Glacial Processes and Landforms-Transport and Deposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Break-Up of the Norwegian Channel Ice Stream During the Last Glacial Maximum

Quaternary Science Reviews 107 (2015) 231e242 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Early break-up of the Norwegian Channel Ice Stream during the Last Glacial Maximum * John Inge Svendsen a, , Jason P. Briner b, Jan Mangerud a, Nicolas E. Young c a Department of Earth Science, University of Bergen and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Postbox 7803, N-5020 Bergen, Norway b Department of Geology, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA c Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY, USA article info abstract Article history: We present 18 new cosmogenic 10Be exposure ages that constrain the breakup time of the Norwegian Received 11 June 2014 Channel Ice Stream (NCIS) and the initial retreat of the Scandinavian Ice Sheet from the Southwest coast Received in revised form of Norway following the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). Seven samples from glacially transported erratics 31 October 2014 on the island Utsira, located in the path of the NCIS about 400 km up-flow from the LGM ice front Accepted 3 November 2014 position, yielded an average 10Be age of 22.0 ± 2.0 ka. The distribution of the ages is skewed with the 4 Available online youngest all within the range 20.2e20.8 ka. We place most confidence on this cluster of ages to constrain the timing of ice sheet retreat as we suspect the 3 oldest ages have some inheritance from a previous ice Keywords: Norwegian Channel Ice Stream free period. Three additional ages from the adjacent island Karmøy provided an average age of ± 10 Scandinavian Ice Sheet 20.9 0.7 ka, further supporting the new timing of retreat for the NCIS. -

Ribbed Bedforms in Palaeo-Ice Streams Reveal Shear Margin

https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2020-336 Preprint. Discussion started: 21 November 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Ribbed bedforms in palaeo-ice streams reveal shear margin positions, lobe shutdown and the interaction of meltwater drainage and ice velocity patterns Jean Vérité1, Édouard Ravier1, Olivier Bourgeois2, Stéphane Pochat2, Thomas Lelandais1, Régis 5 Mourgues1, Christopher D. Clark3, Paul Bessin1, David Peigné1, Nigel Atkinson4 1 Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique, UMR 6112, CNRS, Le Mans Université, Avenue Olivier Messiaen, 72085 Le Mans CEDEX 9, France 2 Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique, UMR 6112, CNRS, Université de Nantes, 2 rue de la Houssinière, BP 92208, 44322 Nantes CEDEX 3, France 10 3 Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK 4 Alberta Geological Survey, 4th Floor Twin Atria Building, 4999-98 Ave. Edmonton, AB, T6B 2X3, Canada Correspondence to: Jean Vérité ([email protected]) Abstract. Conceptual ice stream landsystems derived from geomorphological and sedimentological observations provide 15 constraints on ice-meltwater-till-bedrock interactions on palaeo-ice stream beds. Within these landsystems, the spatial distribution and formation processes of ribbed bedforms remain unclear. We explore the conditions under which these bedforms develop and their spatial organisation with (i) an experimental model that reproduces the dynamics of ice streams and subglacial landsystems and (ii) an analysis of the distribution of ribbed bedforms on selected examples of paleo-ice stream beds of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. We find that a specific kind of ribbed bedforms can develop subglacially 20 from a flat bed beneath shear margins (i.e., lateral ribbed bedforms) and lobes (i.e., submarginal ribbed bedforms) of ice streams. -

Basal Control of Supraglacial Meltwater Catchments on the Greenland Ice Sheet

The Cryosphere, 12, 3383–3407, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-3383-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Basal control of supraglacial meltwater catchments on the Greenland Ice Sheet Josh Crozier1, Leif Karlstrom1, and Kang Yang2,3 1University of Oregon Department of Earth Sciences, Eugene, Oregon, USA 2School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China 3Joint Center for Global Change Studies, Beijing 100875, China Correspondence: Josh Crozier ([email protected]) Received: 5 April 2018 – Discussion started: 17 May 2018 Revised: 13 October 2018 – Accepted: 15 October 2018 – Published: 29 October 2018 Abstract. Ice surface topography controls the routing of sur- sliding regimes. Predicted changes to subglacial hydraulic face meltwater generated in the ablation zones of glaciers and flow pathways directly caused by changing ice surface to- ice sheets. Meltwater routing is a direct source of ice mass pography are subtle, but temporal changes in basal sliding or loss as well as a primary influence on subglacial hydrology ice thickness have potentially significant influences on IDC and basal sliding of the ice sheet. Although the processes spatial distribution. We suggest that changes to IDC size and that determine ice sheet topography at the largest scales are number density could affect subglacial hydrology primarily known, controls on the topographic features that influence by dispersing the englacial–subglacial input of surface melt- meltwater routing at supraglacial internally drained catch- water. ment (IDC) scales ( < 10s of km) are less well constrained. Here we examine the effects of two processes on ice sheet surface topography: transfer of bed topography to the surface of flowing ice and thermal–fluvial erosion by supraglacial 1 Introduction meltwater streams. -

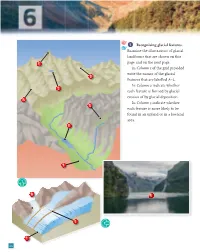

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Calving Processes and the Dynamics of Calving Glaciers ⁎ Douglas I

Earth-Science Reviews 82 (2007) 143–179 www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Calving processes and the dynamics of calving glaciers ⁎ Douglas I. Benn a,b, , Charles R. Warren a, Ruth H. Mottram a a School of Geography and Geosciences, University of St Andrews, KY16 9AL, UK b The University Centre in Svalbard, PO Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Norway Received 26 October 2006; accepted 13 February 2007 Available online 27 February 2007 Abstract Calving of icebergs is an important component of mass loss from the polar ice sheets and glaciers in many parts of the world. Calving rates can increase dramatically in response to increases in velocity and/or retreat of the glacier margin, with important implications for sea level change. Despite their importance, calving and related dynamic processes are poorly represented in the current generation of ice sheet models. This is largely because understanding the ‘calving problem’ involves several other long-standing problems in glaciology, combined with the difficulties and dangers of field data collection. In this paper, we systematically review different aspects of the calving problem, and outline a new framework for representing calving processes in ice sheet models. We define a hierarchy of calving processes, to distinguish those that exert a fundamental control on the position of the ice margin from more localised processes responsible for individual calving events. The first-order control on calving is the strain rate arising from spatial variations in velocity (particularly sliding speed), which determines the location and depth of surface crevasses. Superimposed on this first-order process are second-order processes that can further erode the ice margin. -

A General Theory of Glacier Surges

Journal of Glaciology A general theory of glacier surges D. I. Benn1, A. C. Fowler2,3, I. Hewitt2 and H. Sevestre1 1School of Geography and Sustainable Development, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, KY16 9AL, UK; 2Oxford Centre for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX2 6GG, UK and 3Mathematics Paper Applications Consortium for Science and Industry, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland Cite this article: Benn DI, Fowler AC, Hewitt I, Sevestre H (2019). A general theory of glacier Abstract surges. Journal of Glaciology 1–16. https:// We present the first general theory of glacier surging that includes both temperate and polythermal doi.org/10.1017/jog.2019.62 glacier surges, based on coupled mass and enthalpy budgets. Enthalpy (in the form of thermal Received: 19 February 2019 energy and water) is gained at the glacier bed from geothermal heating plus frictional heating Revised: 24 July 2019 (expenditure of potential energy) as a consequence of ice flow. Enthalpy losses occur by conduc- Accepted: 29 July 2019 tion and loss of meltwater from the system. Because enthalpy directly impacts flow speeds, mass and enthalpy budgets must simultaneously balance if a glacier is to maintain a steady flow. If not, Keywords: Dynamics; enthalpy balance theory; glacier glaciers undergo out-of-phase mass and enthalpy cycles, manifest as quiescent and surge phases. surge We illustrate the theory using a lumped element model, which parameterizes key thermodynamic and hydrological processes, including surface-to-bed drainage and distributed and channelized Author for correspondence: D. I. Benn, drainage systems. Model output exhibits many of the observed characteristics of polythermal E-mail: [email protected] and temperate glacier surges, including the association of surging behaviour with particular com- binations of climate (precipitation, temperature), geometry (length, slope) and bed properties (hydraulic conductivity). -

Generalized Sliding Law Applied to the Surge Dynamics of Shisper Glacier

https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2021-96 Preprint. Discussion started: 22 April 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Generalized sliding law applied to the surge dynamics of Shisper Glacier and constrained by timeseries correlation of optical satellite images Flavien Beaud1,2, Saif Aati1, Ian Delaney3,4, Surendra Adhikari3, and Jean-Philippe Avouac1 1Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 2Now at Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, CA 3Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 4Now at Institute of Earth Surface Dynamics, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland Correspondence: Flavien Beaud (fl[email protected]) Abstract. Understanding fast ice flow is key to assess the future of glaciers. Fast ice flow is controlled by sliding at the bed, yet that sliding is poorly understood. A growing number of studies show that the relationship between sliding and basal shear stress transitions from an initially rate-strengthening behavior to a rate-independent or rate-weakening behavior. Studies that have 5 tested a glacier sliding law with data remain rare. Surging glaciers, as we show in this study, can be used as a natural laboratory to inform sliding laws because a single glacier shows extreme velocity variations at a sub-annual timescale. The present study has two parts: (1) we introduce a new workflow to produce velocity maps with a high spatio-temporal resolution from remote sensing data combining Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 and use the results to describe the recent surge of Shisper glacier, and (2) we present a generalized sliding law and provide a first-order assessment of the sliding-law parameters using the remote sensing 10 dataset. -

Seismic Model Report.Pdf

Scientific Report GEFSC Loan 925 The Character and Extent of subglacial Deformation and its Links to Glacier Dynamics in the Tarfala Basin, northern Sweden Jeffrey Evans, David Graham, and Joseph Pomeroy Polar and Alpine Research Group, Loughborough University ABSTRACT A pilot passive seismology experiment was conducted across the main overdeepening of Storglaciaren in the Tarfala Basin, northern Sweden, in July 2010, to see whether basal microseismic waveforms could be detected beneath a small polythermal arctic glacier and to investigate the spatial and temporal distribution of such waveforms in relation to known glacier flow dynamics. The high ablation rate made it difficult to keep geophones buried and well- coupled to the glacier during the experiment and reduced the number of days of good quality data collection. Event counts and the subsequent characterisation of typical and atypical waveforms showed that the dominant waveforms detected were from near-surface events such as crevassing. Although basal sliding is known to occur in the overdeepening, no convincing examples of basal waveforms were detected, which suggests basal microseismic signals are rare or difficult to detect beneath polythermal glaciers like Storglaciaren, a finding that is consistent with results from alpine glaciers in Switzerland. The data- set could prove useful to glaciologists interested in the dynamics of near-surface events such as crevassing, the opening and closing of englacial water conduits, or temporal and spatial changes in the glacier’s stress field. Background Smith (2006) found that pervasive soft-bed deformation characterised parts of the Rutland Ice Stream in West Antarctica and produced 6 times fewer basal microseismic signals than regions where basal sliding or stick slip movement dominated. -

An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250

The Ohio Naturalist, PUBLISHED BY The Biological Club of the Ohio State University. Volume VIII. JANUARY. 1908. No. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS. SCHEPFEL—An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250 AN ESKER GROUP SOUTH OF DAYTON, OHIO.1 EARL R. SCHEFFEL Contents. Introduction. General Discussion of Eskers. Preliminary Description of Region. Bearing on Archaeology. Topographic Relations. Theories of Origin. Detailed Description of Eskers. Kame Area to the West of Eskers. Studies. Proximity of Eskers. Altitude of These Deposits. Height of Eskers. Composition of Eskers. Reticulation. Rock Weathering. Knolls. Crest-Lines. Economic Importance. Area to the East. Conclusion and Summary. Introduction. This paper has for its object the discussion of an esker group2 south of Dayton, Ohio;3 which group constitutes a part of the first or outer moraine of the Miami Lobe of the Late Wisconsin ice where it forms the east bluff of the Great Miami River south of Dayton.4 1. Given before the Ohio Academy of Science, Nov. 30, 1907, at Oxford, O., repre- senting work performed under the direction of Professor Frank Carney as partial requirement for the Master's Degree. 2. F: G. Clapp, Jour, of Geol., Vol. XII, (1904), pp. 203-210. 3. The writer's attention was first called to the group the past year under the name "Morainic Ridges," by Professor W. B. Werthner, of Steele High School, located in the city mentioned. Professor Werthner stated that Professor August P. Foerste of the same school and himself had spent some time together in the study of this region, but that the field was still clear for inves- tigation and publication. -

Multiple Glaciation and Gold-Placer

MULTIPLE GLACIATION AND GOLD-PLACER STATE OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL & GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS 1990 MULTIPLE GLACIATION AND GOLD-PLACER FORMATION, VALDEZ CREEK VALLEY, WESTERN CLEARWATER MOUNTAINS, ALASKA By Richard D. Reger and Thomas K. Bundtzen Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys Professional Report 107 Prepared in cooperation with U.S.Bureau of Mines Fairbanks, Alaska 1990 STATE OF ALASKA Steve Cowper, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Lennie Gorsuch, Commissioner DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL AND GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS Robert B. Forbes, Director and State Geologist Cover: Oblique aerial view northeast of Valdez Creek Mine and glaciated lower Valdez Creek valley. Photograph courtesy of Valdez Creek Mining Company. Available from Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys, 3700 Airport Way, Fairbanks, AK 997094699 and from U.S. Geological Sulvey Earth Science Information Centers, 4230 University Drive, Room 101, Anchorage, AK 99508 and 605 West 4th Avenue, Room G84, Anchorage, AK 99501. Mail orders should be addressed to the DGGS office in Fairbanks. Cost $4.50. CONTENTS I'age Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................ Introduction and mining history ................................................................................................................................ Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................................................... -

A Globally Complete Inventory of Glaciers

Journal of Glaciology, Vol. 60, No. 221, 2014 doi: 10.3189/2014JoG13J176 537 The Randolph Glacier Inventory: a globally complete inventory of glaciers W. Tad PFEFFER,1 Anthony A. ARENDT,2 Andrew BLISS,2 Tobias BOLCH,3,4 J. Graham COGLEY,5 Alex S. GARDNER,6 Jon-Ove HAGEN,7 Regine HOCK,2,8 Georg KASER,9 Christian KIENHOLZ,2 Evan S. MILES,10 Geir MOHOLDT,11 Nico MOÈ LG,3 Frank PAUL,3 Valentina RADICÂ ,12 Philipp RASTNER,3 Bruce H. RAUP,13 Justin RICH,2 Martin J. SHARP,14 THE RANDOLPH CONSORTIUM15 1Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA 2Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA 3Department of Geography, University of ZuÈrich, ZuÈrich, Switzerland 4Institute for Cartography, Technische UniversitaÈt Dresden, Dresden, Germany 5Department of Geography, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada E-mail: [email protected] 6Graduate School of Geography, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA 7Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway 8Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden 9Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria 10Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 11Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA 12Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada 13National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA 14Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 15A complete list of Consortium authors is in the Appendix ABSTRACT. The Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI) is a globally complete collection of digital outlines of glaciers, excluding the ice sheets, developed to meet the needs of the Fifth Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for estimates of past and future mass balance. -

Surficial Geology and Soils of the Elmira -Williamsport Region, New York and Pennsylvania

Surficial Geology and Soils of the Elmira -Williamsport Region, New York and Pennsylvania GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 379 Prepared cooperatively by the U.S. Department of the Interior^ Geological Survey and the U.S. De partment of Agriculture^ Soil Conservation Service Surficial Geology and Soils of the Elmira-Williamsport Region, New York and Pennsylvania By CHARLES S. DENNY, Geological Survey, and WALTER H. LYFORD, Soil Conservation Service With a section on FOREST REGIONS AND GREAT SOIL GROUPS By JOHN C. GOODLETT and WALTER H. LYFORD GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 379 Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey and the Soil Conservation Service UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1963 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C., 20402 CONTENTS Page Soils Continued Page Abstract--- ________________________________________ 1 Sols Bruns Acides, Gray-Brown Podzolic, and Red- Introduction_______________________________________ 2 Yellow Podzolic soils.._--_-_-__-__-___-_-__-__ 34 Acknowledgments-- _ ________________________________ 3 Weikert soil near Hughesville, Lycoming County, Topography. _______________________________________ 3 Pa______________________________________ 34 Bedrock geology.___________________________________ 4 Podzols and Sols Bruns Acides ____________________ 36 Surficial deposits of pre-Wisconsin age_________________ 4 Sols Bruns Acides and LowHumic-Gley soils._______ 37 Drift...__.____________________________________ 5 Chenango-Tunkhannock association. __________ 37 Colluvium and residuum_--_______-_--_-___-_____ 6 Chenango soil near Owego, Tioga County, Drift of Wisconsin age_-_-___________________________ 6 N.Y_________________________________ 37 Till. ________________________________________ 6 Lordstown-Bath-Mardin-Volusia association.... 39 Glaciofluvial deposits.___________________________ 7 Bath soil near Owego, Tioga County, N.Y.