Scangate Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seminars&Workshops

Seminars&workshops TEMA Arbeta för ett välkomnande Europa med jämlikhet för flyktingar och migranter – kämpa mot alla former av rasism och diskriminering. THEME 9 Working for a Europe of inclusiveness and equality for refugees and migrants – fighting against all forms of racism and discrimination. TEMAN THEMES Forumets seminarier, möten och övriga aktiviteter The seminars, meetings and other activities during the Forum are structured along these themes: har delats in i följande teman: 1 Arbeta för social inkludering och 6 Bygga fackliga strategier för 1 Working for social inclusion and 6 Building labour strategies for sociala rättigheter – välfärd, offentlig anständiga arbeten och värdighet för social rights – welfare, public services decent work and dignity for all – against service och gemensamma tillgångar för alla – mot utsatthet, otrygghet och and common goods for all. precarity and exploitation. alla. exploatering. 2 Working for a sustainable world, 7 Economic alternatives based on 2 Arbeta för en hållbar värld, mat- 7 Ekonomiska alternativ grundade food sovereignity, environmental and peoples needs and rights, for economic suveränitet och för ett rättvist miljö- och på människors behov och rättigheter, climate justice. and social justice. klimatutrymme. för ekonomisk och social rättvisa. 3 Building a democratic and rights 8 Democratizing knowledge, culture, 3 Bygga ett demokratiskt och rättig- 8 Demokratisera kunskap, kultur, based Europe, against “securitarian” education information and mass media. hetsbaserat Europa, mot övervaknings- utbildning, information och massmedia. policies. For participation, openness, samhället och rådande säkerhetspolitik. equality, freedom and minority rights. 9 Working for a Europe of inclu- För deltagande, öppenhet, jämlikhet, 9 Arbeta för ett välkomnande Eu- siveness and equality for refugees and frihet och minoriteters rättigheter. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Party Organisation and Party Adaptation: Western European Communist and Successor Parties Daniel James Keith UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, April, 2010 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature :……………………………………… iii Acknowledgements My colleagues at the Sussex European Institute (SEI) and the Department of Politics and Contemporary European Studies have contributed a wealth of ideas that contributed to this study of Communist parties in Western Europe. Their support, generosity, assistance and wealth of knowledge about political parties made the SEI a fantastic place to conduct my doctoral research. I would like to thank all those at SEI who have given me so many opportunities and who helped to make this research possible including: Paul Webb, Paul Taggart, Aleks Szczerbiak, Francis McGowan, James Hampshire, Lucia Quaglia, Pontus Odmalm and Sally Marthaler. -

Future Party Leaders Or Burned Out?

Lund University STVM25 Department of Political Science Tutor: Michael Hansen/Moira Nelson Future party leaders or burned out? A mixed methods study of the leading members of the youth organizations of political parties in Sweden Elin Fjellman Abstract While career-related motives are not given much attention in studies on party membership, there are strong reasons to believe that such professional factors are important for young party members. This study is one of the first comprehensive investigations of how career-related motives impact the willingness of Swedish leading young party members to become politicians in the future. A unique survey among the national board members of the youth organizations confirms that career-related motives make a positive impact. However, those who experienced more internal stress were unexpectedly found to be more willing to become politicians in the future. The most interesting indication was that the factor that made the strongest impact on the willingness was the integration between the youth organization and its mother party. Another important goal was to develop an understanding of the meaning of career-related motives for young party members. Using a set of 25 in-depth interviews with members of the youth organizations, this study identifies a sense among the members that holding a high position within a political party could imply professional reputational costs because some employers would not hire a person who is “labelled as a politician”. This notation of reputational costs contributes importantly to the literature that seeks to explain party membership. Key words: Sweden, youth organizations, political recruitment, career-related motives, stress, party integration Words: 19 995 . -

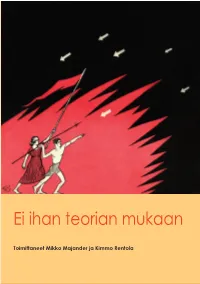

Ei Ihan Teorian Mukaan

Onko työväenliike vain menneisyyttä? Miten punaisten surmapaikoilla on muisteltu? Mitä paljastuu Hampurin arkisen talon taustalta? Miten brittiläinen ammattiyhdistysmies näki talvisodan? Ei ihan teorian mukaan Mihin historiaa käytetään Namibiassa? Miten David Oistrah pääsi soittamaan länteen? Miksi Anna Ahmatova koskettaa? Miten Helsingin katujen hallinnasta kamppailtiin 1962? Tällaisiin ja moniin muihin kysymyksiin haetaan vastauksia tämän kirjan artikkeleissa, jotka liittyvät työväenliikkeen, kommunismin ja neuvostokulttuurin vaiheisiin. Suomalaisten asiantuntijoiden rinnalla kirjoittajia on Ranskasta, Britanniasta ja Norjasta. Aiheiden lisäksi kirjoituksia yhdistää historiantutkija Tauno Saarela, jonka teemoja lähestytään eri näkökulmista. Ei ihan teorian mukaan – asiat ovat usein menneet toisin kuin luulisi. Ei ihan teorian mukaan Toimittaneet Mikko Majander ja Kimmo Rentola TYÖVÄEN HISTORIAN JA PERINTEEN TUTKIMUKSEN SEURA Ei ihan teorian mukaan Ei ihan teorian mukaan Toimittaneet Mikko Majander ja Kimmo Rentola Kollegakirja Tauno Saarelalle 28. helmikuuta 2012 Työväen historian ja perinteen tutkimuksen seura Yhteiskunnallinen arkistosäätiö Helsinki 2012 Toimituskunta: Marita Jalkanen, Pirjo Kaihovaara, Mikko Majander, Raimo Parikka, Kimmo Rentola Copyright kirjoittajat Taitto: Raimo Parikka Kannen kuva: Nuoren työläisen joulu 1926, kansikuva, piirros L. Vickberg Painettua julkaisua myy ja välittää: Unigrafian kirjamyynti http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISBN 978-952-5976-01-4 -

Hort and Olofsson on Göran Therborns Early Years

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a chapter published in Class, Sex and Revolutions: A Critical Appraisal of Gören Therborn. Citation for the original published chapter: Hort, S., Olofsson, G. (2016) A Portrait of the Sociologist as a Young Rebel: Göran Therborn 1941-1981. In: Gunnar Olofsson & Sven Hort (ed.), Class, Sex and Revolutions: A Critical Appraisal of Gören Therborn (pp. 19-51). Lund: Arkiv förlag N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published chapter. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-57095 sven hort & gunnar olofsson A Portrait of the Sociologist as a Young Rebel Göran Therborn 1941–1981 As far as Marx in our time is concerned, my impression is that he is maturing, a bit like a good cheese or a vintage wine – not suitable for dionysiac parties or quick gulps at the battlefront. From Marxism to Post-Marxism?, Therborn 2008: ix. The emergence of a global Swedish intellectual and social scientist He belongs to the unbeaten, a survivor of a merciless defeat subli- mated by many in his generation. This book is an interim report, and the pages to come are an attempt to outline the early years and decades of Göran Therborn’s life trajectory, the intricate intertwin- ing of his socio-political engagement and writings with his social scientific work and publications. In this article the emphasis is on the 1960s and early 1970s, on Sweden and the Far North rather than the rest of the world. We present a few preliminary remarks on a career – in the sociological sense – that has not come to a close, far from it, hence still in need of further (re-)considerations and scru- tiny. -

Political Youth Organisations and Alcohol Policy in Nordic Countries

Political youth organisations and alcohol policy in Nordic countries Project report 2019/2020 Nordic Alcohol and Drug Policy Network www.nordan.org THIS is not a scientific study. It has never aimed to be one. This is advocacy groups attempt to analyse the developments in societies and in a way to predict where are we heading in the next five or ten years. The prediction aspect of this is because we are focusing on young people. And even more, on politically active young people. They are, at least theoretically, the ones making the decisions of tomorrow. Are they the future ministers, prime ministers, party leaders, high officials? Probably, yes. They are going to decide the future of the political parties, and as we are finding out, they give their best to do it already today. Perhaps more than ever, the youth voice is critical in today's policymaking. "Politics is in realignment. And perhaps the most underappreciated change is this: Based on recent research at Tufts University's Tisch College of Civic Life, young voters, ages 18- 29, played a significant role in the 2018 midterms and are poised to shape elections in 2020 and beyond." CNN on January 2, 2020, looking at the US presidential elections. Every Nordic country is discussing or already experimenting with lowering the voting age, thus involving younger people in our democratic processes. That will mean that political parties will listen more and more what young are saying, what they support and are interested in. Youth matter. Today more than ever before. For us, to understand the motives and interests of young people, it will be easier to predict the next steps and the future developments. -

Germany's Party of Democratic Socialism

GERMANY'S PARTY OF DEMOCRATIC SOCIALISM Eric Canepa A great many people expected in 1989 that the break with the old East-bloc communist parties might lead to some strong forces for the renewal of socialism. Many people in the West were surprised at the time that there was so little expression of this. In the German Democratic Republic there was, in fact, a strong democratic socialist current in the demonstrations of the Fall of 1989. Although in the context of the abrupt unification with West Germany this current was smothered, it nevertheless re-emerged via the Party of DemocraticSocialism (PDS). This is a development that bears very careful examination. The following essay is an attempt to illuminate the PDS's potential as a socialist organisation. It is impossible to cover here the legal-political struggles between the PDS and the state as regards expropriation at- tempts, attempts to delegitimise or criminalise some of its leaders, etc., nor the mainstream media distortion of the PDS. The main purpose, rather, must be to describe and analyse this organisation's programme, its actual political practice, the character of its membership, its relationship to the rest of the left, and the attitudes of the population, principally in the East, towards it. The Political Culture of GDR Intellectuals To understand the PDS, it is necessary to begin by noting the rather special characteristics of the GDR intelligentsia which contained more critically- minded Marxists than that of any other East-bloc country. In the first weeks of the Wende (Wende = the 1989 "turning point" in the GDR) it was possible to hear expressions of socialist sentiment on the part of several of the citizen-movement leaders. -

Educated Youth and the Cultural Revolution in China

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES MICHIGAN PAPERS IN CHINESE STUDIES Ann Arbor, Michigan Educated Youth and The Cultural Revolution in China Martin Sj University of Michigan Michigan Papers in Chinese Studies No. 10 1971 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright 1971 by Center for Chinese Studies The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89264-010-2 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-472-03814-5 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12760-3 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90155-5 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Contents I. Introduction 1 Mao Tse-tung 1 Mao Tse-tung and the Youth of China 4 The State of Youth 6 Abbreviations Used in Text and Bibliography 9 II. The Cultural Revolution: 1966 10 Peking University 11 National Movement for Educational Reform 13 Leadership Support for Revolutionary Students 15 Early Mass Rallies and Movements 17 Recreating the Long March 21 Attempts to Disperse Students 25 Invocation of the Tradition of the PLA 26 Student Relations with Workers and Peasants 27 III. The Cultural Revolution: 1967 30 Attacks on Egoism 30 Attempts to Control Violence 31 The Three-Way Alliance 32 Attempts to Resume Classes: I 32 Responses to Changed Situations 35 Attempts to Resume Classes: II 36 Shift to the Left — April 39 Factionalism and Violent Struggle 40 Attempts to Resume Classes: III 42 The Wuhan Incident 44 Support the PLA 45 Crackdown on Young People 49 Attempts to Resume Classes: IV 51 Sheng Wu-lien . -

SONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME RD 011 988 24 80 005 497 AUTHOR Bressler, Marvin; Higgins, Judith TITLE The Political Left on Campus and In Society: The Active Decades. Final Report. INSTITUTION Princeton Univ., N.J. SONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO BR-9-0442 PUB DATE Dec 72 GRANT 0EG-2-9-400442-1058(010) NOTE 67p. EDRS PRICE MF -$0.65 MC-353.29 DESCRIPTORS *Activism; College Students; Communism; *Comparative Analysis; Dissent; Generation Gap; *Politica... Attitudes; Political Influences; Political Issues; *Social Action; Social Attitudes; Social Change; .Student Attitudes; Student College Relationship IDENTIFIERS *Counter Culture ABSTRACT A comparative analysis is made of the similarities and differences between youthful activists of the1960's with earlier periods, focusing upon the 1920's and 1930's. Thereport briefly sketches the political and romantic Student Left during thedecade of the sixties; delineates the characteristics of non-campus-based youthful radicalism as exemplified by the action and thoughtof the Young Communist League between 1922 and 1943; explores the nature of the student movements which emerged during the immediately ensuing period; and specifies resemblances and differences between thepast and present in order to better anticipate the future. Whilemuch of the data of the study are derived from conventional bibliographical sources, the main historical sections are based on an intensive analysis of all named issues of youth-oriented radicalperiodicals or newspapers. Findings for both past and present youth groups indicate they were preoccupied with social issues ofpeace, poverty, civil liberties, and racial discrimination, and withcampus issues of corporative control of the university, academic freedom, economic issues, and academic offerings. -

JOHN DEWEY, the NEW LEFT, and the POLITICS of CONTINGENCY and PLURALISM by DANIEL WAYNE RINN a THESIS Presented to the Departmen

JOHN DEWEY, THE NEW LEFT, AND THE POLITICS OF CONTINGENCY AND PLURALISM by DANIEL WAYNE RINN A THESIS Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2012 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Daniel Wayne Rinn Title: John Dewey, the New Left, and the Politics of Contingency and Pluralism This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Department of History by: Ellen Herman Chair Daniel Pope Member Colin Koopman Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2012 ii © 2012 Daniel Wayne Rinn iii THESIS ABSTRACT Daniel Wayne Rinn Master of Arts Department of History December 2012 Title: John Dewey, the New Left, and the Politics of Contingency and Pluralism Most histories of the New Left emphasize that some variant of Marxism ultimately influenced activists in their pursuit of social change. Through careful examination of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), I argue that New Left thought was not always anti-liberal. Founding SDS members hardly rejected liberal political theory during the early years of the movement (1960-1963). New Left thought was profoundly indebted to John Dewey’s political and philosophical method. Deweyan liberalism suggested theory should be directly applicable in the world of social action and truth should always be regarded as contingent. -

Read the Paper

EEPXXX10.1177/0888325415599197East European Politics and SocietiesBan 599197research-article2015 East European Politics and Societies and Cultures Volume 29 Number 3 August 2015 640 –650 © 2015 SAGE Publications Beyond Anticommunism: 10.1177/0888325415599197 http://eeps.sagepub.com hosted at The Fragility of Class Analysis http://online.sagepub.com in Romania Cornel Ban Boston University The debate about socio-economic inequalities and class has become increasingly important in mainstream academic and political debates. This article shows that during the late 2000s class analysis was rediscovered in Romania both as an analytical cate- gory and as a category of practice. The evidence suggests that this was the result of two converging processes: the deepening crisis of Western capitalism after 2008 and the country’s increasingly transnational networks of young scholars, journalists, and civil society actors. Although a steady and focused interest in class analysis is a novelty in Romania’s academia, media, and political life and has the potential to change the political conversation in the future, so far the social fields where this analysis is prac- ticed have remained relatively marginal. Keywords: Romania; class analysis; Great Recession; neoliberalism Rediscovering Class Popular and academic class analyses are constitutive elements of an emerging social opposition to the neoliberal consensus in Romania. In 2012 and 2013, extensive social protests around issues such as the continuing privatization of healthcare or the activities of multinational mining operations raised new and difficult questions about market-society relations and the conditions of working people.1 These protests did not precipitate a paradigmatic breakthrough. Neoliberal and right-wing populist voices continue to suffuse the public sphere while left-leaning critics remain largely marginalized.