Nidān Vol. 4, No 2, December 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post Offices

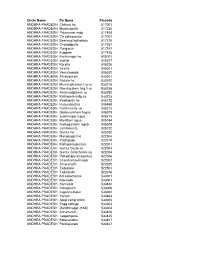

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Journal of Social and Economic Development

Journal of Social and Economic Development Vol. 4 No.2 July-December 2002 Spatial Poverty Traps in Rural India: An Exploratory Analysis of the Nature of the Causes Time and Cost Overruns of the Power Projects in Kerala Economic and Environmental Status of Drinking Water Provision in Rural India The Politics of Minority Languages: Some Reflections on the Maithili Language Movement Primary Education and Language in Goa: Colonial Legacy and Post-Colonial Conflicts Inequality and Relative Poverty Book Reviews INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE BANGALORE JOURNAL OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT (Published biannually in January and July) Institute for Social and Economic Change Bangalore–560 072, India Editor: M. Govinda Rao Managing Editor: G. K. Karanth Associate Editor: Anil Mascarenhas Editorial Advisory Board Isher Judge Ahluwalia (Delhi) J. B. Opschoor (The Hague) Abdul Aziz (Bangalore) Narendar Pani (Bangalore) P. R. Brahmananda (Bangalore) B. Surendra Rao (Mangalore) Simon R. Charsley (Glasgow) V. M. Rao (Bangalore) Dipankar Gupta (Delhi) U. Sankar (Chennai) G. Haragopal (Hyderabad) A. S. Seetharamu (Bangalore) Yujiro Hayami (Tokyo) Gita Sen (Bangalore) James Manor (Brighton) K. K. Subrahmanian Joan Mencher (New York) (Thiruvananthapuram) M. R. Narayana (Bangalore) A. Vaidyanathan (Thiruvananthapuram) DTP: B. Akila Aims and Scope The Journal provides a forum for in-depth analysis of problems of social, economic, political, institutional, cultural and environmental transformation taking place in the world today, particularly in developing countries. It welcomes articles with rigorous reasoning, supported by proper documentation. Articles, including field-based ones, are expected to have a theoretical and/or historical perspective. The Journal would particularly encourage inter-disciplinary articles that are accessible to a wider group of social scientists and policy makers, in addition to articles specific to particular social sciences. -

Directory 2017

DISTRICT DIRECTORY / PATHANAMTHITTA / 2017 INDEX Kerala RajBhavan……..........…………………………….7 Chief Minister & Ministers………………..........………7-9 Speaker &Deputy Speaker…………………….................9 M.P…………………………………………..............……….10 MLA……………………………………….....................10-11 District Panchayat………….........................................…11 Collectorate………………..........................................11-12 Devaswom Board…………….............................................12 Sabarimala………...............................................…......12-16 Agriculture………….....…...........................……….......16-17 Animal Husbandry……….......………………....................18 Audit……………………………………….............…..…….19 Banks (Commercial)……………..................………...19-21 Block Panchayat……………………………..........……….21 BSNL…………………………………………….........……..21 Civil Supplies……………………………...............……….22 Co-Operation…………………………………..............…..22 Courts………………………………….....................……….22 Culture………………………………........................………24 Dairy Development…………………………..........………24 Defence……………………………………….............…....24 Development Corporations………………………...……24 Drugs Control……………………………………..........…24 Economics&Statistics……………………....................….24 Education……………………………................………25-26 Electrical Inspectorate…………………………...........….26 Employment Exchange…………………………...............26 Excise…………………………………………….............….26 Fire&Rescue Services…………………………........……27 Fisheries………………………………………................….27 Food Safety………………………………............…………27 -

