Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INVESTIGATIVE REPORT Lori Torres, Inspector General

INVESTIGATIVE REPORT Lori Torres, Inspector General OFFICE: INDIANA BUREAU OF MOTOR VEHICLES TITLE: FORGERY; PERJURY; THEFT CASE ID: 2017-12-0293 DATE: August 30, 2018 Inspector General Staff Attorney Kelly Elliott, after an investigation by Special Agent Mark Mitchell, reports as follows: The Indiana General Assembly charged the Office of Inspector General (OIG) with addressing fraud, waste, abuse, and wrongdoing in the executive branch of state government. IC 4-2-7-2(b). The OIG also investigates criminal activity and ethics violations by state workers. IC 4-2-7-3. The OIG may recommend policies and carry out other activities designed to deter, detect, and eradicate fraud, waste, abuse, mismanagement, and misconduct in state government. IC 4-2- 7-3(2). On March 23, 2017, the OIG received a complaint from the Indiana Bureau of Motor Vehicles (BMV) that alleged a former BMV employee, Richard Pringle, submitted false information to the BMV on personal certificate of title applications. OIG Special Agent Mark Mitchell conducted an investigation into this matter. Through the course of his investigation, Special Agent Mitchell interviewed Pringle and reviewed documentation received from BMV, including their internal investigation report on this matter. According to BMV’s investigative report of the allegations against Pringle, BMV found that Pringle submitted an application for a 1997 GMC Yukon in October 2016 that listed a sale price 1 that was different from the price the seller of the vehicle stated they sold it. At the conclusion of their investigation, BMV terminated Pringle’s employment in or around March 2017. Special Agent Mitchell reviewed the BMV certificate of title application for the 1997 GMC Yukon. -

Cops Or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dimitri Epstein, Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epstein: Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute App COPS OR ROBBERS? HOW GEORGIA'S DEFENSE OF HABITATION STATUTE APPLIES TO NONO- KNOCK RAIDS BY POLICE Dimitri Epstein*Epstein * INTRODUCTION Late in the fall of 2006, the city of Atlanta exploded in outrage when Kathryn Johnston, a ninety-two-year old woman, died in a shoot-out with a police narcotics team.team.' 1 The police used a "no"no- knock" search warrant to break into Johnston's home unannounced.22 Unfortunately for everyone involved, Ms. Johnston kept an old revolver for self defense-not a bad strategy in a neighborhood with a thriving drug trade and where another elderly woman was recently raped.33 Probably thinking she was being robbed, Johnston managed to fire once before the police overwhelmed her with a "volley of thirty-nine" shots, five or six of which proved fatal.fata1.44 The raid and its aftermath appalled the nation, especially when a federal investigation exposed the lies and corruption leading to the incident. -

CONFERENCE COMMITTEE REPORT BRIEF HOUSE BILL NO. 2026 Brief* HB 2026 Would Establish a Certified Drug Abuse Treatment Program Fo

SESSION OF 2021 CONFERENCE COMMITTEE REPORT BRIEF HOUSE BILL NO. 2026 As Agreed to April 8, 2021 Brief* HB 2026 would establish a certified drug abuse treatment program for certain persons who have entered into a diversion agreement pursuant to a memorandum of understanding and amend law related to supervision of offenders and the administration of certified drug abuse treatment programs. It also would amend law to change penalties for crimes involving riot in a correctional facility and unlawfully tampering with an electronic monitoring device. Certified Drug Abuse Treatment Program—Divertees The bill would establish a certified drug abuse treatment program (program) for certain persons who have entered into a diversion agreement (divertees) pursuant to a memorandum of understanding (MOU). The bill would allow eligibility for participation in a program for offenders who have entered into a diversion agreement in lieu of further criminal proceedings on and after July 1, 2021, for persons who have been charged with felony possession of a controlled substance and whose criminal history score is C or lower with no prior felony drug convictions. ____________________ *Conference committee report briefs are prepared by the Legislative Research Department and do not express legislative intent. No summary is prepared when the report is an agreement to disagree. Conference committee report briefs may be accessed on the Internet at http://www.kslegislature.org/klrd [Note: Under continuing law, Kansas’ sentencing guidelines for drug crimes utilize a grid containing the crime severity level (1 to 5, 1 being the highest severity) and the offender’s criminal history score (A to I, A being the highest criminal history score) to determine the presumptive sentence for an offense. -

Crimes Act 2016

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Crimes Act 2016 ______________________________ Act No. 18 of 2016 ______________________________ TABLE OF PROVISIONS PART 1 – PRELIMINARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1 Short title .................................................................................................... 1 2 Commencement ......................................................................................... 1 3 Application ................................................................................................. 1 4 Codification ................................................................................................ 1 5 Standard geographical jurisdiction ............................................................. 2 6 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—ship or aircraft outside Nauru ......................... 2 7 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—transnational crime ......................................... 4 PART 2 – INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................ 6 8 Definitions .................................................................................................. 6 9 Definition of consent ................................................................................ 13 PART 3 – PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY ................................................. 14 DIVISION 3.1 – PURPOSE AND APPLICATION ................................................................. 14 10 Purpose -

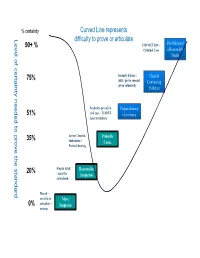

Level of Certainty Needed to Prove the Standard

% certainty Curved Line represents Level of certainty needed to prove the standard needed toprove of certainty Level difficulty to prove or articulate 90+ % CONVICTION – Proof Beyond Criminal Case a Reasonable Doubt 75% Insanity defense / Clear & alibi / prove consent Convincing given voluntarily Evidence Needed to prevail in Preponderance 51% civil case – LIABLE of evidence Asset Forfeiture 35% Arrest / Search / Probable Indictment / Cause Pretrial hearing 20% Stop & Frisk Reasonable – must be Suspicion articulated Hunch – not able to Mere 0% articulate / Suspicion no stop Mere Suspicion – This term is used by the courts to refer to a hunch or intuition. We all experience this in everyday life but it is NOT enough “legally” to act on. It does not mean than an officer cannot observe the activity or person further without making contact. Mere suspicion cannot be articulated using any reasonably accepted facts or experiences. An officer may always make a consensual contact with a citizen without any justification. The officer will however have not justification to stop or hold a person under this situation. One might say something like, “There is just something about him that I don’t trust”. “I can’t quit put my finger on what it is about her.” “He looks out of place.” Reasonable Suspicion – Stop, Frisk for Weapons, *(New) Search of vehicle incident to arrest under Arizona V. Gant. The landmark case for reasonable suspicion is Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) This level of proof is the justification police officers use to stop a person under suspicious circumstances (e.g. a person peaking in a car window at 2:00am). -

Criminal Liability of Corporations

THE LAW COMMISSION WORKING PAPER NO. 44 SECOND PROGRAMME, ITEM XVIII CODIFICATION OF THE CRIMINAL LAW \ GENERAL PRINCIPLES CRIMINAL LIABILITY OF CORPORATIONS LAW COhlMISSION INTRODUCTION 1. This Paper is the third in a series prepared by the Working Party' assisting the Law Commission in the examination of the general principles of the criminal law which is designed as a basis upon which to seek the views of those concerned with the criminal law. It is being issued for con- sultation simultaneously with Working Paper No. 43. 2 2. As the introduction to Working Paper No. 43 explains, extended consideration of the liability of corporations outside the context of criminal liability for another's acts was thought necessary because of particular problems in the field of the criminal law to which corporations give rise. Those problems also dictated the form which the present Paper takes. Unlike the two previous Papers in this series, it contains, not a series of propositions with illustrations and commentary, but in the first place an exposition of the present state of the law and its development togetver with a survey of the current position abroad and, secondly, an examination of the various possible bases of corporate liability followed by a discussion of the social and policy factors which may favour the choice of one or other of these bases for the future. - -- 1. For membership; see p. (3). 2, "Parties, complicity and liability for the acts of nnothrr". 3. The Law Commission agrees with the views expressed by the Working Party that the subject of corporate criminal liability requires treatment separate from that accorded to the subject of complicity in general and that such treatment may best take the form of an exposition of the problems such as the present Paper adopts, The Commission therefore welcomes the Paper for purposes of consultation and, in accordance with its usual policy, is publishing it with an invitation to com- mcnt upon its generai approach and conclusions. -

