Criminal Law Deskbook, Volume II, Crimes and Defenses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ILRC | Selected Immigration Defenses for Selected California Crimes

Defenses for California Crimes Immigrant Legal Resource Center August 2018 www.ilrc.org SELECTED IMMIGRATION DEFENSES FOR SELECTED CALIFORNIA CRIMES Immigrant Legal Resource Center August 2018 This article is an updated guide to selected California offenses that discusses precedent decisions and other information showing that the offenses avoid at least some adverse immigration consequences. This is not a complete analysis of each offense. It does not note adverse immigration consequence that may apply. How defense counsel can use this article. Criminal defense counsel who negotiate a plea that is discussed in this article should provide the noncitizen defendant with a copy of the relevant pages containing the immigration analysis. In the event that the noncitizen defendant ends up in removal proceedings, presenting that summary of the analysis may be their best access to an affirmative defense against deportation, because the vast majority of immigrants in deportation proceedings are unrepresented by counsel. Because ICE often confiscates documents from detainees, it is a good idea to give a second copy of the summary to the defendant’s immigration attorney (if any), or family or friend, for safekeeping. Again, this article does not show all immigration consequences of offenses. For further information and analysis of other offenses, defense counsel also should consult the California Quick Reference Chart; go to www.ilrc.org/chart. As always, advise noncitizen defendants not to discuss their place of birth or undocumented immigration status with ICE or any other law enforcement representative. See information at www.ilrc.org/red-cards. The fact that the person gives an immigration judge or officer this summary should not be taken as an admission of alienage. -

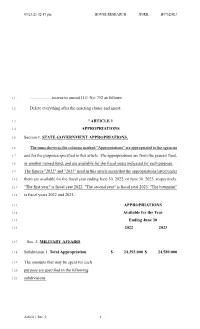

Moves to Amend HF No. 752 As Follows: Delete Everything After the Enacting Clause and Insert

03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 752 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. STATE GOVERNMENT APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the columns marked "Appropriations" are appropriated to the agencies 1.7 and for the purposes specified in this article. The appropriations are from the general fund, 1.8 or another named fund, and are available for the fiscal years indicated for each purpose. 1.9 The figures "2022" and "2023" used in this article mean that the appropriations listed under 1.10 them are available for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2022, or June 30, 2023, respectively. 1.11 "The first year" is fiscal year 2022. "The second year" is fiscal year 2023. "The biennium" 1.12 is fiscal years 2022 and 2023. 1.13 APPROPRIATIONS 1.14 Available for the Year 1.15 Ending June 30 1.16 2022 2023 1.17 Sec. 2. MILITARY AFFAIRS 1.18 Subdivision 1. Total Appropriation $ 24,393,000 $ 24,589,000 1.19 The amounts that may be spent for each 1.20 purpose are specified in the following 1.21 subdivisions. Article 1 Sec. 2. 1 03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 2.1 Subd. 2. Maintenance of Training Facilities 9,772,000 9,772,000 2.2 Subd. 3. General Support 3,507,000 3,633,000 2.3 Subd. 4. Enlistment Incentives 11,114,000 11,114,000 2.4 The appropriations in this subdivision are 2.5 available until June 30, 2025, except that any 2.6 unspent amounts allocated to a program 2.7 otherwise supported by this appropriation are 2.8 canceled to the general fund upon receipt of 2.9 federal funds in the same amount to support 2.10 administration of that program. 2.11 If the amount for fiscal year 2022 is 2.12 insufficient, the amount for 2023 is available 2.13 in fiscal year 2022. -

Attempt: an Overview of Federal Criminal Law

Attempt: An Overview of Federal Criminal Law Charles Doyle Senior Specialist in American Public Law April 6, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42001 Attempt: An Overview of Federal Criminal Law Summary It is not a crime to attempt to commit most federal offenses. Unlike state law, federal law has no generally applicable crime of attempt. Congress, however, has outlawed the attempt to commit a substantial number of federal crimes on an individual basis. In doing so, it has proscribed the attempt, set its punishment, and left to the federal courts the task of further developing the law in the area. The courts have identified two elements in the crime of attempt: an intent to commit the underlying substantive offense and some substantial step towards that end. The point at which a step may be substantial is not easily discerned; but it seems that the more serious and reprehensible the substantive offense, the less substantial the step need be. Ordinarily, the federal courts accept neither impossibility nor abandonment as an effective defense to a charge of attempt. Attempt and the substantive offense carry the same penalties in most instances. A defendant may not be convicted of both the substantive offense and the attempt to commit it. Commission of the substantive offense, however, is neither a prerequisite for, nor a defense against, an attempt conviction. Whether a defendant may be guilty of an attempt to attempt to commit a federal offense is often a matter of statutory construction. Attempts to conspire and attempts to aid and abet generally present less perplexing questions. -

Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?

