Citizenship Experiences of the Goan Catholics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Social and Economic Development

Journal of Social and Economic Development Vol. 4 No.2 July-December 2002 Spatial Poverty Traps in Rural India: An Exploratory Analysis of the Nature of the Causes Time and Cost Overruns of the Power Projects in Kerala Economic and Environmental Status of Drinking Water Provision in Rural India The Politics of Minority Languages: Some Reflections on the Maithili Language Movement Primary Education and Language in Goa: Colonial Legacy and Post-Colonial Conflicts Inequality and Relative Poverty Book Reviews INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE BANGALORE JOURNAL OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT (Published biannually in January and July) Institute for Social and Economic Change Bangalore–560 072, India Editor: M. Govinda Rao Managing Editor: G. K. Karanth Associate Editor: Anil Mascarenhas Editorial Advisory Board Isher Judge Ahluwalia (Delhi) J. B. Opschoor (The Hague) Abdul Aziz (Bangalore) Narendar Pani (Bangalore) P. R. Brahmananda (Bangalore) B. Surendra Rao (Mangalore) Simon R. Charsley (Glasgow) V. M. Rao (Bangalore) Dipankar Gupta (Delhi) U. Sankar (Chennai) G. Haragopal (Hyderabad) A. S. Seetharamu (Bangalore) Yujiro Hayami (Tokyo) Gita Sen (Bangalore) James Manor (Brighton) K. K. Subrahmanian Joan Mencher (New York) (Thiruvananthapuram) M. R. Narayana (Bangalore) A. Vaidyanathan (Thiruvananthapuram) DTP: B. Akila Aims and Scope The Journal provides a forum for in-depth analysis of problems of social, economic, political, institutional, cultural and environmental transformation taking place in the world today, particularly in developing countries. It welcomes articles with rigorous reasoning, supported by proper documentation. Articles, including field-based ones, are expected to have a theoretical and/or historical perspective. The Journal would particularly encourage inter-disciplinary articles that are accessible to a wider group of social scientists and policy makers, in addition to articles specific to particular social sciences. -

Folk Theatre in Goa: a Critical Study of Select Forms Thesis

FOLK THEATRE IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SELECT FORMS THESIS Submitted to GOA UNIVERSITY For the Award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar Under the Guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K. J. Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. January 2018 CERTIFICATE As required under the University Ordinance, OA-19.8 (viii), I hereby certify that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, submitted by Ms. Tanvi Shridhar Kamat Bambolkar for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English has been completed under my guidance. The thesis is the record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to her by this or any other University. Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley Professor of English (Retd.), Goa University. Date: i DECLARATION As required under the University Ordinance OA-19.8 (v), I hereby declare that the thesis entitled, Folk Theatre in Goa: A Critical Study of Select Forms, is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Dr. (Mrs.) K.J.Budkuley, Professor of English (Retd.),Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in the thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or other similar titles to me, by this or any other University. Ms. -

Impact of Christian Missions an Overview

www.sosinclasses.com CHAPTER 4 IMPACT OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONS AN OVERVIEW 4.1 The Impact of missions, a summing up 4.2 Christian missions and English education CHAPTER FOUR IMPACT OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONS-AN OVERVIEW 4.1 The impact of missions, a summing up In the preceding part an attempt was made to understand the Christian missions in India in terms of western missionary expansion. As stated earlier, India had a hoary tradition of tolerance and assimilation. This tradition was the creation of the syncretic Hindu mind eager to be in touch with all other thought currents. “Let noble thoughts come to us from all sides”1 was the prayer of the Hindu sages. The early converts to Christianity lived cordially in the midst of Hindus respecting one another. This facilitated the growth of Christianity in the Indian soil perfectly as an Indian religion. The course of cordiality did not run smooth. The first shock to the cordial relation between Christian community and non-Christians was received from the famous Synod of Diamper. Latin rites and ordinances were imposed forcefully and a new world of Christendom was threatened to be extended without caring to understand the social peculiarities of the place where it was expected to grow and prosper and ignoring the religio-cultural sensitivity of the people amidst whom the 1 Rigveda 1-89-1. www.sosinclasses.com 92 new religion was to exist. As pointed out earlier the central thrust of the activities of the Jesuit missions established in India during the second half of sixteenth century was proselytizing the native population to Christianity. -

