GLACIERS and GLACIATION in GLACIER NATIONAL PARK by J Mines Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peaks-Glacier

Glacier National Park Summit List ©2003, 2006 Glacier Mountaineering Society Page 1 Summit El Quadrangle Notes ❑ Adair Ridge 5,366 Camas Ridge West ❑ Ahern Peak 8,749 Ahern Pass ❑ Allen Mountain 9,376 Many Glacier ❑ Almost-A-Dog Mtn. 8,922 Mount Stimson ❑ Altyn Peak 7,947 Many Glacier ❑ Amphitheater Mountain 8,690 Cut Bank Pass ❑ Anaconda Peak 8,279 Mount Geduhn ❑ Angel Wing 7,430 Many Glacier ❑ Apgar Mountains 6,651 McGee Meadow ❑ Apikuni Mountain 9,068 Many Glacier ❑ Appistoki Peak 8,164 Squaw Mountain ❑ B-7 Pillar (3) 8,712 Ahern Pass ❑ Bad Marriage Mtn. 8,350 Cut Bank Pass ❑ Baring Point 7,306 Rising Sun ❑ Barrier Buttes 7,402 Mount Rockwell ❑ Basin Mountain 6,920 Kiowa ❑ Battlement Mountain 8,830 Mount Saint Nicholas ❑ Bear Mountain 8,841 Mount Cleveland ❑ Bear Mountain Point 6,300 Gable Mountain ❑ Bearhat Mountain 8,684 Mount Cannon ❑ Bearhead Mountain 8,406 Squaw Mountain ❑ Belton Hills 6,339 Lake McDonald West ❑ Bighorn Peak 7,185 Vulture Peak ❑ Bishops Cap 9,127 Logan Pass ❑ Bison Mountain 7,833 Squaw Mountain ❑ Blackfoot Mountain 9,574 Mount Jackson ❑ Blacktail Hills 6,092 Blacktail ❑ Boulder Peak 8,528 Mount Carter ❑ Boulder Ridge 6,415 Lake Sherburne ❑ Brave Dog Mountain 8,446 Blacktail ❑ Brown, Mount 8,565 Mount Cannon ❑ Bullhead Point 7,445 Many Glacier ❑ Calf Robe Mountain 7,920 Squaw Mountain ❑ Campbell Mountain 8,245 Porcupine Ridge ❑ Cannon, Mount 8,952 Mount Cannon ❑ Cannon, Mount, SW Pk. 8,716 Mount Cannon ❑ Caper Peak 8,310 Mount Rockwell ❑ Carter, Mount 9,843 Mount Carter ❑ Cataract Mountain 8,180 Logan Pass ❑ Cathedral -

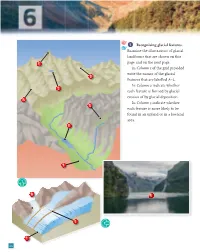

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Going-To-The-Sun Road Historic District, Glacier National Park

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2002 Going-to-the-Sun Road Historic District Glacier National Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Going-to-the-Sun Road Historic District Glacier National Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national -

Glacier NATIONAL PARK, MONTANA

Glacier NATIONAL PARK, MONTANA, UNITED STATES SECTION WATERTON-GLACIER INTERNATIONAL PEACE PARK Divide in northwestern Montana, contains nearly 1,600 ivy. We suggest that you pack your lunch, leave your without being burdened with camping equipment, you may square miles of some of the most spectacular scenery and automobile in a parking area, and spend a day or as much hike to either Sperry Chalets or Granite Park Chalets, primitive wilderness in the entire Rocky Mountain region. time as you can spare in the out of doors. Intimacy with where meals and overnight accommodations are available. Glacier From the park, streams flow northward to Hudson Bay, nature is one of the priceless experiences offered in this There are shelter cabins at Gunsight Lake and Gunsight eastward to the Gulf of Mexico, and westward to the Pa mountain sanctuary. Surely a hike into the wilderness will Pass, Fifty Mountain, and Stoney Indian Pass. The shelter cific. It is a land of sharp, precipitous peaks and sheer be the highlight of your visit to the park and will provide cabins are equipped with beds and cooking stoves, but you NATIONAL PARK knife-edged ridges, girdled with forests. Alpine glaciers you with many vivid memories. will have to bring your own sleeping and cooking gear. lie in the shadow of towering walls at the head of great ice- Trail trips range in length from short, 15-minute walks For back-country travel, you will need a topographic map carved valleys. along self-guiding nature trails to hikes that may extend that shows trails, streams, lakes, mountains, and glaciers. -

Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION

Form No. i0-306 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR lli|$|l;!tli:®pls NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES iliiiii: INVENTORY- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Glacier National Park NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT West Glacier X- VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Montana 30 Flathead 029 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT X.PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X.COMMERCIAL X_RARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT N/AN PR OCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY _OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (Happlicable) ______National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region STREET & NUMBER ____655 Parfet, P.O. Box 25287 CITY. TOWN STATE N/A _____Denver VICINITY OF Colorado 80225 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Qlacier National STREET & NUMBER N/A CITY. TOWN STATE West Glacier Montana REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE List of Classified Structures Inventory DATE August 1975 X-FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region CITY. TOWN STATE Colorado^ DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE X.GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory are situated near the Swiftcurrent Pass in Glacier National Park at an elevation of 7,000 feet. -

General Correspondence, July 10-25, 1923

• 10. 19 ] • • • - • d ,. out of ill o. ',. V ./ ( ) , t . • July r .... • ., .. / t 0 • '" niotor ' 'to t 0 'fill· oocumr , , 0 , ~ ~u 1 or ttL • t of us f"o t . e .. ey• , y • • • .. ablu, .. .. ull., / 0 C py • .. v 1:. I -u . 7- 1ti-P~ ~ I ~ -• J . - ., ; . '" / • ! , .. o thorn e , J ly ],9. 1923. • Ir. ' . • ey: • I J On uth rn ~ci· ne, cT- ly 18. 1923 • • -~ --- -.-----.---. I t e t Cel., July 20, 1 23. .1"' . c. lb"ty: . I tntt to' th !.llk or l~ . tl"oubl to n~G u.p for move- c .. t f c~ to co £0 00- , the tr ythi.. ~ - t £i c;it moon. - f crrivc he~.., t.e c:::rbcf i "1 d,,, in i. 1;1 oJ i rin~ to Inci<J I of . fa 'I 1 • to (}ate I min- of y ur at rTf '10 1I:r· ill you about it ·urn .. • pt..sa 0 n. I , ., . • • • • u1 • • o • • • GREAT ORTHERN RAILWAY COMPA EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT LOUIS W . HILL. CHAIRMAN OF THE BoARD (C 0 P y) -ST. PAUL. MINN .• At Pebble Beach, Cal., .July 21, 1923. Mr • .J . R. Eakin, Superintendent, Glacier National Park, Be 1 ton, Montana. Dear Mr . Eakin: After a few days' trip in Glacier Park, I feel 1'should write you very frankly my observations and impressions, I cannot help but be greatly interested in the development of the Park as we have a very large investment there - about $1 , 500 , 000 - in the hotels, camps, cost of roads, bridges, etc. The Logan Pass Trail is not as wide nor in as good con dition as when originally constructed. -

Agassiz Glacier Glacier National Park, MT

Agassiz Glacier Glacier National Park, MT W. C. Alden photo Greg Pederson photo 1913 courtesy of GNP archives 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Agassiz Glacier Glacier National Park, MT M. V. Walker photo Greg Pederson photo 1943 courtesy of GNP archives 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Blackfoot – Jackson Glacier Glacier National Park, MT E. C. Stebinger photo courtesy of GNP 1914 archives Lisa McKeon photo 2009 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Blackfoot and Jackson Glaciers Glacier National Park, MT 1911 EC Stebinger photo GNP Archives 2009 Lisa McKeon photo USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Boulder Glacier Glacier National Park, MT T. J. Hileman photo Jerry DeSanto photo 1932 courtesy of GNP archives 1988 K. Ross Toole Archives Mansfield Library, UM USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Boulder Glacier Glacier National Park, MT T. J. Hileman photo Greg Pederson photo 1932 courtesy of GNP archives 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Boulder Glacier Glacier National Park, MT Morton Elrod photo circa 1910 courtesy of GNP archives Fagre / Pederson photo 2007 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Chaney Glacier Glacier National Park, MT M.R. Campbell photo Blase Reardon photo 1911 USGS Photographic Library 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Chaney Glacier Glacier National Park, MT M.R. Campbell photo Blase Reardon photo 1911 USGS Photographic Library 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Grant Glacier Glacier National Park, MT Morton Elrod photo Karen Holzer photo 1902 courtesy of GNP Archives 1998 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Grinnell Glacier Glacier National Park, MT F. -

July Newsletter

1 Climb. Hike. Ski. Bike. Paddle. Dedicated to the Enjoyment and Promotion of Responsible Outdoor Adventure. Club Contacts ABOUT THE CLUB: Website: http://rockymountaineers.com Mission Statement: e-mail: [email protected] The Rocky Mountaineers is a non-profit Mailing Address: club dedicated to the enjoyment and The Rocky Mountaineers promotion of responsible outdoor PO Box 4262 Missoula MT 59806 adventures. President: Joshua Phillips Meetings and Presentations: [email protected] Meetings are held the second Wednesday, Vice-President: David Wright September through May, at 6:00 PM at [email protected] Pipestone Mountaineering. Each meeting Secretary: Julie Kahl is followed by a featured presentation or [email protected] speaker at 7:00 PM. Treasurer: Steve Niday [email protected] Activities: Hiking Webmaster: Alden Wright Backpacking [email protected] Alpine Climbing & Scrambling Peak Bagging Newsletter Editor: Forest Dean Backcountry Skiing [email protected] Winter Mountaineering Track Skiing The Mountain Ear is the club newsletter of The Rocky Snowshoeing Mountaineers and is published near the beginning of Snowboarding every month. Anyone wishing to contribute articles of Mountain Biking interest are welcomed and encouraged to do so- contact the editor. Rock Climbing Canoeing & Kayaking Membership application can be found at the end of the Rafting newsletter. Kids Trips Terracaching/Geocaching 2 The Rocky Mountaineers 5th Annual GLACIER CLASSIC ********* Friday, August 28 – Sunday, August 30 Rising Sun Campground, Glacier National Park We invite all members, guests, friends (anyone!) to join us for our 5th Annual Glacier Classic. This year we will base our activities out of the Rising Sun Campground on the north side of St. -

Glacier Mass Balance This Summary Follows the Terminology Proposed by Cogley Et Al

Summer school in Glaciology, McCarthy 5-15 June 2018 Regine Hock Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks Glacier Mass Balance This summary follows the terminology proposed by Cogley et al. (2011) 1. Introduction: Definitions and processes Definition: Mass balance is the change in the mass of a glacier, or part of the glacier, over a stated span of time: t . ΔM = ∫ Mdt t1 The term mass budget is a synonym. The span of time is often a year or a season. A seasonal mass balance is nearly always either a winter balance or a summer balance, although other kinds of seasons are appropriate in some climates, such as those of the tropics. The definition of “year” depends on the measurement method€ (see Chap. 4). The mass balance, b, is the sum of accumulation, c, and ablation, a (the ablation is defined here as negative). The symbol, b (for point balances) and B (for glacier-wide balances) has traditionally been used in studies of surface mass balance of valley glaciers. t . b = c + a = ∫ (c+ a)dt t1 Mass balance is often treated as a rate, b dot or B dot. Accumulation Definition: € 1. All processes that add to the mass of the glacier. 2. The mass gained by the operation of any of the processes of sense 1, expressed as a positive number. Components: • Snow fall (usually the most important). • Deposition of hoar (a layer of ice crystals, usually cup-shaped and facetted, formed by vapour transfer (sublimation followed by deposition) within dry snow beneath the snow surface), freezing rain, solid precipitation in forms other than snow (re-sublimation composes 5-10% of the accumulation on Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica). -

1934 the MOUNTAINEERS Incorpora.Ted T�E MOUNTAINEER VOLUME TWENTY-SEVEN Number One

THE MOUNTAINEER VOLUME TWENTY -SEVEN Nom1-0ae Deceml.er, 19.34 GOING TO GLACIER PUBLISHED BY THE MOUNTAIN�ER.S INCOaPOllATBD SEATTLI: WASHINGTON. _,. Copyright 1934 THE MOUNTAINEERS Incorpora.ted T�e MOUNTAINEER VOLUME TWENTY-SEVEN Number One December, 1934 GOING TO GLACIER 7 •Organized 1906 Incorporated 1913 EDITORIAL BOARD, 1934 Phyllis Young Katharine A. Anderson C. F. Todd Marjorie Gregg Arthur R. Winder Subscription Price, $2.00 a Year Annual (only) Seventy-five Cents Published by THE MOUNTAINEERS Incorporated Seattle, Washington Entered as second class matter, December 15, 1920, at the Postofflce at Seattle, Washington, under the Act of March 3, 1879. TABLE OF CONTENTS Greeting ........................................................................Henr y S. Han, Jr. North Face of Mount Rainier ................................................ Wolf Baiter 3 r Going to Glacier, Illustrated ............... -.................... .Har iet K. Walker 6 Members of the 1934 Summer Outing........................................................ 8 The Lake Chelan Region ............. .N. W. <J1·igg and Arthiir R. Winder 11 Map and Illustration The Climb of Foraker, Illitstrated.................................... <J. S. Houston 17 Ascent of Spire Peak ............................................... -.. .Kenneth Chapman 18 Paradise to White River Camp on Skis .......................... Otto P. Strizek 20 Glacier Recession Studies ................................................H. Strandberg 22 The Mounta,ineer Climbers................................................ -

Brief Communication: Collapse of 4 Mm3 of Ice from a Cirque Glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina

The Cryosphere, 13, 997–1004, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-13-997-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Brief communication: Collapse of 4 Mm3 of ice from a cirque glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina Daniel Falaschi1,2, Andreas Kääb3, Frank Paul4, Takeo Tadono5, Juan Antonio Rivera2, and Luis Eduardo Lenzano1,2 1Departamento de Geografía, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza, 5500, Argentina 2Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias Ambientales, Mendoza, 5500, Argentina 3Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, 0371, Norway 4Department of Geography, University of Zürich, Zürich, 8057, Switzerland 5Earth Observation research Center, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, 2-1-1, Sengen, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8505, Japan Correspondence: Daniel Falaschi ([email protected]) Received: 14 September 2018 – Discussion started: 4 October 2018 Revised: 15 February 2019 – Accepted: 11 March 2019 – Published: 26 March 2019 Abstract. Among glacier instabilities, collapses of large der of up to several 105 m3, with extraordinary event vol- parts of low-angle glaciers are a striking, exceptional phe- umes of up to several 106 m3. Yet the detachment of large nomenon. So far, merely the 2002 collapse of Kolka Glacier portions of low-angle glaciers is a much less frequent pro- in the Caucasus Mountains and the 2016 twin detachments of cess and has so far only been documented in detail for the the Aru glaciers in western Tibet have been well documented. 130 × 106 m3 avalanche released from the Kolka Glacier in Here we report on the previously unnoticed collapse of an the Russian Caucasus in 2002 (Evans et al., 2009), and the unnamed cirque glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina recent 68±2×106 and 83±2×106 m3 collapses of two ad- in March 2007. -

Glaciers and Glaciation in Glacier National Park

Glaciers and Glaciation in Glacier National Park ICE CAVE IN THE NOW NON-EXISTENT BOULDER GLACIER PHOTO 1932) Special Bulletin No. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION Price ^fc Cents GLACIERS AND GLACIATION In GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson MT. OBERLIN CIRQUE AND BIRD WOMAN FALLS SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION. INC. In cooperation with NATIONAL PARK SERVICE DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR PRINTED IN U. S. A. BY GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION 1948 Revised 1952 THE O'NEIL PRINTERS- KAUSPELL *rs»JLLAU' GLACIERS AND GLACIATION IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson Head, Department of Geology and Geography Lafayette College Member, Research Committee on Glaciers American Geophysical Union* The glaciers of Glacier National Park are only a few of many thousands which occur in mountain ranges scattered throughout the world. Glaciers occur in all latitudes and on every continent except Australia. They are present along the Equator on high volcanic peaks of Africa and in the rugged Andes of South America. Even in New Guinea, which manj- veterans of World War II know as a steaming, tropical jungle island, a few small glaciers occur on the highest mountains. Almost everyone who has made a trip to a high mountain range has heard the term, "snowline,"' and many persons have used the word with out knowing its real meaning. The true snowline, or "regional snowline"' as the geologists call it, is the level above which more snow falls in winter than can be melted or evaporated during the summer. On mountains which rise above the snowline glaciers usually occur.