad infini qualified for military services are kind. It is a deliberate campaign tum). Words are cheap, campaign rejected for medical reasons; one hoax, dragged out of an old “cam- promises are never meant to be third of all old age public as sistance is spent for medical care; Framed-Up 'Kidnap' Trial most contagious diseases have been conquered yet every year thousands suffer and die from ill nesses fo r w hich there are know n Opens in Monroe, N. -

Freedomways Magazine, Black Leftists, and Continuities in the Freedom Movement

Bearing the Seeds of Struggle: Freedomways Magazine, Black Leftists, and Continuities in the Freedom Movement Ian Rocksborough-Smith BA, Simon Fraser University, 2003 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History O Ian Rocksborough-Smith 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Ian Rocksborough-Smith Degree: Masters of Arts Title of Thesis: Bearing the Seeds of Struggle: Freedomways Magazine, Black Leftists, and Continuities in the Freedom Movement Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. John Stubbs ProfessorIDepartment of History Dr. Karen Ferguson Senior Supervisor Associate ProfessorIDepartment of History Dr. Mark Leier Supervisor Associate ProfessorIDepartment of History Dr. David Chariandy External ExaminerISimon Fraser University Assistant ProfessorIDepartment of English Date DefendedlApproved: Z.7; E0oS SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

KILLENS, JOHN OLIVER, 1916-1987. John Oliver Killens Papers, 1937-1987

KILLENS, JOHN OLIVER, 1916-1987. John Oliver Killens papers, 1937-1987 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Killens, John Oliver, 1916-1987. Title: John Oliver Killens papers, 1937-1987 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 957 Extent: 61.75 linear feet (127 boxes), 5 oversized papers boxes (OP), and 3 oversized bound volumes (OBV) Abstract: Papers of John Oliver Killens, African American novelist, essayist, screenwriter, and political activist, including correspondence, writings by Killens, writings by others, and printed material. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Series 5: Some student records are restricted until 2053. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Purchase, 2003 Citation [after identification of item(s)], John Oliver Killens papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Elizabeth Roke, Elizabeth Stice, and Margaret Greaves, June 2011 This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. Please refer to the Rose Library's harmful language statement for more information about why such language may appear and ongoing efforts to remediate racist, ableist, sexist, homophobic, euphemistic and other Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. John Oliver Killens papers, 1937-1987 Manuscript Collection No. 957 oppressive language. If you are concerned about language used in this finding aid, please contact us at [email protected]. -

Lf%J I Freedomways Reader

lf%J i Freedomways Reader Prophets in Country i edited by Esther Cooper Jackson K1NSSO ConStanCe PM> I Assistant Editor f^S^l ^ v^r II ^-^S A Member of the Perseus Books Group -\ ' Contents List of Photos xv Foreword, Julian Bond xvii Introduction, Esther Cooper Jackson xix Part I Origins of Freedomways J. H. O'Dell, 1 1 Behold the Land, No. 1, 1964, W.E.B. Du Bois 6 2 The Battleground Is Here, No. 1, 1971, Paul Robeson 12 3 Southern Youth's Proud Heritage, No. 1, 1964, Augusta Strong 16 4 Memoirs of a Birmingham Coal Miner, No. 1, 1964, Henry O. May field 21 5 "Not New Ground, but Rights Once Dearly Won," No. 1, 1962, Louis E. Burnham 26 6 Honoring Dr. Du Bois, No. 2, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. 31 7 Ode to Paul Robeson, No. 1, 1976, Pablo Neruda 40 CONTENTS Part 2, Reports from the Front Lines: Segregation in the South /. H. O'Dell, 47 8 The United States and the Negro, No. 1, 1961, W.E.B. Du Bois 50 9 A Freedom Rider Speaks His Mind, No. 2, 1961, Jimmy McDonald 59 10 What Price Prejudice? On the Economics of Discrimination, No. 3, 1962, Whitney M. Young Jr. 65 11 The Southern Youth Movement, No. 3, 1962, Julian Bond 69 12 Nonviolence: An Interpretation, No. 2, 1963, Julian Bond 71 13 Lorraine Hansberry at the Summit, No. 4, 1979, James Baldwin 77 14 "We're Moving!" No. 1, 1971, Paul Robeson 82 15 Birmingham Shall Be Free Some Day, No. -

Malcolm X at Opening Rally in Harlem

Young Socialists Win Acquittal in Indiana; “ Anti-Red” Law Declared Unconstitutional THE MILITANT Published in the Interests of the Working People V o l. 28 - No. 13 M onday, M a rch 30, 1964 P ric e 10c 3,000 Cheer Malcolm X At Opening Rally in Harlem By David Herman NEW YORK — An audience of rican brothers in the UN. We’ve over 3,000 responded enthusiast got Asian brothers in the UN. ically at the first of a series of We’ve got Latin American brothers Sunday night meetings organized in the UN . And then we’ve got by Malcolm X’s new black na 800 more million of them over in tionalist movement. The meeting C hina.” was held at the Rockland Palace Asked about the civil-rights bill, THE WINNERS. From left to right, Ralph Levitt, Tom Morgan and James Bingham, the Indiana in Harlem on March 22. Only Ne he said, “There’s nothing in that University students who won dismissal of their indictment under state “sedition” law. groes were admitted save for white civil-rights bill that’s going to help newspaper reporters. the Negroes in the North.” He By George Saunders law deals only with sedition against Hoadley’s indictments and Malcolm X attacked both the added that if the bill won’t help against a state government. This proposed evidence even before the Democratic and Republican parties Northern Negroes how can you A victory of great significance is a blow to the witch hunt, for M a rch 20 hearing. On M a rch 16 and called for a black nationalist expect it to help those in the for civil liberties and academic such state laws are still used — Daniel T. -

Diagnosis Nabj: a Preliminary Study of a Post-Civil Rights Organization

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository DIAGNOSIS NABJ: A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF A POST-CIVIL RIGHTS ORGANIZATION BY LETRELL DESHAN CRITTENDEN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor John Nerone, Chair Associate Professor Christopher Benson Associate Professor William Berry Associate Professor Clarence Lang, University of Kansas ABSTRACT This critical study interrogates the history of the National Association of Black Journalists, the nation’s oldest and largest advocacy organization for reporters of color. Founded in 1975, NABJ represents the quintessential post-Civil Rights organization, in that it was established following the end of the struggle for freedom rights. This piece argues that NABJ, like many other advocacy organizations, has succumbed to incorporation. Once a fierce critic of institutional racism inside and outside the newsroom, NABJ has slowly narrowed its advocacy focus to the issue of newsroom diversity. In doing so, NABJ, this piece argues, has rendered itself useless to the larger black public sphere, serving only the needs of middle-class African Americans seeking jobs within the mainstream press. Moreover, as the organization has aged, NABJ has taken an increasing amount of money from the very news organizations it seeks to critique. Additionally, this study introduces a specific method of inquiry known as diagnostic journalism. Inspired in part by the television show, House MD, diagnostic journalism emphasizes historiography, participant observation and autoethnography in lieu of interviewing. -

Black History, 1877-1954

THE BRITISH LIBRARY AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE: 1877-1954 A SELECTIVE GUIDE TO MATERIALS IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY BY JEAN KEMBLE THE ECCLES CENTRE FOR AMERICAN STUDIES AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE, 1877-1954 Contents Introduction Agriculture Art & Photography Civil Rights Crime and Punishment Demography Du Bois, W.E.B. Economics Education Entertainment – Film, Radio, Theatre Family Folklore Freemasonry Marcus Garvey General Great Depression/New Deal Great Migration Health & Medicine Historiography Ku Klux Klan Law Leadership Libraries Lynching & Violence Military NAACP National Urban League Philanthropy Politics Press Race Relations & ‘The Negro Question’ Religion Riots & Protests Sport Transport Tuskegee Institute Urban Life Booker T. Washington West Women Work & Unions World Wars States Alabama Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut District of Columbia Florida Georgia Illinois Indiana Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Nebraska Nevada New Jersey New York North Carolina Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania South Carolina Tennessee Texas Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming Bibliographies/Reference works Introduction Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, African American history, once the preserve of a few dedicated individuals, has experienced an expansion unprecedented in historical research. The effect of this on-going, scholarly ‘explosion’, in which both black and white historians are actively engaged, is both manifold and wide-reaching for in illuminating myriad aspects of African American life and culture from the colonial period to the very recent past it is simultaneously, and inevitably, enriching our understanding of the entire fabric of American social, economic, cultural and political history. Perhaps not surprisingly the depth and breadth of coverage received by particular topics and time-periods has so far been uneven. -

