Punitive Articles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moves to Amend HF No. 752 As Follows: Delete Everything After the Enacting Clause and Insert

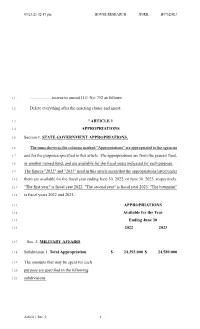

03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 752 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. STATE GOVERNMENT APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the columns marked "Appropriations" are appropriated to the agencies 1.7 and for the purposes specified in this article. The appropriations are from the general fund, 1.8 or another named fund, and are available for the fiscal years indicated for each purpose. 1.9 The figures "2022" and "2023" used in this article mean that the appropriations listed under 1.10 them are available for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2022, or June 30, 2023, respectively. 1.11 "The first year" is fiscal year 2022. "The second year" is fiscal year 2023. "The biennium" 1.12 is fiscal years 2022 and 2023. 1.13 APPROPRIATIONS 1.14 Available for the Year 1.15 Ending June 30 1.16 2022 2023 1.17 Sec. 2. MILITARY AFFAIRS 1.18 Subdivision 1. Total Appropriation $ 24,393,000 $ 24,589,000 1.19 The amounts that may be spent for each 1.20 purpose are specified in the following 1.21 subdivisions. Article 1 Sec. 2. 1 03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 2.1 Subd. 2. Maintenance of Training Facilities 9,772,000 9,772,000 2.2 Subd. 3. General Support 3,507,000 3,633,000 2.3 Subd. 4. Enlistment Incentives 11,114,000 11,114,000 2.4 The appropriations in this subdivision are 2.5 available until June 30, 2025, except that any 2.6 unspent amounts allocated to a program 2.7 otherwise supported by this appropriation are 2.8 canceled to the general fund upon receipt of 2.9 federal funds in the same amount to support 2.10 administration of that program. 2.11 If the amount for fiscal year 2022 is 2.12 insufficient, the amount for 2023 is available 2.13 in fiscal year 2022. -

Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?

Nebraska Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Article 8 1955 Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness? James W. Hewitt University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation James W. Hewitt, Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?, 34 Neb. L. Rev. 518 (1954) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol34/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 518 NEBRASKA LAW REVIEW CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-UNIFORM CODE OF MILITARY JUSTICE-GENERAL ARTICLE VOID FOR VAGUENESS.? Much has been said or written about the rights of servicemen under the new Uniform Code of Military Justice,1 which is the source of American written military law. Some of the major criticisms of military law have been that it is too harsh, too vague, and too careless of the right to due process of law. A large por tion of this criticism has been leveled at Article 134,2 the general, catch-all article of the Code. Article 134 provides: 3~ Alabama. Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, l\Iaine, l\Iaryland, l\Iasschusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Vermont. South Carolina has the privilege by case decision. See note 4 supra. 1 64 Stat. 107 <1950l, 50 U.S.C. §§ 551-736 (1952). -

Gentlemen Under Fire: the U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 1 June 2008 Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming Elizabeth L. Hillman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Elizabeth L. Hillman, Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming, 26(1) LAW & INEQ. 1 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol26/iss1/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Gentlemen Under Fire: The U.S. Military and "Conduct Unbecoming" Elizabeth L. Hillmant Introduction ..................................................................................1 I. Creating an Officer Class ..................................................10 A. "A Scandalous and Infamous" Manner ...................... 11 B. The "Military Art" and American Gentility .............. 12 C. Continental Army Prosecutions .................................15 II. Building a Profession .........................................................17 A. Colonel Winthrop's Definition ...................................18 B. "A Stable Fraternity" ................................................. 19 C. Old Army Prosecutions ..............................................25 III. Defending a Standing Army ..............................................27 A. "As a Court-Martial May Direct". ............................. 27 B. Democratization and its Discontents ........................ 33 C. Cold War Prosecutions ..............................................36 -

