Glacial Landsystems and Dynamics of the Saginaw Lobe of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, Michigan, USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Summary of Petroleum Plays and Characteristics of the Michigan Basin

DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A summary of petroleum plays and characteristics of the Michigan basin by Ronald R. Charpentier Open-File Report 87-450R This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Denver, Colorado 80225 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT.................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION.............................................. 3 REGIONAL GEOLOGY.......................................... 3 SOURCE ROCKS.............................................. 6 THERMAL MATURITY.......................................... 11 PETROLEUM PRODUCTION...................................... 11 PLAY DESCRIPTIONS......................................... 18 Mississippian-Pennsylvanian gas play................. 18 Antrim Shale play.................................... 18 Devonian anticlinal play............................. 21 Niagaran reef play................................... 21 Trenton-Black River play............................. 23 Prairie du Chien play................................ 25 Cambrian play........................................ 29 Precambrian rift play................................ 29 REFERENCES................................................ 32 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. Index map of Michigan basin province (modified from Ells, 1971, reprinted by permission of American Association of Petroleum Geologists)................. 4 2. Structure contour map on top of Precambrian basement, Lower Peninsula -

What Climate Change Means for Michigan

August 2016 EPA 430-F-16-024 What Climate Change Means for Michigan Michigan’s climate is changing. Most of the state has Heavy Precipitation and Flooding warmed two to three degrees (F) in the last century. Changing the climate is likely to increase the frequency of floods in Heavy rainstorms are becoming more frequent, and Michigan. Over the last half century, average annual precipitation in ice cover on the Great Lakes is forming later or melting most of the Midwest has increased by 5 to 10 percent. But rainfall sooner. In the coming decades, the state will have during the four wettest days of the year has increased about 35 more extremely hot days, which may harm public percent. During the next century, spring rainfall and annual precipitation health in urban areas and corn harvests in rural areas. are likely to increase, and severe rainstorms are likely to intensify. Each Our climate is changing because the earth is warming. of these factors will tend to further increase the risk of flooding. People have increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the air by 40 percent since the late 1700s. Other heat-trapping greenhouse gases are also increasing. These gases have warmed the surface and lower atmosphere of our planet about one degree during the last 50 years. Evaporation increases as the atmo- sphere warms, which increases humidity, average rainfall, and the frequency of heavy rainstorms in many places—but contributes to drought in others. Heavy rains and snowmelt flooded the Tittabawassee River in Midland in April Greenhouse gases are also changing the world’s 2015. -

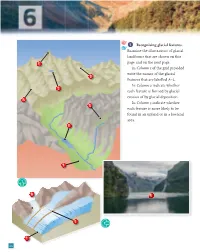

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Introduction to Geological Process in Illinois Glacial

INTRODUCTION TO GEOLOGICAL PROCESS IN ILLINOIS GLACIAL PROCESSES AND LANDSCAPES GLACIERS A glacier is a flowing mass of ice. This simple definition covers many possibilities. Glaciers are large, but they can range in size from continent covering (like that occupying Antarctica) to barely covering the head of a mountain valley (like those found in the Grand Tetons and Glacier National Park). No glaciers are found in Illinois; however, they had a profound effect shaping our landscape. More on glaciers: http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/10ad.html Formation and Movement of Glacial Ice When placed under the appropriate conditions of pressure and temperature, ice will flow. In a glacier, this occurs when the ice is at least 20-50 meters (60 to 150 feet) thick. The buildup results from the accumulation of snow over the course of many years and requires that at least some of each winter’s snowfall does not melt over the following summer. The portion of the glacier where there is a net accumulation of ice and snow from year to year is called the zone of accumulation. The normal rate of glacial movement is a few feet per day, although some glaciers can surge at tens of feet per day. The ice moves by flowing and basal slip. Flow occurs through “plastic deformation” in which the solid ice deforms without melting or breaking. Plastic deformation is much like the slow flow of Silly Putty and can only occur when the ice is under pressure from above. The accumulation of meltwater underneath the glacier can act as a lubricant which allows the ice to slide on its base. -

Indiana Glaciers.PM6

How the Ice Age Shaped Indiana Jerry Wilson Published by Wilstar Media, www.wilstar.com Indianapolis, Indiana 1 Previiously published as The Topography of Indiana: Ice Age Legacy, © 1988 by Jerry Wilson. Second Edition Copyright © 2008 by Jerry Wilson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2 For Aaron and Shana and In Memory of Donna 3 Introduction During the time that I have been a science teacher I have tried to enlist in my students the desire to understand and the ability to reason. Logical reasoning is the surest way to overcome the unknown. The best aid to reasoning effectively is having the knowledge and an understanding of the things that have previ- ously been determined or discovered by others. Having an understanding of the reasons things are the way they are and how they got that way can help an individual to utilize his or her resources more effectively. I want my students to realize that changes that have taken place on the earth in the past have had an effect on them. Why are some towns in Indiana subject to flooding, whereas others are not? Why are cemeteries built on old beach fronts in Northwest Indiana? Why would it be easier to dig a basement in Valparaiso than in Bloomington? These things are a direct result of the glaciers that advanced southward over Indiana during the last Ice Age. The history of the land upon which we live is fascinating. Why are there large granite boulders nested in some of the fields of northern Indiana since Indiana has no granite bedrock? They are known as glacial erratics, or dropstones, and were formed in Canada or the upper Midwest hundreds of millions of years ago. -

Quarrernary GEOLOGY of MINNESOTA and PARTS of ADJACENT STATES

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Ray Lyman ,Wilbur, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director P~ofessional Paper 161 . QUArrERNARY GEOLOGY OF MINNESOTA AND PARTS OF ADJACENT STATES BY FRANK LEVERETT WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY FREDERICK w. SARDE;30N Investigations made in cooperation with the MINNESOTA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1932 ·For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ________________________________________ _ 1 Wisconsin red drift-Continued. Introduction _____________________________________ _ 1 Weak moraines, etc.-Continued. Scope of field work ____________________________ _ 1 Beroun moraine _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 47 Earlier reports ________________________________ _ .2 Location__________ _ __ ____ _ _ __ ___ ______ 47 Glacial gathering grounds and ice lobes _________ _ 3 Topography___________________________ 47 Outline of the Pleistocene series of glacial deposits_ 3 Constitution of the drift in relation to rock The oldest or Nebraskan drift ______________ _ 5 outcrops____________________________ 48 Aftonian soil and Nebraskan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Striae _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 48 Kansan drift _____________________________ _ 5 Ground moraine inside of Beroun moraine_ 48 Yarmouth beds and Kansan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Mille Lacs morainic system_____________________ 48 Pre-Illinoian loess (Loveland loess) __________ _ 6 Location__________________________________ -

Trip F the PINNACLE HILLS and the MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A

F-1 Trip F THE PINNACLE HILLS AND THE MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A. Sanders Department of Geosciences Monroe Community College INTRODUCTION The Pinnacle Hills, fortunately, were voluminously described with many excellent photographs by Fairchild, (1923). In 1973 the Range still stands as a conspicuous east-west ridge extending from the town of Brighton, at about Hillside Avenue, four miles to the Genesee River at the University of Rochester campus, referred to as Oak Hill. But, for over thirty years the Range was butchered for sand and gravel, which was both a crime and blessing from the geological point of view (plates I-VI). First, it destroyed the original land form shapes which were subsequently covered with man-made structures drawing the shade on its original beauty. Secondly, it allowed study of its structure by a man with a brilliantly analytical mind, Herman L. Fair child. It is an excellent example of morainal deposition at an ice front in a state of dynamic equilibrium, except for minor fluctuations. The Mendon Kame area on the other hand, represents the result of a block of stagnant ice, probably detached and draped over drumlins and drumloidal hills, melting away with tunnels, crevasses, and per foration deposits spilling or squirting their included debris over a more or less square area leaving topographically high kames and esker F-2 segments with many kettles and a large central area of impounded drainage. There appears to be several wave-cut levels at around the + 700 1 Lake Dana level, (Fairchild, 1923). The author in no way pretends to be a Pleistocene expert, but an attempt is made to give a few possible interpretations of the many diverse forms found in the Mendon Kames area. -

Glacial Geomorphology Recording Glacier Recession Since the Little Ice Age.', Journal of Maps., 13 (2)

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 02 May 2017 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Evans, David J. A. and Ewertowski, Marek and Orton, Chris (2017) 'Skaftafellsj¤okull,Iceland : glacial geomorphology recording glacier recession since the Little Ice Age.', Journal of maps., 13 (2). pp. 358-368. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2017.1310676 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor Francis Group on behalf of Journal of Maps This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Journal of Maps ISSN: (Print) 1744-5647 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tjom20 Skaftafellsjökull, Iceland: glacial geomorphology recording glacier recession since the Little Ice Age David J. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

The Urban Geography of Saginaw, Michigan

Wayne State University Wayne State University Theses 1-1-1933 The rbU an Geography of Saginaw, Michigan Dennis Glenn Cooper Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_theses Part of the Geography Commons, History Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Dennis Glenn, "The rU ban Geography of Saginaw, Michigan" (1933). Wayne State University Theses. Paper 465. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE URBAN GEOGRAPHY OF SAGINAW, MICHIGAN A Thesis SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE COLLEGES OF THE CITY OF DETROIT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS. BY Dennis Glen Cooper Detroit, Michigan 1933 t a b l e o f c o n t e n t s I. O u t l i n e ...................... ill II. List of maps, graphs, ana pictures............. vi III. THE URBAN GEOGRAPHY OF SAG INAL, MICHIGAN. 1 IV. Appendix . .......... « . .... 59 V. Bibliography ....................... • 62 f ii THE URBAN GEOGRAPHY OF SAGINAW, MICHIGAN. Outline Page A. Outstanding characteristics of the city............ • 1 1, Unusual landscape pattern with tvvc distinct nuclei 2. Industrial development in transition stage between period of extractive activities and diversified industries B. General situation: the Saginaw Basin • *.*•••* 2 1. Topography 2. Soil 3* Climate 4, Natural resources 5, Drainage C* Site • 4 1* Position of glacial moraine crossing valley 2. Bluff cut in moraine at outer bend and on west side of river 3. -

Crag-And-Tail Features on the Amundsen Sea Continental Shelf, West Antarctica

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on November 30, 2016 Crag-and-tail features on the Amundsen Sea continental shelf, West Antarctica F. O. NITSCHE1*, R. D. LARTER2, K. GOHL3, A. G. C. GRAHAM4 & G. KUHN3 1Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA 2British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 3Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Am Alten Hafen 26, D-27568 Bremerhaven, Germany 4College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Rennes Drive, Exeter EX4 4RJ, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) On parts of glaciated continental margins, especially the inner leads to its characteristic tapering and allows formation of the sec- shelves around Antarctica, grounded ice has removed pre-existing ondary features. Multiple, elongated ridges in the tail could be sedimentary cover, leaving subglacial bedforms on eroded sub- related to the unevenness of the top of the ‘crags’. Secondary, strates (Anderson et al. 2001; Wellner et al. 2001). While the smaller crag-and-tail features might reflect variations in the under- dominant subglacial bedforms often follow a distinct, relatively lying substrate or ice-flow dynamics. uniform pattern that can be related to overall trends in palaeo- While the length-to-width ratio of crag-and-tail features in this ice flow and substrate geology (Wellner et al. 2006), others are case is much lower than for drumlins or elongate lineations, the more randomly distributed and may reflect local substrate varia- boundary between feature classes is indistinct. -

Analysis of Groundwater Flow Beneath Ice Sheets

SE0100146 Technical Report TR-01-06 Analysis of groundwater flow beneath ice sheets Boulton G S, Zatsepin S, Maillot B University of Edinburgh Department of Geology and Geophysics March 2001 Svensk Karnbranslehantering AB Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co Box 5864 SE-102 40 Stockholm Sweden Tel 08-459 84 00 +46 8 459 84 00 Fax 08-661 57 19 +46 8 661 57 19 32/ 23 PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ALL OF THE MISSING PAGES IN THIS DOCUMENT WERE ORIGINALLY BLANK Analysis of groundwater flow beneath ice sheets Boulton G S, Zatsepin S, Maillot B University of Edinburgh Department of Geology and Geophysics March 2001 This report concerns a study which was conducted for SKB. The conclusions and viewpoints presented in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily coincide with those of the client. Summary The large-scale pattern of subglacial groundwater flow beneath European ice sheets was analysed in a previous report /Boulton and others, 1999/. It was based on a two- dimensional flowline model. In this report, the analysis is extended to three dimensions by exploring the interactions between groundwater and tunnel flow. A theory is develop- ed which suggests that the large-scale geometry of the hydraulic system beneath an ice sheet is a coupled, self-organising system. In this system the pressure distribution along tunnels is a function of discharge derived from basal meltwater delivered to tunnels by groundwater flow, and the pressure along tunnels itself sets the base pressure which determines the geometry of catchments and flow towards the tunnel.