The General Articles, Articles 133 and 134 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moves to Amend HF No. 752 As Follows: Delete Everything After the Enacting Clause and Insert

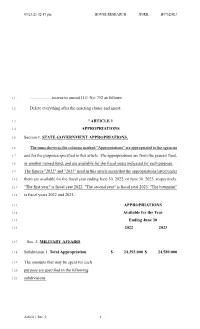

03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 752 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. STATE GOVERNMENT APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the columns marked "Appropriations" are appropriated to the agencies 1.7 and for the purposes specified in this article. The appropriations are from the general fund, 1.8 or another named fund, and are available for the fiscal years indicated for each purpose. 1.9 The figures "2022" and "2023" used in this article mean that the appropriations listed under 1.10 them are available for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2022, or June 30, 2023, respectively. 1.11 "The first year" is fiscal year 2022. "The second year" is fiscal year 2023. "The biennium" 1.12 is fiscal years 2022 and 2023. 1.13 APPROPRIATIONS 1.14 Available for the Year 1.15 Ending June 30 1.16 2022 2023 1.17 Sec. 2. MILITARY AFFAIRS 1.18 Subdivision 1. Total Appropriation $ 24,393,000 $ 24,589,000 1.19 The amounts that may be spent for each 1.20 purpose are specified in the following 1.21 subdivisions. Article 1 Sec. 2. 1 03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 2.1 Subd. 2. Maintenance of Training Facilities 9,772,000 9,772,000 2.2 Subd. 3. General Support 3,507,000 3,633,000 2.3 Subd. 4. Enlistment Incentives 11,114,000 11,114,000 2.4 The appropriations in this subdivision are 2.5 available until June 30, 2025, except that any 2.6 unspent amounts allocated to a program 2.7 otherwise supported by this appropriation are 2.8 canceled to the general fund upon receipt of 2.9 federal funds in the same amount to support 2.10 administration of that program. 2.11 If the amount for fiscal year 2022 is 2.12 insufficient, the amount for 2023 is available 2.13 in fiscal year 2022. -

Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?

Nebraska Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Article 8 1955 Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness? James W. Hewitt University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation James W. Hewitt, Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?, 34 Neb. L. Rev. 518 (1954) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol34/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 518 NEBRASKA LAW REVIEW CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-UNIFORM CODE OF MILITARY JUSTICE-GENERAL ARTICLE VOID FOR VAGUENESS.? Much has been said or written about the rights of servicemen under the new Uniform Code of Military Justice,1 which is the source of American written military law. Some of the major criticisms of military law have been that it is too harsh, too vague, and too careless of the right to due process of law. A large por tion of this criticism has been leveled at Article 134,2 the general, catch-all article of the Code. Article 134 provides: 3~ Alabama. Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, l\Iaine, l\Iaryland, l\Iasschusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Vermont. South Carolina has the privilege by case decision. See note 4 supra. 1 64 Stat. 107 <1950l, 50 U.S.C. §§ 551-736 (1952). -

STACY LEA BAKER, ) Case No. 10-90127-BHL-7 ) Debtor

Case 10-59029 Doc 59 Filed 09/28/11 EOD 09/29/11 08:04:30 Pg 1 of 20 SO ORDERED: September 28, 2011. ______________________________ Basil H. Lorch III United States Bankruptcy Judge UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA NEW ALBANY DIVISION In re: ) ) STACY LEA BAKER, ) Case No. 10-90127-BHL-7 ) Debtor. ) ) ) MURPHY OIL USA, INC., ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Adv. No. 09-59029 ) STACY LEA BAKER, ) ) Defendant. ) JUDGMENT This matter is before the Court on the Plaintiff’s Complaint to Determine Liability and Non-Dischargability of Debt Under 11 U.S.C. § 523, as supplemented by its More Definite Case 10-59029 Doc 59 Filed 09/28/11 EOD 09/29/11 08:04:30 Pg 2 of 20 Statement of the Claim [Docket # 41].1 The Court tried the matter on June 1, 2011. The Plaintiff and Defendants submitted post-trial briefs [Docket #s 71 and 72, respectively] on June 17, 2011. Murphy Oil USA, Inc. (“Murphy”), the Plaintiff, seeks a determination that the Defendants, John M. Baker and Stacy Lea Baker, are liable to it under various state law theories. Further, Murphy seeks a judgment liquidating the Bakers’ alleged obligations to Murphy and finding that the debts are excepted from discharge in their respective Chapter 7 bankruptcy cases pursuant to 11 U.S.C. § 523(a)(2), (4), or (6). Having considered the foregoing, and for the reasons set forth below, the Court finds Mr. Baker to be liable to Murphy in the amount of $691,757.78, which judgment may not be discharged in Mr. -

Gentlemen Under Fire: the U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 1 June 2008 Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming Elizabeth L. Hillman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Elizabeth L. Hillman, Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming, 26(1) LAW & INEQ. 1 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol26/iss1/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Gentlemen Under Fire: The U.S. Military and "Conduct Unbecoming" Elizabeth L. Hillmant Introduction ..................................................................................1 I. Creating an Officer Class ..................................................10 A. "A Scandalous and Infamous" Manner ...................... 11 B. The "Military Art" and American Gentility .............. 12 C. Continental Army Prosecutions .................................15 II. Building a Profession .........................................................17 A. Colonel Winthrop's Definition ...................................18 B. "A Stable Fraternity" ................................................. 19 C. Old Army Prosecutions ..............................................25 III. Defending a Standing Army ..............................................27 A. "As a Court-Martial May Direct". ............................. 27 B. Democratization and its Discontents ........................ 33 C. Cold War Prosecutions ..............................................36 -

GOOD ORDER and DISCIPLINE Second Quarter, Fiscal Year 2019 This Publishes to the Coast Guard Community a Summary of Disciplinary

GOOD ORDER AND DISCIPLINE Second Quarter, Fiscal Year 2019 This publishes to the Coast Guard community a summary of disciplinary and administrative actions taken when Coast Guard military members or civilian employees failed to uphold the high ethical, moral, and professional standards we share as members of the Coast Guard. Even though the military and civilian systems are separate, with different procedures, rights, and purposes, the underlying values remain the same. Actions from both systems are included to inform the Coast Guard community of administrative and criminal enforcement actions. The following brief descriptions of offenses committed and punishments awarded are the result of Coast Guard general, special, and summary courts-martial and selected military and civilian disciplinary actions taken service-wide during the second quarter of Fiscal Year 2019. General and special courts-martial findings of guilt are federal criminal convictions; other disciplinary actions are non-judicial or administrative in nature. When appropriate, actions taken as a result of civil rights complaints are also described. Details of the circumstances surrounding most actions are limited to keep this summary to a manageable size and to protect victim privacy. Direct comparison of cases should not be made because there are many variables involved in arriving at the resulting action. The circumstances surrounding each case are different, and disciplinary or remedial action taken is dependent upon the particular facts and varying degrees of extenuation and mitigation. In many cases, further separation or other administrative action may be pending. Note: A court-martial sentence may be accompanied by other administrative action. A case falling under more than one of the categories below has been listed only once and placed under the category considered most severe in its consequences unless otherwise noted. -

Volume 4 Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2015

TM VOLUME 4 ISSUE 1 FALL/WINTER 2015 National Security Law Journal George Mason University School of Law 3301 Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22201 www.nslj.org © 2015 National Security Law Journal. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Publication Data (Serial) National Security Law Journal. Arlington, Va. : National Security Law Journal, 2013- K14 .N18 ISSN: 2373-8464 Variant title: NSLJ National security—Law and legislation—Periodicals LC control no. 2014202997 (http://lccn.loc.gov/2014202997) Past issues available in print at the Law Library Reading Room of the Library of Congress (Madison, LM201). VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 (FALL/WINTER 2015) ISBN-13: 978-1523203987 ISBN-10: 1523203986 ARTICLES PLANNING FOR CHANGE: BUILDING A FRAMEWORK TO PREDICT FUTURE CHANGES TO THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT Patrick Walsh QUANTUM LAWMAKING: HOW NATIONAL SECURITY LAW HAPPENS WHEN WE’RE NOT LOOKING Jesse Medlong COMMENTS TERROR IN MEXICO: WHY DESIGNATING MEXICAN CARTELS AS TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS EASES PROSECUTION OF DRUG TRAFFICKERS UNDER THE NARCOTERRORISM STATUTE Stephen R. Jackson CYBERSPACE: THE 21ST-CENTURY BATTLEFIELD EXPOSING SOLDIERS, SAILORS, AIRMEN, AND MARINES TO POTENTIAL CIVIL LIABILITIES Molly Picard VOLUME 4 FALL/WINTER 2015 ISSUE 1 PUBLISHED BY GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW Cite as 4 NAT’L SEC. L.J. ___ (2015). The National Security Law Journal (“NSLJ”) is a student-edited legal periodical published twice annually at George Mason University School of Law in Arlington, Virginia. We print timely, insightful scholarship on pressing matters that further the dynamic field of national security law, including topics relating to foreign affairs, homeland security, intelligence, and national defense. Visit our website at www.nslj.org to read our issues online, purchase the print edition, submit an article, learn about our upcoming events, or sign up for our e-mail newsletter. -

October 1988 Federal Sentencing Guidelines Manual

UNITED STATES SENTENCING COMMISSION GUIDEUNES MANUAL [Incorporating guideline amendments effective October 15, 1988] UNITED STATES SENTENCING COMMISSION 1331 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE, NW SUITE 14OO WASHINGTON, D.C. 20004 (202) 662-8800 William W. Wilklns, Jr. Chairman Michael K. Block Stephen G. Breyer Helen G. Corrothers George E. MacKinnon llene H. Nagel Benjamin F. Baer (ex officio) Ronald L. Gainer (ex officio) William W. Wilkins, Jr. Chairman Michael K. Block Stephen G. Breyer Helen G. Corrothers George E. MacKinnon llene H. Nagel Benjamin F. Baer (ex-officio) Ronald L. Gainer (ex-officio) Note: This document contains the text of the Guidelines Manual incorporating amendments effective January 15, 1988, June 15, 1988, and October 15, 1988. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: Introduction and General Principles. Part A - Introduction 1.1 1. Authority 1.1 2. The Statutory Mission_ 1.1 3. The Basic Approach 1.2 4. The Guidelines' Resolution of Major Issues 1.5 5. A Concluding Note 1.12 Part B - General Application Principles 1.13 CHAPTER TWO: Offense Conduct 2.1 Part A - Offenses Against the Person 2.3 1. Homicide 2.3 2. Assault 2.4 3. Criminal Sexual Abuse 2.8 4. Kidnapping, Abduction, or Unlawful Restraint 2.11 5. Air Piracy 2.12 6. Threatening Communications 2.13 Part B - Offenses Involving Property 2.15 1. Theft, Embezzlement, Receipt of Stolen Property, and Property Destruction 2.15 2. Burglary and Trespass 2.19 3. Robbery, Extortion, and Blackmail 2.21 4. Commercial Bribery and Kickbacks 2.25 5. Counterfeiting, Forgery, and Infringement of Copyright or Trademark 2.27 6. -

Pub. L. 108–136, Div. A, Title V, §509(A)

§ 777a TITLE 10—ARMED FORCES Page 384 Oct. 5, 1999, 113 Stat. 590; Pub. L. 108–136, div. A, for a period of up to 14 days before assuming the title V, § 509(a), Nov. 24, 2003, 117 Stat. 1458; Pub. duties of a position for which the higher grade is L. 108–375, div. A, title V, § 503, Oct. 28, 2004, 118 authorized. An officer who is so authorized to Stat. 1875; Pub. L. 109–163, div. A, title V, wear the insignia of a higher grade is said to be §§ 503(c), 504, Jan. 6, 2006, 119 Stat. 3226; Pub. L. ‘‘frocked’’ to that grade. 111–383, div. A, title V, § 505(b), Jan. 7, 2011, 124 (b) RESTRICTIONS.—An officer may not be au- Stat. 4210.) thorized to wear the insignia for a grade as de- scribed in subsection (a) unless— AMENDMENTS (1) the Senate has given its advice and con- 2011—Subsec. (b)(3)(B). Pub. L. 111–383 struck out sent to the appointment of the officer to that ‘‘and a period of 30 days has elapsed after the date of grade; the notification’’ after ‘‘grade’’. 2006—Subsec. (a). Pub. L. 109–163, § 503(c), inserted ‘‘in (2) the officer has received orders to serve in a grade below the grade of major general or, in the case a position outside the military department of of the Navy, rear admiral,’’ after ‘‘An officer’’ in first that officer for which that grade is authorized; sentence. (3) the Secretary of Defense (or a civilian of- Subsec. (d)(1). -

Military Courts and Article III

Military Courts and Article III STEPHEN I. VLADECK* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................... 934 I. MILITARY JUSTICE AND ARTICLE III: ORIGINS AND CASE LAW ...... 939 A. A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO U.S. MILITARY COURTS ........... 941 1. Courts-Martial ............................... 941 2. Military Commissions ......................... 945 B. THE NORMATIVE JUSTIFICATIONS FOR MILITARY JUSTICE ....... 948 C. THE SUPREME COURT’S CONSTITUTIONAL DEFENSE OF COURTS-MARTIAL ................................. 951 D. THE SUPREME COURT’S CONSTITUTIONAL DEFENSE OF MILITARY COMMISSIONS .................................... 957 II. RECENT EXPANSIONS TO MILITARY JURISDICTION ............... 961 A. SOLORIO AND THE SERVICE-CONNECTION TEST .............. 962 B. ALI AND CHIEF JUDGE BAKER’S BLURRING OF SOLORIO’S BRIGHT LINE .......................................... 963 C. THE MCA AND THE “U.S. COMMON LAW OF WAR” ............ 965 D. ARTICLE III AND THE CIVILIANIZATION OF MILITARY JURISDICTION .................................... 966 E. RECONCILING THE MILITARY EXCEPTION WITH CIVILIANIZATION .................................. 968 * Professor of Law, American University Washington College of Law. © 2015, Stephen I. Vladeck. For helpful discussions and feedback, I owe deep thanks to Zack Clopton, Jen Daskal, Mike Dorf, Gene Fidell, Barry Friedman, Amanda Frost, Dave Glazier, David Golove, Tara Leigh Grove, Ed Hartnett, Harold Koh, Marty Lederman, Peter Margulies, Jim Pfander, Zach Price, Judith Resnik, Gabor Rona, Carlos Va´zquez, Adam Zimmerman, students in my Fall 2013 seminar on military courts, participants in the Hauser Globalization Colloquium at NYU and Northwestern’s Public Law Colloquium, and colleagues in faculty workshops at Cardozo, Cornell, DePaul, FIU, Hastings, Loyola, Rutgers-Camden, and Stanford. Thanks also to Cynthia Anderson, Gabe Auteri, Gal Bruck, Caitlin Marchand, and Pasha Sternberg for research assistance; and to Dean Claudio Grossman for his generous and unstinting support of this project. -

Self-Help in the Collection of Debts As a Defense to Criminal Prosecution

Washington University Law Review Volume 24 Issue 1 1938 Self-Help in the Collection of Debts as a Defense to Criminal Prosecution Milton H. Aronson Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Milton H. Aronson, Self-Help in the Collection of Debts as a Defense to Criminal Prosecution, 24 WASH. U. L. Q. 117 (1938). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol24/iss1/11 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19381 NOTES SELF-HELP IN THE COLLECTION OF DEBTS AS A DEFENSE TO CRIMINAL PROSECUTION Adverse economic conditions present the spectacle of petty creditors going to unusual lengths to collect. Some apply cajol- ery, trickery, threats, even force in attempting to secure pay- ments. But save in instances of self-defense, recaption and repri- sals, entry on lands, the abatement of nuisances, and distraint, the right to self-redress is not recognized,' because The public peace is a superior consideration to any one man's private property; and * * * , if individuals were once allowed to use private force as a remedy for private injuries, all social justice must cease, the strong would give law to the weak, and every man would revert to a state of nature; for these reasons it is provided that this natural right * * * shall never be exercised where such exertion must occasion strife and bodily contention, or endanger the peace of so- 2 ciety. -

Infanticide in Early Modem Gennany: the Experience of Augsburg, Memmingen, Ulm, and Niirdlingen, 1500-1800

Infanticide in Early Modem Gennany: the experience of Augsburg, Memmingen, Ulm, and Niirdlingen, 1500-1800 Margaret Brannan Lewis Charlottesville, Virginia M.A., History, University of Virginia, 2008 B.A., History and Gennan, Furman University, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia May, 2012 i Abstract Between 1500 and 1800, over 100 women and men were arrested for infanticide or abortion in the city of Augsburg in southern Germany. At least 100 more were arrested for the same crime in the three smaller cities of Ulm, Memmingen, and Nördlingen. Faced with harsh punishments as well as social stigma if found pregnant out of wedlock, many women in early modern Europe often saw abortion or infanticide as their only option. At the same time, town councils in these southern German cities increasingly considered it their responsibility to stop this threat to the godly community and to prosecute cases of infanticide or abortion and to punish (with death) those responsible. The story of young, unmarried serving maids committing infanticide to hide their shame is well-known, but does not fully encompass the entirety of how infanticide was perceived in the early modern world. This work argues that these cases must be understood in a larger cultural context in which violence toward children was a prevalent anxiety, apparent in popular printed literature and educated legal, medical, and religious discourse alike. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this anxiety was expressed in and reinforced by woodcuts featuring mass murders of families, deformed babies, and cannibalism of infants by witches and other dark creatures. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. __________ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States LAWRENCE G. HUTCHINS III, SERGEANT, UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI S. BABU KAZA CHRIS G. OPRISON LtCol, USMCR DLA Piper LLP (US) THOMAS R. FRICTON 500 8th St, NW Captain, USMC Washington DC Counsel of Record Civilian Counsel for U.S. Navy-Marine Corps Petitioner Appellate Defense Division 202-664-6543 1254 Charles Morris St, SE Washington Navy Yard, D.C. 20374 202-685-7291 [email protected] i QUESTION PRESENTED In Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970), this Court held that the collateral estoppel aspect of the Double Jeopardy Clause bars a prosecution that depends on a fact necessarily decided in the defendant’s favor by an earlier acquittal. Here, the Petitioner, Sergeant Hutchins, successfully fought war crime charges at his first trial which alleged that he had conspired with his subordinate Marines to commit a killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim. The members panel (jury) specifically found Sergeant Hutchins not guilty of that aspect of the conspiracy charge, and of the corresponding overt acts and substantive offenses. The panel instead found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the lesser-included offense of conspiring to commit an unlawful killing of a named suspected insurgent leader, and found Sergeant Hutchins guilty of the substantive crimes in furtherance of that specific conspiracy. After those convictions were later reversed, Sergeant Hutchins was taken to a second trial in 2015 where the Government once again alleged that the charged conspiracy agreement was for the killing of a randomly selected Iraqi victim, and presented evidence of the overt acts and criminal offenses for which Sergeant Hutchins had previously been acquitted.