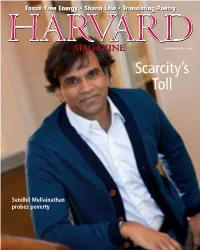

Scarcity's Toll

Fossil-Free Energy • Sharia Law • Translating Poetry May-June 2015 • $4.95 Scarcity’s Toll Sendhil Mullainathan probes poverty GO FURTHER THAN YOU EVER IMAGINED. INCREDIBLE PLACES. ENGAGING EXPERTS. UNFORGETTABLE TRIPS. Travel the world with National Geographic experts. From photography workshops to family trips, active adventures to classic train journeys, small-ship voyages to once-in-a-lifetime expeditions by private jet, our range of trips o ers something for everyone. Antarctica • Galápagos • Alaska • Italy • Japan • Cuba • Tanzania • Costa Rica • and many more! Call toll-free 1-888-966-8687 or visit nationalgeographicexpeditions.com/explore MAY-JUNE 2015 VOLUME 117, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 38 The Science of Scarcity | by Cara Feinberg Behavioral economist Sendhil Mullainathan reinterprets the causes and effects of poverty 44 Vita: Thomas Nuttall | by John Nelson Brief life of a pioneering naturalist: 1786-1859 46 Altering Course | by Jonathan Shaw p. 46 Mara Prentiss on the science of American energy consumption now— and in a newly sustainable era 52 Line by Line | by Spencer Lenfield David Ferry’s poems and “renderings” of literary classics are mutually reinforcing JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 17 Biomedical informatics and the advent of precision medicine, adept algorithmist, when tobacco stocks were tossed, studying sharia, climate-change currents and other Harvard headlines, the “new” in House renewal, a former governor as Commencement speaker, the Undergraduate’s electronic tethers, basketball’s rollercoaster season, hockey highlights, -

Influencer Marketing Class

WELCOME TO CAMPUS NEW YORK ! 1 UNIVERSIDAD ADOLFO IBANEZ & EFAP NEW YORK- NYIT 1855 Broadway, New York, NY 10023-USA PROGRAM DESCRIPTION § 15 Hours Lecture § 15 hours Conference,Professional meet up, company visits and workshop § 10 hours Cultural visits DATES § From July 19th to Friday 31st 2020 2 TENTATIVE SCHEDULE Week 1 Week 2 Morning Afternoon Morning Afternoon Pick –up & Sunday 19/7 Check in Transfer to Free Free hotel Welcome and Influencer Central Park Monday campus tour- Wall Street Marketing Visit Workshop class Conference & Influencer Tuesday Professional free Marketing Company visit meet up class Conference & Influencer Influencer Wednesday Professional Harlem Marketing Marketing meet up class class Conference & Influencer Company visit Professional Thursday free Marketing + meet up class Farewell diner Conference & Grand Check out Friday Professional Central 31/7 meet up Optional activity : 9/11 Saturday Museum with Memorial Tour - - 3 - Statue of Liberty CAMPUS ADDRESS: 1855 Broadway, New York, NY 10023-USA 4 Week 1: Conference & Professional Meet up/ Workshop Workshop: Narrative Storytelling -Exploration of how descriptive language advance a story in different art forms Conference & Professional Meet up The New Digital Marketing Trends – Benjamin Lord, Executive Director Global e-Commerce NARS at Shisheido Group (Expert in brand management, consumer technology and digital marketing at a global level) Conference & Professional Meet up Evolution of the Social Media Landscape and how to reinforce the social media engagement? Colin Dennison – Digital Communication Specialist at La Guardia Gateway Partners Conference & Professional Meet up From business intelligence to artificial intelligence: How the artificial intelligence will predict customer behavior – Xavier Degryse – President & Founder MX-Data (Leader in providing retail IT services to high profile customers in the luxury and fashion industries .