Glacier Mass Balance This Summary Follows the Terminology Proposed by Cogley Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

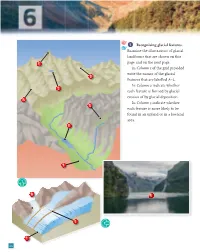

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Isotopic Oxygen-18 Results from Blue-Ice Areas

Isotopic oxygen-18 results Tongue blue-ice field ranges in 8180 from –40.7 to –58.8 parts per thousand. In a 200-meter transect with a sample every 10 from blue-ice areas meters, a 60-meter area of "yellow" or "dirty" ice has an av- erage 8180 value of –42.8 ± 1.4 parts per thousand, while the average for the blue-ice is –54.4 ± 0.3 parts per thousand. P.M. GROOTES and M. STUIVER Lighter 8110 values seem also to be associated with the me- teorite-carrying ice. Detailed sampling on five large sample Quaternary Isotope Laboratory blocks showed no signs of sample contamination and enrich- University of Washington ment. Seattle, Washington 98195 The observed i8O range is more than triple the glacial/in- terglacial 8180 change and the isotopically light ice, therefore, We measured the oxygen isotope abundance ratio oxygen - must have originated in the high interior of East Antarctica. 18/oxygen-16 in three sets of samples from blue-ice ablation The most negative value of –58.8 parts per thousand is, how- areas west of the Transantarctic Mountains. Samples were col- ever, still lighter than present snow accumulating at the Pole lected at the Reckling Moraine (by C. Faure), the Lewis Cliff of Relative Inaccessibility (-57 parts per thousand, Lorius 1983). Ice Tongue (by W.A. Cassidy, submitted by P. Englert), and If this ice had been formed during a glacial period, the source the Allan Hills (by J.O. Annexstad). Most samples were cut area could be closer to the Transantarctic Mountains. -

Calving Processes and the Dynamics of Calving Glaciers ⁎ Douglas I

Earth-Science Reviews 82 (2007) 143–179 www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Calving processes and the dynamics of calving glaciers ⁎ Douglas I. Benn a,b, , Charles R. Warren a, Ruth H. Mottram a a School of Geography and Geosciences, University of St Andrews, KY16 9AL, UK b The University Centre in Svalbard, PO Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Norway Received 26 October 2006; accepted 13 February 2007 Available online 27 February 2007 Abstract Calving of icebergs is an important component of mass loss from the polar ice sheets and glaciers in many parts of the world. Calving rates can increase dramatically in response to increases in velocity and/or retreat of the glacier margin, with important implications for sea level change. Despite their importance, calving and related dynamic processes are poorly represented in the current generation of ice sheet models. This is largely because understanding the ‘calving problem’ involves several other long-standing problems in glaciology, combined with the difficulties and dangers of field data collection. In this paper, we systematically review different aspects of the calving problem, and outline a new framework for representing calving processes in ice sheet models. We define a hierarchy of calving processes, to distinguish those that exert a fundamental control on the position of the ice margin from more localised processes responsible for individual calving events. The first-order control on calving is the strain rate arising from spatial variations in velocity (particularly sliding speed), which determines the location and depth of surface crevasses. Superimposed on this first-order process are second-order processes that can further erode the ice margin. -

What Glaciers Are Telling Us About Earth's Changing Climate

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | The Cryosphere Discuss., 8, 3475–3491, 2014 www.the-cryosphere-discuss.net/8/3475/2014/ doi:10.5194/tcd-8-3475-2014 TCD © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 8, 3475–3491, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal The Cryosphere (TC). What glaciers are Please refer to the corresponding final paper in TC if available. telling us about Earth’s changing What glaciers are telling us about Earth’s climate changing climate W. Tangborn and M. Mosteller W. Tangborn1 and M. Mosteller2 1HyMet Inc., Vashon Island, WA, USA Title Page 2 Vashon IT, Vashon Island, WA, USA Abstract Introduction Received: 12 June 2014 – Accepted: 24 June 2014 – Published: 1 July 2014 Conclusions References Correspondence to: W. Tangborn ([email protected]) and Tables Figures M. Mosteller ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. J I J I Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 3475 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract TCD A glacier monitoring system has been developed to systematically observe and docu- ment changes in the size and extent of a representative selection of the world’s 160 000 8, 3475–3491, 2014 mountain glaciers (entitled the PTAAGMB Project). Its purpose is to assess the impact 5 of climate change on human societies by applying an established relationship between What glaciers are glacier ablation and global temperatures. Two sub-systems were developed to accom- telling us about plish this goal: (1) a mass balance model that produces daily and annual glacier bal- Earth’s changing ances using routine meteorological observations, (2) a program that uses Google Maps climate to display satellite images of glaciers and the graphical results produced by the glacier 10 balance model. -

A Globally Complete Inventory of Glaciers

Journal of Glaciology, Vol. 60, No. 221, 2014 doi: 10.3189/2014JoG13J176 537 The Randolph Glacier Inventory: a globally complete inventory of glaciers W. Tad PFEFFER,1 Anthony A. ARENDT,2 Andrew BLISS,2 Tobias BOLCH,3,4 J. Graham COGLEY,5 Alex S. GARDNER,6 Jon-Ove HAGEN,7 Regine HOCK,2,8 Georg KASER,9 Christian KIENHOLZ,2 Evan S. MILES,10 Geir MOHOLDT,11 Nico MOÈ LG,3 Frank PAUL,3 Valentina RADICÂ ,12 Philipp RASTNER,3 Bruce H. RAUP,13 Justin RICH,2 Martin J. SHARP,14 THE RANDOLPH CONSORTIUM15 1Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA 2Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA 3Department of Geography, University of ZuÈrich, ZuÈrich, Switzerland 4Institute for Cartography, Technische UniversitaÈt Dresden, Dresden, Germany 5Department of Geography, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada E-mail: [email protected] 6Graduate School of Geography, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA 7Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway 8Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden 9Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria 10Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 11Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA 12Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada 13National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA 14Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 15A complete list of Consortium authors is in the Appendix ABSTRACT. The Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI) is a globally complete collection of digital outlines of glaciers, excluding the ice sheets, developed to meet the needs of the Fifth Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for estimates of past and future mass balance. -

Glaciers and Their Significance for the Earth Nature - Vladimir M

HYDROLOGICAL CYCLE – Vol. IV - Glaciers and Their Significance for the Earth Nature - Vladimir M. Kotlyakov GLACIERS AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE FOR THE EARTH NATURE Vladimir M. Kotlyakov Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Keywords: Chionosphere, cryosphere, glacial epochs, glacier, glacier-derived runoff, glacier oscillations, glacio-climatic indices, glaciology, glaciosphere, ice, ice formation zones, snow line, theory of glaciation Contents 1. Introduction 2. Development of glaciology 3. Ice as a natural substance 4. Snow and ice in the Nature system of the Earth 5. Snow line and glaciers 6. Regime of surface processes 7. Regime of internal processes 8. Runoff from glaciers 9. Potentialities for the glacier resource use 10. Interaction between glaciation and climate 11. Glacier oscillations 12. Past glaciation of the Earth Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Past, present and future of glaciation are a major focus of interest for glaciology, i.e. the science of the natural systems, whose properties and dynamics are determined by glacial ice. Glaciology is the science at the interfaces between geography, hydrology, geology, and geophysics. Not only glaciers and ice sheets are its subjects, but also are atmospheric ice, snow cover, ice of water basins and streams, underground ice and aufeises (naleds). Ice is a mono-mineral rock. Ten crystal ice variants and one amorphous variety of the ice are known.UNESCO Only the ice-1 variant has been – reve EOLSSaled in the Nature. A cryosphere is formed in the region of interaction between the atmosphere, hydrosphere and lithosphere, and it is characterized bySAMPLE negative or zero temperature. CHAPTERS Glaciology itself studies the glaciosphere that is a totality of snow-ice formations on the Earth's surface. -

Surface Mass Balance of Davies Dome and Whisky Glacier on James Ross Island, North-Eastern Antarctic Peninsula, Based on Different Volume-Mass Conversion Approaches

CZECH POLAR REPORTS 9 (1): 1-12, 2019 Surface mass balance of Davies Dome and Whisky Glacier on James Ross Island, north-eastern Antarctic Peninsula, based on different volume-mass conversion approaches Zbyněk Engel1*, Filip Hrbáček2, Kamil Láska2, Daniel Nývlt2, Zdeněk Stachoň2 1Charles University, Faculty of Science, Department of Physical Geography and Geoecology, Albertov 6, 128 43 Praha, Czech Republic 2Masaryk University, Faculty of Science, Department of Geography, Kotlářská 2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic Abstract This study presents surface mass balance of two small glaciers on James Ross Island calculated using constant and zonally-variable conversion factors. The density of 500 and 900 kg·m–3 adopted for snow in the accumulation area and ice in the ablation area, respectively, provides lower mass balance values that better fit to the glaciological records from glaciers on Vega Island and South Shetland Islands. The difference be- tween the cumulative surface mass balance values based on constant (1.23 ± 0.44 m w.e.) and zonally-variable density (0.57 ± 0.67 m w.e.) is higher for Whisky Glacier where a total mass gain was observed over the period 2009–2015. The cumulative sur- face mass balance values are 0.46 ± 0.36 and 0.11 ± 0.37 m w.e. for Davies Dome, which experienced lower mass gain over the same period. The conversion approach does not affect much the spatial distribution of surface mass balance on glaciers, equilibrium line altitude and accumulation-area ratio. The pattern of the surface mass balance is almost identical in the ablation zone and very similar in the accumulation zone, where the constant conversion factor yields higher surface mass balance values. -

Edges of Ice-Sheet Glaciology

Important Things Ice Sheets Do, but Ice Sheet Models Don’t Dr. Robert Bindschadler Chief Scientist Hydrospheric and Biospheric Sciences Laboratory NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [email protected] I’ll talk about • Why we need models – from a non-modeler • Why we need good models – recent observations have destroyed confidence in present models • Recent ice-sheet surprises • Responsible physical processes “…understanding of (possible future rapid dynamical changes in ice flow) is too limited to assess their likelihood or provide a best estimate or an upper bound for sea level rise.” IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, Summary for Policy Makers (2007) Future Sea Level is likely underestimated A1B IPCC AR4 (2007) Ice Sheets matter Globally Source: CReSIS and NASA Land area lost by 1-meter rise in sea level Impact of 1-meter sea level rise: Source: Anthoff et al., 2006 Maldives 20th Century Greenland Ice Sheet Sea level Change (mm/a) -1 0 +1 accumulation 450 Gt/a melting 225 Gt/a ice flow 225 Gt/a Approximately in “mass balance” 21st Century Greenland Ice Sheet Sea level Change (mm/a) -1 0 +1 accumulation melting ice flow Things could get a little better or a lot worse Increased ice flow will dominate the future rate of change A History Lesson • Less ice in HIGH SEA LEVEL Less warmer ice climates • Ice sheets More shrink faster LOW ice than they TEMPERATURE WARM grow • Sea level change is not COLD THEN NOW smooth Time Decreasing Mass Balance (Source: Luthcke et al., unpub.) Greenland Ice Sheet Mass Balance GREENLAND (Source: IPCC FAR) Antarctic Ice Sheet Mass Balance ANTARCTICA (Source: IPCC FAR) Pace of ice sheet changes have astonished experts is the common agent behind these changes Ice sheets HATE water! Fastest Flow at the Edges Interior: 1000’s meters thick and slow Perimeter: 100’s meters thick and fast Source: Rignot and Thomas Response time and speed of perturbation propagation are tied directly to ice flow speed 1. -

Ilulissat Icefjord

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1149.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Ilulissat Icefjord DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 7th July 2004 STATE PARTY: DENMARK CRITERIA: N (i) (iii) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (i): The Ilulissat Icefjord is an outstanding example of a stage in the Earth’s history: the last ice age of the Quaternary Period. The ice-stream is one of the fastest (19m per day) and most active in the world. Its annual calving of over 35 cu. km of ice accounts for 10% of the production of all Greenland calf ice, more than any other glacier outside Antarctica. The glacier has been the object of scientific attention for 250 years and, along with its relative ease of accessibility, has significantly added to the understanding of ice-cap glaciology, climate change and related geomorphic processes. Criterion (iii): The combination of a huge ice sheet and a fast moving glacial ice-stream calving into a fjord covered by icebergs is a phenomenon only seen in Greenland and Antarctica. Ilulissat offers both scientists and visitors easy access for close view of the calving glacier front as it cascades down from the ice sheet and into the ice-choked fjord. The wild and highly scenic combination of rock, ice and sea, along with the dramatic sounds produced by the moving ice, combine to present a memorable natural spectacle. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Located on the west coast of Greenland, 250-km north of the Arctic Circle, Greenland’s Ilulissat Icefjord (40,240-ha) is the sea mouth of Sermeq Kujalleq, one of the few glaciers through which the Greenland ice cap reaches the sea. -

Mass-Balance Reconstruction for Kahiltna Glacier, Alaska

Journal of Glaciology (2018), Page 1 of 14 doi: 10.1017/jog.2017.80 © The Author(s) 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The challenge of monitoring glaciers with extreme altitudinal range: mass-balance reconstruction for Kahiltna Glacier, Alaska JOANNA C. YOUNG,1 ANTHONY ARENDT,1,2 REGINE HOCK,1,3 ERIN PETTIT4 1Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK, USA 2Applied Physics Laboratory, Polar Science Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 3Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden 4Department of Geosciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA Correspondence: Joanna C. Young <[email protected]> ABSTRACT. Glaciers spanning large altitudinal ranges often experience different climatic regimes with elevation, creating challenges in acquiring mass-balance and climate observations that represent the entire glacier. We use mixed methods to reconstruct the 1991–2014 mass balance of the Kahiltna Glacier in Alaska, a large (503 km2) glacier with one of the greatest elevation ranges globally (264– 6108 m a.s.l.). We calibrate an enhanced temperature index model to glacier-wide mass balances from repeat laser altimetry and point observations, finding a mean net mass-balance rate of −0.74 − mw.e. a 1(±σ = 0.04, std dev. of the best-performing model simulations). Results are validated against mass changes from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites, a novel approach at the individual glacier scale. -

Glacier Lake, Saddle, & Blue Ice Trails

Guide to Glacier Lake, Saddle, & Blue Ice Trails in Kachemak Bay State Park Trail Access: Glacier Spit, Saddle, or Humpy Creek Grewingk Tram Spur (1 mile, easy) Allowable Uses: Hiking This spur connects Glacier Distance: 3.2 mi one-way (Glacier Lake Trail) Lake Trail and Emerald Lake Loop Trail. There is a hand- 1.0 mi one way (Saddle Trail) operated cable car pulley 6.7 mi one-way (Glacier Spit to Blue Ice Trail end) system over Grewingk Elevation Gain: 200 ft (Glacier Lake Trail) Creek. Operation requires 200 ft (Glacier Lake to Saddle Trailhead) two people. Maximum capacity of the tram is 500 500 ft (Glacier Spit to Blue Ice Trail end) pounds. If only two people are crossing the Difficulty: Easy; family suitable (Glacier Lake Trail) tram, one person should stay behind and assist in Camping: Moderate (Saddle Trail) pulling the other across. Two people in the tram cart without assistance from others on the plat- Glacier Spit, Grewingk Glacier Lake, Grewingk Creek, Moderate (Blue Ice Trail) form is difficult. Gloves are helpful in operating Tarn Lake, Humpy Creek, Right Beach (accessible at Hiking Time: 1.5 hours (to end Glacier Lake Trail) low tide from Glacier Spit) the tram. 30 minutes (Saddle Trail) Water Availability: 5 hours (Glacier Spit to Blue Ice Trail end) Glacier Lake & Saddle Trails: Grewingk Creek (glacial), Grewingk Glacier Lake A Popular route joins the Saddle and Glacier Lake (glacial), small streams near glacier and on Saddle Tr. Blue Ice Trail: Trails. The Glacier Lake Trail follows flat terrain Safety and Considerations: This is the only developed access to Grewingk through stands of cottonwoods & spruce, and CAUTION: Unless properly trained and outfitted for Glacier. -

Antarctic Surface and Subsurface Snow and Ice Melt Fluxes

15 MAY 2005 L I S T O N A N D W I N THER 1469 Antarctic Surface and Subsurface Snow and Ice Melt Fluxes GLEN E. LISTON Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado JAN-GUNNAR WINTHER Norwegian Polar Institute, Polar Environmental Centre, Tromsø, Norway (Manuscript received 19 April 2004, in final form 22 October 2004) ABSTRACT This paper presents modeled surface and subsurface melt fluxes across near-coastal Antarctica. Simula- tions were performed using a physical-based energy balance model developed in conjunction with detailed field measurements in a mixed snow and blue-ice area of Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica. The model was combined with a satellite-derived map of Antarctic snow and blue-ice areas, 10 yr (1991–2000) of Antarctic meteorological station data, and a high-resolution meteorological distribution model, to provide daily simulated melt values on a 1-km grid covering Antarctica. Model simulations showed that 11.8% and 21.6% of the Antarctic continent experienced surface and subsurface melt, respectively. In addition, the simula- tions produced 10-yr averaged subsurface meltwater production fluxes of 316.5 and 57.4 km3 yrϪ1 for snow-covered and blue-ice areas, respectively. The corresponding figures for surface melt were 46.0 and 2.0 km3 yrϪ1, respectively, thus demonstrating the dominant role of subsurface over surface meltwater pro- duction. In total, computed surface and subsurface meltwater production values equal 31 mm yrϪ1 if evenly distributed over all of Antarctica. While, at any given location, meltwater production rates were highest in blue-ice areas, total annual Antarctic meltwater production was highest for snow-covered areas due to its larger spatial extent.