Volume 4 Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2015

TM VOLUME 4 ISSUE 1 FALL/WINTER 2015 National Security Law Journal George Mason University School of Law 3301 Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22201 www.nslj.org © 2015 National Security Law Journal. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Publication Data (Serial) National Security Law Journal. Arlington, Va. : National Security Law Journal, 2013- K14 .N18 ISSN: 2373-8464 Variant title: NSLJ National security—Law and legislation—Periodicals LC control no. 2014202997 (http://lccn.loc.gov/2014202997) Past issues available in print at the Law Library Reading Room of the Library of Congress (Madison, LM201). VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 (FALL/WINTER 2015) ISBN-13: 978-1523203987 ISBN-10: 1523203986 ARTICLES PLANNING FOR CHANGE: BUILDING A FRAMEWORK TO PREDICT FUTURE CHANGES TO THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT Patrick Walsh QUANTUM LAWMAKING: HOW NATIONAL SECURITY LAW HAPPENS WHEN WE’RE NOT LOOKING Jesse Medlong COMMENTS TERROR IN MEXICO: WHY DESIGNATING MEXICAN CARTELS AS TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS EASES PROSECUTION OF DRUG TRAFFICKERS UNDER THE NARCOTERRORISM STATUTE Stephen R. Jackson CYBERSPACE: THE 21ST-CENTURY BATTLEFIELD EXPOSING SOLDIERS, SAILORS, AIRMEN, AND MARINES TO POTENTIAL CIVIL LIABILITIES Molly Picard VOLUME 4 FALL/WINTER 2015 ISSUE 1 PUBLISHED BY GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW Cite as 4 NAT’L SEC. L.J. ___ (2015). The National Security Law Journal (“NSLJ”) is a student-edited legal periodical published twice annually at George Mason University School of Law in Arlington, Virginia. We print timely, insightful scholarship on pressing matters that further the dynamic field of national security law, including topics relating to foreign affairs, homeland security, intelligence, and national defense. Visit our website at www.nslj.org to read our issues online, purchase the print edition, submit an article, learn about our upcoming events, or sign up for our e-mail newsletter. -

Pub. L. 108–136, Div. A, Title V, §509(A)

§ 777a TITLE 10—ARMED FORCES Page 384 Oct. 5, 1999, 113 Stat. 590; Pub. L. 108–136, div. A, for a period of up to 14 days before assuming the title V, § 509(a), Nov. 24, 2003, 117 Stat. 1458; Pub. duties of a position for which the higher grade is L. 108–375, div. A, title V, § 503, Oct. 28, 2004, 118 authorized. An officer who is so authorized to Stat. 1875; Pub. L. 109–163, div. A, title V, wear the insignia of a higher grade is said to be §§ 503(c), 504, Jan. 6, 2006, 119 Stat. 3226; Pub. L. ‘‘frocked’’ to that grade. 111–383, div. A, title V, § 505(b), Jan. 7, 2011, 124 (b) RESTRICTIONS.—An officer may not be au- Stat. 4210.) thorized to wear the insignia for a grade as de- scribed in subsection (a) unless— AMENDMENTS (1) the Senate has given its advice and con- 2011—Subsec. (b)(3)(B). Pub. L. 111–383 struck out sent to the appointment of the officer to that ‘‘and a period of 30 days has elapsed after the date of grade; the notification’’ after ‘‘grade’’. 2006—Subsec. (a). Pub. L. 109–163, § 503(c), inserted ‘‘in (2) the officer has received orders to serve in a grade below the grade of major general or, in the case a position outside the military department of of the Navy, rear admiral,’’ after ‘‘An officer’’ in first that officer for which that grade is authorized; sentence. (3) the Secretary of Defense (or a civilian of- Subsec. (d)(1). -

