Bridesourcing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expectant Urbanism Time, Space and Rhythm in A

EXPECTANT URBANISM TIME, SPACE AND RHYTHM IN A SMALLER SOUTH INDIAN CITY by Ian M. Cook Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors: Professor Daniel Monterescu CEU eTD Collection Professor Vlad Naumescu Budapest, Hungary 2015 Statement I hereby state that the thesis contains no material accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Budapest, November, 2015 CEU eTD Collection Abstract Even more intense than India's ongoing urbanisation is the expectancy surrounding it. Freed from exploitative colonial rule and failed 'socialist' development, it is loudly proclaimed that India is having an 'urban awakening' that coincides with its 'unbound' and 'shining' 'arrival to the global stage'. This expectancy is keenly felt in Mangaluru (formerly Mangalore) – a city of around half a million people in coastal south Karnataka – a city framed as small, but with metropolitan ambitions. This dissertation analyses how Mangaluru's culture of expectancy structures and destructures everyday urban life. Starting from a movement and experience based understanding of the urban, and drawing on 18 months ethnographic research amongst housing brokers, moving street vendors and auto rickshaw drivers, the dissertation interrogates the interplay between the city's regularities and irregularities through the analytical lens of rhythm. Expectancy not only engenders violent land grabs, slum clearances and the creation of exclusive residential enclaves, but also myriad individual and collective aspirations in, with, and through the city – future wants for which people engage in often hard routinised labour in the present. -

A Discourse on the Deconstruction of Spirit Worship of Tulunadu

A Peer-Reviewed Refereed e-Journal Legend of Koragajja: A Discourse on the Deconstruction of Spirit Worship of Tulunadu Mridul C Mrinal MA in English and Comparative Literature Central University of Kerala, Kasaragod. The Social stratification in a community is often complex and ambiguous in nature. Upon the rise of each nation states and civilization, there were several parameters, which determined the social stratification. In ancient Greece, the word used to denote the divisions are genos. The ancient Greek society was divided into citizens, metics and slaves. In ancient Rome, the social stratification was identified with mainly two groups, Patricians and Plebeians. The chief resource for the social stratification parameters are economical in nature. Other factors such as tradition and beliefs are often can be said to have rooted in the wider economic subject. The term class is often associated with economics. There are usually hegemonial and subdued elements in social stratifications. In ancient Greece, the hegemonial element is found associated with the citizens, who are free and members of the assembly whereas slaves were the subdued element who were brought into slavery. In ancient Rome, the hegemonial element were the patricians whereas the plebeians were the subdued. These ideas can often be observed with Class struggle and historical materialism. The division of history into stages based on the relation of the classes is an important aspect of Historical materialism. In India, the main social stratification parameter is the caste.it could be claimed as ceremonial as well as economic in nature. BR Ambedkar observes Endogamy as a product of ceremonial caste. -

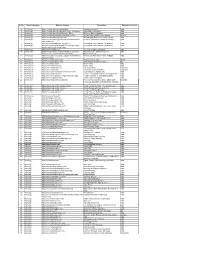

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization Indus Valley Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 4 Archaelogy http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Post/881715 Ancient Vishnu Idol Found in Russia Russia 5 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/ Archeological Evidence of Vedic System India 6 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/scientific- Scientific Verification of Vedic Knowledge India verif-vedas.html 7 Archaelogy http://www.ariseindiaforum.org/?p=457 Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India 8 Archaelogy http://www.dwarkapath.blogspot.com/2010/12/why- Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India dwarka-submerged-in-water.html 9 Archaelogy http://www.harappa.com/ The Ancient Indus Civilization India 10 Archaelogy http://www.puratattva.in/2010/10/20/mahendravadi- Mahendravadi – Vishnu Temple of India vishnu-temvishnu templeple-of-mahendravarman-34.html of mahendravarman 34.html Mahendravarman 11 Archaelogy http://www.satyameva-jayate.org/2011/10/07/krishna- Krishna and Rath Yatra in Ancient Egypt India rathyatra-egypt/ 12 Archaelogy http://www.vedicempire.com/ Ancient Vedic heritage World 13 Architecture http://www.anishkapoor.com/ Anish Kapoor Architect London UK 14 Architecture http://www.ellora.ind.in/ Ellora Caves India 15 Architecture http://www.elloracaves.org/ Ellora Caves India 16 Architecture http://www.inbalistone.com/ Bali Stone Work Indonesia 17 Architecture http://www.nuarta.com/ The Artist - Nyoman Nuarta Indonesia 18 Architecture http://www.oocities.org/athens/2583/tht31.html Build temples in Agamic way India 19 Architecture http://www.sompuraa.com/ Hitesh H Sompuraa Architects & Sompura Art India 20 Architecture http://www.ssvt.org/about/TempleAchitecture.asp Temple Architect -V. -