Indicative Pharmacy List for Oximeter

Licence Register Food & Drugs Administration Print Date : 31-Jul-2020 Sr/Firm No Firm Name , I.C / Manager Firm Address Issue Dt,Validity Cold Storage District / R.Pharmacist , Competent Person Dt,Renewal Dt, 24 Hr Open Firm Cons. Inspection Dt Lic App CIRCLE : Goa Head Office 1 om medical store chemist & druggist shop no. 305/1 franetta bldg, station road 23-Jan-2012 Yes 10081 mr. pradip p. naik curchorem goa 403706 22-Jan-2022 No SGO -D1301-annapurneshwari sherkhane Ph. 08322652835 Taluka :QUE 23-Jan-2017 AH PRO No C.P M. 9822155619 16-Feb-2017 2 ayushya medicentre chemist & druggist 2294,ground floor dr. buvaji family welfare 11-May-2007 Yes 10088 shaikh salim centre curchorem 403706 10-May-2022 No SGO -D78-mr.shaik salim Ph. Taluka :QUE 11-May-2017 AH PRO No C.P M. 9922769967 07-Jun-2017 3 kuntal medical stores chemist & druggist fgs-5 h.no.266 ground floor angelica arcade 11-Feb-2002 Yes 10091 mr. premanad phaldesai valetembi 403705 10-Feb-2022 No SGO -D1040-mr / phaldesai premanand krishan Ph. 08322664012 Taluka :QUE 11-Feb-2017 AH PRO No C.P M. 9823045316 12-Sep-2017 4 rohit chemist & druggist 4,h no 59 vaikunth bhavan,near petrol 14-Mar-2005 Yes 10092 mrs. nirmala r. naik pump quepem 403705 13-Mar-2025 No SGO -D746-naik ramdas pandhari Ph. 08322664441 Taluka :QUE 14-Mar-2020 AH PRO No C.P M. 9850469430 19-Jun-2018 5 maa medical store chemist & druggist shop no.1 j.k. chambers,near kadamba bus 18-May-1998 Yes 10103 mr. -

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the Study A) the Study Is Basically

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the study a) The study is basically a very good documentation of Goa's ancient and medieval period icons and sculptural remains. So far a wrong notion among many that Goa religio cultural past before the arrival of the Portuguese is intangible has been critically viewed and examined in this study. The research would help in throwing light on the pre-Portuguese era of the Goa's history. b) The craze of modernization and renovation of ancient and historic temples have made changes in the religio-cultural aspect of the society. Age old deities and concepts of worships have been replaced with new sculptures or icons. The new sculptures installed in places of the historic ones have been modified to the whims and fancies of many trustees or temple authorities thus changing the pattern of the religio-cultural past. While new icons substitute the old ones there are changes in attributes, styles and the historic features of the sculpture or image. Not just this but the old sculptures are immersed in water when the new one is being installed. Some customary rituals have been rapidly changed intentionally or unintentionally by the stake holders or the devotees. Moreover the most of the ancient rituals and customs associated with some icons have are in process of being stopped by the locals. Therefore a thorough documentation of these sculptures and antiquities with scientific attitude and research was the need of the hour. c) The iconographic details about many sculptures, worships or deities are scattered in many books and texts. -

October 2020

www.goajesuits.com Vol. 29, No. 10, October 2020 Grateful hearts and New Fire in the Vineyard In the midst of these difficult times, we celebrate the calling of five of our province men who will be ordained this year—Raul and Steven on 17 October at Milagres Church in Khanapur, and Lindsay, Menoy, and Nigel on 30 December at the Basilica of Bom Jesus in Old Goa. While we may not be able to be physically present for these ordinations (owing to govt. restrictions), I request all province members to set aside time to follow the ordinations online (or together on your community TV) and support our men with your prayers. Every now and then the Vineyard also needs New Fire—a fire that purifies and a fire that enkindles other fires. Soon you will have two new booklets in your hands—the Province Apostolic Plan 2020 and the Goa Province Policy for Protection of Minors and Vulnerable Adults from Sexual Abuse and Harassment (2020). The PAP document will provide us with a direction and yet, we are flexible, allowing the Holy Spirit to guide us at all times. The Protection Policy provides us with an opportunity to create safe, healthy, and happy environments for all those with whom we work. Despite the challenges of these times, many of our Jesuits worked hard to ensure that these two guiding documents were published so that we approach our mission with renewed enthusiasm. I encourage all to read them carefully, make your own notes in the margins, and use them well. -

The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010

– 1 – GOVERNMENT OF GOA The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010 – 2 – Edition: January 2017 Government of Goa Price Rs. 200.00 Published by the Finance Department, Finance (Debt) Management Division Secretariat, Porvorim. Printed by the Govt. Ptg. Press, Government of Goa, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Panaji-Goa – 403 001. Email : [email protected] Tel. No. : 91832 2426491 Fax : 91832 2436837 – 1 – Department of Town & Country Planning _____ Notification 21/1/TCP/10/Pt File/3256 Whereas the draft Regulations proposed to be made under sub-section (1) and (2) of section 4 of the Goa (Regulation of Land Development and Building Construction) Act, 2008 (Goa Act 6 of 2008) hereinafter referred to as “the said Act”, were pre-published as required by section 5 of the said Act, in the Official Gazette Series I, No. 20 dated 14-8- 2008 vide Notification No. 21/1/TCP/08/Pt. File/3015 dated 8-8-2008, inviting objections and suggestions from the public on the said draft Regulations, before the expiry of a period of 30 days from the date of publication of the said Notification in the said Act, so that the same could be taken into consideration at the time of finalization of the draft Regulations; And Whereas the Government appointed a Steering Committee as required by sub-section (1) of section 6 of the said Act; vide Notification No. 21/08/TCP/SC/3841 dated 15-10-2008, published in the Official Gazette, Series II No. 30 dated 23-10-2008; And Whereas the Steering Committee appointed a Sub-Committee as required by sub-section (2) of section 6 of the said Act on 14-10-2009; And Whereas vide Notification No. -

About Delhi: Delhi Is the Capital of India and Is the Home of the Administrative Center for the Country

Destinations Choice of Destinations: In our endeavor to offer the best possible solution to your medical needs, our team has explored the various destinations which offer benefits on any of the following parameters, needless to mention that the quality standards remain the same at all the selected locations. We offer a wide choice of destinations The selection of the places has been done on the basis of cost benefit in terms of affordability and availabity of accommodation, transport and environment for recuperation. Needless to mention, the standard of quality of treatment remains the same. About Delhi: Delhi is the Capital of India and is the home of the administrative center for the country. It also has a rich history that extends all the way back to the 6th century BC. Apart from its historical heritage the city is well known for all the historical sites worth visiting and the food. The city was born out of a complex past that defines the present state of its dynamism, beauty and ramifications. It is amazing to witness the coexistence of both the ancient and modern world in one city that showcases a diverse culture as well as traditional values and yet absorbing modern interventions making it worth exploring, be it the city in itself or the people enriched with variant characteristics. It is these diverse aspects that make Delhi what it is today and worth every bit of time that you spend scouting the by-lanes or the ancient monumental delights leaving you with a worthwhile acquaintance and memorable graffiti etched in your mind and heart forever. -

Official Gazette Government ·Of Go~ Daman and Diu

REGD. GOA 51 Panaji, 28th July, 1977 (Sravana 6, 1899) SERIES III No. 17 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT ·OF GO~ DAMAN AND DIU GOVERNMENT OF GOA•. DAMAN AND DIU Home Department (Transport and A~commodation) Directorate of Transport Public Notice I - Applications have been received for grant of renewal of stage carriage permits to operate on the following routes :_ Date ot Date ot Sr. No. receipt expiry Name and address of the applicant M. V.No. 1. 16·5·77 20·9·77 Mis. Amarante & Saude Transport, Cuncolim, Salcete~Goa. Margao to GDT 2299 Mapusa via Ponda, Sanquelim. Bicholim & back. (Renewal of GDPst/ 396/70). 2. 6·6·77 21·11·77 Shri Sebastiao PaIha, H; No. 321, St. Lourenco, Agasaim, Ilhas-Goa. GDT 2188 Agasalm toPanaji & back. (Renewal of GDPst/98/66). 3. 6·6·77 26·12·77 Shri Sivahari Rama Tiloji, Gudem, Siolim, Bardez-Goa. SioUm to Mapusa GDT 2017 & back. (Renewal of GDPst/136/66). 4. 9·6·77 16·10·77 8hri Kashinath Bablo Naik, H. No. 83, Post Porvorim, Bardez-Goa. Mapusa GDT 2270 to Panaji & back (Renewal of GDPst/346/70). 5. 9·6·77 16·10·77 Shri Kashinath Bablo Naik, H. No. 83, Post Porvorim, Bardez-Goa. Mapusa GDT 2147 to Panaji & back. (Renewal of GDPst/345/70). 6. 15·6·77 28·12·77 Shri Arjun F. Ven~rIenkar, Baradi, Velim, Salcete-Goa. Betul to Margao GDT 2103 via Velim. Assolna, Cuncolim, Chinchinim & back. (Renewal of GDPst/ /151/66). 7. 24-6·77 3·11·77 Janata Transport Company, Curtorim, Salcete--Goa. -

Coastal Property Resources in Goa – Alarming Trends

Coastal Property Resources in Goa – Alarming Trends Dr. Sairam Bhat Assistant Professor of Law, National Law School of India University, Bangalore and Ms. Smita Srivastava Sr. Lecturer, Saraswath College, Maupsa, Goa If you want a piece of Goa's coastline, follow three simple steps. Just grab the land, build on it(after making pretences that your structures are temporary) and then forget it. 1 Introduction Tourism in Goa has largely been and still remains ‘Beach tourism’. The beaches in Goa have been exploited to the hilt. Over 90% of domestic tourists and 99% of international tourists visit and reside along the beach front. 2 The packaging of Goa as a major international tourist destination is still actively underway, even though the number of tourists visiting Goa has exceeded the region’s carrying capacity, bringing about a steady and relentless degradation of the natural environment as well as a deterioration of the social and cultural fabric. Tourism, now is Goa’s Primary Industry. It handles 12% of all foreign tourist arrivals in India. Goa receives more tourists per annum than its total residential population (refer T.No.1, as per govt. sources, the population of Goa for the year 08-09 was 13.48 lakhs)3 The decisive issue facing any tourism destination is the benefit – cost ratio. This has never been calculated in the State. Destruction of the environment on the scale occurring in Goa can only be justified if the returns from any industry are such that they lead to enhancement of prosperity, provision of employment and reduction of poverty levels, since poverty is described as the greatest threat to environmental protection. -

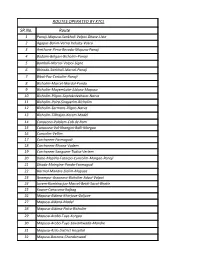

SR.No. Route ROUTES OPERATED by KTCL

ROUTES OPERATED BY KTCL SR.No. Route 1 Panaji-Mapusa-Sankhali-Valpoi-Dhave-Uste 2 Agapur-Borim-Verna Industy-Vasco 3 Amthane-Pirna-Revoda-Mapusa-Panaji 4 Badami-Belgavi-Bicholim-Panaji 5 Bamboli-Marcel-Valpoi-Signe 6 Bhiroda-Sankhali-Marcel-Panaji 7 Bibal-Paz-Cortalim-Panaji 8 Bicholim-Marcel-Mardol-Ponda 9 Bicholim-MayemLake-Aldona-Mapusa 10 Bicholim-Pilgao-Saptakoteshwar-Narva 11 Bicholim-Poira-Sinquerim-Bicholim 12 Bicholim-Sarmans-Pilgao-Narva 13 Bicholim-Tikhajan-Kerem-Madel 14 Canacona-Palolem-Cab de Ram 15 Canacona-Val-Khangini-Balli-Margao 16 Cuncolim-Vellim 17 Curchorem-Farmagudi 18 Curchorem-Rivona-Vadem 19 Curchorem-Sanguem-Tudva-Verlem 20 Dabe-Mopirla-Fatorpa-Cuncolim-Margao-Panaji 21 Dhada-Maingine-Ponda-Farmagudi 22 Harmal-Mandre-Siolim-Mapusa 23 Ibrampur-Assonora-Bicholim-Advoi-Valpoi 24 Juvem-Kumbharjua-Marcel-Betki-Savoi-Bhatle 25 Kawar-Canacona-Rajbag 26 Mapusa-Aldona-Khorjuve-Goljuve 27 Mapusa-Aldona-Madel 28 Mapusa-Aldona-Poira-Bicholim 29 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Korgao 30 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Sawantwada-Mandre 31 Mapusa-Azilo District Hospital 32 Mapusa-Bastora-Chandanwadi 33 Mapusa-Bicholim-Poira 34 Mapusa-Bicholim-Sankhali-Valpoi-Hivre 35 Mapusa-Calvi-Madel 36 Mapusa-Carona-Amadi 37 Mapusa-Colvale-Dadachiwadi-Madkai 38 Mapusa-Duler-Camurli 39 Mapusa-Karurli-Aldona-Pomburpa-Panaji 40 Mapusa-Khorjuve-Bicholim-Varpal 41 Mapusa-Marna-Siolim 42 Mapusa-Nachnola-Carona-Calvi 43 Mapusa-Palye-Succuro-Bitona-Panaji 44 Mapusa-Panaji-Fatorpha(Sunday) 45 Mapusa-Pedne-Pednekarwada-Mopa 46 Mapusa-Saligao-Calangute-Pilerne-Panaji 47 Mapusa-Siolim -

02/2018/SIC-I Shri Shivdas Harichandra Borkar, the Escrivao, Communidade of Cortalim Cortalim, Salcete- Goa

GOA STATE INFORMATION COMMISSION Kamat Tower, Seventh Floor, Patto Panaji-Goa --- -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Appeal No. 02/2018/SIC-I Shri Shivdas Harichandra Borkar, The Escrivao, Communidade of Cortalim Cortalim, Salcete- Goa. Pin Code: 403701 ………………Appellant. V/s. 1. Shri Tome Carvalho, R/o H.No.116 Nauta, Cortalim Goa Pin code 403701 2. The Public Information Officer Administrator of Communidade, South Zone, Margao- Goa. …….. Respondents Filed on: 5/1/2018 Decided on: 21/05/2018 AND Appeal No. 11/2018/SIC-I Shri Tome Carvalho, R/o H.No.116 Nauta, Cortalim ----------------------Appellant V/S 1. The Public Information Officer Administrator of Communidade, South Zone Margao- Goa. 2. The Escrivao, Communidade of Cortalim, Through the Administrator, Communidade of South Zone, Margao- Goa. --------------------------Respondents CORAM: Smt. Pratima K. Vernekar, State Information Commissioner Filed on: 15/1/2018 Decided on: 21/05/2018 1. As both the Appeal arising of common RTI application filed u/s 6(1) of Right To Information Act, 2005 and as the issue involved herein is identical , both the appeals are disposed by this common order. 1 2. The brief facts in above appeal No. 2 of 18 which is herein after referred to as first appeal are as under: a) Respondent No. 1 Shri Tome Carvelho by an application dated 25/05/2017 filed under section 6(1) of the RTI Act, sought for certified copies of the certain documents from Respondent No. 2 herein. Since Respondent No. 1 was not satisfied with the reply given by Respondent No. 2 he preferred 1st appeal before the FAA on 13/07/2017 wherein present appellant and Respondent No.