Military Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moves to Amend HF No. 752 As Follows: Delete Everything After the Enacting Clause and Insert

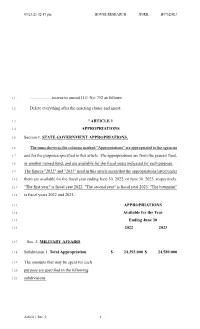

03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 752 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. STATE GOVERNMENT APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the columns marked "Appropriations" are appropriated to the agencies 1.7 and for the purposes specified in this article. The appropriations are from the general fund, 1.8 or another named fund, and are available for the fiscal years indicated for each purpose. 1.9 The figures "2022" and "2023" used in this article mean that the appropriations listed under 1.10 them are available for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2022, or June 30, 2023, respectively. 1.11 "The first year" is fiscal year 2022. "The second year" is fiscal year 2023. "The biennium" 1.12 is fiscal years 2022 and 2023. 1.13 APPROPRIATIONS 1.14 Available for the Year 1.15 Ending June 30 1.16 2022 2023 1.17 Sec. 2. MILITARY AFFAIRS 1.18 Subdivision 1. Total Appropriation $ 24,393,000 $ 24,589,000 1.19 The amounts that may be spent for each 1.20 purpose are specified in the following 1.21 subdivisions. Article 1 Sec. 2. 1 03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 2.1 Subd. 2. Maintenance of Training Facilities 9,772,000 9,772,000 2.2 Subd. 3. General Support 3,507,000 3,633,000 2.3 Subd. 4. Enlistment Incentives 11,114,000 11,114,000 2.4 The appropriations in this subdivision are 2.5 available until June 30, 2025, except that any 2.6 unspent amounts allocated to a program 2.7 otherwise supported by this appropriation are 2.8 canceled to the general fund upon receipt of 2.9 federal funds in the same amount to support 2.10 administration of that program. 2.11 If the amount for fiscal year 2022 is 2.12 insufficient, the amount for 2023 is available 2.13 in fiscal year 2022. -

Il Generale Henri Guisan

Il Generale Henri Guisan Autor(en): Fontana Objekttyp: Obituary Zeitschrift: Rivista militare della Svizzera italiana Band (Jahr): 32 (1960) Heft 3 PDF erstellt am: 26.09.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch RIVISTA MILITARE DELLA SVIZZERA ITALIANA Anno XXXII - Fascicolo III Lugano, maggio - giugno 1960 REDAZIONE : Col. Aldo Camponovo. red. responsabile; Col. Ettore Moccetti; Col. S.M.G. Waldo Riva AMMINISTRAZIONE : Cap. Neno Moroni-Stampa, Lugano Abbonamento: Svizzera un anno fr. 6 - Estero fr. 10,- - C.to ch. post. XI a 53 Inserzioni: Annunci Svizzeri S.A. «ASSA», Lugano, Bellinzona. Locamo e Succ, Il Generale Henri Guisan / Il 7 aprile all'età di 86 anni è deceduto a Pully, dopo breve malattia, il Generale Guisan, Comandante in Capo dell'Esercito Svizzero durante la seconda guerra mondiale. -

Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?

Nebraska Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Article 8 1955 Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness? James W. Hewitt University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation James W. Hewitt, Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?, 34 Neb. L. Rev. 518 (1954) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol34/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 518 NEBRASKA LAW REVIEW CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-UNIFORM CODE OF MILITARY JUSTICE-GENERAL ARTICLE VOID FOR VAGUENESS.? Much has been said or written about the rights of servicemen under the new Uniform Code of Military Justice,1 which is the source of American written military law. Some of the major criticisms of military law have been that it is too harsh, too vague, and too careless of the right to due process of law. A large por tion of this criticism has been leveled at Article 134,2 the general, catch-all article of the Code. Article 134 provides: 3~ Alabama. Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, l\Iaine, l\Iaryland, l\Iasschusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Vermont. South Carolina has the privilege by case decision. See note 4 supra. 1 64 Stat. 107 <1950l, 50 U.S.C. §§ 551-736 (1952). -

