Glacial Geology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisconsinan and Sangamonian Type Sections of Central Illinois

557 IL6gu Buidebook 21 COPY no. 21 OFFICE Wisconsinan and Sangamonian type sections of central Illinois E. Donald McKay Ninth Biennial Meeting, American Quaternary Association University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 31 -June 6, 1986 Sponsored by the Illinois State Geological and Water Surveys, the Illinois State Museum, and the University of Illinois Departments of Geology, Geography, and Anthropology Wisconsinan and Sangamonian type sections of central Illinois Leaders E. Donald McKay Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois Alan D. Ham Dickson Mounds Museum, Lewistown, Illinois Contributors Leon R. Follmer Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois Francis F. King James E. King Illinois State Museum, Springfield, Illinois Alan V. Morgan Anne Morgan University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada American Quaternary Association Ninth Biennial Meeting, May 31 -June 6, 1986 Urbana-Champaign, Illinois ISGS Guidebook 21 Reprinted 1990 ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Morris W Leighton, Chief 615 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/wisconsinansanga21mcka Contents Introduction 1 Stopl The Farm Creek Section: A Notable Pleistocene Section 7 E. Donald McKay and Leon R. Follmer Stop 2 The Dickson Mounds Museum 25 Alan D. Ham Stop 3 Athens Quarry Sections: Type Locality of the Sangamon Soil 27 Leon R. Follmer, E. Donald McKay, James E. King and Francis B. King References 41 Appendix 1. Comparison of the Complete Soil Profile and a Weathering Profile 45 in a Rock (from Follmer, 1984) Appendix 2. A Preliminary Note on Fossil Insect Faunas from Central Illinois 46 Alan V. -

Disappearing Kettle Ponds Reveal a Drying Kenai Peninsula by Ed Berg

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 3, No. 38 • October 12, 2001 Disappearing kettle ponds reveal a drying Kenai Peninsula by Ed Berg A typical transect starts at the forest edge, passes through a grass (Calamagrostis) zone, into Sphagnum peat moss, and then into wet sedges, sometimes with pools of standing water, and then back through these same zones on the other side of the kettle. Three of the four kettles we surveyed this summer were quite wet in the middle (especially after the July rains), and we had to wear hip boots. These plots can be resurveyed in future decades and, if I am correct, they will show a succession of drier and drier plants as the water table drops lower and lower, due to warmer summers and increased evap- Photo of a kettle pond by the National Park Service. otranspiration. If I am wrong, and the climate trend turns around toward cooler and wetter, these plots will When the glaciers left the Soldotna-Sterling area be under water again, as they were on the old aerial some 14,000 years ago, the glacier fronts didn’t re- photos. cede smoothly like their modern descendants, such as By far the most striking feature that we have Portage or Skilak glaciers. observed in the kettles is a band of young spruce Rather, the flat-lying ice sheets broke up into nu- seedlings popping up in the grass zones. These merous blocks, which became partially buried in hilly seedlings can form a halo around the perimeter of a moraines and flat outwash plains. In time these gi- kettle. -

Vegetation and Fire at the Last Glacial Maximum in Tropical South America

Past Climate Variability in South America and Surrounding Regions Developments in Paleoenvironmental Research VOLUME 14 Aims and Scope: Paleoenvironmental research continues to enjoy tremendous interest and progress in the scientific community. The overall aims and scope of the Developments in Paleoenvironmental Research book series is to capture this excitement and doc- ument these developments. Volumes related to any aspect of paleoenvironmental research, encompassing any time period, are within the scope of the series. For example, relevant topics include studies focused on terrestrial, peatland, lacustrine, riverine, estuarine, and marine systems, ice cores, cave deposits, palynology, iso- topes, geochemistry, sedimentology, paleontology, etc. Methodological and taxo- nomic volumes relevant to paleoenvironmental research are also encouraged. The series will include edited volumes on a particular subject, geographic region, or time period, conference and workshop proceedings, as well as monographs. Prospective authors and/or editors should consult the series editor for more details. The series editor also welcomes any comments or suggestions for future volumes. EDITOR AND BOARD OF ADVISORS Series Editor: John P. Smol, Queen’s University, Canada Advisory Board: Keith Alverson, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC), UNESCO, France H. John B. Birks, University of Bergen and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Norway Raymond S. Bradley, University of Massachusetts, USA Glen M. MacDonald, University of California, USA For futher -

