Crag-And-Tail Features on the Amundsen Sea Continental Shelf, West Antarctica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY of the SCOTT GLACIER and WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA

This dissertation has been /»OOAOO m icrofilm ed exactly as received MINSHEW, Jr., Velon Haywood, 1939- GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Geology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Velon Haywood Minshew, Jr. B.S., M.S, The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by -Adviser Department of Geology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report covers two field seasons in the central Trans- antarctic Mountains, During this time, the Mt, Weaver field party consisted of: George Doumani, leader and paleontologist; Larry Lackey, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant. The Wisconsin Range party was composed of: Gunter Faure, leader and geochronologist; John Mercer, glacial geologist; John Murtaugh, igneous petrclogist; James Teller, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant; Harry Gair, visiting strati- grapher. The author served as a stratigrapher with both expedi tions . Various members of the staff of the Department of Geology, The Ohio State University, as well as some specialists from the outside were consulted in the laboratory studies for the pre paration of this report. Dr. George E. Moore supervised the petrographic work and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr. J. M. Schopf examined the coal and plant fossils, and provided information concerning their age and environmental significance. Drs. Richard P. Goldthwait and Colin B. B. Bull spent time with the author discussing the late Paleozoic glacial deposits, and reviewed portions of the manuscript. -

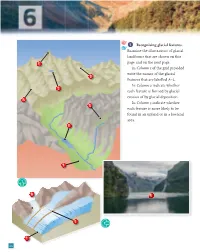

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Trip F the PINNACLE HILLS and the MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A

F-1 Trip F THE PINNACLE HILLS AND THE MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A. Sanders Department of Geosciences Monroe Community College INTRODUCTION The Pinnacle Hills, fortunately, were voluminously described with many excellent photographs by Fairchild, (1923). In 1973 the Range still stands as a conspicuous east-west ridge extending from the town of Brighton, at about Hillside Avenue, four miles to the Genesee River at the University of Rochester campus, referred to as Oak Hill. But, for over thirty years the Range was butchered for sand and gravel, which was both a crime and blessing from the geological point of view (plates I-VI). First, it destroyed the original land form shapes which were subsequently covered with man-made structures drawing the shade on its original beauty. Secondly, it allowed study of its structure by a man with a brilliantly analytical mind, Herman L. Fair child. It is an excellent example of morainal deposition at an ice front in a state of dynamic equilibrium, except for minor fluctuations. The Mendon Kame area on the other hand, represents the result of a block of stagnant ice, probably detached and draped over drumlins and drumloidal hills, melting away with tunnels, crevasses, and per foration deposits spilling or squirting their included debris over a more or less square area leaving topographically high kames and esker F-2 segments with many kettles and a large central area of impounded drainage. There appears to be several wave-cut levels at around the + 700 1 Lake Dana level, (Fairchild, 1923). The author in no way pretends to be a Pleistocene expert, but an attempt is made to give a few possible interpretations of the many diverse forms found in the Mendon Kames area. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

Glacial Processes and Landforms-Transport and Deposition

Glacial Processes and Landforms—Transport and Deposition☆ John Menziesa and Martin Rossb, aDepartment of Earth Sciences, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada; bDepartment of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada © 2020 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Introduction 2 2 Towards deposition—Sediment transport 4 3 Sediment deposition 5 3.1 Landforms/bedforms directly attributable to active/passive ice activity 6 3.1.1 Drumlins 6 3.1.2 Flutes moraines and mega scale glacial lineations (MSGLs) 8 3.1.3 Ribbed (Rogen) moraines 10 3.1.4 Marginal moraines 11 3.2 Landforms/bedforms indirectly attributable to active/passive ice activity 12 3.2.1 Esker systems and meltwater corridors 12 3.2.2 Kames and kame terraces 15 3.2.3 Outwash fans and deltas 15 3.2.4 Till deltas/tongues and grounding lines 15 Future perspectives 16 References 16 Glossary De Geer moraine Named after Swedish geologist G.J. De Geer (1858–1943), these moraines are low amplitude ridges that developed subaqueously by a combination of sediment deposition and squeezing and pushing of sediment along the grounding-line of a water-terminating ice margin. They typically occur as a series of closely-spaced ridges presumably recording annual retreat-push cycles under limited sediment supply. Equifinality A term used to convey the fact that many landforms or bedforms, although of different origins and with differing sediment contents, may end up looking remarkably similar in the final form. Equilibrium line It is the altitude on an ice mass that marks the point below which all previous year’s snow has melted. -