Competing Theories of Blackmail: an Empirical Research Critique of Criminal Law Theory

Competing Theories of Blackmail: An Empirical Research Critique of Criminal Law Theory Paul H. Robinson,* Michael T. Cahill** & Daniel M. Bartels*** The crime of blackmail has risen to national media attention because of the David Letterman case, but this wonderfully curious offense has long been the favorite of clever criminal law theorists. It criminalizes the threat to do something that would not be criminal if one did it. There exists a rich liter- ature on the issue, with many prominent legal scholars offering their accounts. Each theorist has his own explanation as to why the blackmail offense exists. Most theories seek to justify the position that blackmail is a moral wrong and claim to offer an account that reflects widely shared moral intuitions. But the theories make widely varying assertions about what those shared intuitions are, while also lacking any evidence to support the assertions. This Article summarizes the results of an empirical study designed to test the competing theories of blackmail to see which best accords with pre- vailing sentiment. Using a variety of scenarios designed to isolate and test the various criteria different theorists have put forth as “the” key to blackmail, this study reveals which (if any) of the various theories of blackmail proposed to date truly reflects laypeople’s moral judgment. Blackmail is not only a common subject of scholarly theorizing but also a common object of criminal prohibition. Every American jurisdiction criminalizes blackmail, although there is considerable variation in its formulation. The Article reviews the American statutes and describes the three general approaches these provisions reflect. -

The Unnecessary Crime of Conspiracy

California Law Review VOL. 61 SEPTEMBER 1973 No. 5 The Unnecessary Crime of Conspiracy Phillip E. Johnson* The literature on the subject of criminal conspiracy reflects a sort of rough consensus. Conspiracy, it is generally said, is a necessary doctrine in some respects, but also one that is overbroad and invites abuse. Conspiracy has been thought to be necessary for one or both of two reasons. First, it is said that a separate offense of conspiracy is useful to supplement the generally restrictive law of attempts. Plot- ters who are arrested before they can carry out their dangerous schemes may be convicted of conspiracy even though they did not go far enough towards completion of their criminal plan to be guilty of attempt.' Second, conspiracy is said to be a vital legal weapon in the prosecu- tion of "organized crime," however defined.' As Mr. Justice Jackson put it, "the basic conspiracy principle has some place in modem crimi- nal law, because to unite, back of a criniinal purpose, the strength, op- Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley. A.B., Harvard Uni- versity, 1961; J.D., University of Chicago, 1965. 1. The most cogent statement of this point is in Note, 14 U. OF TORONTO FACULTY OF LAW REv. 56, 61-62 (1956): "Since we are fettered by an unrealistic law of criminal attempts, overbalanced in favour of external acts, awaiting the lit match or the cocked and aimed pistol, the law of criminal conspiracy has been em- ployed to fill the gap." See also MODEL PENAL CODE § 5.03, Comment at 96-97 (Tent. -

BAIL JUMPING in the THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action Or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on Or After Sept

BAIL JUMPING IN THE THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on or after Sept. 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Bail Jumping in the Third Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of Bail Jumping in the Third Degree when by court order he or she has been released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty, either upon bail or upon his or her own recognizance, upon condition that he or she will subsequently appear personally in connection with a criminal action or proceeding1, and when he or she does not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. In order for you to find the defendant guilty of this crime, the People are required to prove, from all of the evidence in the case, beyond a reasonable doubt, both of the following two elements: 1. That the defendant, (defendant’s name) was, by court order, released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty upon bail [or upon his/her own recognizance] upon condition that he/she would subsequently appear personally on (date) in (county) in connection with a criminal action or proceeding; and 2. That the defendant did not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. Note: If the affirmative defense does not apply, conclude as follows: If you find the People have proven beyond a reasonable doubt both of those elements, you must find the defendant guilty 1 If in issue, define criminal action or criminal proceeding in accordance with CPL 1.20(16) and (18). -

Virginia Model Jury Instructions – Criminal

Virginia Model Jury Instructions – Criminal Release 20, September 2019 NOTICE TO USERS: THE FOLLOWING SET OF UNANNOTATED MODEL JURY INSTRUCTIONS ARE BEING MADE AVAILABLE WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER, MATTHEW BENDER & COMPANY, INC. PLEASE NOTE THAT THE FULL ANNOTATED VERSION OF THESE MODEL JURY INSTRUCTIONS IS AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE FROM MATTHEW BENDER® BY WAY OF THE FOLLOWING LINK: https://store.lexisnexis.com/categories/area-of-practice/criminal-law-procedure- 161/virginia-model-jury-instructions-criminal-skuusSku6572 Matthew Bender is a registered trademark of Matthew Bender & Company, Inc. Instruction No. 2.050 Preliminary Instructions to Jury Members of the jury, the order of the trial of this case will be in four stages: 1. Opening statements 2. Presentation of the evidence 3. Instructions of law 4. Final argument After the conclusion of final argument, I will instruct you concerning your deliberations. You will then go to your room, select a foreperson, deliberate, and arrive at your verdict. Opening Statements First, the Commonwealth's attorney may make an opening statement outlining his or her case. Then the defendant's attorney also may make an opening statement. Neither side is required to do so. Presentation of the Evidence [Second, following the opening statements, the Commonwealth will introduce evidence, after which the defendant then has the right to introduce evidence (but is not required to do so). Rebuttal evidence may then be introduced if appropriate.] [Second, following the opening statements, the evidence will be presented.] Instructions of Law Third, at the conclusion of all evidence, I will instruct you on the law which is to be applied to this case. -

False Statements and Perjury: a Sketch of Federal Criminal Law

False Statements and Perjury: A Sketch of Federal Criminal Law Charles Doyle Senior Specialist in American Public Law May 11, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov 98-807 False Statements and Perjury: A Sketch of Federal Criminal Law Summary Federal courts, Congress, and federal agencies rely upon truthful information in order to make informed decisions. Federal law therefore proscribes providing the federal courts, Congress, or federal agencies with false information. The prohibition takes four forms: false statements; perjury in judicial proceedings; perjury in other contexts; and subornation of perjury. Section 1001 of Title 18 of the United States Code, the general false statement statute, outlaws material false statements in matters within the jurisdiction of a federal agency or department. It reaches false statements in federal court and grand jury sessions as well as congressional hearings and administrative matters but not the statements of advocates or parties in court proceedings. Under Section 1001, a statement is a crime if it is false regardless of whether it is made under oath. In contrast, an oath is the hallmark of the three perjury statutes in Title 18. The oldest, Section 1621, condemns presenting material false statements under oath in federal official proceedings. Section 1623 of the same title prohibits presenting material false statements under oath in federal court proceedings, although it lacks some of Section 1621’s traditional procedural features, such as a two-witness requirement. Subornation of perjury, barred in Section 1622, consists of inducing another to commit perjury. All four sections carry a penalty of imprisonment for not more than five years, although Section 1001 is punishable by imprisonment for not more than eight years when the offense involves terrorism or one of the various federal sex offenses. -

In Praise of Statutes of Limitations in Sex Offense Cases James Herbie Difonzo Maurice A

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2004 In Praise of Statutes of Limitations in Sex Offense Cases James Herbie DiFonzo Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation James Herbie DiFonzo, In Praise of Statutes of Limitations in Sex Offense Cases, 41 Hous. L. Rev. 1205 (2004) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/461 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE IN PRAISE OF STATUTES OF LIMITATIONS IN SEX OFFENSE CASES James Herbie DiFonzo* "Rapists Shouldn't Be Able to Run Out the Clock."' "'[DNA] is very, very reliable if you do two things right: if you test it right, and if you interpret the results right .... The problem is that jurors think it's absolute and infallible.'"2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1206 II. ARE STATUTES OF LIMITATIONS STILL RELEVANT IN THE AGE OF DNA? .......................................................... 1209 A. Limitations Policy Revisited ....................................... 1209 B. The Impact of DNA Technology on Limitations Policy in Sexual Offense Cases ................................... 1217 C. Indicting "JohnDoe, Unknown Male with Matching Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) Profile"........ 1226 * Professor of Law, Hofstra University School of Law. J.D., M.A., 1977, Ph.D., 1993, University of Virginia. E-mail: [email protected].