Military Courts and Article III

Military Courts and Article III STEPHEN I. VLADECK* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................... 934 I. MILITARY JUSTICE AND ARTICLE III: ORIGINS AND CASE LAW ...... 939 A. A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO U.S. MILITARY COURTS ........... 941 1. Courts-Martial ............................... 941 2. Military Commissions ......................... 945 B. THE NORMATIVE JUSTIFICATIONS FOR MILITARY JUSTICE ....... 948 C. THE SUPREME COURT’S CONSTITUTIONAL DEFENSE OF COURTS-MARTIAL ................................. 951 D. THE SUPREME COURT’S CONSTITUTIONAL DEFENSE OF MILITARY COMMISSIONS .................................... 957 II. RECENT EXPANSIONS TO MILITARY JURISDICTION ............... 961 A. SOLORIO AND THE SERVICE-CONNECTION TEST .............. 962 B. ALI AND CHIEF JUDGE BAKER’S BLURRING OF SOLORIO’S BRIGHT LINE .......................................... 963 C. THE MCA AND THE “U.S. COMMON LAW OF WAR” ............ 965 D. ARTICLE III AND THE CIVILIANIZATION OF MILITARY JURISDICTION .................................... 966 E. RECONCILING THE MILITARY EXCEPTION WITH CIVILIANIZATION .................................. 968 * Professor of Law, American University Washington College of Law. © 2015, Stephen I. Vladeck. For helpful discussions and feedback, I owe deep thanks to Zack Clopton, Jen Daskal, Mike Dorf, Gene Fidell, Barry Friedman, Amanda Frost, Dave Glazier, David Golove, Tara Leigh Grove, Ed Hartnett, Harold Koh, Marty Lederman, Peter Margulies, Jim Pfander, Zach Price, Judith Resnik, Gabor Rona, Carlos Va´zquez, Adam Zimmerman, students in my Fall 2013 seminar on military courts, participants in the Hauser Globalization Colloquium at NYU and Northwestern’s Public Law Colloquium, and colleagues in faculty workshops at Cardozo, Cornell, DePaul, FIU, Hastings, Loyola, Rutgers-Camden, and Stanford. Thanks also to Cynthia Anderson, Gabe Auteri, Gal Bruck, Caitlin Marchand, and Pasha Sternberg for research assistance; and to Dean Claudio Grossman for his generous and unstinting support of this project. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. __________ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States LAWRENCE G. HUTCHINS III, SERGEANT, UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI S. BABU KAZA CHRIS G. OPRISON LtCol, USMCR DLA Piper LLP (US) THOMAS R. FRICTON 500 8th St, NW Captain, USMC Washington DC Counsel of Record Civilian Counsel for U.S. Navy-Marine Corps Petitioner Appellate Defense Division 202-664-6543 1254 Charles Morris St, SE Washington Navy Yard, D.C. 20374 202-685-7291 [email protected] i QUESTION PRESENTED In Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970), this Court held that the collateral estoppel aspect of the Double Jeopardy Clause bars a prosecution that depends on a fact necessarily decided in the defendant’s favor by an earlier acquittal. Here, the Petitioner, Sergeant Hutchins, successfully fought war crime charges at his first trial which alleged that he had conspired with his subordinate Marines to commit a killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim. The members panel (jury) specifically found Sergeant Hutchins not guilty of that aspect of the conspiracy charge, and of the corresponding overt acts and substantive offenses. The panel instead found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the lesser-included offense of conspiring to commit an unlawful killing of a named suspected insurgent leader, and found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the substantive crimes in furtherance of that specific conspiracy. After those convictions were later reversed, Sergeant Hutchins was taken to a second trial in 2015 where the Government once again alleged that the charged conspiracy agreement was for the killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim, and presented evidence of the overt acts and criminal offenses for which Sergeant Hutchins had previously been acquitted. -

Military Law Review

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY PAMPHLET 27-1 00-21 MILITARY LAW REVIEW Articles KIDNAPPISG AS A 1IIILITARY OFFENSE Major hfelburn N. washburn RELA TI OX S HIP BETTYEE?; A4PPOISTED AND INDI T’IDUAL DEFENSE COUNSEL Lievtenant Commander James D. Nrilder COI~1KTATIONOF SIILITARY SENTENCES Milton G. Gershenson LEGAL ASPECTS OF MILITARY OPERATIONS IN COUNTERINSURGENCY Major Joseph B. Kelly SWISS MILITARY JUSTICE Rene‘ Depierre Comments 1NTERROC;ATION UNDER THE 1949 PRISOKERS OF TT-AR CON-EKTIO?; ONE HLSDREClTH ANNIS’ERSARY OF THE LIEBER CODE HEA,DQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY JULY 1963 PREFACE The Milita.ry Law Review is designed to provide a medium for those interested in the field of military law to share the product of their experience and research with their fellow lawyers. Articles should be of direct concern and import in this area of scholarship, and preference will be given to those articles having lasting value as reference material for the military lawyer. The Jli7itm~Law Review does not purport tg promulgate Depart- ment of the Army policy or to be in any sense directory. The opinions reflected in each article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Judge Advocate General or the Department of the Army. Articles, comments, and notes should be submitted in duplicate, triple spnced, to the Editor, MiZitary Law Review. The Judge Advo- cate General’s School, US. Army, Charlottewille, Virginia. Foot- notes should be triple spaced, set out on pages separate from the text and follow the manner of citation in the Harvard Blue Rook. -

Kansas Army National Guard Leader's Handbook

Kansas Army National Guard Leader’s Handbook Office of the Inspector General Kansas National Guard 9 October 2012 PREFACE “The day Soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help them or concluded that you do not care. Either case is a failure of leadership.” -Colin Powell This handbook can be used as an effective and informative tool to assist leaders concerning day- to-day Soldier issues. When using this handbook, keep in mind that it does not supersede or replace any Army or State regulation. Leaders should know that this guide is not designed to be an “off-the-shelf,” one- size-fits-all,” cookbook. Rather, it is a starting point and all of these potential actions encompassed in the guide are fact driven. Each situation is unique and specific facts will determine the right process or procedure to follow in that situation. The most important factor in resolving any issue is the Leader’s judgment. No matter what the contemplated action is, the Leader must eye-ball a situation and decide what is the right thing to do, then bring all of his/her maturity, experience, and background into play. As of the publication date, the information in this handbook is current. However, regulations are subject to change. Before taking any final action, Leaders must refer to the appropriate regulation. The Inspector General Staff 2 Table of Contents SECTION I Leadership References 6 Purpose 6 Scope 6 What is a leader? 6 What is an Army leader? 6 What makes an Army leader? 6 Character & Integrity above all 6 Things Leaders Must do 7 Things Leaders must NOT do 7 Things that get Leaders into Trouble 8 Leadership vs. -