Nebraska Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Article 8 1955 Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness? James W. Hewitt University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation James W. Hewitt, Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?, 34 Neb. L. Rev. 518 (1954) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol34/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 518 NEBRASKA LAW REVIEW CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-UNIFORM CODE OF MILITARY JUSTICE-GENERAL ARTICLE VOID FOR VAGUENESS.? Much has been said or written about the rights of servicemen under the new Uniform Code of Military Justice,1 which is the source of American written military law. Some of the major criticisms of military law have been that it is too harsh, too vague, and too careless of the right to due process of law. A large por tion of this criticism has been leveled at Article 134,2 the general, catch-all article of the Code. Article 134 provides: 3~ Alabama. Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, l\Iaine, l\Iaryland, l\Iasschusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Vermont. South Carolina has the privilege by case decision. See note 4 supra. 1 64 Stat. 107 <1950l, 50 U.S.C. §§ 551-736 (1952). -

Supreme Court No. 97434-9 in the SUPREME COURT of the STATE

FILED SUPREME COURT STATE OF WASHINGTON 712212019 2:43 PM BY SUSAN L. CARLSON CLERK Supreme Court No. 97434-9 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON STATE OF WASHINGTON, Respondent v. CLARISSA ALISHA LOPEZ, Petitioner PETITION FOR REVIEW _____________________________________________________ Marie J. Trombley, WSBA 41410 Counsel for Petitioner Lopez PO Box 829 Graham, WA 253-445-7920 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IDENTITY OF PETITIONER ..................................................... 1 II. DECISION OF LOWER COURT .............................................. 1 III. ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW ...................................... 1 A. Under State v. Smith, 145 Wn.App. 268, 187 P.3d 768 (2008), the poLice may not LawfuLLy seize and detain occupants of a car for investigation who appear outside the residence where officers are executing a search warrant, in which neither the car nor the occupant was named. Did the triaL court wrongLy deny a motion to suppress under facts virtuaLLy identicaL to Smith? B. Does the ruLing by the Court of AppeaLs regarding doubLe jeopardy confLict with State v. Adel, 136 Wn.2d 629, 965 P.2d 1072 (1998), and State v. O’Connor, 87 Wn.App. 119, 940 P.2d 675 (1997)? IV. STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................... 2 V. ARGUMENT WHY REVIEW SHOULD BE ACCEPTED .......... 5 A. PoLice UnLawfuLLy Seized Ms. Lopez. .................................... 6 B. PoLice Officers May Not LawfuLLy Seize And Detain For Investigation Occupants Of A Car Who Arrive In The Driveway Of A Residence Where Officers Are Executing A Search Warrant When Neither The Vehicle Nor The Occupants Were Named In The Warrant. …………………...8 C. Ms. Lopez’s Right To Be Free From DoubLe Jeopardy Was VioLated…………………………………………………………10 VI. -

Presidential Obstruction of Justice Daniel Hemel

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers Working Papers 2017 Presidential Obstruction of Justice Daniel Hemel Eric A. Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ public_law_and_legal_theory Part of the Law Commons Chicago Unbound includes both works in progress and final versions of articles. Please be aware that a more recent version of this article may be available on Chicago Unbound, SSRN or elsewhere. Recommended Citation Hemel, Daniel and Posner, Eric A., "Presidential Obstruction of Justice" (2017). Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers. 665. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/public_law_and_legal_theory/665 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Working Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESIDENTIAL OBSTRUCTION OF JUSTICE Daniel J. Hemel* Eric A. Posner** Federal obstruction of justice statutes bar anyone from interfering with law enforcement based on a “corrupt” motive. But what about the president of the United States? The president is vested with “executive power,” which includes the power to control federal law enforcement. A possible view is that the statutes do not apply to the president because if they did they would violate the president’s constitutional power. However, we argue that the obstruction of justice statutes are best interpreted to apply to the president, and that the president obstructs justice when his motive for intervening in an investigation is to further personal, pecuniary, or narrowly partisan interests, rather than to advance the public good. -