Glaciers I: Intro, Geology and Mass Balance

T. Perron – 12.001 – Glaciers 1 Glaciers I: Intro, Geology and Mass Balance I. Why study glaciers? • Role in freshwater budget o Fraction of earth’s water that is fresh (non-saline): 3% o Fraction of earth’s freshwater that is ice: ~2/3 o Fraction of earth’s surface covered by ice: ~8% • Climate records, climate effects & feedbacks: more in climate lecture • Postglacial rebound helps constrain mantle viscosity • Major driver of erosion, sediment transport, and landscape evolution • But how important have glaciers been over Earth’s history? o Over very long timescales, there seems to be a rhythm to glaciations . From geologic evidence: 950 Ma, 750, 650, 450, 350-250, 4-? . Proposed to reflect arrangement of continents (supercontinents promote accumulation of continental ice). But we don’t even have a very good record of this beyond a few hundred Myr, let alone precise climate records o We have better records for more recent intervals . Antarctic glaciation began 25 Ma, Greenland 20Ma, Alaska 7Ma. Major Northern hemisphere glaciations began ~4Myr. And this has been the typical climate state since! . Again, more in climate lecture. For now, suffice to say that glacial periods have dominated recent climate history. We’re in an interglacial, the first major one since ~125 ka. And our interglacial is an anomalously warm one. We must remind ourselves of this when examining landforms today. o What was North America like during glacial conditions? During LGM, we know there were . Extensive ice sheets [PPT] . Alpine glaciers in mountains beyond the ice margin . Large glacially-dammed lakes (Missoula, Bonneville) [PPT] . -

Glacial Geology of Adams Inlet, Southeastern Alaska

Institute of Polar Studies Report No. 25 Glacial Geology of Adams Inlet, Southeastern Alaska l/h':'~~~~2l:gtf"'" SN" I" '" '" 7, r.• "'. ~ i~' _~~ ... 1!!JW'IIA8 ~ ' ... ':~ ~l·::,.:~·,~I"~,.!};·'o":?"~~"''''''''''''~ r .! np:~} 3TATE Uf-4lVERSnY by t) '{;fS~MACf< ROAD \:.~i~bYMaUi. OHlOGltltM Garry D. McKenzie " Institute of Polar Studies November 1970 GOLDTHWAIT POLAR LIBRARY The Ohio State University BYRD POLAR RESEARCH CENTER Research Foundation THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Columbus, Ohio 43212 1090 CARMACK ROAD COLUMBUS, OHIO 43210 USA INSTITUTE OF POLAR STUDIES Report No. 25 GLACIAL GEOLOGY OF ADAMS INLET, SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA by Garry D. McKenzie Institute of Polar Studies November 1970 The Ohio State University Research Foundation Columbus, Ohio 43212 ABSTRACT Adams Inlet is in the rolling and rugged Chilkat-Baranof Mountains in the eastern part of Glacier Bay National Monument, Alaska. Rapid deglaciation of the area in the first half of the twentieth century has exposed thick sections of post-Hypsithermal deposits and some of the oldest unconsolidated deposits in Glacier Bay. About 30 percent of the area is underlain by uncon solidated material; 14 percent of the area is still covered with ice. The formations present in Adams Inlet are, from the oldest to the youngest: Granite Canyon till, Forest Creek glaciomarine sediments, Van Horn Formation (lower gravel member), Adams lacustrine-till complex, Berg gravel and sand, Glacier Bay drift, and Seal River gravel. No evidence of an early post-Wisconsin ice advance, indicated by the Muir Formation in nearby Muir Inlet, is present in Adams Inlet. Following deposition of the late Wisconsin Granite Canyon till, the Forest Creek glaciomarine sediments were laid down in water 2 to 20 m deep; they now occur as much as 30 m above present sea level. -

Glaciers and Glacial Erosional Landforms

GLACIERS AND GLACIAL EROSIONAL LANDFORMS Dr. NANDINI CHATTERJEE Associate Professor Department of Geography Taki Govt College Taki, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal Part I Geography Honours Paper I Group B -Geomorphology Topic 5- Development of Landforms GLACIER AND ICE CAPS Glacier is an extended mass of ice formed from snow falling and accumulating over the years and moving very slowly, either descending from high mountains, as in valley glaciers, or moving outward from centers of accumulation, as in continental glaciers. • Ice Cap - less than 50,000 km2. • Ice Sheet - cover major portion of a continent. • Ice thicker than topography. • Ice flows in direction of slope of the glacier. • Greenland and Antarctica - 3000 to 4000 m thick (10 - 13 thousand feet or 1.5 to 2 miles!) FORMATION AND MOVEMENT OF GLACIERS • Glaciers begin to form when snow remains Once the glacier becomes heavy enough, it in the same area year-round, where starts to move. There are two types of enough snow accumulates to transform glacial movement, and most glacial into ice. Each year, new layers of snow bury movement is a mixture of both: and compress the previous layers. This Internal deformation, or strain, in glacier compression forces the snow to re- ice is a response to shear stresses arising crystallize, forming grains similar in size and from the weight of the ice (ice thickness) shape to grains of sugar. Gradually the and the degree of slope of the glacier grains grow larger and the air pockets surface. This is the slow creep of ice due to between the grains get smaller, causing the slippage within and between the ice snow to slowly compact and increase in crystals. -

Geographical Terms A

Geographical Terms A abrasion Wearing of rock surfaces by agronomy Agric. economy, including friction, where abrasive material is theory and practice of animal hus transported by running water, ice, bandry, crop production and soil wind, waves, etc. management. abrasion platform Coastal rock plat aiguille Prominent needle-shaped form worn nearly smooth by abrasion. rock-peak, usually above snow-line and formed by frost action. absolute humidity Amount of water vapour per unit volume ofair. ait Small island in river or lake. abyssal Ocean deeps between 1,200 alfalfa Deep-rooted perennial plant, and 3,000 fathoms, where sunlight does largely used as fodder-crop since its not penetrate and there is no plant life. deep roots withstand drought. Pro duced mainly in U.S.A. and Argentina. accessibility Nearness or centrality of one function or place to other functions allocation-location problem Problem or places measured in terms ofdistance, of locating facilities, services, factories time, cost, etc. etc. in any area so that transport costs are minimized, thresholds are met and acre-foot Amount of water required total population is served. to cover I acre of land to depth of I ft. (43,560 cu. ft.). alluvial cone Form of alluvial fan, consisting of mass of thick coarse adiabatic Relating to chan~e occurr material. ing in temp. of a mass of gas, III ascend ing or descending air masses, without alluvial fan Mass of sand or gravel actual gain or loss ofheat from outside. deposited by stream where it leaves constricted course for main valley. afforestation Deliberate planting of trees where none ever grew or where alluvium Sand, silt and gravel laid none have grown recently. -

A Comparative Analysis of Selected Drumlin Fields in North America

MORPHOLOGY OF DRUMLINS: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SELECTED 415 DRUMLIN FIELDS IN NORTH AMERICA Morphology of Drumlins: A Comparative Analysis of Selected Drumlin Fields in North America Amy Annen Faculty Sponsor: Dean Wilder, Department of Geography and Earth Science ABSTRACT Pleistocene glaciers revealed numerous types of land formations in their retreat northward during climatic warming. The postglacial landscape contains various features, such as moraines, flutes, and drumlin fields. Drumlin fields in southeast- ern Wisconsin and west central New York are compared in terms of drumlin morphology to ascertain regional differences between drumlin fields formed by dif- ferent lobes of the Wisconsinan Laurentide ice sheet. Topographic maps of the Wisconsin and New York study areas are used to measure physical characteristics of individual drumlins. Drumlins from the two glacial lobes differ significantly on the basis of length, width, and relief, but are similar in terms of nearest neighbor proximity and width/length ratios. Differences between the drumlin belts in Wisconsin and New York may result from natural variations in glacial conditions during formation, although the specific mechanisms remain elusive. INTRODUCTION Repeated advances and retreats of continental ice sheets characterized the late Pleistocene epoch (130,000 to 10,000 years BP.). The Pleistocene ice expansion during Wisconsin Glaciation occurred approximately 20,000 to 10,000 years BP. At about 17,000 to 18,000 years BP., the Laurentide ice sheet extended to its maximum position south of the Great Lakes, marked by a terminal moraine (Easterbrook, 1993, Benn and Evans, 1998). In the years following maximum advance, the ice sheet revealed numerous types of land formations in the retreat northward during climatic warming. -