Criminal Law Deskbook, Volume II, Crimes and Defenses

CRIMINAL LAW DESKBOOK Volume II Crimes and Defenses The Judge Advocate General’s School, US Army Charlottesville, Virginia Summer 2010 FOREWORD The Criminal Law Department at The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School, US Army, (TJAGLCS) produces this deskbook as a resource for Judge Advocates, both in training and in the field, and for use by other military justice practitioners. This deskbook covers many aspects of military justice, including procedure (Volume I) and substantive criminal law (Volume II). Military justice practitioners and military justice managers are free to reproduce as many paper copies as needed. The deskbook is neither an all-encompassing academic treatise nor a definitive digest of all military criminal caselaw. Practitioners should always consult relevant primary sources, including the decisions in cases referenced herein. Nevertheless, to the extent possible, it is an accurate, current, and comprehensive resource. Readers noting any discrepancies or having suggestions for this deskbook's improvement are encouraged to contact the TJAGLCS Criminal Law Department. Current departmental contact information is provided at the back of this deskbook. //Original Signed// DANIEL G. BROOKHART LTC, JA Chair, Criminal Law Department TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: SCOPE OF CRIMINAL LIABILITY................................................................ 1 I. PRINCIPALS. UCMJ ART. 77....................................................................... 1 II. ACCESSORY AFTER THE FACT. UCMJ ART. 78. ................................. -

Judicial Review of the Manual for Courts-Martial

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by George Washington University Law School GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 1999 Judicial Review of the Manual for Courts-Martial Gregory E. Maggs George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gregory E. Maggs, Judicial Review of the Manual for Courts-Martial, 160 Mil. L. Rev. 96 (1999). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Citation: 160 Mil. L. Rev. 96 (1999) JUDICIAL REVIEW OF THE MANUAL FOR COURTS-MARTIAL Captain Gregory E. Maggs1 Opinions and conclusions in articles published in the Military Law Review are solely those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Judge Advocate General, the Department of the Army, or any other government agency. I. Introduction The Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) establishes the basic structure of the military justice system.2 It specifies the requirements for convening courts-martial,3 defines the jurisdiction of courts-martial,4 and identifies the offenses that courts-martial may punish.5 Congress, however, did not intend the UCMJ to stand-alone. On the contrary, it specifically directed the President to promulgate procedural, evidentiary, and other rules to govern the military justice system.6 The President has complied with this directive by issuing a series of executive orders, which make up the Manual for Courts-Martial (Manual).7 1 Judge Advocate General’s Corps, United States Army Reserve. -

Conceptualizing the Tensions Evoked by Gender Integration in the Military

Special Issue: Women in the Military Armed Forces & Society 2017, Vol. 43(2) 202-220 ª The Author(s) 2016 Conceptualizing the Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0095327X16670692 Tensions Evoked by journals.sagepub.com/home/afs Gender Integration in the Military: The South African Case Lindy Heinecken1 Editor’s Note: This is the first of nine articles of the Armed Forces & Society Special Issue on Women in the Military appearing in Volume 43, Issue 2. Abstract The South African military has adopted an assertive affirmative action campaign to ensure that women are represented across all ranks and branches. This has brought about new tensions in terms of gender integration, related to issues of equal opportunities and meritocracy as well as the accommodation of gender difference and alternative values. The argument is made that the management of gender integration from a gender-neutral perspective cannot bring about gender equality, as it obliges women to conform to and assimilate masculine traits. This affects women’s ability to function as equals, especially where feminine traits are not valued, where militarized masculinities are privileged and where women are othered in ways that contribute to their subordination. Under such conditions, it is exceedingly difficult for women to bring about a more androgynous military culture espoused by gender mainstreaming initiatives and necessary for the type of missions military personnel are engaged in today. Keywords gender integration, equal opportunities, meritocracy, masculinity, femininity, military culture, gender mainstreaming 1 University of Steilenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa Corresponding Author: Lindy Heinecken, University of Steilenbosch, Private Bag X1, Matieland, Stellenbosch 7602, South Africa.