Pax Lumina – January 2021

Bimonthly Vol. 2 | No. 1 | January 2021 A Quest for Peace and Reconciliation The PLIGHT of SEXWORKERS & HUMAN TRAFFICKING There really can be no peace without justice. There can be no justice without truth. And there can be no truth, unless someone rises up to tell you the truth. - Louis Farrakhan A Quest for Peace and Reconciliation For E- Reading (Free Access) Those who would like to get print copy of www.paxlumina.com the magazine kindly email: [email protected] Vol. 2 | No. 1 | January 2021 A Quest for Peace and Reconciliation Advisory Board • Dr. Stanislaus D'Souza (President, Jesuit Conference of South Asia) • Dr. E.P. Mathew (Kerala Jesuit Provincial) • Dr. Ted Peters (CTNS, Berkeley, USA) • Dr. Carlos E. Vasco (Former Professor, National University of Colombia) • Dr. Thomas Cattoi (JST-SCU, California) • Dr. Kifle Wansamo Editor (Hekima Institute of Peace Studies, Nairobi) • Dr. Jacob Thomas IAS (Retd.) • Justice Kurian Joseph (Former Judge, Supreme Court of India) Managing Editor • Dr. George Pattery (Former Professor, • Dr. Binoy Pichalakkattu Visva-Bharati University, West Bengal) Associate Editor • Dr. K. Babu Joseph (Former Vice Chancellor, CUSAT, Kochi) • Dr. K.M. Mathew • Dr. Ms. Sonajharia Minz (Vice Chancellor, Sido Kanhu Murmu Contributing Editors University, Jharkhand) • Dr. Augustine Pamplany • Dr. Jancy James (Former Vice Chancellor, Central University of Kerala) • Dr. Francis Gonsalves • Dr. Kuruvilla Pandikattu • Dr. C. Radhakrishnan (Litteraeur, Kochi) • Roy Thottam • Dr. Denzil Fernandes (Director, Indian Social Institute, Delhi) • Dr. Neena Joseph • Dr. K.K. Jose • Devassy Paul (Former Principal, St. Thomas College, Pala) • Sheise Thomas • Dr. M. Arif (Adjunct Professor, • Sunny Jacob Premraj Sarda College, Ahamednagar) Design • Dr. -

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

Padma Vibhushan Padma Bhushan

Padma Vibhushan Name Field State/Country Public Affairs Bihar 1. George Fernandes (Posthumous) Public Affairs Delhi 2. Arun Jaitley (Posthumous) Sir Anerood Jugnauth Public Affairs Mauritius 3. M. C. Mary Kom Sports Manipur 4. Chhannulal Mishra Art Uttar Pradesh 5. Public Affairs Delhi 6. Sushma Swaraj (Posthumous) Others-Spiritualism Karnataka 7. Sri Vishveshateertha Swamiji Sri Pejavara Adhokhaja Matha Udupi (Posthumous) Padma Bhushan Name Field State/Country SN M. Mumtaz Ali (Sri M) Others-Spiritualism Kerala 8. Public Affairs Bangladesh 9. Syed Muazzem Ali (Posthumous) 10. Muzaffar Hussain Baig Public Affairs Jammu and Kashmir Ajoy Chakravorty Art West Bengal 11. Manoj Das Puducherry 12. Literature and Education Balkrishna Doshi Others-Architecture Gujarat 13. Krishnammal Jagannathan Social Work Tamil Nadu 14. S. C. Jamir Public Affairs Nagaland 15. Anil Prakash Joshi Social Work Uttarakhand 16. Dr. Tsering Landol Medicine Ladakh 17. Anand Mahindra Trade and Industry Maharashtra 18. Public Affairs Kerala 19. Neelakanta Ramakrishna Madhava Menon (Posthumous) Public Affairs Goa 20. Manohar Gopalkrishna Prabhu Parrikar (Posthumous) Prof. Jagdish Sheth USA 21. Literature and Education P. V. Sindhu Sports Telangana 22. Venu Srinivasan Trade and Industry Tamil Nadu 23. Padma Shri Name Field State/Country S.N. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Art Jharkhand 24. Dr. Yogi Aeron Medicine Uttarakhand 25. Jai Prakash Agarwal Trade and Industry Delhi 26. Jagdish Lal Ahuja Social Work Punjab 27. Kazi Masum Akhtar Literature and Education West Bengal 28. Ms. Gloria Arieira Literature and Education Brazil 29. Khan Zaheerkhan Bakhtiyarkhan Sports Maharashtra 30. Dr. Padmavathy Bandopadhyay Medicine Uttar Pradesh 31. Dr. Sushovan Banerjee Medicine West Bengal 32. Dr. Digambar Behera Medicine Chandigarh 33. -

