Brief Communication: Collapse of 4 Mm3 of Ice from a Cirque Glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Topography Increasingly Influences the Mass Balance of A

Local topography increasingly influences the mass balance of a retreating cirque glacier Caitlyn Florentine1, 2, Joel Harper2, Daniel Fagre1, Johnnie Moore2, Erich Peitzsch1 1U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, West Glacier, Montana, 59936, USA 5 2Department of Geosciences, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 59801, USA Correspondence to: Caitlyn Florentine ([email protected]) Abstract. Local topographically driven processes, such as wind drifting, avalanching, and shading, are known to alter the relationship between the mass balance of small cirque glaciers and regional climate. Yet partitioning such local effects from regional climate influence has proven difficult, creating uncertainty in the climate representativeness of some glaciers. We 10 address this problem for Sperry Glacier in Glacier National Park, USA using field-measured surface mass balance, geodetic constraints on mass balance, and regional climate data recorded at a network of meteorological and snow stations. Geodetically derived mass changes between 1950-1960, 1960-2005, and 2005-2014 document average mass change rates during each period at -0.22±0.12 m w.e. yr-1, -0.18±0.05 m w.e. yr-1, and -0.10±0.03 m w.e. yr-1. A correlation of field- measured mass balance and regional climate variables closely (i.e. within 0.08 m w.e. yr-1) predicts the geodetically 15 measured mass loss from 2005-2014. However, this correlation overestimates glacier mass balance for 1950-1960 by +1.18±0.92 m w.e. yr-1. Our analysis suggests that local effects, not represented in regional climate variables, have become a more dominant driver of the net mass balance as the glacier lost 0.50 km2 and retreated further into its cirque. -

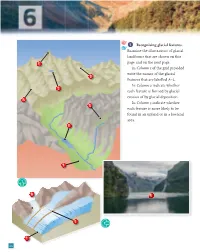

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Characteristics of the Bergschrund of an Avalanche-Cone Glacier in the Canadian Rocky Mountains

JOlIl"lla/ o/G/aci%gl'. VoL 29. No. 10 1. 1983 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BERGSCHRUND OF AN AVALANCHE-CONE GLACIER IN THE CANADIAN ROCKY MOUNTAINS By G ERALD OSBORN (Department of Geology and Geophysics, Uni versity o f Calgary, Calgary, Alberta T2N I N4, Canada) ABSTRACT. Fi eld study of th e bergschrund of a small avalanche-cone glacier at the base of Mt Chephren, in Banff Nati onal Park , has been ca rried out as part of a general ex pl oratory study of glacier-head crevasses in th e Canadi an Roc ki es. The bergsc hrun d consists of a wide. shall ow. partl y bedrock-fl oored gap, und erneath whi ch ex tends a nearl y vertical Ralldklu!I, and a small , offset, subsidi ary crevasse (or crevasses). The fo ll owin g observations rega rdin g the behavior of th e bergsc hruncl and ice adjacent to it are of parti cul ar interest: ( I) topograph y of the subglaeial bedrock is a control on the location of the main bergschrund and subsidi a ry crevasses. (2) th e main bergschrund and subsid ia ry crevasse(s) are conn ected by subglacial gaps betwee n bedrock and ice; th e gaps are part of th e "bergschrund system" , (3) snow/ ice immedi ately down-glacier of the bergschrund system moves nea rl y verticall y dow nwa rd in response to rotational fl ow of the glacier. a ll owin g the bergschrund components to keep the same location and size fro m year to year, (4) an inde pend ent accumul ati on, fl ow. -

Geomorphic Character, Age and Distribution of Rock Glaciers in the Olympic Mountains, Washington

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1987 Geomorphic character, age and distribution of rock glaciers in the Olympic Mountains, Washington Steven Paul Welter Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geology Commons, and the Geomorphology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Welter, Steven Paul, "Geomorphic character, age and distribution of rock glaciers in the Olympic Mountains, Washington" (1987). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3558. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5440 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Steven Paul Welter for the Master of Science in Geography presented August 7, 1987. Title: The Geomorphic Character, Age, and Distribution of Rock Glaciers in the Olympic Mountains, Washington APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Rock glaciers are tongue-shaped or lobate masses of rock debris which occur below cliffs and talus in many alpine regions. They are best developed in continental alpine climates where it is cold enough to preserve a core or matrix of ice within the rock mass but insufficiently snowy to produce true glaciers. Previous reports have identified and briefly described several rock glaciers in the Olympic Mountains, Washington {Long 1975a, pp. 39-41; Nebert 1984), but no detailed integrative study has been made regarding the geomorphic character, age, 2 and distribution of these features. -

Geology of Hyder and Vicinity Southeastern Alaska

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Roy O. West, Secretary U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY George Otis Smith, Director Bulletin 807 GEOLOGY OF HYDER AND VICINITY SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA WITH A RECONNAISSANCE OF CHICKAMIN RIVER BY A. F. RUDDINGTON UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1&29 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS TJ.S.OOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 35 CENTS PER COPY CONTENTS Page Foreword, by Philip S. Smith._________________________ vn Introduction...____________________________________________________ 1 Field work_.._.___._.______..____...____. -_-__-. .. 1 Acknowledgments. _-_-________-_-___-___-__--_____-__-- -____-_ 2 History._________________________________________________________ 2 Bibliography ________-______ _____________._-__.-___-__--__--_--_-_ 3 Alaska.__-___-__---______-_-____-_-___--____-___-_-___-__-___ & British Columbia____-_____-___-___________-_-___--___.._____- 4 Geography_______________________________________-____--___-__--_ 4 Location and transportation facilities.___________________________ 4 Climate. __--______-______.____--__---____-_______--._--.--__- 5 Vegetation ___________________________________________________ 6 Water power._--___._____.________.______-_.._____-___.-_____ 7 Topography-___________--____-_-___--____.___-___-----__--_-- 7 General features of the relief----______-_---___-__------_-_-_ 7 Streams.._ _______________________________________________ 9 Glaciation.. _ __-_____-__--__--_____-__---_____-__--_----__ 10 Geology.... __----_-._ -._---_--__-.- _-_____-_____-___-_ 13 General features___-_-____-__-__-___-..____--___-_-____--__-._ 13 Hazelton group._....._.._>___-_-.__-______----_-----'_-__-..-- 17 General character.-----.-------.-------------------------- 17 Greenstone and associated rocks.._______.__.-.--__--_--_--_ 18 Graywacke-slate division.._________-_-__--_-_-----_--_----_ 19 Coast.Range intrusives__________-__-__--___-----------_-----_- 22 Texas Creek batholith and associated dikes..__--__.__-__-__-. -

Glaciation and Hydrogeology Workshop Proceedings

SKI Report 97:13 SE9700378 Glaciation and Hydrogeology Workshop on the Impact of Climate Change & Glaciations on Rock stresses, Groundwater flow and Hydrochemistry - Past, Present and Future Workshop Proceedings Edited by: Louisa King-Clayton Neil Chapman Lars O Ericsson Fritz Kautsky April 1997 ISSN 1104-1374 ISRNSKI-R--97/13--SE STATENS KARNKRAFTINSPEKTION Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Swedish Nuclear Power Inspectorate Waste Management Co ML 9 ft fe 2 4 SKI Report 97:13 Glaciation and Hydrogeology Workshop on the Impact of Climate Change & Glaciations on Rock stresses, Groundwater flow and Hydrochemistry - Past, Present and Future Organised by: Nordic Nuclear Safety Research (NKS) Funding Organisations: The Swedish Nuclear Power Inspectorate (SKI) and the Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co (SKB) Scientific Secretariat: QuantiSci Ltd, UK Venue: Hasselby Castle Conference Centre, Stockholm, Sweden Date: 17-19 April 1996 Workshop Proceedings April 1997 Edited by: Louisa King-Clayton & Neil Chapman, QuantiSci Ltd, UK Lars O Ericsson, SKB, Sweden Fritz Kautsky, SKI, Sweden NORSTEDTS TRYCKERI AB Stockholm 1997 Workshop on the Impact of Climate Change & Glaciations on Rock Stresses, Groundwater flow and Hydrochemistry, Stockholm 1996 Contents Executive summary 2 Preface 4 1 Introduction 5 2 Workshop Structure 6 3 Background to Workshop Discussions (Day 1) 9 4 Climate Change and Quaternary Geology 23 5 Hydrogeological Aspects of Glaciation 33 6 Hydrogeochemical Aspects of Glaciation 45 7 Tectonic Aspects of Glaciation 52 8 Final Workshop -

An Investigation of the Thermo-Mechanical Features of Laohugou Glacier No.12 in Mt

An investigation of the thermo-mechanical features of Laohugou Glacier No.12 in Mt. Qilian Shan, western China, using a two-dimensional first-order flowband ice flow model Yuzhe Wang1,2, Tong Zhang3,a, Jiawen Ren1, Xiang Qin1, Yushuo Liu1, Weijun Sun4, Jizu Chen1,2, Minghu Ding3, Wentao Du1,2, and Dahe Qin1 1State Key Laboratory of Cryospheric Science, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, China 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3Insititute of Polar Meteorology, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing 100081, China 4College of Geography and Environment, Shandong Normal University, Jinan 250014, China anow at: Fluid Dynamics and Solid Mechanics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, New Mexico, 87545, USA Correspondence to: Tong Zhang ([email protected]) Abstract. By combining in situ measurements and a two-dimensional thermo-mechanically coupled ice flow model, we in- vestigate the thermo-mechanical features of the largest valley glacier (Laohugou Glacier No.12; LHG12) in Mt. Qilian Shan located in the arid region of western China. Our model results suggest that LHG12, previously considered as fully cold, is probably polythermal, with a lower temperate ice layer overlain by an upper layer of cold ice over a large region of the ablation 5 area. Modeled ice surface velocities match well with the in situ observations in the east branch (mainstreammain::::::::::branch) but clearly underestimate the ice surface velocities those:::: near the glacier terminus possibly because the convergent flow is ignored and the basal sliding beneath the confluence area is underestimated. The modeled ice temperatures are in very good agreement with the in situ measurements from a deep borehole (110 m deep::::) in the upper ablation area. -

Glacier Mass Balance This Summary Follows the Terminology Proposed by Cogley Et Al

Summer school in Glaciology, McCarthy 5-15 June 2018 Regine Hock Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks Glacier Mass Balance This summary follows the terminology proposed by Cogley et al. (2011) 1. Introduction: Definitions and processes Definition: Mass balance is the change in the mass of a glacier, or part of the glacier, over a stated span of time: t . ΔM = ∫ Mdt t1 The term mass budget is a synonym. The span of time is often a year or a season. A seasonal mass balance is nearly always either a winter balance or a summer balance, although other kinds of seasons are appropriate in some climates, such as those of the tropics. The definition of “year” depends on the measurement method€ (see Chap. 4). The mass balance, b, is the sum of accumulation, c, and ablation, a (the ablation is defined here as negative). The symbol, b (for point balances) and B (for glacier-wide balances) has traditionally been used in studies of surface mass balance of valley glaciers. t . b = c + a = ∫ (c+ a)dt t1 Mass balance is often treated as a rate, b dot or B dot. Accumulation Definition: € 1. All processes that add to the mass of the glacier. 2. The mass gained by the operation of any of the processes of sense 1, expressed as a positive number. Components: • Snow fall (usually the most important). • Deposition of hoar (a layer of ice crystals, usually cup-shaped and facetted, formed by vapour transfer (sublimation followed by deposition) within dry snow beneath the snow surface), freezing rain, solid precipitation in forms other than snow (re-sublimation composes 5-10% of the accumulation on Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica). -

GLACIERS and GLACIATION in GLACIER NATIONAL PARK by J Mines Ii

Glaciers and Glacial ion in Glacier National Park Price 25 Cents PUBLISHED BY THE GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Cover Surveying Sperry Glacier — - Arthur Johnson of U. S. G. S. N. P. S. Photo by J. W. Corson REPRINTED 1962 7.5 M PRINTED IN U. S. A. THE O'NEIL PRINTERS ^i/TsffKpc, KALISPELL, MONTANA GLACIERS AND GLACIATTON In GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson MT. OBERLIN CIRQUE AND BIRD WOMAN FALLS SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION. INC. GLACIERS AND GLACIATION IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By J Mines Ii. Dyson Head, Department of Geology and Geography Lafayette College Member, Research Committee on Glaciers American Geophysical Union* The glaciers of Glacier National Park are only a few of many thousands which occur in mountain ranges scattered throughout the world. Glaciers occur in all latitudes and on every continent except Australia. They are present along the Equator on high volcanic peaks of Africa and in the rugged Andes of South America. Even in New Guinea, which many think of as a steaming, tropical jungle island, a few small glaciers occur on the highest mountains. Almost everyone who has made a trip to a high mountain range has heard the term, "snowline," and many persons have used the word with out knowing its real meaning. The true snowline, or "regional snowline" as the geologists call it, is the level above which more snow falls in winter than can he melted or evaporated during the summer. On mountains which rise above the snowline glaciers usually occur. -

The Physical Geography of the Illinois River Valley Near Peoria

The Physical Geography of the Illinois River Valley Near Peoria An Updated Self-Conducted Field Trip using EcoCaches and GPS Technology Donald E. Bevenour East Peoria Community High School Illinois State University Copyright, 1991 Updated by: Kevin M. Emmons Morton High School Bradley University 2007 Additional Support: Martin Hobbs East Peoria Community High School Abstract THE PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE ILLINOIS RIVER VALLEY NEAR PEORIA: AN UPDATED SELF CONDUCTED FIELD TRIP USING ECOCACHES AND GPS TECHNOLOGY This field trip has been written so that anyone can enjoy the trip without the guidance of a professional. The trip could be taken by student groups, families, or an individual; at least two people, a driver and a reader/navigator, are the recommended minimum number of persons for maximum effectiveness and safety. Subjects of discussion include the Illinois River, the Bloomington, Shelbyville, and LeRoy Moraines, various aspects of the glacial history of the area, stream processes, floodplains, natural vegetation, and human adaptations to the physical environment such as agriculture, industry, transportation, and growth of cities. Activities include riding to the top of a lookout tower, judging distance to several landmark objects, and scenic views of the physical and cultural environment. All along the trip, GPS coordinates are supplied to aid you in your navigation. Information on EcoCaches is available at http://www.ilega.org/ Why take a self-guided field trip? A self-guided field trip is an excellent way to learn more about the area in which one lives. Newcomers or visitors to an area should find it a most enlightening manner in which to personalize the new territory. -

Cirques Have Growth Spurts During Deglacial and Interglacial Periods: Evidence from 10Be and 26Al Nuclide Inventories in the Central and Eastern Pyrenees Y

Cirques have growth spurts during deglacial and interglacial periods: Evidence from 10Be and 26Al nuclide inventories in the central and eastern Pyrenees Y. Crest, M Delmas, Regis Braucher, Y. Gunnell, M Calvet, A.S.T.E.R. Team To cite this version: Y. Crest, M Delmas, Regis Braucher, Y. Gunnell, M Calvet, et al.. Cirques have growth spurts during deglacial and interglacial periods: Evidence from 10Be and 26Al nuclide inventories in the central and eastern Pyrenees. Geomorphology, Elsevier, 2017, 278, pp.60 - 77. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.10.035. hal-01420871 HAL Id: hal-01420871 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01420871 Submitted on 21 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Geomorphology 278 (2017) 60–77 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Cirques have growth spurts during deglacial and interglacial periods: Evidence from 10Be and 26Al nuclide inventories in the central and eastern Pyrenees Y. Crest a,⁎,M.Delmasa,R.Braucherb, Y. Gunnell c,M.Calveta, ASTER Team b,1: a Univ Perpignan Via-Domitia, UMR 7194 CNRS Histoire Naturelle de l'Homme Préhistorique, 66860 Perpignan Cedex, France b Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS–IRD–Collège de France, UMR 34 CEREGE, Technopôle de l'Environnement Arbois–Méditerranée, BP80, 13545 Aix-en-Provence, France c Univ Lyon Lumière, Department of Geography, UMR 5600 CNRS Environnement Ville Société, 5 avenue Pierre Mendès-France, F-69676 Bron, France article info abstract Article history: Cirques are emblematic landforms of alpine landscapes. -

Cirques As Glacier Locations William L

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Geography, Department of 1976 Cirques as Glacier Locations William L. Graf [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/geog_facpub Part of the Geography Commons Publication Info Arctic and Alpine Research, Volume 8, Issue 1, 1976, pages 79-90. This Article is brought to you by the Geography, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arctic and Alpine Research, Vol. 8, No.1, 1976, pp. 79-90 Copyrighted 1976. All rights reserved. CIRQUES AS GLACIER LOCATIONS WILLIAM L. GRAF Department of Geography University of Iowa Iowa City, Iowa 52242 ABSTRACT A comparison between the 319 cirques that width greater than length, high steep walls, a contain glaciers and a sample of 240 empty pass located to the windward, and a peak to the cirques in the Rocky Mountains shows that in the southwest. Glaciers survive in the present cli present climatic situation, landforms are strong matic conditions because of a geomorphic feed factors in determining the locations of glaciers. back system, whereby glaciers are protected by An optimum glacier location is a large cirque cirque forms that owe their morphology to gla facing northeast, with a planimetric shape of cial processes. INTRODUCTION During the Pleistocene period, huge valley were recognized as products of glacial activity. and plateau glaciers covered large portions of The activities of cirque glaciers in developing the American Rocky Mountains, but as climate cirque morphology have been explored (Lewis, changed, glaciers receded and in most cases 1938) but, with one notable exception, the pro vanished.