History of Criminalization (November 2012)

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Conferences and Workshops Conferences, Workshops, and Seminars 11-2012 History of Criminalization (November 2012) Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ nathanson_conferences Recommended Citation "History of Criminalization (November 2012)" (2012). Conferences and Workshops. 20. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/nathanson_conferences/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences, Workshops, and Seminars at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conferences and Workshops by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. Draft “Subverting the Settled Order of Things”: Sedition and Crimes against the State I. The Rise and Fall of Sedition In the introduction to Leviathan, where he developed an extended metaphor comparing parts of Leviathan, or the artificial man, to the human body, Thomas Hobbes described sedition as sickness, a sign of ill health in the body politic.1 This understanding of sedition, between concord and civil war, indicates the seriousness of the threat which sedition was understood to pose to the ongoing life and healthy functioning of the state. The criminal law, as a system of rewards and punishments, was described as the ‘nerves’ of the Leviathan by which means men were moved to perform their duty, and so it is not surprising to find that sedition – as a form of treason or as a description of other kinds of conduct (conspiracy, libel, speech) directed against established authority – figured large in early modern systems of criminal law. This might be contrasted with a modern understanding of the importance of dissent or disagreement to a properly functioning political order, and the modern distrust of political and legal orders where dissent is stifled. -

Gentlemen Under Fire: the U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 1 June 2008 Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming Elizabeth L. Hillman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Elizabeth L. Hillman, Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming, 26(1) LAW & INEQ. 1 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol26/iss1/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Gentlemen Under Fire: The U.S. Military and "Conduct Unbecoming" Elizabeth L. Hillmant Introduction ..................................................................................1 I. Creating an Officer Class ..................................................10 A. "A Scandalous and Infamous" Manner ...................... 11 B. The "Military Art" and American Gentility .............. 12 C. Continental Army Prosecutions .................................15 II. Building a Profession .........................................................17 A. Colonel Winthrop's Definition ...................................18 B. "A Stable Fraternity" ................................................. 19 C. Old Army Prosecutions ..............................................25 III. Defending a Standing Army ..............................................27 A. "As a Court-Martial May Direct". ............................. 27 B. Democratization and its Discontents ........................ 33 C. Cold War Prosecutions ..............................................36 -

Volume 4 Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2015

TM VOLUME 4 ISSUE 1 FALL/WINTER 2015 National Security Law Journal George Mason University School of Law 3301 Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22201 www.nslj.org © 2015 National Security Law Journal. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Publication Data (Serial) National Security Law Journal. Arlington, Va. : National Security Law Journal, 2013- K14 .N18 ISSN: 2373-8464 Variant title: NSLJ National security—Law and legislation—Periodicals LC control no. 2014202997 (http://lccn.loc.gov/2014202997) Past issues available in print at the Law Library Reading Room of the Library of Congress (Madison, LM201). VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 (FALL/WINTER 2015) ISBN-13: 978-1523203987 ISBN-10: 1523203986 ARTICLES PLANNING FOR CHANGE: BUILDING A FRAMEWORK TO PREDICT FUTURE CHANGES TO THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT Patrick Walsh QUANTUM LAWMAKING: HOW NATIONAL SECURITY LAW HAPPENS WHEN WE’RE NOT LOOKING Jesse Medlong COMMENTS TERROR IN MEXICO: WHY DESIGNATING MEXICAN CARTELS AS TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS EASES PROSECUTION OF DRUG TRAFFICKERS UNDER THE NARCOTERRORISM STATUTE Stephen R. Jackson CYBERSPACE: THE 21ST-CENTURY BATTLEFIELD EXPOSING SOLDIERS, SAILORS, AIRMEN, AND MARINES TO POTENTIAL CIVIL LIABILITIES Molly Picard VOLUME 4 FALL/WINTER 2015 ISSUE 1 PUBLISHED BY GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW Cite as 4 NAT’L SEC. L.J. ___ (2015). The National Security Law Journal (“NSLJ”) is a student-edited legal periodical published twice annually at George Mason University School of Law in Arlington, Virginia. We print timely, insightful scholarship on pressing matters that further the dynamic field of national security law, including topics relating to foreign affairs, homeland security, intelligence, and national defense. Visit our website at www.nslj.org to read our issues online, purchase the print edition, submit an article, learn about our upcoming events, or sign up for our e-mail newsletter. -

SECOND CONCURRENCE SCHALLER, J., Concurring

****************************************************** The ``officially released'' date that appears near the beginning of each opinion is the date the opinion will be published in the Connecticut Law Journal or the date it was released as a slip opinion. The operative date for the beginning of all time periods for filing postopinion motions and petitions for certification is the ``officially released'' date appearing in the opinion. In no event will any such motions be accepted before the ``officially released'' date. All opinions are subject to modification and technical correction prior to official publication in the Connecti- cut Reports and Connecticut Appellate Reports. In the event of discrepancies between the electronic version of an opinion and the print version appearing in the Connecticut Law Journal and subsequently in the Con- necticut Reports or Connecticut Appellate Reports, the latest print version is to be considered authoritative. The syllabus and procedural history accompanying the opinion as it appears on the Commission on Official Legal Publications Electronic Bulletin Board Service and in the Connecticut Law Journal and bound volumes of official reports are copyrighted by the Secretary of the State, State of Connecticut, and may not be repro- duced and distributed without the express written per- mission of the Commission on Official Legal Publications, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. ****************************************************** CONNECTICUT COALITION FOR JUSTICE IN EDUCATION FUNDING, INC. v. RELLÐSECOND -

State V. Santiago

****************************************************** The ``officially released'' date that appears near the beginning of each opinion is the date the opinion will be published in the Connecticut Law Journal or the date it was released as a slip opinion. The operative date for the beginning of all time periods for filing postopinion motions and petitions for certification is the ``officially released'' date appearing in the opinion. In no event will any such motions be accepted before the ``officially released'' date. All opinions are subject to modification and technical correction prior to official publication in the Connecti- cut Reports and Connecticut Appellate Reports. In the event of discrepancies between the electronic version of an opinion and the print version appearing in the Connecticut Law Journal and subsequently in the Con- necticut Reports or Connecticut Appellate Reports, the latest print version is to be considered authoritative. The syllabus and procedural history accompanying the opinion as it appears on the Commission on Official Legal Publications Electronic Bulletin Board Service and in the Connecticut Law Journal and bound volumes of official reports are copyrighted by the Secretary of the State, State of Connecticut, and may not be repro- duced and distributed without the express written per- mission of the Commission on Official Legal Publications, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. ****************************************************** STATE OF CONNECTICUT v. VICTOR SANTIAGO (SC 17381) Sullivan, C. J., and Borden, Norcott, Palmer and Zarella, Js. Argued May 18Ðofficially released August 30, 2005 Jeffrey C. Kestenband, with whom was William H. Paetzold, for the appellant (defendant). John A. East III, senior assistant state's attorney, with whom, on the brief, was Timothy J. -

Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

William & Mary Law Review Volume 37 (1995-1996) Issue 1 Article 10 October 1995 Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial Alan L. Adlestein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Alan L. Adlestein, Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial, 37 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 199 (1995), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss1/10 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr CONFLICT OF THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS WITH LESSER OFFENSES AT TRIAL ALAN L. ADLESTEIN I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 200 II. THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS AND LESSER OFFENSES-DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONFLICT ........ 206 A. Prelude: The Problem of JurisdictionalLabels ..... 206 B. The JurisdictionalLabel and the CriminalStatute of Limitations ................ 207 C. The JurisdictionalLabel and the Lesser Offense .... 209 D. Challenges to the Jurisdictional Label-In re Winship, Keeble v. United States, and United States v. Wild ..................... 211 E. Lesser Offenses and the Supreme Court's Capital Cases- Beck v. Alabama, Spaziano v. Florida, and Schad v. Arizona ........................... 217 1. Beck v. Alabama-LegislativePreclusion of Lesser Offenses ................................ 217 2. Spaziano v. Florida-Does the Due Process Clause Require Waivability? ....................... 222 3. Schad v. Arizona-The Single Non-Capital Option ....................... 228 F. The Conflict Illustrated in the Federal Circuits and the States ....................... 230 1. The Conflict in the Federal Circuits ........... 232 2. The Conflict in the States .................. 234 III.