Impact of Christian Missions an Overview

www.sosinclasses.com CHAPTER 4 IMPACT OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONS AN OVERVIEW 4.1 The Impact of missions, a summing up 4.2 Christian missions and English education CHAPTER FOUR IMPACT OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONS-AN OVERVIEW 4.1 The impact of missions, a summing up In the preceding part an attempt was made to understand the Christian missions in India in terms of western missionary expansion. As stated earlier, India had a hoary tradition of tolerance and assimilation. This tradition was the creation of the syncretic Hindu mind eager to be in touch with all other thought currents. “Let noble thoughts come to us from all sides”1 was the prayer of the Hindu sages. The early converts to Christianity lived cordially in the midst of Hindus respecting one another. This facilitated the growth of Christianity in the Indian soil perfectly as an Indian religion. The course of cordiality did not run smooth. The first shock to the cordial relation between Christian community and non-Christians was received from the famous Synod of Diamper. Latin rites and ordinances were imposed forcefully and a new world of Christendom was threatened to be extended without caring to understand the social peculiarities of the place where it was expected to grow and prosper and ignoring the religio-cultural sensitivity of the people amidst whom the 1 Rigveda 1-89-1. www.sosinclasses.com 92 new religion was to exist. As pointed out earlier the central thrust of the activities of the Jesuit missions established in India during the second half of sixteenth century was proselytizing the native population to Christianity. -

Current Affairs of January 2020 Quick Point

Studentsdisha.in Current Affairs of January 2020 Quick Point Content SI No. Topic Page Number 1 Important Day & Date with Theme 2-3 2 Important Appointments 3-5 3 Awards and Honours 5-21 Crossword Books Awards 7 Ramnath Goenka Excellence Awards 7-8 Pradhan Mantri Rashtriya Bal Puraskar 2020 8 National Bravery Award 2019 8-9 Padma Awards 2020 9-14 Jeevan Raksha Padak Award 2020 14-16 62nd Grammy Awards 2020 16-20 77th Golden Globe Award 2020 20-21 4 Sports 21-24 ICC Annual Award 2019 21-22 Australian Open 2020 22 5 BOOKS & Authors 24 6 Summit & Conference 24-25 7 Ranking and Index 25-26 8 MoU Between Countries 26 9 OBITUARIES 26-27 10 National & International News 28-35 1 Studentsdisha.in January 2020 Quick Point Important Day & Date with Theme of January 2020 Day Observation/Theme 1st Jan Global Family Day World Peace Day 4th Jan World Braille Day 6th Jan Journalists’ Day in Maharashtra 6th Jan The World Day of War Orphans 7th Jan Infant Protection Day 8th Jan African National Congress Foundation Day 9th Jan Pravasi Bharatiya Divas/NRI Day( 16th edition) 10thJan “World Hindi Day” 10thJan World Laughter Day 12th Jan National Youth Day or Yuva Diwas. Theme:"Channelizing Youth Power for Nation Building". 14th Jan Indian Armed Forces Veterans Day 15thJan Indian Army Day(72nd) 16thJan Religious Freedom day 18th Jan 15th Raising Day of NDRF(National Disaster Response Force) 19th Jan National Immunization Day (NID) 21st Jan Tripura, Manipur &Meghalaya 48th statehood day 23rdJan Subhash Chandra Bose Jayanti 24th to 30th National Girl Child Week Jan 24thJan National Girl Child Day Theme:‘Empowering Girls for a Brighter Tomorrow’. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 03.05.2020To09.05.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 03.05.2020to09.05.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr. No. 609/20 PALAKKATTU KOTTAYAM U/S KOTTAYAM Bail from 1 ARAVIND SREENIVASAN 24 PARAMBIL H, PARIPPU TOWN 04.05.20 2336,269,188 SURESH T WEST PS Police station KAVALA, AYMANAM BHAGOM 18:29 Hrs IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 610/20 OLIPARAMBIL H, U/S CHANDAKKADA KOTTAYAM Bail from 2 SUBIN KUMAR PRASANNAN 30 AYMANAM KAVALA 05.05.20 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T VU WEST PS Police station BHAGOM, AYMANAM 22:09 Hrs IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO AYIRAVELICHIRA H, Cr. No. 615/20 PALLICHIRA KARA, THIRUNAKKAR U/S ARUN KOTTAYAM Bail from 3 SUKUMARAN 27 KUMARAKOM, A STAND 06.05.20 2336,269,188 SABU SUNNY SUKUMARAN WEST PS Police station MOOLEPPADOM BHAGOM 18:57 Hrs IPC & 4(2)(a) BHAGOM OF KEPDO KAMMATH H, Cr. No. 616/20 PARAKKADAVU U/S VIJAY V VARGHESE KOTTAYAM Bail from 4 26 BHAGOM, PEROOR STAR Jn. 07.05.20 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T KAMMATH KAMMATH WEST PS Police station KARA, PEROOR 11.20 Hrs IPC & 4(2)(d) VILLEGE OF KEPDO Cr. No. 617/20 PLATHOTTATHIL H, U/S PAYYAPPADY KAVALA KOTTAYAM Bail from 5 THANKACHAN SASIDHARAN 52 STAR Jn. -