WELLESLEY TRAILS Self-Guided Walk

WELLESLEY TRAILS Self-Guided Walk The Wellesley Trails Committee’s guided walks scheduled for spring 2021 are canceled due to Covid-19 restrictions. But… we encourage you to take a self-guided walk in the woods without us! (Masked and socially distanced from others outside your group, of course) Geologic Features Look for geological features noted in many of our Self-Guided Trail Walks. Featured here is a large rock polished by the glacier at Devil’s Slide, an esker in the Town Forest (pictured), and a kettle hole and glacial erratic at Kelly Memorial Park. Devil’s Slide 0.15 miles, 15 minutes Location and Parking Park along the road at the Devil’s Slide trailhead across the road from 9 Greenwood Road. Directions From the Hills Post Office on Washington Street, turn onto Cliff Road and follow for 0.4 mile. Turn left onto Cushing Road and follow as it winds around for 0.15 mile. Turn left onto Greenwood Road, and immediately on your left is the trailhead in patch of woods. Walk Description Follow the path for about 100 yards to a large rock called the Devil’s Slide. Take the path to the left and climb around the back of the rock to get to the top of the slide. Children like to try out the slide, which is well worn with use, but only if it is dry and not wet or icy! Devil’s Slide is one of the oldest rocks in Wellesley, more than 600,000,000 years old and is a diorite intrusion into granite rock. -

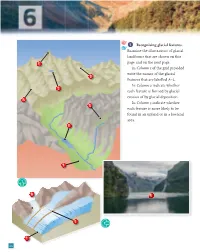

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Living on the Edge

Living on the Ledge Life in Eastern Wisconsin Outline • Location of Niagara Escarpment Eastern U.S. • General geology • Locations of the escarpment in Wisconsin • Neda Iron mine and early geologists • Silurian Dolostone of Waukesha Co.- Lannon Stone , past and present quarries • The Great Lakes Watershed Niagara Falls NY – Rock falls caused by undercutting: notice the pile of broken rock at base of American falls. Top Layer is equivalent to Waukesha/ Lannon Stone You may have see Niagara Falls locally if you visited the Hudson River painters exhibit at MAM. Fredrick Church 1867 Fredrick Church 1857 Or you can see a bit of the Ledge as a table top while meditating with a bottle of Silurian Stout in my yard Fr. Louis Hennepin sketch of Niagara Falls 1698 Niagara Falls - the equivalent stratigraphic section in N.Y. from which the correlation of the Neda to the Clinton Iron was incorrectly made Waterfalls associated with the Niagara Escarpment all follow this pattern- resistant cap rock and soft shale underneath The “Ledge” of Western NY The Niagara Escarpment Erie Canal locks at Lockport NY The Erie Canal that followed the lowland until it reached the Niagara Escarpment The names of Silurian rocks in the Midwestern states change with location and sometimes with authors! 417mya Stratigraphic column for rocks of Eastern Wisconsin. 443mya Note the Niagara Escarpment rocks at the top. The Escarpment is the result of resistant dolostone 495mya cap rock and soft shale rock below The Michigan Basin- Showing outcrops of Silurian rocks Location of major Silurian Outcrops in Eastern Wisconsin Peninsula Park from both top and bottom Ephraim Sven’s Overlook Door County – Fish Creek Niagara Escarpment in the background Door Co Shoreline Cave Point near Jacksonport - Door Co Cave Point - 2013 Cave Point - Door Co - 2013 during low lake levels Jean Nicolet 1634 overlooking Green Bay WI while standing on the Ledge Wequiock Falls near Green Bay WI. -

Ground-Water Conditions in the Milwaukee-Waukesha Area, Wisconsin

Ground-Water Conditions in the Milwaukee-Waukesha Area, Wisconsin GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1229 Ground-Water Conditions in the Milwaukee -Waukesha Area, Wisconsin By F. C. FOLEY, W. C. WALTON, and W. J. DRESCHER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1229 A progress report, with emphasis on the artesian sandstone aquifer. Prepared in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1953 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director f For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 70 cents CONTENTS Page Abstract.............................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................ 3 Purpose and scope of report.................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments...................................................................................................... 5 Description of the area............................................................................................ 6 Previous reports........................................................................................................ 6 Well-numbering system.............................................................................................. 7 Stratigraphy....................................................................................................................... -

Exploring Wisconsin Geology

UW Green Bay Lifelong Learning Institute January 7, 2020 Exploring Wisconsin Geology With GIS Mapping Instructor: Jeff DuMez Introduction This course will teach you how to access and interact with a new online GIS map revealing Wisconsin’s fascinating past and present geology. This online map shows off the state’s famous glacial landforms in amazing detail using new datasets derived from LiDAR technology. The map breathes new life into hundreds of older geology maps that have been scanned and georeferenced as map layers in the GIS app. The GIS map also lets you Exploring Wisconsin Geology with GIS mapping find and interact with thousands of bedrock outcrop locations, many of which have attached descriptions, sketches, or photos. Tap the GIS map to view a summary of the surface and bedrock geology of the area chosen. The map integrates data from the Wisconsin Geological & Natural History Survey, the United States Geological Survey, and other sources. How to access the online map on your computer, tablet, or smart phone The Wisconsin Geology GIS map can be used with any internet web browser. It also works on tablets and on smartphones which makes it useful for field trips. You do not have to install any special software or download an app; The map functions as a web site within your existing web browser simply by going to this URL (click here) or if you need a website address to type in enter: https://tinyurl.com/WiscoGeology If you lose this web site address, go to Google or any search engine and enter a search for “Wisconsin Geology GIS Map” to find it. -

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage Into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water Reinhard Hesse*, Ingo Klaucke, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2A7, Canada William B. F. Ryan, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964-8000 Margo B. Edwards, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822 David J. W. Piper, Geological Survey of Canada—Atlantic, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4A2, Canada NAMOC Study Group† ABSTRACT the western Atlantic, some 5000 to 6000 State-of-the-art sidescan-sonar imagery provides a bird’s-eye view of the giant km from their source. submarine drainage system of the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel Drainage of the ice sheet involved (NAMOC) in the Labrador Sea and reveals the far-reaching effects of drainage of the repeated collapse of the ice dome over Pleistocene Laurentide Ice Sheet into the deep sea. Two large-scale depositional Hudson Bay, releasing vast numbers of ice- systems resulting from this drainage, one mud dominated and the other sand bergs from the Hudson Strait ice stream in dominated, are juxtaposed. The mud-dominated system is associated with the short time spans. The repeat interval was meandering NAMOC, whereas the sand-dominated one forms a giant submarine on the order of 104 yr. These dramatic ice- braid plain, which onlaps the eastern NAMOC levee. This dichotomy is the result of rafting events, named Heinrich events grain-size separation on an enormous scale, induced by ice-margin sifting off the (Broecker et al., 1992), occurred through- Hudson Strait outlet. -

2. Blue Hills 2001

Figure 1. Major landscape regions and extent of glaciation in Wisconsin. The most recent ice sheet, the Laurentide, was centered in northern Canada and stretched eastward to the Atlantic Ocean, north to the Arctic Ocean, west to Montana, and southward into the upper Midwest. Six lobes of the Laurentide Ice Sheet entered Wisconsin. Scale 1:500,000 10 0 10 20 30 PERHAPS IT TAKES A PRACTICED EYE to appreciate the landscapes of Wisconsin. To some, MILES Wisconsin landscapes lack drama—there are no skyscraping mountains, no monu- 10 0 10 20 30 40 50 mental canyons. But to others, drama lies in the more subtle beauty of prairie and KILOMETERS savanna, of rocky hillsides and rolling agricultural fi elds, of hillocks and hollows. Wisconsin Transverse Mercator Projection The origin of these contrasting landscapes can be traced back to their geologic heritage. North American Datum 1983, 1991 adjustment Wisconsin can be divided into three major regions on the basis of this heritage (fi g. 1). The fi rst region, the Driftless Area, appears never to have been overrun by glaciers and 2001 represents one of the most rugged landscapes in the state. This region, in southwestern Wisconsin, contains a well developed drainage network of stream valleys and ridges that form branching, tree-like patterns on the map. A second region— the northern and eastern parts of the state—was most recently glaciated by lobes of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which reached its maximum extent about 20,000 years ago. Myriad hills, ridges, plains, and lakes characterize this region. A third region includes the central to western and south-central parts of the state that were glaciated during advances of earlier ice sheets. -

An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250

The Ohio Naturalist, PUBLISHED BY The Biological Club of the Ohio State University. Volume VIII. JANUARY. 1908. No. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS. SCHEPFEL—An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250 AN ESKER GROUP SOUTH OF DAYTON, OHIO.1 EARL R. SCHEFFEL Contents. Introduction. General Discussion of Eskers. Preliminary Description of Region. Bearing on Archaeology. Topographic Relations. Theories of Origin. Detailed Description of Eskers. Kame Area to the West of Eskers. Studies. Proximity of Eskers. Altitude of These Deposits. Height of Eskers. Composition of Eskers. Reticulation. Rock Weathering. Knolls. Crest-Lines. Economic Importance. Area to the East. Conclusion and Summary. Introduction. This paper has for its object the discussion of an esker group2 south of Dayton, Ohio;3 which group constitutes a part of the first or outer moraine of the Miami Lobe of the Late Wisconsin ice where it forms the east bluff of the Great Miami River south of Dayton.4 1. Given before the Ohio Academy of Science, Nov. 30, 1907, at Oxford, O., repre- senting work performed under the direction of Professor Frank Carney as partial requirement for the Master's Degree. 2. F: G. Clapp, Jour, of Geol., Vol. XII, (1904), pp. 203-210. 3. The writer's attention was first called to the group the past year under the name "Morainic Ridges," by Professor W. B. Werthner, of Steele High School, located in the city mentioned. Professor Werthner stated that Professor August P. Foerste of the same school and himself had spent some time together in the study of this region, but that the field was still clear for inves- tigation and publication. -

Quarrernary GEOLOGY of MINNESOTA and PARTS of ADJACENT STATES

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Ray Lyman ,Wilbur, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director P~ofessional Paper 161 . QUArrERNARY GEOLOGY OF MINNESOTA AND PARTS OF ADJACENT STATES BY FRANK LEVERETT WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY FREDERICK w. SARDE;30N Investigations made in cooperation with the MINNESOTA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1932 ·For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ________________________________________ _ 1 Wisconsin red drift-Continued. Introduction _____________________________________ _ 1 Weak moraines, etc.-Continued. Scope of field work ____________________________ _ 1 Beroun moraine _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 47 Earlier reports ________________________________ _ .2 Location__________ _ __ ____ _ _ __ ___ ______ 47 Glacial gathering grounds and ice lobes _________ _ 3 Topography___________________________ 47 Outline of the Pleistocene series of glacial deposits_ 3 Constitution of the drift in relation to rock The oldest or Nebraskan drift ______________ _ 5 outcrops____________________________ 48 Aftonian soil and Nebraskan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Striae _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 48 Kansan drift _____________________________ _ 5 Ground moraine inside of Beroun moraine_ 48 Yarmouth beds and Kansan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Mille Lacs morainic system_____________________ 48 Pre-Illinoian loess (Loveland loess) __________ _ 6 Location__________________________________