Anna Striethorst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radical Closure

Closure adical Closur R e adical R R adical 1 Radical Closure Closure Radical Closure Radical Closure Jalal Toufic Jalal Toufic,Radical-Closure Artist with Bandaged Sense Organ (a Tribute to Van Gogh), no. 1, 2020 Jalal Toufic 2 3 Radical Closure The book includes four of my conceptual artworks. They are based This book is composed of the following previously published texts on Van Gogh’s two paintings Wheatfield with Crows (1889) and Self- on radical closure: “Radical Closure,” in Over-Sensitivity, 2nd edition Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889). The one on the front cover is (Forthcoming Books, 2009); “First Aid, Second Growth, Third Radical-Closure Artist with Bandaged Sense Organ (After Van Gogh’s Degree, Fourth World, Fifth Amendment, Sixth Sense,” “Radical- “Wheatfield with Crows” and “Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear”), 2020; Closure Artist with Bandaged Sense Organ,” “Copyright Free Farm the one that serves as the frontispiece is Radical-Closure Artist with Road,” and pp. 104–105 and 211–214 in Forthcoming, 2nd edition Bandaged Sense Organ (a Tribute to Van Gogh), no. 1, 2020; the one (Berlin: e-flux journal-Sternberg Press, 2014); pp. 82–92 in Distracted, on the last page is Radical-Closure Artist with Bandaged Sense Organ 2nd edition (Berkeley, CA: Tuumba Press, 2003); “Verbatim,” in What (a Tribute to Van Gogh), no. 2, 2020; and the one on the back cover Was I Thinking? (Berlin: e-flux journal-Sternberg Press, 2017); and is Radical-Closure Artist with Bandaged Sense Organ (After Van Gogh’s pp. 88–96 in Postscripts (Stockholm: Moderna Museet; Amsterdam: “Wheatfield with Crows” and “Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear”), 2018. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science German Print Media Coverage in the Bosnia and Kosovo Wars of the 1990S Marg

1 The London School of Economics and Political Science German Print Media Coverage in the Bosnia and Kosovo Wars of the 1990s Margit Viola Wunsch A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2012 2 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. Abstract This is a novel study of the German press’ visual and textual coverage of the wars in Bosnia (1992-95) and Kosovo (1998-99). Key moments have been selected and analysed from both wars using a broad range of publications ranging from extreme-right to extreme-left and including broadsheets, a tabloid and a news-magazine, key moments have been selected from both wars. Two sections with parallel chapters form the core of the thesis. The first deals with the war in Bosnia and the second the conflict in Kosovo. Each section contains one chapter on the initial phase of the conflict, one chapter on an important atrocity – namely the Srebrenica Massacre in Bosnia and the Račak incident in Kosovo – and lastly a chapter each on the international involvement which ended the immediate violence. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Outsider Politics: Radicalism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Outsider politics : Radicalism as a Political Strategy in Western Europe and Latin America A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Verónica Hoyo Committee in charge: Professor William Chandler, Chair Professor Matthew Shugart, Co-Chair Professor Akos Rona-Tas Professor Sebastian Saiegh Professor Kaare Strom 2010 Copyright Verónica Hoyo, 2010 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Verónica Hoyo is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION A mis padres, Irma y Gonzalo, y a mi hermana Irma. Gracias por ser fuente constante de amor, inspiración y apoyo incondicional. Esto nunca hubiera sido posible sin ustedes. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page.............................................................................................................. iii Dedication..................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents.......................................................................................................... v List of Abbreviations...................................................................................................... vi List of Tables................................................................................................................... xii List of Graphs................................................................................................................ -

Seminars&Workshops

Seminars&workshops TEMA Arbeta för ett välkomnande Europa med jämlikhet för flyktingar och migranter – kämpa mot alla former av rasism och diskriminering. THEME 9 Working for a Europe of inclusiveness and equality for refugees and migrants – fighting against all forms of racism and discrimination. TEMAN THEMES Forumets seminarier, möten och övriga aktiviteter The seminars, meetings and other activities during the Forum are structured along these themes: har delats in i följande teman: 1 Arbeta för social inkludering och 6 Bygga fackliga strategier för 1 Working for social inclusion and 6 Building labour strategies for sociala rättigheter – välfärd, offentlig anständiga arbeten och värdighet för social rights – welfare, public services decent work and dignity for all – against service och gemensamma tillgångar för alla – mot utsatthet, otrygghet och and common goods for all. precarity and exploitation. alla. exploatering. 2 Working for a sustainable world, 7 Economic alternatives based on 2 Arbeta för en hållbar värld, mat- 7 Ekonomiska alternativ grundade food sovereignity, environmental and peoples needs and rights, for economic suveränitet och för ett rättvist miljö- och på människors behov och rättigheter, climate justice. and social justice. klimatutrymme. för ekonomisk och social rättvisa. 3 Building a democratic and rights 8 Democratizing knowledge, culture, 3 Bygga ett demokratiskt och rättig- 8 Demokratisera kunskap, kultur, based Europe, against “securitarian” education information and mass media. hetsbaserat Europa, mot övervaknings- utbildning, information och massmedia. policies. For participation, openness, samhället och rådande säkerhetspolitik. equality, freedom and minority rights. 9 Working for a Europe of inclu- För deltagande, öppenhet, jämlikhet, 9 Arbeta för ett välkomnande Eu- siveness and equality for refugees and frihet och minoriteters rättigheter. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zoeb Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) dr section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Party Organisation and Party Adaptation: Western European Communist and Successor Parties Daniel James Keith UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, April, 2010 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature :……………………………………… iii Acknowledgements My colleagues at the Sussex European Institute (SEI) and the Department of Politics and Contemporary European Studies have contributed a wealth of ideas that contributed to this study of Communist parties in Western Europe. Their support, generosity, assistance and wealth of knowledge about political parties made the SEI a fantastic place to conduct my doctoral research. I would like to thank all those at SEI who have given me so many opportunities and who helped to make this research possible including: Paul Webb, Paul Taggart, Aleks Szczerbiak, Francis McGowan, James Hampshire, Lucia Quaglia, Pontus Odmalm and Sally Marthaler. -

Future Party Leaders Or Burned Out?

Lund University STVM25 Department of Political Science Tutor: Michael Hansen/Moira Nelson Future party leaders or burned out? A mixed methods study of the leading members of the youth organizations of political parties in Sweden Elin Fjellman Abstract While career-related motives are not given much attention in studies on party membership, there are strong reasons to believe that such professional factors are important for young party members. This study is one of the first comprehensive investigations of how career-related motives impact the willingness of Swedish leading young party members to become politicians in the future. A unique survey among the national board members of the youth organizations confirms that career-related motives make a positive impact. However, those who experienced more internal stress were unexpectedly found to be more willing to become politicians in the future. The most interesting indication was that the factor that made the strongest impact on the willingness was the integration between the youth organization and its mother party. Another important goal was to develop an understanding of the meaning of career-related motives for young party members. Using a set of 25 in-depth interviews with members of the youth organizations, this study identifies a sense among the members that holding a high position within a political party could imply professional reputational costs because some employers would not hire a person who is “labelled as a politician”. This notation of reputational costs contributes importantly to the literature that seeks to explain party membership. Key words: Sweden, youth organizations, political recruitment, career-related motives, stress, party integration Words: 19 995 . -

Lost in Space Pairwise Comparisons of Parties As an Alternative to Left-Right Measures of Political Difference

Lost in Space Pairwise Comparisons of Parties as an Alternative to Left-Right Measures of Political Difference by Martin M¨older Submitted to Central European University Doctoral School of Political Science, Public Policy and International Relations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Dr. Zsolt Enyedi CEU eTD Collection Word count: ∼ 73,000 Budapest, Hungary 2017 I, the undersigned [Martin M¨older],candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Central European University Doctoral School of Political Science, Public Policy and International Relations, declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person's or institution's copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 27 April 2017 ||||||||||||||||| Signature CEU eTD Collection © by Martin M¨older,2017 All Rights Reserved. i Lost in Space Pairwise Comparisons of Parties as an Alternative to Left-Right Measures of Political Difference by Martin M¨older 2017 CEU eTD Collection Am I following all of the right leads? Or am I about to get lost in space? When my time comes, they'll write my destiny Will you take this ride? Will you take this ride with me? { \Lost In Space", The Misfits (Album: Famous Monsters, 1999) ii Acknowledgments The idea explored in this thesis { that it makes more sense to compare parties to each other than to an assumed dimension { came from a simple intuition while I was working with the manifesto data set and still mostly oblivious to the jungle of spatial analysis of party politics. -

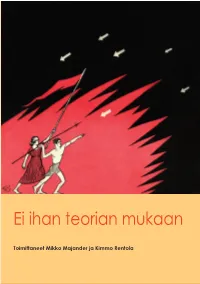

Ei Ihan Teorian Mukaan

Onko työväenliike vain menneisyyttä? Miten punaisten surmapaikoilla on muisteltu? Mitä paljastuu Hampurin arkisen talon taustalta? Miten brittiläinen ammattiyhdistysmies näki talvisodan? Ei ihan teorian mukaan Mihin historiaa käytetään Namibiassa? Miten David Oistrah pääsi soittamaan länteen? Miksi Anna Ahmatova koskettaa? Miten Helsingin katujen hallinnasta kamppailtiin 1962? Tällaisiin ja moniin muihin kysymyksiin haetaan vastauksia tämän kirjan artikkeleissa, jotka liittyvät työväenliikkeen, kommunismin ja neuvostokulttuurin vaiheisiin. Suomalaisten asiantuntijoiden rinnalla kirjoittajia on Ranskasta, Britanniasta ja Norjasta. Aiheiden lisäksi kirjoituksia yhdistää historiantutkija Tauno Saarela, jonka teemoja lähestytään eri näkökulmista. Ei ihan teorian mukaan – asiat ovat usein menneet toisin kuin luulisi. Ei ihan teorian mukaan Toimittaneet Mikko Majander ja Kimmo Rentola TYÖVÄEN HISTORIAN JA PERINTEEN TUTKIMUKSEN SEURA Ei ihan teorian mukaan Ei ihan teorian mukaan Toimittaneet Mikko Majander ja Kimmo Rentola Kollegakirja Tauno Saarelalle 28. helmikuuta 2012 Työväen historian ja perinteen tutkimuksen seura Yhteiskunnallinen arkistosäätiö Helsinki 2012 Toimituskunta: Marita Jalkanen, Pirjo Kaihovaara, Mikko Majander, Raimo Parikka, Kimmo Rentola Copyright kirjoittajat Taitto: Raimo Parikka Kannen kuva: Nuoren työläisen joulu 1926, kansikuva, piirros L. Vickberg Painettua julkaisua myy ja välittää: Unigrafian kirjamyynti http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISBN 978-952-5976-01-4 -

The General Elections in Portugal 2019 by Mariana Mendes

2019-5 MIDEM-Report THE GENERAL ELECTIONS IN PORTUGAL 2019 BY MARIANA MENDES MIDEM is a research center of Technische Universität Dresden in cooperation with the University of Duisburg-Essen, funded by Stiftung Mercator. It is led by Prof. Dr. Hans Vorländer, TU Dresden. Citation: Mendes, Mariana 2019: The General Elections in Portugal 2019, MIDEM-Report 2019-5, Dresden. CONTENTS SUMMARY 4 1. THE PORTUGUESE PARTY SYSTEM 4 2. THE LACK OF SALIENCE AND POLITICIZATION OF IMMIGRATION 7 3. THE ELECTORAL RESULTS 10 4. OUTLOOK 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY 11 AUTHOR 12 IMPRINT 13 SUMMARY The 2019 Portuguese legislative elections confirm the resilience of its party system and, in particular, of the center-left Partido Socialista (PS), one of the few social democratic parties in Europe that did not lose electoral relevance in the past decade. Its vote share of almost 37 % strengthens the party’s position and confirms the positive evaluation that voters made of its 2015-2019 mandate. Parties on the right-wing side of the spectrum were the most significant losers. The center-right Partido Social Democrata (PSD) and the conservative Partido Popular (CDS-PP) lost in seats, going from a joint 38,5% in 2015 to a combined result that does not add up to more than 32 % in 2019. The CDS-PP was hit particularly hard. One of the lingering questions during the election was whether the two largest parties on the radical left – the Communists and the Left Bloc – would be punished or rewarded for the parliamentary agreement established with the PS during the 2015-2019 mandate. -

Hort and Olofsson on Göran Therborns Early Years

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a chapter published in Class, Sex and Revolutions: A Critical Appraisal of Gören Therborn. Citation for the original published chapter: Hort, S., Olofsson, G. (2016) A Portrait of the Sociologist as a Young Rebel: Göran Therborn 1941-1981. In: Gunnar Olofsson & Sven Hort (ed.), Class, Sex and Revolutions: A Critical Appraisal of Gören Therborn (pp. 19-51). Lund: Arkiv förlag N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published chapter. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-57095 sven hort & gunnar olofsson A Portrait of the Sociologist as a Young Rebel Göran Therborn 1941–1981 As far as Marx in our time is concerned, my impression is that he is maturing, a bit like a good cheese or a vintage wine – not suitable for dionysiac parties or quick gulps at the battlefront. From Marxism to Post-Marxism?, Therborn 2008: ix. The emergence of a global Swedish intellectual and social scientist He belongs to the unbeaten, a survivor of a merciless defeat subli- mated by many in his generation. This book is an interim report, and the pages to come are an attempt to outline the early years and decades of Göran Therborn’s life trajectory, the intricate intertwin- ing of his socio-political engagement and writings with his social scientific work and publications. In this article the emphasis is on the 1960s and early 1970s, on Sweden and the Far North rather than the rest of the world. We present a few preliminary remarks on a career – in the sociological sense – that has not come to a close, far from it, hence still in need of further (re-)considerations and scru- tiny.