Details of Uid Enrolment

Sheet1 DETAILS OF UID ENROLMENT REVENUE DISTRICT KOTTAYAM NAME OF AKSHAYA CENTERS/KELTRON NAME OF SCHOOLS Sl No NAME OF SUB DISTRICT CENTRE Engaged (lp/up/hs/hss/vhss) Full Address with phone number Akshaya Centre, C K Gopinathan Nair Bldg. Sasthankal, Kaippuzha P O_0481 1 KOTTAYAM WEST 33024-ST.GEORGE VHSS KAIPUZHA(HS,VHSS) 2711446 2 KOTTAYAM WEST 33028-NSSHSS KARAPUZHA(HS,HSS) KELTRON 3 KOTTAYAM WEST 33030-GHSS KARAPUZHA(HS,HSS) KELTRON 4 KOTTAYAM WEST 33031-SVGVPHS.KILIROOR(HS) Akshaya e-centre, Chengalam south P O, Chengalam_0481-2526233 5 KOTTAYAM WEST 33032-SNDPHSS KILIROOR(HS,HSS) Akshaya e-centre, Chengalam south P O, Chengalam_0481-2526233 6 KOTTAYAM WEST 33033-CMSCHSS KOTTAYAM(HS,HSS) KELTRON Akshaya e-centre, Devaswom Board Complex, 7 KOTTAYAM WEST 33035-CMSHS OLESSA(HS) Aymanam P O, Kottayam_4812515327 Akshaya e-centre, Devaswom Board Complex, 8 KOTTAYAM WEST 33036-HIGH SCHOOL PARIPPU(HS) Aymanam P O, Kottayam_4812515327 Akshaya e-centre, Samkranthy, Kumaranalloor P O, Kottayam-686028_0481- 9 KOTTAYAM WEST 33044-SHMOUNT HSS.NATTASSERY(HS,HSS) 2590320 10 KOTTAYAM WEST 33047-ST. THOMAS GIRLS H S PUTHANANGADY(HS) KELTRON Akshaya e-centre, Devaswom Board Complex, 11 KOTTAYAM WEST 33048-GHSS KUDAMALOOR(HS,HSS) Aymanam P O, Kottayam_4812515327 Akshaya e-centre, Samkranthy, Kumaranalloor P O, Kottayam-686028_0481- 12 KOTTAYAM WEST 33049-DVVHSS.KUMARANALOOR(HS,VHSS) 2590320 Akshaya e-centre, Samkranthy, Kumaranalloor P O, Kottayam-686028_0481- 13 KOTTAYAM WEST 33050-HOLY FAMILY H S PARAMPUZHA(HS) 2590319 14 KOTTAYAM WEST 33051-GOVT.VHSS -

From Beit Abhe to Angamali: Connections, Functions and Roles of the Church of the East’S Monasteries in Ninth Century Christian-Muslim Relations

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Cochrane, Steve (2014) From Beit Abhe to Angamali: connections, functions and roles of the Church of the East’s monasteries in ninth century Christian-Muslim relations. PhD thesis, Middlesex University / Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/13988/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated.