Judicial Review of the Manual for Courts-Martial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moves to Amend HF No. 752 As Follows: Delete Everything After the Enacting Clause and Insert

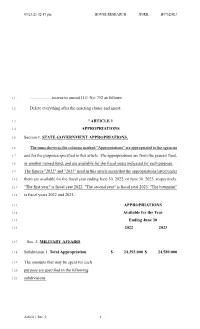

03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 752 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. STATE GOVERNMENT APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the columns marked "Appropriations" are appropriated to the agencies 1.7 and for the purposes specified in this article. The appropriations are from the general fund, 1.8 or another named fund, and are available for the fiscal years indicated for each purpose. 1.9 The figures "2022" and "2023" used in this article mean that the appropriations listed under 1.10 them are available for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2022, or June 30, 2023, respectively. 1.11 "The first year" is fiscal year 2022. "The second year" is fiscal year 2023. "The biennium" 1.12 is fiscal years 2022 and 2023. 1.13 APPROPRIATIONS 1.14 Available for the Year 1.15 Ending June 30 1.16 2022 2023 1.17 Sec. 2. MILITARY AFFAIRS 1.18 Subdivision 1. Total Appropriation $ 24,393,000 $ 24,589,000 1.19 The amounts that may be spent for each 1.20 purpose are specified in the following 1.21 subdivisions. Article 1 Sec. 2. 1 03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 2.1 Subd. 2. Maintenance of Training Facilities 9,772,000 9,772,000 2.2 Subd. 3. General Support 3,507,000 3,633,000 2.3 Subd. 4. Enlistment Incentives 11,114,000 11,114,000 2.4 The appropriations in this subdivision are 2.5 available until June 30, 2025, except that any 2.6 unspent amounts allocated to a program 2.7 otherwise supported by this appropriation are 2.8 canceled to the general fund upon receipt of 2.9 federal funds in the same amount to support 2.10 administration of that program. 2.11 If the amount for fiscal year 2022 is 2.12 insufficient, the amount for 2023 is available 2.13 in fiscal year 2022. -

Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?

Nebraska Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Article 8 1955 Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness? James W. Hewitt University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation James W. Hewitt, Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?, 34 Neb. L. Rev. 518 (1954) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol34/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 518 NEBRASKA LAW REVIEW CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-UNIFORM CODE OF MILITARY JUSTICE-GENERAL ARTICLE VOID FOR VAGUENESS.? Much has been said or written about the rights of servicemen under the new Uniform Code of Military Justice,1 which is the source of American written military law. Some of the major criticisms of military law have been that it is too harsh, too vague, and too careless of the right to due process of law. A large por tion of this criticism has been leveled at Article 134,2 the general, catch-all article of the Code. Article 134 provides: 3~ Alabama. Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, l\Iaine, l\Iaryland, l\Iasschusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Vermont. South Carolina has the privilege by case decision. See note 4 supra. 1 64 Stat. 107 <1950l, 50 U.S.C. §§ 551-736 (1952). -

Gentlemen Under Fire: the U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 1 June 2008 Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming Elizabeth L. Hillman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Elizabeth L. Hillman, Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming, 26(1) LAW & INEQ. 1 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol26/iss1/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Gentlemen Under Fire: The U.S. Military and "Conduct Unbecoming" Elizabeth L. Hillmant Introduction ..................................................................................1 I. Creating an Officer Class ..................................................10 A. "A Scandalous and Infamous" Manner ...................... 11 B. The "Military Art" and American Gentility .............. 12 C. Continental Army Prosecutions .................................15 II. Building a Profession .........................................................17 A. Colonel Winthrop's Definition ...................................18 B. "A Stable Fraternity" ................................................. 19 C. Old Army Prosecutions ..............................................25 III. Defending a Standing Army ..............................................27 A. "As a Court-Martial May Direct". ............................. 27 B. Democratization and its Discontents ........................ 33 C. Cold War Prosecutions ..............................................36 -

Volume 4 Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2015

TM VOLUME 4 ISSUE 1 FALL/WINTER 2015 National Security Law Journal George Mason University School of Law 3301 Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22201 www.nslj.org © 2015 National Security Law Journal. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Publication Data (Serial) National Security Law Journal. Arlington, Va. : National Security Law Journal, 2013- K14 .N18 ISSN: 2373-8464 Variant title: NSLJ National security—Law and legislation—Periodicals LC control no. 2014202997 (http://lccn.loc.gov/2014202997) Past issues available in print at the Law Library Reading Room of the Library of Congress (Madison, LM201). VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 (FALL/WINTER 2015) ISBN-13: 978-1523203987 ISBN-10: 1523203986 ARTICLES PLANNING FOR CHANGE: BUILDING A FRAMEWORK TO PREDICT FUTURE CHANGES TO THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT Patrick Walsh QUANTUM LAWMAKING: HOW NATIONAL SECURITY LAW HAPPENS WHEN WE’RE NOT LOOKING Jesse Medlong COMMENTS TERROR IN MEXICO: WHY DESIGNATING MEXICAN CARTELS AS TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS EASES PROSECUTION OF DRUG TRAFFICKERS UNDER THE NARCOTERRORISM STATUTE Stephen R. Jackson CYBERSPACE: THE 21ST-CENTURY BATTLEFIELD EXPOSING SOLDIERS, SAILORS, AIRMEN, AND MARINES TO POTENTIAL CIVIL LIABILITIES Molly Picard VOLUME 4 FALL/WINTER 2015 ISSUE 1 PUBLISHED BY GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW Cite as 4 NAT’L SEC. L.J. ___ (2015). The National Security Law Journal (“NSLJ”) is a student-edited legal periodical published twice annually at George Mason University School of Law in Arlington, Virginia. We print timely, insightful scholarship on pressing matters that further the dynamic field of national security law, including topics relating to foreign affairs, homeland security, intelligence, and national defense. Visit our website at www.nslj.org to read our issues online, purchase the print edition, submit an article, learn about our upcoming events, or sign up for our e-mail newsletter. -

Pub. L. 108–136, Div. A, Title V, §509(A)

§ 777a TITLE 10—ARMED FORCES Page 384 Oct. 5, 1999, 113 Stat. 590; Pub. L. 108–136, div. A, for a period of up to 14 days before assuming the title V, § 509(a), Nov. 24, 2003, 117 Stat. 1458; Pub. duties of a position for which the higher grade is L. 108–375, div. A, title V, § 503, Oct. 28, 2004, 118 authorized. An officer who is so authorized to Stat. 1875; Pub. L. 109–163, div. A, title V, wear the insignia of a higher grade is said to be §§ 503(c), 504, Jan. 6, 2006, 119 Stat. 3226; Pub. L. ‘‘frocked’’ to that grade. 111–383, div. A, title V, § 505(b), Jan. 7, 2011, 124 (b) RESTRICTIONS.—An officer may not be au- Stat. 4210.) thorized to wear the insignia for a grade as de- scribed in subsection (a) unless— AMENDMENTS (1) the Senate has given its advice and con- 2011—Subsec. (b)(3)(B). Pub. L. 111–383 struck out sent to the appointment of the officer to that ‘‘and a period of 30 days has elapsed after the date of grade; the notification’’ after ‘‘grade’’. 2006—Subsec. (a). Pub. L. 109–163, § 503(c), inserted ‘‘in (2) the officer has received orders to serve in a grade below the grade of major general or, in the case a position outside the military department of of the Navy, rear admiral,’’ after ‘‘An officer’’ in first that officer for which that grade is authorized; sentence. (3) the Secretary of Defense (or a civilian of- Subsec. (d)(1). -

2000 Foot Problems at Harris Seminar, Nov

CALIFORNIA THOROUGHBRED Adios Bill Silic—Mar. 79 sold at Keeneland, Oct—13 Adkins, Kirk—Nov. 20p; demonstrated new techniques for Anson, Ron & Susie—owners of Peach Flat, Jul. 39 2000 foot problems at Harris seminar, Nov. 21 Answer Do S.—won by Full Moon Madness, Jul. 40 JANUARY TO DECEMBER Admirably—Feb. 102p Answer Do—Jul. 20; 3rd place finisher in 1990 Cal Cup Admise (Fr)—Sep. 18 Sprint, Oct. 24; won 1992 Cal Cup Sprint, Oct. 24 Advance Deposit Wagering—May. 1 Anthony, John Ed—Jul. 9 ABBREVIATIONS Affectionately—Apr. 19 Antonsen, Per—co-owner stakes winner Rebuild Trust, Jun. AHC—American Horse Council Affirmed H.—won by Tiznow, Aug. 26 30; trainer at Harris Farms, Dec. 22; cmt. on early training ARCI—Association of Racing Commissioners International Affirmed—Jan. 19; Laffit Pincay Jr.’s favorite horse & winner of Tiznow, Dec. 22 BC—Breeders’ Cup of ’79 Hollywood Gold Cup, Jan. 12; Jan. 5p; Aug. 17 Apollo—sire of Harvest Girl, Nov. 58 CHRB—California Horse Racing Board African Horse Sickness—Jan. 118 Applebite Farms—stand stallion Distinctive Cat, Sep. 23; cmt—comment Africander—Jan. 34 Oct. 58; Dec. 12 CTBA—California Thoroughbred Breeders Association Aga Khan—bred Khaled in England, Apr. 19 Apreciada—Nov. 28; Nov. 36 CTBF—California Thoroughbred Breeders Foundation Agitate—influential broodmare sire for California, Nov. 14 Aptitude—Jul. 13 CTT—California Thorooughbred Trainers Agnew, Dan—Apr. 9 Arabian Light—1999 Del Mar sale graduate, Jul. 18p; Jul. 20; edit—editorial Ahearn, James—co-author Efficacy of Breeders Award with won Graduation S., Sep. 31; Sep. -

Military Courts and Article III

Military Courts and Article III STEPHEN I. VLADECK* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................... 934 I. MILITARY JUSTICE AND ARTICLE III: ORIGINS AND CASE LAW ...... 939 A. A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO U.S. MILITARY COURTS ........... 941 1. Courts-Martial ............................... 941 2. Military Commissions ......................... 945 B. THE NORMATIVE JUSTIFICATIONS FOR MILITARY JUSTICE ....... 948 C. THE SUPREME COURT’S CONSTITUTIONAL DEFENSE OF COURTS-MARTIAL ................................. 951 D. THE SUPREME COURT’S CONSTITUTIONAL DEFENSE OF MILITARY COMMISSIONS .................................... 957 II. RECENT EXPANSIONS TO MILITARY JURISDICTION ............... 961 A. SOLORIO AND THE SERVICE-CONNECTION TEST .............. 962 B. ALI AND CHIEF JUDGE BAKER’S BLURRING OF SOLORIO’S BRIGHT LINE .......................................... 963 C. THE MCA AND THE “U.S. COMMON LAW OF WAR” ............ 965 D. ARTICLE III AND THE CIVILIANIZATION OF MILITARY JURISDICTION .................................... 966 E. RECONCILING THE MILITARY EXCEPTION WITH CIVILIANIZATION .................................. 968 * Professor of Law, American University Washington College of Law. © 2015, Stephen I. Vladeck. For helpful discussions and feedback, I owe deep thanks to Zack Clopton, Jen Daskal, Mike Dorf, Gene Fidell, Barry Friedman, Amanda Frost, Dave Glazier, David Golove, Tara Leigh Grove, Ed Hartnett, Harold Koh, Marty Lederman, Peter Margulies, Jim Pfander, Zach Price, Judith Resnik, Gabor Rona, Carlos Va´zquez, Adam Zimmerman, students in my Fall 2013 seminar on military courts, participants in the Hauser Globalization Colloquium at NYU and Northwestern’s Public Law Colloquium, and colleagues in faculty workshops at Cardozo, Cornell, DePaul, FIU, Hastings, Loyola, Rutgers-Camden, and Stanford. Thanks also to Cynthia Anderson, Gabe Auteri, Gal Bruck, Caitlin Marchand, and Pasha Sternberg for research assistance; and to Dean Claudio Grossman for his generous and unstinting support of this project. -

EDITED PEDIGREE for 2011 out of KELSO MAGIC (USA)

EDITED PEDIGREE for 2011 out of KELSO MAGIC (USA) Pivotal (GB) Polar Falcon (USA) Sire: (Chesnut 1993) Fearless Revival CAPTAIN RIO (GB) (Chesnut 1999) Beloved Visitor (USA) Miswaki (USA) (Bay 1988) Abeesh (USA) (Chesnut colt 2011) Distant View (USA) Mr Prospector (USA) Dam: (Chesnut 1991) Seven Springs (USA) KELSO MAGIC (USA) (Chesnut 1997) Bowl of Honey (USA) Lyphard (USA) (Bay 1986) Golden Bowl (USA) 4Sx3D Mr Prospector (USA), 5Sx5Sx4D Northern Dancer, 5Sx4D Raise A Native, 5Sx4D Gold Digger (USA), 5Dx3D Lyphard (USA), 5Sx5D Court Martial 1st Dam KELSO MAGIC (USA), won 2 races at 2 years and £11,390 and placed 4 times; dam of 3 winners: FONGTASTIC (GB) (2002 g. by Dr Fong (USA)), won 1 race at 2 years and £4,269 and placed once; also won 3 races in U.S.A. from 4 to 6 years and £53,219 and placed 12 times. JOPAU (GB) (2004 c. by Dr Fong (USA)), won 2 races at 2 years and £17,951; also won 2 races in Hong Kong at 4 and 6 years and £103,769 and placed 7 times. BEN'S DREAM (IRE) (2006 g. by Kyllachy (GB)), won 1 race at 3 years and £10,056 and placed 6 times. Ches Jicaro (IRE) (2008 g. by Majestic Missile (IRE)). Captaen (IRE) (2010 c. by Captain Marvelous (IRE)). 2nd Dam BOWL OF HONEY (USA), unraced; dam of 3 winners: Proceeded (USA) (c. by Affirmed (USA)), won 3 races in U.S.A. at 4 years and £76,922, placed third in Bowling Green Handicap, Belmont Park, Gr.2 and Red Smith Handicap, Aqueduct, Gr.2. -

From Lisheen Stud Lord Gayle Sir Gaylord Sticky Case Lord Americo Hynictus Val De Loir Hypavia Roselier Misti IV Peace Rose QUAR

From Lisheen Stud 1 1 Sir Gaylord Lord Gayle Sticky Case Lord Americo Val de Loir QUARRYFIELD LASS Hynictus (IRE) Hypavia (1998) Misti IV Right Then Roselier Bay Mare Peace Rose Rosie (IRE) No Argument (1991) Right Then Esplanade 1st dam RIGHT THEN ROSIE (IRE): placed in a point-to-point; dam of 6 foals; 3 runners; 3 winners: Quarryfield Lass (IRE) (f. by Lord Americo): see below. Graduand (IRE) (g. by Executive Perk): winner of a N.H. Flat Race and placed twice; also placed over hurdles. Steve Capall (IRE) (g. by Dushyantor (USA)): winner of a N.H. Flat Race at 5, 2008 and placed twice. 2nd dam RIGHT THEN: ran 3 times over hurdles; dam of 8 foals; 5 runners; a winner: Midsummer Glen (IRE): winner over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Big Polly: unraced; dam of winners inc.: Stagalier (IRE): 4 wins viz. 3 wins over hurdles and placed 3 times inc. 3rd Brown Lad H. Hurdle, L. and winner over fences. Wyatt (IRE): 2 wins viz. placed; also winner over hurdles and placed 5 times and winner over fences, 2nd Naas Novice Steeplechase, Gr.3. 3rd dam ESPLANADE (by Escart III): winner at 5 and placed; also placed twice over jumps; dam of 5 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners inc.: Ballymac Lad: 4 wins viz. placed at 5; also winner of a N.H. Flat Race and placed 4 times; also 2 wins over hurdles, 2nd Celbridge Extended H. Hurdle, L. and Coral Golden EBF Stayers Ext H'cp Hurdle, L. and winner over fences. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Newsletter MONDAY, 1 MAY 2017

Newsletter MONDAY, 1 MAY 2017 www.turftalk.co.za The David Allan Column Newer names and different equine faces The grey Megaspiel (by Singspiel), shows off her filly by War Command. IN past columns or round a table, reference has aments presents a challenge. been made to more overseas pedigrees filtering into the gene pool in South Africa. Broodmare Having myself bought last year (for an amazed purchases, imported stallions and perhaps liberated client) a close relative of SAKHEE by lovely international trade are all factors. broodmare sire MEDICEAN by MACHIAVEL- LIAN for R175,000, I thought that we could chat We have observed that our SA trainers carry the here about some names within our own team of burden of having to - in addition to training the investor mares in the northern hemisphere. horses - “do the buying” i.e. researching multiple Your appetite for FRANKEL references will be catalogues and often travelling away in a manner sated – he does crop up below – but then so do not mirrored in other places. A proliferation of new KODI BEAR and HOT STREAK. (to page 2) names and associated conformations and tempera- 1 DAVID ALLAN For hands-off investors, we provide a complete range of selection, mating and management ser- vices with constant communication, visit arrange- ments, transport when necessary and book-keeping. Our people include local novices and experienced overseas people. If with SA connections, the rationale is to generate sterling and euro to reinvest or buy something to take south. A keen UK racing client was looking for “alternative investments”. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. __________ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States LAWRENCE G. HUTCHINS III, SERGEANT, UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI S. BABU KAZA CHRIS G. OPRISON LtCol, USMCR DLA Piper LLP (US) THOMAS R. FRICTON 500 8th St, NW Captain, USMC Washington DC Counsel of Record Civilian Counsel for U.S. Navy-Marine Corps Petitioner Appellate Defense Division 202-664-6543 1254 Charles Morris St, SE Washington Navy Yard, D.C. 20374 202-685-7291 [email protected] i QUESTION PRESENTED In Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970), this Court held that the collateral estoppel aspect of the Double Jeopardy Clause bars a prosecution that depends on a fact necessarily decided in the defendant’s favor by an earlier acquittal. Here, the Petitioner, Sergeant Hutchins, successfully fought war crime charges at his first trial which alleged that he had conspired with his subordinate Marines to commit a killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim. The members panel (jury) specifically found Sergeant Hutchins not guilty of that aspect of the conspiracy charge, and of the corresponding overt acts and substantive offenses. The panel instead found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the lesser-included offense of conspiring to commit an unlawful killing of a named suspected insurgent leader, and found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the substantive crimes in furtherance of that specific conspiracy. After those convictions were later reversed, Sergeant Hutchins was taken to a second trial in 2015 where the Government once again alleged that the charged conspiracy agreement was for the killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim, and presented evidence of the overt acts and criminal offenses for which Sergeant Hutchins had previously been acquitted.