Glaciers I: Intro, Geology and Mass Balance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basal Control of Supraglacial Meltwater Catchments on the Greenland Ice Sheet

The Cryosphere, 12, 3383–3407, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-3383-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Basal control of supraglacial meltwater catchments on the Greenland Ice Sheet Josh Crozier1, Leif Karlstrom1, and Kang Yang2,3 1University of Oregon Department of Earth Sciences, Eugene, Oregon, USA 2School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China 3Joint Center for Global Change Studies, Beijing 100875, China Correspondence: Josh Crozier ([email protected]) Received: 5 April 2018 – Discussion started: 17 May 2018 Revised: 13 October 2018 – Accepted: 15 October 2018 – Published: 29 October 2018 Abstract. Ice surface topography controls the routing of sur- sliding regimes. Predicted changes to subglacial hydraulic face meltwater generated in the ablation zones of glaciers and flow pathways directly caused by changing ice surface to- ice sheets. Meltwater routing is a direct source of ice mass pography are subtle, but temporal changes in basal sliding or loss as well as a primary influence on subglacial hydrology ice thickness have potentially significant influences on IDC and basal sliding of the ice sheet. Although the processes spatial distribution. We suggest that changes to IDC size and that determine ice sheet topography at the largest scales are number density could affect subglacial hydrology primarily known, controls on the topographic features that influence by dispersing the englacial–subglacial input of surface melt- meltwater routing at supraglacial internally drained catch- water. ment (IDC) scales ( < 10s of km) are less well constrained. Here we examine the effects of two processes on ice sheet surface topography: transfer of bed topography to the surface of flowing ice and thermal–fluvial erosion by supraglacial 1 Introduction meltwater streams. -

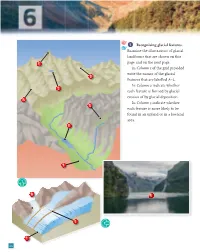

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Calving Processes and the Dynamics of Calving Glaciers ⁎ Douglas I

Earth-Science Reviews 82 (2007) 143–179 www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Calving processes and the dynamics of calving glaciers ⁎ Douglas I. Benn a,b, , Charles R. Warren a, Ruth H. Mottram a a School of Geography and Geosciences, University of St Andrews, KY16 9AL, UK b The University Centre in Svalbard, PO Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Norway Received 26 October 2006; accepted 13 February 2007 Available online 27 February 2007 Abstract Calving of icebergs is an important component of mass loss from the polar ice sheets and glaciers in many parts of the world. Calving rates can increase dramatically in response to increases in velocity and/or retreat of the glacier margin, with important implications for sea level change. Despite their importance, calving and related dynamic processes are poorly represented in the current generation of ice sheet models. This is largely because understanding the ‘calving problem’ involves several other long-standing problems in glaciology, combined with the difficulties and dangers of field data collection. In this paper, we systematically review different aspects of the calving problem, and outline a new framework for representing calving processes in ice sheet models. We define a hierarchy of calving processes, to distinguish those that exert a fundamental control on the position of the ice margin from more localised processes responsible for individual calving events. The first-order control on calving is the strain rate arising from spatial variations in velocity (particularly sliding speed), which determines the location and depth of surface crevasses. Superimposed on this first-order process are second-order processes that can further erode the ice margin. -

Seismic Model Report.Pdf

Scientific Report GEFSC Loan 925 The Character and Extent of subglacial Deformation and its Links to Glacier Dynamics in the Tarfala Basin, northern Sweden Jeffrey Evans, David Graham, and Joseph Pomeroy Polar and Alpine Research Group, Loughborough University ABSTRACT A pilot passive seismology experiment was conducted across the main overdeepening of Storglaciaren in the Tarfala Basin, northern Sweden, in July 2010, to see whether basal microseismic waveforms could be detected beneath a small polythermal arctic glacier and to investigate the spatial and temporal distribution of such waveforms in relation to known glacier flow dynamics. The high ablation rate made it difficult to keep geophones buried and well- coupled to the glacier during the experiment and reduced the number of days of good quality data collection. Event counts and the subsequent characterisation of typical and atypical waveforms showed that the dominant waveforms detected were from near-surface events such as crevassing. Although basal sliding is known to occur in the overdeepening, no convincing examples of basal waveforms were detected, which suggests basal microseismic signals are rare or difficult to detect beneath polythermal glaciers like Storglaciaren, a finding that is consistent with results from alpine glaciers in Switzerland. The data- set could prove useful to glaciologists interested in the dynamics of near-surface events such as crevassing, the opening and closing of englacial water conduits, or temporal and spatial changes in the glacier’s stress field. Background Smith (2006) found that pervasive soft-bed deformation characterised parts of the Rutland Ice Stream in West Antarctica and produced 6 times fewer basal microseismic signals than regions where basal sliding or stick slip movement dominated. -

What Glaciers Are Telling Us About Earth's Changing Climate

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | The Cryosphere Discuss., 8, 3475–3491, 2014 www.the-cryosphere-discuss.net/8/3475/2014/ doi:10.5194/tcd-8-3475-2014 TCD © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 8, 3475–3491, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal The Cryosphere (TC). What glaciers are Please refer to the corresponding final paper in TC if available. telling us about Earth’s changing What glaciers are telling us about Earth’s climate changing climate W. Tangborn and M. Mosteller W. Tangborn1 and M. Mosteller2 1HyMet Inc., Vashon Island, WA, USA Title Page 2 Vashon IT, Vashon Island, WA, USA Abstract Introduction Received: 12 June 2014 – Accepted: 24 June 2014 – Published: 1 July 2014 Conclusions References Correspondence to: W. Tangborn ([email protected]) and Tables Figures M. Mosteller ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. J I J I Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 3475 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract TCD A glacier monitoring system has been developed to systematically observe and docu- ment changes in the size and extent of a representative selection of the world’s 160 000 8, 3475–3491, 2014 mountain glaciers (entitled the PTAAGMB Project). Its purpose is to assess the impact 5 of climate change on human societies by applying an established relationship between What glaciers are glacier ablation and global temperatures. Two sub-systems were developed to accom- telling us about plish this goal: (1) a mass balance model that produces daily and annual glacier bal- Earth’s changing ances using routine meteorological observations, (2) a program that uses Google Maps climate to display satellite images of glaciers and the graphical results produced by the glacier 10 balance model. -

Surface Mass Balance of Davies Dome and Whisky Glacier on James Ross Island, North-Eastern Antarctic Peninsula, Based on Different Volume-Mass Conversion Approaches

CZECH POLAR REPORTS 9 (1): 1-12, 2019 Surface mass balance of Davies Dome and Whisky Glacier on James Ross Island, north-eastern Antarctic Peninsula, based on different volume-mass conversion approaches Zbyněk Engel1*, Filip Hrbáček2, Kamil Láska2, Daniel Nývlt2, Zdeněk Stachoň2 1Charles University, Faculty of Science, Department of Physical Geography and Geoecology, Albertov 6, 128 43 Praha, Czech Republic 2Masaryk University, Faculty of Science, Department of Geography, Kotlářská 2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic Abstract This study presents surface mass balance of two small glaciers on James Ross Island calculated using constant and zonally-variable conversion factors. The density of 500 and 900 kg·m–3 adopted for snow in the accumulation area and ice in the ablation area, respectively, provides lower mass balance values that better fit to the glaciological records from glaciers on Vega Island and South Shetland Islands. The difference be- tween the cumulative surface mass balance values based on constant (1.23 ± 0.44 m w.e.) and zonally-variable density (0.57 ± 0.67 m w.e.) is higher for Whisky Glacier where a total mass gain was observed over the period 2009–2015. The cumulative sur- face mass balance values are 0.46 ± 0.36 and 0.11 ± 0.37 m w.e. for Davies Dome, which experienced lower mass gain over the same period. The conversion approach does not affect much the spatial distribution of surface mass balance on glaciers, equilibrium line altitude and accumulation-area ratio. The pattern of the surface mass balance is almost identical in the ablation zone and very similar in the accumulation zone, where the constant conversion factor yields higher surface mass balance values. -

Trip F the PINNACLE HILLS and the MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A

F-1 Trip F THE PINNACLE HILLS AND THE MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A. Sanders Department of Geosciences Monroe Community College INTRODUCTION The Pinnacle Hills, fortunately, were voluminously described with many excellent photographs by Fairchild, (1923). In 1973 the Range still stands as a conspicuous east-west ridge extending from the town of Brighton, at about Hillside Avenue, four miles to the Genesee River at the University of Rochester campus, referred to as Oak Hill. But, for over thirty years the Range was butchered for sand and gravel, which was both a crime and blessing from the geological point of view (plates I-VI). First, it destroyed the original land form shapes which were subsequently covered with man-made structures drawing the shade on its original beauty. Secondly, it allowed study of its structure by a man with a brilliantly analytical mind, Herman L. Fair child. It is an excellent example of morainal deposition at an ice front in a state of dynamic equilibrium, except for minor fluctuations. The Mendon Kame area on the other hand, represents the result of a block of stagnant ice, probably detached and draped over drumlins and drumloidal hills, melting away with tunnels, crevasses, and per foration deposits spilling or squirting their included debris over a more or less square area leaving topographically high kames and esker F-2 segments with many kettles and a large central area of impounded drainage. There appears to be several wave-cut levels at around the + 700 1 Lake Dana level, (Fairchild, 1923). The author in no way pretends to be a Pleistocene expert, but an attempt is made to give a few possible interpretations of the many diverse forms found in the Mendon Kames area. -

Mass-Balance Reconstruction for Kahiltna Glacier, Alaska

Journal of Glaciology (2018), Page 1 of 14 doi: 10.1017/jog.2017.80 © The Author(s) 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The challenge of monitoring glaciers with extreme altitudinal range: mass-balance reconstruction for Kahiltna Glacier, Alaska JOANNA C. YOUNG,1 ANTHONY ARENDT,1,2 REGINE HOCK,1,3 ERIN PETTIT4 1Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK, USA 2Applied Physics Laboratory, Polar Science Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 3Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden 4Department of Geosciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA Correspondence: Joanna C. Young <[email protected]> ABSTRACT. Glaciers spanning large altitudinal ranges often experience different climatic regimes with elevation, creating challenges in acquiring mass-balance and climate observations that represent the entire glacier. We use mixed methods to reconstruct the 1991–2014 mass balance of the Kahiltna Glacier in Alaska, a large (503 km2) glacier with one of the greatest elevation ranges globally (264– 6108 m a.s.l.). We calibrate an enhanced temperature index model to glacier-wide mass balances from repeat laser altimetry and point observations, finding a mean net mass-balance rate of −0.74 − mw.e. a 1(±σ = 0.04, std dev. of the best-performing model simulations). Results are validated against mass changes from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites, a novel approach at the individual glacier scale. -

Crag-And-Tail Features on the Amundsen Sea Continental Shelf, West Antarctica

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on November 30, 2016 Crag-and-tail features on the Amundsen Sea continental shelf, West Antarctica F. O. NITSCHE1*, R. D. LARTER2, K. GOHL3, A. G. C. GRAHAM4 & G. KUHN3 1Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA 2British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 3Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Am Alten Hafen 26, D-27568 Bremerhaven, Germany 4College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Rennes Drive, Exeter EX4 4RJ, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) On parts of glaciated continental margins, especially the inner leads to its characteristic tapering and allows formation of the sec- shelves around Antarctica, grounded ice has removed pre-existing ondary features. Multiple, elongated ridges in the tail could be sedimentary cover, leaving subglacial bedforms on eroded sub- related to the unevenness of the top of the ‘crags’. Secondary, strates (Anderson et al. 2001; Wellner et al. 2001). While the smaller crag-and-tail features might reflect variations in the under- dominant subglacial bedforms often follow a distinct, relatively lying substrate or ice-flow dynamics. uniform pattern that can be related to overall trends in palaeo- While the length-to-width ratio of crag-and-tail features in this ice flow and substrate geology (Wellner et al. 2006), others are case is much lower than for drumlins or elongate lineations, the more randomly distributed and may reflect local substrate varia- boundary between feature classes is indistinct. -

COLD-BASED GLACIERS in the WESTERN DRY VALLEYS of ANTARCTICA: TERRESTRIAL LANDFORMS and MARTIAN ANALOGS: David R

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIV (2003) 1245.pdf COLD-BASED GLACIERS IN THE WESTERN DRY VALLEYS OF ANTARCTICA: TERRESTRIAL LANDFORMS AND MARTIAN ANALOGS: David R. Marchant1 and James W. Head2, 1Department of Earth Sciences, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215 [email protected], 2Department of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912 Introduction: Basal-ice and surface-ice temperatures are contacts and undisturbed underlying strata are hallmarks of cold- key parameters governing the style of glacial erosion and based glacier deposits [11]. deposition. Temperate glaciers contain basal ice at the pressure- Drop moraines: The term drop moraine is used here to melting point (wet-based) and commonly exhibit extensive areas describe debris ridges that form as supra- and englacial particles of surface melting. Such conditions foster basal plucking and are dropped passively at margins of cold-based glaciers (Fig. 1a abrasion, as well as deposition of thick matrix-supported drift and 1b). Commonly clast supported, the debris is angular and sheets, moraines, and glacio-fluvial outwash. Polar glaciers devoid of fine-grained sediment associated with glacial abrasion include those in which the basal ice remains below the pressure- [10, 12]. In the Dry Valleys, such moraines may be cored by melting point (cold-based) and, in extreme cases like those in glacier ice, owing to the insulating effect of the debris on the the western Dry Valleys region of Antarctica, lack surface underlying glacier. Where cored by ice, moraine crests can melting zones. These conditions inhibit significant glacial exceed the angle of repose. In plan view, drop moraines closely erosion and deposition. -

Inferred Basal Friction and Surface Mass Balance of the Northeast

The Cryosphere, 8, 2335–2351, 2014 www.the-cryosphere.net/8/2335/2014/ doi:10.5194/tc-8-2335-2014 © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Inferred basal friction and surface mass balance of the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream using data assimilation of ICESat (Ice Cloud and land Elevation Satellite) surface altimetry and ISSM (Ice Sheet System Model) E. Larour1, J. Utke3, B. Csatho4, A. Schenk4, H. Seroussi1, M. Morlighem2, E. Rignot1,2, N. Schlegel1, and A. Khazendar1 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory – California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive MS 300-323, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099, USA 2University of California Irvine, Department of Earth System Science, Croul Hall, Irvine, CA 92697-3100, USA 3Argonne National Lab, Argonne, IL 60439, USA 4Department of Geological Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA Correspondence to: E. Larour ([email protected]) Received: 5 April 2014 – Published in The Cryosphere Discuss.: 8 May 2014 Revised: 9 September 2014 – Accepted: 30 September 2014 – Published: 15 December 2014 Abstract. We present a new data assimilation method within 1 Introduction the Ice Sheet System Model (ISSM) framework that is capa- ble of assimilating surface altimetry data from missions such Global mean sea level (GMSL) rise observations show an as ICESat (Ice Cloud and land Elevation Satellite) into re- overall budget in which freshwater contribution from the po- constructions of transient ice flow. The new method relies on lar ice sheets represents a significant portion (Church and algorithmic differentiation to compute gradients of objective White, 2006, 2011; Stocker et al., 2013), which is actually functions with respect to model forcings. -

The Dynamics and Mass Budget of Aretic Glaciers

DA NM ARKS OG GRØN L ANDS GEO L OG I SKE UNDERSØGELSE RAP P ORT 2013/3 The Dynamics and Mass Budget of Aretic Glaciers Abstracts, IASC Network of Aretic Glaciology, 9 - 12 January 2012, Zieleniec (Poland) A. P. Ahlstrøm, C. Tijm-Reijmer & M. Sharp (eds) • GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF D EN MARK AND GREENLAND DANISH MINISTAV OF CLIMATE, ENEAGY AND BUILDING ~ G E U S DANMARKS OG GRØNLANDS GEOLOGISKE UNDERSØGELSE RAPPORT 201 3 / 3 The Dynamics and Mass Budget of Arctic Glaciers Abstracts, IASC Network of Arctic Glaciology, 9 - 12 January 2012, Zieleniec (Poland) A. P. Ahlstrøm, C. Tijm-Reijmer & M. Sharp (eds) GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF DENMARK AND GREENLAND DANISH MINISTRY OF CLIMATE, ENERGY AND BUILDING Indhold Preface 5 Programme 6 List of participants 11 Minutes from a special session on tidewater glaciers research in the Arctic 14 Abstracts 17 Seasonal and multi-year fluctuations of tidewater glaciers cliffson Southern Spitsbergen 18 Recent changes in elevation across the Devon Ice Cap, Canada 19 Estimation of iceberg to the Hansbukta (Southern Spitsbergen) based on time-lapse photos 20 Seasonal and interannual velocity variations of two outlet glaciers of Austfonna, Svalbard, inferred by continuous GPS measurements 21 Discharge from the Werenskiold Glacier catchment based upon measurements and surface ablation in summer 2011 22 The mass balance of Austfonna Ice Cap, 2004-2010 23 Overview on radon measurements in glacier meltwater 24 Permafrost distribution in coastal zone in Hornsund (Southern Spitsbergen) 25 Glacial environment of De Long Archipelago