Die Hypi-Story Des 19

Dieses Buch erzählt Bankengeschichte am Beispiel eines der führenden regionalen Geld- institute der Schweiz. Die Hypothekarbank Lenzburg hat alle Stürme und Innovationen Die Hypi-Story des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts erlebt und als eigenständiges Institut auch fusionsfrei über- lebt. Damit stellt sie in ihrer Branche bereits eine grosse Ausnahme dar. Gemeinsam mit der fiktiven Erzählerin Verena reisen die Leserin und der Leser durch die Zeit und tauchen in dialogisch vermittelte und szenisch illustrierte Ereignisse ein: Vom landwirtschaftlichen Kredithaus Seien es die Gründungsversammlung, der Run auf die Schalter bei Ausbruch des Ersten zur digitalen Universalbank Weltkriegs, der Bau einer geheimen Tresoranlage in der Innerschweiz, der Kauf des ersten Bankcomputers oder die Selbstbehauptung während dem Bankensterben der 1990er-Jahre. Immer werden leicht verständlich die grossen historischen Entwicklungen am Lenzbur- ger Beispiel gespiegelt. Vom landwirtschaftlichen Kredithaus zur digitalen Universalbank Vom Die Hypi-Story HIER UND JETZT IMPRESSUM Dieses Buch entstand aus Anlass des 150-jährigen Bestehens der Hypothekarbank Lenzburg AG. Lektorat: Urs Voegeli, Hier und Jetzt Layout und Satz: imRaum Furter Handschin Rorato, Baden Schriftart: Sabon Next © 2018 Hier und Jetzt, Verlag für Kultur und Geschichte GmbH, Baden www.hierundjetzt.ch ISBN 978-3-03919-450-6 Die Hypi-Story Vom landwirtschaftlichen Kredithaus zur digitalen Universalbank Fabian Furter Illustrationen von Joe Rohrer und Raphael Gschwind Fotostrecke von Oliver Lang HIER UND JETZT 2018 VORWORT An Oskar Erismann kam vor 150 Jahren keiner vorbei, als er sich als erster Hü- ter der eisernen Geldkiste der Hypi Lenzburg bewarb: Aargauer, Rechtswissen- schaftler und später Eisenbahndirektor bei der Centralbahn, der für seine Kinder Theaterstücke aus der Märchenwelt dichtete. -

Gentlemen Under Fire: the U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 1 June 2008 Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming Elizabeth L. Hillman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Elizabeth L. Hillman, Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming, 26(1) LAW & INEQ. 1 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol26/iss1/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Gentlemen Under Fire: The U.S. Military and "Conduct Unbecoming" Elizabeth L. Hillmant Introduction ..................................................................................1 I. Creating an Officer Class ..................................................10 A. "A Scandalous and Infamous" Manner ...................... 11 B. The "Military Art" and American Gentility .............. 12 C. Continental Army Prosecutions .................................15 II. Building a Profession .........................................................17 A. Colonel Winthrop's Definition ...................................18 B. "A Stable Fraternity" ................................................. 19 C. Old Army Prosecutions ..............................................25 III. Defending a Standing Army ..............................................27 A. "As a Court-Martial May Direct". ............................. 27 B. Democratization and its Discontents ........................ 33 C. Cold War Prosecutions ..............................................36 -

Volume 4 Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2015

TM VOLUME 4 ISSUE 1 FALL/WINTER 2015 National Security Law Journal George Mason University School of Law 3301 Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22201 www.nslj.org © 2015 National Security Law Journal. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Publication Data (Serial) National Security Law Journal. Arlington, Va. : National Security Law Journal, 2013- K14 .N18 ISSN: 2373-8464 Variant title: NSLJ National security—Law and legislation—Periodicals LC control no. 2014202997 (http://lccn.loc.gov/2014202997) Past issues available in print at the Law Library Reading Room of the Library of Congress (Madison, LM201). VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 (FALL/WINTER 2015) ISBN-13: 978-1523203987 ISBN-10: 1523203986 ARTICLES PLANNING FOR CHANGE: BUILDING A FRAMEWORK TO PREDICT FUTURE CHANGES TO THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT Patrick Walsh QUANTUM LAWMAKING: HOW NATIONAL SECURITY LAW HAPPENS WHEN WE’RE NOT LOOKING Jesse Medlong COMMENTS TERROR IN MEXICO: WHY DESIGNATING MEXICAN CARTELS AS TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS EASES PROSECUTION OF DRUG TRAFFICKERS UNDER THE NARCOTERRORISM STATUTE Stephen R. Jackson CYBERSPACE: THE 21ST-CENTURY BATTLEFIELD EXPOSING SOLDIERS, SAILORS, AIRMEN, AND MARINES TO POTENTIAL CIVIL LIABILITIES Molly Picard VOLUME 4 FALL/WINTER 2015 ISSUE 1 PUBLISHED BY GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW Cite as 4 NAT’L SEC. L.J. ___ (2015). The National Security Law Journal (“NSLJ”) is a student-edited legal periodical published twice annually at George Mason University School of Law in Arlington, Virginia. We print timely, insightful scholarship on pressing matters that further the dynamic field of national security law, including topics relating to foreign affairs, homeland security, intelligence, and national defense. Visit our website at www.nslj.org to read our issues online, purchase the print edition, submit an article, learn about our upcoming events, or sign up for our e-mail newsletter. -

Pub. L. 108–136, Div. A, Title V, §509(A)

§ 777a TITLE 10—ARMED FORCES Page 384 Oct. 5, 1999, 113 Stat. 590; Pub. L. 108–136, div. A, for a period of up to 14 days before assuming the title V, § 509(a), Nov. 24, 2003, 117 Stat. 1458; Pub. duties of a position for which the higher grade is L. 108–375, div. A, title V, § 503, Oct. 28, 2004, 118 authorized. An officer who is so authorized to Stat. 1875; Pub. L. 109–163, div. A, title V, wear the insignia of a higher grade is said to be §§ 503(c), 504, Jan. 6, 2006, 119 Stat. 3226; Pub. L. ‘‘frocked’’ to that grade. 111–383, div. A, title V, § 505(b), Jan. 7, 2011, 124 (b) RESTRICTIONS.—An officer may not be au- Stat. 4210.) thorized to wear the insignia for a grade as de- scribed in subsection (a) unless— AMENDMENTS (1) the Senate has given its advice and con- 2011—Subsec. (b)(3)(B). Pub. L. 111–383 struck out sent to the appointment of the officer to that ‘‘and a period of 30 days has elapsed after the date of grade; the notification’’ after ‘‘grade’’. 2006—Subsec. (a). Pub. L. 109–163, § 503(c), inserted ‘‘in (2) the officer has received orders to serve in a grade below the grade of major general or, in the case a position outside the military department of of the Navy, rear admiral,’’ after ‘‘An officer’’ in first that officer for which that grade is authorized; sentence. (3) the Secretary of Defense (or a civilian of- Subsec. (d)(1). -

Military Courts and Article III

Military Courts and Article III STEPHEN I. VLADECK* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................... 934 I. MILITARY JUSTICE AND ARTICLE III: ORIGINS AND CASE LAW ...... 939 A. A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO U.S. MILITARY COURTS ........... 941 1. Courts-Martial ............................... 941 2. Military Commissions ......................... 945 B. THE NORMATIVE JUSTIFICATIONS FOR MILITARY JUSTICE ....... 948 C. THE SUPREME COURT’S CONSTITUTIONAL DEFENSE OF COURTS-MARTIAL ................................. 951 D. THE SUPREME COURT’S CONSTITUTIONAL DEFENSE OF MILITARY COMMISSIONS .................................... 957 II. RECENT EXPANSIONS TO MILITARY JURISDICTION ............... 961 A. SOLORIO AND THE SERVICE-CONNECTION TEST .............. 962 B. ALI AND CHIEF JUDGE BAKER’S BLURRING OF SOLORIO’S BRIGHT LINE .......................................... 963 C. THE MCA AND THE “U.S. COMMON LAW OF WAR” ............ 965 D. ARTICLE III AND THE CIVILIANIZATION OF MILITARY JURISDICTION .................................... 966 E. RECONCILING THE MILITARY EXCEPTION WITH CIVILIANIZATION .................................. 968 * Professor of Law, American University Washington College of Law. © 2015, Stephen I. Vladeck. For helpful discussions and feedback, I owe deep thanks to Zack Clopton, Jen Daskal, Mike Dorf, Gene Fidell, Barry Friedman, Amanda Frost, Dave Glazier, David Golove, Tara Leigh Grove, Ed Hartnett, Harold Koh, Marty Lederman, Peter Margulies, Jim Pfander, Zach Price, Judith Resnik, Gabor Rona, Carlos Va´zquez, Adam Zimmerman, students in my Fall 2013 seminar on military courts, participants in the Hauser Globalization Colloquium at NYU and Northwestern’s Public Law Colloquium, and colleagues in faculty workshops at Cardozo, Cornell, DePaul, FIU, Hastings, Loyola, Rutgers-Camden, and Stanford. Thanks also to Cynthia Anderson, Gabe Auteri, Gal Bruck, Caitlin Marchand, and Pasha Sternberg for research assistance; and to Dean Claudio Grossman for his generous and unstinting support of this project. -

Vorlage Web-Dokus

Inhalt mit Laufzeit Geschichte für Sek I und Sek II Deutsch Der General Die Lebensgeschichte Henri Guisans 55:15 Minuten 00:00 Kurz vor Ausbruch des Zweiten Weltkrieges wählt die Bun- desversammlung Guisan zum General. 04:19 Im September 1939 erklärt Hitler Polen den Krieg. Darauf rücken 600'000 Schweizer Männer bei der Generalmobilmachung in den Aktivdienst ein. 07:01 General Henri Guisan kommt 1874 als Sohn eines Landarz- tes zur Welt. Er schliesst erfolgreich sein Agronomiestudium ab. Den Militärdienst leistet er bei der Kavallerie. Bereits während des Ersten Weltkriegs ist er Mitglied des Generalstabs. 11:56 Guisans politische Einstellung ist rechts-konservativ. Deshalb pflegt er enge Verbindungen zur liberalen Partei. Während des lan- desweiten Generalstreiks 1918 leitet Guisan ein Regiment in Zürich. 13:11 1934 trifft er Benito Mussolini, zu dem er ein freundschaftli- ches Verhältnis aufbaut. Guisan hofft, dass Mussolini Hitler von ei- nem Angriff auf die Schweiz abhalten kann. Sein erstes Hauptquar- tier ist das Schloss Gümligen. Mitarbeiter des persönlichen Stabs steuern den Personenkult um Guisan. 19:18 Anscheinend verspricht die französische Militärspitze Hilfe im Falle eines Angriffs von Deutschland. Die Eroberung von Paris zer- stört jedoch diese Hoffnung. Einzig Grossbritannien leistet Hitler noch Widerstand. In dieser Phase ist das Verhältnis zwischen Bun- despräsident Pilet-Golaz und Guisan angespannt. 23:47 Guisan beordert 650 Offiziere aufs Rütli zum Rapport. Dort bekräftigt er den Verteidigungswillen. Mit dem Rückzug ins Réduit konzentriert er seine Verteidigung auf die Alpenregion. Haben die Deutschen deshalb nicht angegriffen? Historiker bezweifeln heute diese Theorie. 28:07 Viele Flüchtlinge suchen während dieser Zeit Schutz in der Schweiz. -

Gotthard Panorama Express. Sales Manual 2021

Gotthard Panorama Express. Sales Manual 2021. sbb.ch/en/gotthard-panorama-express Enjoy history on the Gotthard Panorama Express to make travel into an experience. This is a unique combination of boat and train journeys on the route between Central Switzerland and Ticino. Der Gotthard Panorama Express: ì will operate from 1 May – 18 October 2021 every Tuesday to Sunday (including national public holidays) ì travels on the line from Lugano to Arth-Goldau in three hours. There are connections to the Mount Rigi Railways, the Voralpen-Express to Lucerne and St. Gallen and long-distance trains towards Lucerne/ Basel, Zurich or back to Ticino via the Gotthard Base Tunnel here. ì with the destination Arth-Goldau offers, varied opportunities; for example, the journey can be combined with an excursion via cog railway to the Rigi and by boat from Vitznau. ì runs as a 1st class panorama train with more capacity. There is now a total of 216 seats in four panorama coaches. The popular photography coach has been retained. ì requires a supplement of CHF 16 per person for the railway section. The supplement includes the compulsory seat reservation. ì now offers groups of ten people or more a group discount of 30% (adjustment of group rates across the whole of Switzerland). 2 3 Table of contents. Information on the route 4 Route highlights 4–5 Journey by boat 6 Journey on the panorama train 7 Timetable 8 Train composition 9 Fleet of ships 9 Prices and supplements 12 Purchase procedure 13 Services 14 Information for tour operators 15 Team 17 Treno Gottardo 18 Grand Train Tour of Switzerland 19 2 3 Information on the route. -

Departure Without Destination. Annemarie Schwarzenbach As Photographer 18.09.20–03.01.21

Exhibition Guide Founded by Maurice E. and Martha Müller and the heirs of Paul Klee Departure without Destination. Annemarie Schwarzenbach as photographer 18.09.20–03.01.21 Table of contents 1 “A Love for Europe” 7 2 “Little Encounters” 12 3 The “New Earth” 15 4 “Beyond New York” 21 5 “Between Continents” 28 6 “The Happy Valley” 31 Biography 36 3 Floorplan 3 4 5 LOUNGE 2 6 1 4 Writer, journalist, photographer, traveller, cosmopolitan: Annemarie Schwarzenbach is one of the most dazzling and contradictory figures in modern Swiss cultural history. Schwarzenbach saw herself primarily as a writer. Yet she was also a pioneer of photojournalism in Switzerland. Around 300 of her texts appeared in Swiss magazines and newspapers during her lifetime. From 1933, they were increasingly accompanied by her own pho- tographs. However, since the majority of these images remained unpublished, the quality and scope of her work as a photographer has been relatively unknown until recently. Most of Schwarzenbach’s photographs were taken during her travels, which between 1933 and 1942 took her across Europe, to the Near East and Central Asia, to the United States and Central and North Africa. Her work as a journalist, but also her upper class background and her status as the wife of a diplomat granted her an extraordinary freedom of travel for the period. Her images and writings are closely intertwined and document the upheavals, tensions, and conflicts of the period leading up to World War II: the consequences of the Great Depression, the hope for social progress, the threat of National Socialism, the effects of modernization and industrialization, or the European fascination with the “orient”. -

Chiasso 1945

Chiasso 1945 Objekttyp: Group Zeitschrift: Rivista militare della Svizzera italiana Band (Jahr): 82 (2010) Heft 3 PDF erstellt am: 03.10.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch SPECIALE Chiasso 1945 La relazione del dott. Jürg Stüssi-Lauterburg, tenuta a Chiasso il 28 aprile scorso nell’ambito della cerimonia ufficiale, conclude il capitolo che la RMSI ha dedicato ai “Fatti di Chiasso” e al colonnello Mario Martinoni. Ci congratuliamo con il Comune di Chiasso e il Console generale di Svizzera a Milano David Vogelsanger per la lodevole iniziativa che ha dato il giusto risalto a un periodo particolare della storia militare ticinese.