Using Knowledge of Glacial Processes in Mineral Exploration

PROSPECTING UNDER COVER: Using Knowledge of Glacial Processes in Mineral Exploration Notes to accompany CIM Short Course November 5 2014 Denise Brushett Geological Survey of Newfoundland and Labrador Introduction As a glacier advances it grinds down and erodes the bedrock beneath the ice. Conceivably, ore deposits are also eroded, resulting in mineralized grains and boulders being picked up and incorporated into the advancing ice. With melting and subsequent ice retreat, all entrapped rock and mineral grains, fragments and boulders will be deposited in the form of thin or occasionally thick veneers of glacial sediment. In large areas of Newfoundland and Labrador the bedrock surface is covered with unconsolidated glacial sediment which also prevents direct observation of bedrock and therefore, of potential economic mineral deposits. A general understanding of the origin of glacial sediments provides the background necessary for use as an effective tool for mineral exploration and is necessary in order to identify economically significant minerals or geochemical anomalies within these sediments and to trace these minerals back to their source, which may be exposed bedrock or drift-covered bedrock. Glaciers & Glaciation: General Principles There were multiple glaciations in the Quaternary Period (last 1.9 Ma) during which Canada experienced at least four periods of glaciation, each followed by long interglacial periods where climatic conditions were much warmer than they are today (Figure 1). The four major glacial episodes, from oldest to youngest, have been termed the Nebraskan, Kansan, Illinoian, and Wisconsinan. Some earlier glaciations (e.g., Illinoian) were more extensive than the latest one (Wisconsinan). Up to 97% of Canada was covered during these glacial extremes, whereas today only 1% of the land surface is covered by glacial ice, mainly in the Queen Elizabeth Islands, Baffin Island and mountainous regions in western Canada and the Torngat Mountains of Labrador. -

Seafloor Geomorphology of Western Antarctic Peninsula Bays

The Cryosphere, 12, 205–225, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-205-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Seafloor geomorphology of western Antarctic Peninsula bays: a signature of ice flow behaviour Yuribia P. Munoz and Julia S. Wellner Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Houston, Houston, Texas 77204, USA Correspondence: Yuribia P. Munoz ([email protected]) Received: 12 June 2017 – Discussion started: 22 June 2017 Revised: 4 November 2017 – Accepted: 13 November 2017 – Published: 22 January 2018 Abstract. Glacial geomorphology is used in Antarctica to 1 Introduction reconstruct ice advance during the Last Glacial Maximum and subsequent retreat across the continental shelf. Analo- While warming temperatures in the Antarctic Peninsula (AP) gous geomorphic assemblages are found in glaciated fjords have resulted in the retreat of 90 % of the regional glaciers and are used to interpret the glacial history and glacial dy- (Cook et al., 2014) and the collapse of ice shelves (Morris namics in those areas. In addition, understanding the distri- and Vaughan, 2003; Cook and Vaughan, 2010), recent stud- bution of submarine landforms in bays and the local con- ies have shown that since the late 1990s this region is cur- trols exerted on ice flow can help improve numerical models rently experiencing a cooling trend (Turner et al., 2016). The by providing constraints through these drainage areas. We AP is a dynamic region that serves as a natural laboratory present multibeam swath bathymetry from several bays in to study ice flow and the resulting sediment deposits.