Handicraft Survey Monographs, Part VII-B, Vol-XI

PRG. 175 B(N) 750 CENSUS OF INDIA, 1961 VOLUME XI MY§ORE PART VII-B HANDICRAFT SURVEY MONOGRAPHS Editor K. BALASUBRAMANYAM of the Indian Administrative Service, Superintendent of Census Operations in JJlYMre [976 For ordinary edition Price: Inland Rs. 12-0'1 or Foreign £. 1.40 or $ 4.32 For deluxe edition Price: lnlanll Rs. 23.0() or Fureign £. 2.68 or $ 8.28 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XI-MYSORE List of Central Government Publications Part I-A General Report Part I-B Report on Vital Statistics Part I-e Subsidiary Tables Part II-A General Population Tables Part II-B(i) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) Part II-B(ii) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-1 X) Part II-C Cultural and Migration Tables Part III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVlI) Part IV-A Report on Housing and Establishment Part IV-B Housing and Establishments Tables Part V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part VI Village Survey Monographs Part VII Handicraft Survey Monographs Part VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration ) f- not for sale Part V III-B Administration Report-Tabulation ) State Government Publications ] 9 DISTRICT CENSUS HAND BO OKS MYSORE STATE SURVEY OF SELECTE;D HANDICRAFTS, 1961 SCALE 2" 4B 72 ""I.ES q=~!~~; i ; [ ~!i!B; l 20 40 60 80 100 lNQEX TO NUMBERS (!) 8,ORJ, WARE (D POTTERY MAHARASHTRA STATE ~ CARPt;TS Of' NA\W.GuN,p (j) SILK WEAVING AT ICOLLEGJoI. -

Village Survey Monographs, Kaginelli Village, No-16, Part VI, Vol-XI

PRO. 174. 31 (N) 1,000 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XI MYSORE PART VI VILLAGE SURVEY MONOGRAPHS No. 16, KAGINELLI VILLAGE Byadgi TaIuk, Dharwar District Editor: K. BALASUBRAMANYAM, of the Indian Administrative Service, Superintendent of Census Operations in Mysorc. 1970 PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE MANIPAL POWER PRESS. MANIPAL (SOUTH KANARA) AND PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DBLH(.6 Price: Inland Rs. 3.15 or Foreign 7 sh. 5 d. or 1 S 14 Cents. 7 . 7 • -. 17' 13' istrict J./~GcI·QuRrtus a/uk " illig'~ S~}ected tate boundary ., 7 S· VILLAGE SURVEY REPORT ON KAGINELLI Field Investigation, Tabulation and Draft Report Sri M. S. Ramachandra, B.SC. Invej tigator. Supervision and Guidance Sri K. L. Suryanaraynan, B.A.,B.L. Deputy Superintendent of Census Operations in Mysore (Socio-Economic Survey) Final Report Sri C. M. Chandawarkar. B.SC. DepulY Superintendent of Census Operations in Mysore, (District Hand Books) Bang%re Photographs Sri S. Ramachandra. B.SC. Senior Technical Assistant FOREWORD Apart from laying the foundations of demography (a) At least eight villages were to be so selected in this subcontinent, a hundred years of the Indian that each of them would contain one dominant Census has also produced 'elaborate and scholarly community with one predominating occu accounts of the variegated phenomena of Indian life pation, e.g. fishermen, forest workers, jhum sometimes with no statistics attached, but usually cultivators, potters, weavers, salt-makers, quarry with just enough statistics to give empirical under workers, etc. A village should have a mini pinning to their conclusions.' In a country, largely mum population of 400, the optimum being illiterate, where statistical or numerical comprehen between 500 and 700. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. No. Reference Broad catergory Website Address Description Country 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/m Hindu Kush odern/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temp Hindu Temples of Kabul les_of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?modul Hindu Temples of Afaganistan e=pluspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint &title=Hindu%20Temples%20in%20Afg hanistan%20.html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

Citizenship Experiences of the Goan Catholics

School of Social Sciences and Humanities Citizenship Experiences of the Goan Catholics Jason Keith Fernandes A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Anthropology Supervisor: Professor Rosa Maria de Figueiredo Perez, Professora Associada com Agregação, ISCTE-University Institute of Lisbon June 2013 School of Social Sciences and Humanities Citizenship Experiences of the Goan Catholics Jason Keith Fernandes A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Anthropology Jury Doutora Maria Paula Gutierres Meneses Investigadora do Centro de Estudos Sociais da Universidade de Coimbra Doutora Pamila Gupta Senior Researcher the University of Witwatersrand Doutor Everton Vasconcelos Machado Investigador de Pós-Doutoramento do Centro de Estudos Comparatistas da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa Doutor Miguel de Matos Castanheira do Vale de Almeida, Professor Associado com Agregação do Departamento de Antropologia da ECSHumanas do ISCTE-IUL Doutora Rosa Maria Figueiredo Perez Professora Associada com Agregação do Departamento de Antropologia da ECSHumanas do ISCTE-IUL (Supervisor) Research project supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia June 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that the nature of the citizenship experience of the Catholics in the Indian state of Goa is the experience of those located between civil society and political society. This argument commences from the postulate that the recognition of Konkani in the Devanagari script as the official language of Goa, determined the boundaries of the state’s civil society.Through an ethnographic study of the contestations around the demand that the Roman script also be officially recognised, the thesis demonstrates how by deliberately excluding the Roman script for the language, the largely lower-caste and lower-class Catholic users of the script were denoted as less than authentic members of the legitimate civil society of the state. -

Village Survey Monographs, Naravi Village, No-3, Part VI, Vol-XI

PRG. 174.3 (N) 1000 CENSUS OF IN D I A, 196 1 VOLUME XI MYSORE PART VI VILLAGE SURVEY MONOGRAPHS No. 3 NARAVI VILLAGE BELTHANGADY TALUK, SOUTH KANARA DISTRICT Editor K. BALASUBRAMANYAM of the Indian Adminisfrative Sen'ice, Superintendent of Census Operations, Mysore PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE MANAGER GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS COfMBATORE AND PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUIlLICATIONS DELm-6 1965 7 . 7 • MAP OF MYSORE MILES ....1 17' 17' 16' 1S' ARABIAN SEA 13' tate boundary iltrice a/uK 7 S· Prepa,.ed by _K. V. LA)( MINARASIMHA VILLAGE SURVEY REPORT ON NARAVI FIELD INVESTIGATION AND FiRST DRAFT Sri C. A. Shivaramiah, M. A., Investigator. SUPERVIS[Ol", GUIDANCE AND FINAL DRAFT Sri K. L. Suryanarayanan, B. A., B. L., Deputy Superintendent oj Censlls Operarions (Specia{ Surreys), Mysore. TABUtATrON Sri r.,I. S. Rangaswamy, B. SC., Senior Technical Assist.7I1t. PHOTOGRAPHS Sri Dasappa, Photographer, Departmellf 0/ Ill/orlllatiol/ alld Publicity, Gorerl1illent oj Afysore, Banga/ore. Oi) FOREWORD Apart from laying the foundations of demography in this sub-continent, a hundred years of the Indian Census has also produced 'elaborate and scholarly accounts of the v~1riegated phenomena of Indian life-sometimes with no statistics attached, but usually with just enough statistics to give empirical underpinning to their conclusion'. In a country largely illiterate, where statistical or numerical comprehension of even such a simple thing as age was liable to be inaccurate, as understanding of the social structure was essential. It \vas more necessary to attain a broad under standing of what was happening around oneself than to wrap oneself up in 'statistical ingenuity' or 'mathematical manipulation'. -

He Made the Musiri Bani His Own Lakshmi Sreeram

COVER STORY T.K. GOVINDA RAO He made the Musiri bani his own Lakshmi Sreeram he teacher is seated on a generous collecting the surplus prasadam from the sofa. Students of various ages squat temple and selling it outside. “In those on the floor, singing in hush hush days, brahmins were treated very well. PRITEESH SHA PRITEESH Ttones. Everyone’s talam is soft. No one We were given two square meals a day dares to sing loudly, yet the slightest lapse everyday for free, if we had the poonal is noted by the teacher, who identifies the (sacred thread) on. And so it was possible culprit with unerring accuracy and makes to just be a loiterer, eat at the temple and a sharp remark. First the varnam – in 4 not do anything. But we also had to be speeds (vilamba kalam, tisram, madhyama up and about early in the morning. We kalam and tisram), then kriti after kriti brahmachari-s had to go into the temple in that particular raga, each followed by at 3.30 am and help around.” many rounds of kalpana swara – until the The normal course for any male child less stout-hearted among the students Sangita Kalanidhi T.K. Govinda Rao start crying in the heart. “Ayyo porum!” in his community to follow was to join The expression “bendu nimundidum!” comes again and the Maharaja College of Sanskrit in again to mind as the next round of swaraprastara starts. Tirupunitura after completing the third form in school, The class had begun at 11 am, and at 2.30 pm, the teacher, gather the title of Kavyabhooshanam after a four year 80 years old, is still raring to go, while the students have course in Sanskrit, and then join the service of a temple! started squirming and twisting and stretching their bodies. -

Tulu, a Grammar of (Bhatt).Pdf

Microfilmed by Univ. of Wis. Department of Photography 7 1 - 1 6 ,0 6 3 BHATT, Sooda Lakshminarayana, 1932- A GRAMMAR OF TULU (A DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGE) The University of Wisconsin, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, linguistics University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © Sooda Lakshminarayana Bhat-t-r 1Q71 All Rights Reserved (This title card prepared by The University of Wisconsin) PLEASE NOTE: The negative microfilm copy of this dissertation was prepared and inspected by the school granting the degree. We are using this film without further inspection or change. If there are any questions about the film content, please write directly to the school. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A GRAMMAR OP TTJLU (A DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGE) A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin in partial fulfillm ent of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. by j SOODA LAKSHMINARAYANA HIATT I Degree to be awarded January 1923- June 19— August 19— Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. To P ro fe s s o rs : Valdis. J. Zeps Dan. M. Matson John C. S treet This thesis having been approved in respect to form and mechanical execution is referred to you for judgment upon its substantial merit. (Q a >77- l S e r - J j Dean Approved as satisfying in substance the doctoral thesis requirement of the University of W isconsin. MaJ o r P ro f Date of Examination, Pec‘ ------------19—^ Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner.