Complete Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grusswort Der Beauftragten Der Bundesregierung Für Kultur Und Medien

GRUSSWORT DER BEAUFTRAGTEN DER BUNDESREGIERUNG FÜR KULTUR UND MEDIEN »Denn ichs mit den bilderstürmen nicht halte«, sagte Martin Luther und trat damit Anfang der zwanziger Jahre des 16. Jahrhunderts entschieden denen entgegen, die den Kirchenraum von bildlichen Darstellungen säubern wollten. Zu Recht! Er hatte Freude an der Kunst und wusste um den Wert von Bildern, die seine reformatorische Bot- schaft transportierten. Seine Freundschaft mit der ihm eng verbundenen Malerfamilie Cranach hielt ein Leben lang. Mit dem Projekt »Cranachs Kirche« wäre er daher sicherlich sehr einverstanden ge- wesen, denn durch die Verbindung von Architektur und Ausstellung öffnet sich in der Wittenberger Stadtkirche St. Marien den Besucherinnen und Besuchern ein neuer Blick auf die Reformatoren und ihre Zeit. St. Marien gilt als »Mutterkirche der Reformation«. Martin Luther selbst, Philipp Melanchthon und Johannes Bugenhagen haben hier ge- predigt. Als authentische Reformationsstätte gehört sie zum UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe und ist allein deshalb von höchstem kunsthistorischem Wert. Ein besonderer Focus aber richtet sich an diesem Ort mit »Cranachs Kirche« auf den Maler Lucas Cranach d. J., dessen 500. Geburtstag wir im aktuellen Themenjahr der Lutherdekade »Reforma- tion – Bild und Bibel« begehen. Für ihn war diese Kirche von besonderer Bedeutung: Hier wurde er wahrscheinlich getauft, hier hörte er die Predigten der Reformatoren, hier befinden sich Grab und Epitaph. Und hier steht der wunderbare Reformationsaltar, der bisher als eines der Hauptwerke seines Vaters, Lucas Cranachs d. Ä., weltweit bekannt war. Doch wäre der Altar ohne den Beitrag seines Sohnes nicht der, den wir nach seiner Restaurierung in seiner ganzen Ausdruckskraft erleben dürfen. Der Altar, aber auch an- dere Tafelbilder wie das ebenfalls berühmte Weinbergbild und die Epitaphe, vermitteln den Besucherinnen und Besuchern jeweils eigene Aspekte der Reformationsgeschichte. -

Lutherrejse 2018 - Tilmelding Senest 1.11 2017

LUTHERREJSE 2018 - TILMELDING SENEST 1.11 2017 Depositum betales senest 15.11: 500,- kr. på kontonr. i Danske Bank: 4424 0009824235. Husk tydelig afsender i kontomeddelelse. Restbeløbet fremsendes til deltager pr. mail eller post inden 31.12, betales senest 1.2.2018. Navn; Adresse: Tlf.: Mobil: Email: Kontaktperson i Danmark, navn, relation, email og tlf: Dobbeltværelse, sæt kryds: Enkeltværelse (+ 750 kr.), sæt kryds: Årsafbestillingsforsikring, sæt kryds + fødselsdato: Årsrejseforsikring, sæt kryds + fødselsdato: Pris 4.898- pr. person i dobbeltværelse ved 20 – 30 deltagere 4.198,- pr. person i dobbeltværelser ved 31 – 40 deltagere. *4.098,- pr person i dobbeltværelse ved 41-50 deltagere. Tillæg for eneværelse: 750,- Tillæg årsrejseforsikring (under 69 år): 249,- Tillæg årsrejseforsikring (70-79 år): 374,- Tillæg årsrejseforsikring (80+): 498,- Tillæg årsafbestillingsforsikring: 269,- * Tillæg for entre og udflugt: 450, -, dvs, i alt. 5348 kr. ved 20-30 deltagere. En evt. reduktion vil fremgå af endelige indbetalingsbeløb. Prisen inkluderer Bus + Færgeoverfart Rødby – Puttgarden t/r, 4 overnatninger, 4 x morgenmad, 4 x aftensmad, samt rejseleder Kristian Massey Møller Prisen inkluderer ikke Øvrige måltider og drikkevarer Udflugter, 450 kr. (incl. mulig kanalfart i Berlin) som tillægges prisen. Afbestillingsforsikring Rejseforsikring Dato og underskrift LUTHERREJSE 16.4-20.4.2018 – MED HANSTHOLM REJSER Nøgleord: Tid, hygge, spise og ånd – Langsomhed og tålmodighed. FØRSTE DAG - AFGANG: Mandag morgen Odden til Rødby. 200 km. 2½ time. Rødby – Puttgarden. Sejltid 45 minutter. Puttgarden-Erfurt. 500 km. Køretid med pauser 6 timer. Kl. 18. Aftensmad på hotel. MERCURE HOTEL ERFURT ALSTADT. 2 overnatninger. Erfurt har 200.000 indbyggere. Hovedstad i Thüringen. 600 meter til Domkirkepladsen med Mariedom og Severikirche. -

Alles Luther Oder Was?

Alles Luther oder was? Sein(e) dein(e) Zeit Angst Entdeckung Mut + Begleitmaterial: bestellen oder downloaden unter Projekt ? www.gotteswort.schule Luthers MUT ... iNHALT ... begann mit einer Erfahrung, die Luthers ZEIT ... sein Leben total veränderte und ... ist einzigartig. Einzigartig ist die du auch machen kannst. auch die Zeit, die Gott dir zum Seite 16-19 Leben schenkt. Seite 4-7 Luthers PROJEKT ... ... „Bibelübersetzung“ Luthers ANGST ... (siehe Angebot auf der Rückseite) ... ließ ihn fast verzweifeln – bis Gott eingriff! Seite 8-11 Seite 20-23 Die Barmherzigkeit Gottes ist wie der Himmel, der Luthers ENTDECKUNG ... stets über uns fest bleibt. Unter ... kann deine werden! diesem Dach sind wir sicher, wo auch immer wir sind. Seite 12-15 – Martin Luther – Bildnachweise (sofern nicht am Bild angegeben): Seite 11: G. Werner / Seite 7, 13, 15, 19, 20: fotolia.de / Seite 1, 8, 9, 13, 20, 21: panthermedia.de Seite 16: WikipediaCommons / Luther-Porträt Umschlag und Innenteil: E.-C. Zawinell; Aquarell-Motive: J. Wald / alle anderen Fotos: Pixabay.com Die Bibel ist nicht Luthers ZEIT antik, auch nicht modern, sie ist ewig. – Martin Luther – Luthers Eltern Hans und Margarethe Lutherhaus Eisleben Wo lebte Luther? Was war damals los? Luthers Kindheit Dort leben Verwandte seiner Mutter. Martin Luther kommt am 10. Novem- Die Zeit Luthers ist heftig turbulent. Als Kolumbus mit der Santa Maria ins Mit 17 hat er die Schule geschafft und ber 1483 in Eisleben 1 zur Welt. Die Türken sind unter ihrem Sultan Unbekannte segelt und 1492 Amerika kann fließend Latein lesen, schreiben Eisleben, das liegt in Sachsen-Anhalt Mehmet II. im Jahr 1480 bis Südita- entdeckt, drückt der 9-jährige Luther und sprechen. -

Gäste Journal Guest Magazine

Gäste Journal Guest Magazine September-Oktober 2012 Eröffnung Einkaufscenter ARSENAL WITTENBERG Veranstaltungen Gastronomie Ausfl ugstipps Neueröffnung Arsenal & vieles mehr! kostenlose Urlaubshotline: 0800 2020 114 [email protected] international: +49 3491 4986 - 10 www.lutherstadt-wittenberg.de 2 SEPT.-OKTOBER Inhalt · Service 3 INHALT Mit freundlicher Unterstützung von: ® Die Tourist-Information Inhalt und Service 3 .................................................... Lutherstadt Wittenberg Veranstaltungs-Tipps 4 – 5 .................................................... Unsere Services für Sie: Stadt- und Eventführungen 6 Kostenlose Beratung zu Aufenthalten, .................................................... Aktivitäten und Angeboten in der Lutherstadt Urlaubs-Angebote 7 .................................................... Wittenberg und in der umliegenden Region Zusendung von Informationsmaterial Veranstaltungen/Austellungen 8 – 12 .................................................... kostenloser Online-Newsletter Kultur-Tipp 13 Vermittlung von Hotels, Pensionen, .................................................... Ferienhäusern und Ferienwohnungen Stadtplan / City Map 14 – 15 Gruppenangebote/-reservierungen .................................................... Pauschalangebote/Last-Minute-Börse/ Sehenswürdigkeiten 16 – 17 .................................................... Online-Buchung und -Anfrage Begrüßungsfi lm-Vorführung für Gäste Regelmäßige Veranstaltungen 18 Am Hauptbahnhof 3 · 06886 Lutherstadt Wittenberg -

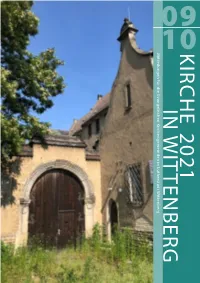

Kirche 2021 in Wit Tenberg

KIRCHE 2021 09 10 IN WITTENBERG Mitteilungen für die Evangelischen Kirchengemeinden in Lutherstadt Wittenberg !” “Ich bin hindurch!” Martin Luther atmete vor 500 Jahren auf. Er hatte die Vorladung vor den Reichstag in Worms im Jahr 1521 überstanden. Besorgt war der Reformator über die Schwelle zur Reichstagsversammlung getreten und erleichtert ging er durch das Portal hinaus: „Ich bin hindurch!“ – Immer wieder treten Menschen über Schwellen und gehen durch HINDURCH Türen hindurch: mit Sorgen und Ängsten, mit Erleichterung und Befreiung. 500 Jahre nach dem Reichstag in Worms stellen die Titelbilder des Mitteilungsblattes 2021 Wittenberger Portale und Türen vor, durch die Menschen mit unterschiedlichen Gefühlen und Erwartungen gehen. BIN Eine Tür in den Knast Die Tür führte in das Wittenberger Gefängnis. Und sie führte heraus aus demselben in ICH die Freiheit. Die Richtung, mit der man durch diese Tür ging, war also von größter Wichtigkeit. Hinein bedeutete, dass man für einige Zeit in großer Unfreiheit bei „ schlechtem Essen, monotoner Arbeit, Langeweile und Einsamkeit sein Leben fristen musste als Strafe für kleine und große Verbrechen, die man begangen hatte oder die einen zumindest nachgewiesen werden konnten. Gefängnisse gehören mit Kasernen zu den trostlosesten Bauten. Das 1909 erbaute Wittenberger Gefängnis, damals das modernste in Deutschland, war nicht ganz so trostlos. Es besaß sogar eine Turnhalle – eine humanistische Errungenschaft des Pfarrers und Gefängnisreformers Johann Hinrich Wichern. Wegen der mangelnden Größe (nur ca. 55 Zellen) wurde der Witten- berger Gefängnisbau bald zu ineffektiv und zu teuer. Und so schloss man 1965 den Knast. Größere Gefängnisse übernahmen fortan die „Beherbergung“ der Straftäter. In dem Bau aus wilhelminischer Ära waren dann zeitweilig der Katastrophenschutz und das Grundbuchamt untergebracht. -

Die Neue Imagebroschüre Der Stadt Als

Wussten Sie’s schon? Die Lutherstadt Wittenberg Luthereiche 1610 Stiefeltrinken steht nicht nur für Luthers Die Luthereiche steht am südlichen Ende der Michael Stifel, ein Pfarrer und Freund Luthers, verkündete den Collegienstraße, dort, wo Martin Luther 1520 Medizinische Weltuntergang für den 19. Oktober 1533. Der hat bekanntlich Thesenanschlag von 1517, die Bannbulle des Papstes verbrannte. seitdem ein wenig Verspätung. Ein Spottlied entstand: „Stifel Großtat muss sterben, ist noch so jung“ – zur feuchtfröhlichen Begleitung sondern auch für einige entwickelte sich die Sitte des Stiefeltrinkens. Am 21. April 1610 führt der Bader erstaunliche und manche Jeremias Trautmann hier den ersten kuriose Begebenheiten. dokumentierten Kaiserschnitt der 973 Geschichte durch. wurde das Territorium der heu Vier auf Urgroßvater tigen Lutherstadt Wittenberg Die Hand der erstmals erwähnt. des Giftmischerin einen Berlin oder Leipzig? Dank Die Giftmischerin Susanne Zimmermann beförderte zwei Streich der ICE-Verbindung kann Ehemänner und drei Kinder ins Jenseits, dazu die Schwägerin Handys und ein Kindermädchen. Ihre mumifizierte Hand sorgt in man entspannt in der den Städtischen Sammlungen der Stadt noch heute für ent 1833 konstruiert Wilhelm Weber sprechenden Grusel bei Groß und Klein. Viermal UNESCO- zusammen mit Carl Friedrich Hauptstadt frühstücken, Gauß den ersten elektromagne in Lutherstadt Wittenberg Weltkulturerbestätten tischen Telegrafen. Das Geburts 30 haus des berühmten Stadtsohnes, mittagessen und abends in das WeberHaus, steht in der -

Übersetzung Sehenswürdigkeiten Und Geschichte Der Lutherstadt Wittenberg

Übersetzung Sehenswürdigkeiten und Geschichte der Lutherstadt Wittenberg Stand 17.01.2018 Deutsch Englisch 95 Thesen 95 Theses Ablass indulgence Abzug der sowjetischen Truppen withdrawal of Soviet troops Alaris Schmetterlingspark Alaris Butterfly Park Altes Collegium Old College Altes Jungfernröhrwasser Old Virgin Piped Water Altes Rathaus Old Town Hall Altstadt old town Amselgrund Amselgrund Andreasbreite Andreasbreite Apotheke pharmacy Arche (Gewässer wurden mit Hilfe sogenannter ‘ark’ (wooden trough used to Archen, Holzkonstruktionen, in die Stadt geleitet) transport river water into the town) Panorama LUTHER 1517 von Yadegar Asisi Panorama LUTHER 1517 by Yadegar Asisi Askanier House of Ascania Auflösung der Klöster dissolution of monasteries, suppression of monasteries Augsburgische Konfession Augsburg Confession Augusteum Augusteum autofreie Siedlung car-free housing estate barrierefrei accessible Bastion Cavalier Cavalier Bastion Bastion Tauentzien Tauentzien Bastion Batteriestein Battery Stone Begräbnisstätte der Professoren [Schlosskirche] last resting place for prominent scholars Bronzetür [Schlosskirche] bronze door Bugenhagenhaus Bugenhagen House Bunkerberg Bunker Hill Campingplatz Marina-Camp Elbe Marina Campsite Casinogarten officers’ mess garden Christine-Bourbeck-Haus Christine Bourbeck House Clack Theater Clack Theatre Colleg Wittenberg Colleg Wittenberg Cranachhaus Cranach House Cranach-Hof, Markt 4 Cranach Courtyard, Markt 4 Cranach-Hof, Schlossstraße 1 Cranach Courtyard, Schlossstrasse 1 Cranach-Höfe Cranach Courtyards -

Gästejournal Mai | Juni | Juli | August 2017

GÄSTEJOURNAL MAI | JUNI | JULI | AUGUST 2017 +49 3491 4986 - 10 Kostenlose Urlaubshotline: 0800 2020 114 [email protected] www.lutherstadt-wittenberg.de 90 SHOPS, MO. BIS SA. 9.30– 20 UHR, 850 PARKPLÄTZE 17.12.15 11:55 Finde uns auf Facebook RCD265 AZ Gästejournal 2016 210x148.indd 1 MAI 3 AUGUST INHALT | ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN | SERVICE INHALT HIER ERHALTEN SIE AUCH Inhalt | Öffnungszeiten | Service 3 AKTUELLE VERANSTALTUNGSTIPPS . UND TICKETS! Sehenswürdigkeiten 4 – 7 . Schlossplatz 2 Aus dem Ausland +49 3491 - 49 86 10 Stadtplan 8 – 9 . 06886 Lutherstadt Wittenberg Fax +49 3491 - 49 86 11 Stadt- und Eventführungen 10 – 11 Kostenlose Urlaubshotline [email protected] . Altstadtbahn und Elbeschifffahrt 12 0800 20 20 114 www.lutherstadt-wittenberg.de . Luthers Hochzeit 13 . ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN UNSER SERVICE FÜR SIE: Veranstaltungstipps 14 – 17 Kostenlose Beratung zu Aufenthalten, . TOURIST-INFORMATIONEN Aktivitäten und Angeboten in der Lutherstadt Veranstaltungen Clack-Theater 18 – 21 . Wittenberg und in der umliegenden Region • am Schlossplatz Zusendung von Informationsmaterial Veranstaltungstermine 22 – 31 April – Oktober . kostenloser Online-Newsletter täglich 9.00 – 18.00 Uhr Vermittlung von Hotels, Pensionen, Regelmäßige Veranstaltungen 32 . November – März Ferienhäusern und Ferienwohnungen Mo – Fr 10.00 – 16.00 Uhr Gruppenangebote/-reservierungen Reformationsjubiläum 2017 33 . Sa/So/FT: 10.00 – 14.00 Uhr Pauschalangebote/Online-Buchung und -Anfrage Ausstellungen | Highlights 2017 /18 34 – 35 Außerhalb der Öffnungszeiten stehen wir Ihnen . von Mo – Fr von 8.00 bis 20.00 Uhr unter der Ausflugstipps für Lutherstadt Wittenberg Kulturtipp 36 kostenlosen Urlaubshotline 0800 20 20 114 und die umliegende Region . zur Verfügung. Stadt- und Eventführungen Shoppingerlebnis | Souvenirtipp 38 – 39 Verleih von Audio-Guides . -

Von Forschungsdaten Zu Projekten; Aline Deicke

13. Juni 2018 | Aktionstag Forschungsdaten, JGU Mainz VON FORSCHUNGSDATEN ZU -PROJEKTEN NETZWERKE INNERPROTESTANTISCHER STREITKULTUR DES SPÄTEN 16. JH Aline Deicke Digitale Akademie Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur | Mainz GLIEDERUNG 1. Das Projekt „Controversia et Confessio“ 2. Netzwerke innerprotestantischer Streitkultur 01 Das Projekt „Controversia et Confessio“ „Das Projekt dokumentiert die Grundsatzdiskussionen um die authentische Bewahrung von Luthers Erbe, die in der zweiten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts aufbrachen und wesentlich zur Identitätsbildung des Protestantismus Wittenberger Prägung beitrugen.“ (http://www.controversia-et- „Weinberg des Herrn“ – Epitaph für Paul Eber in der confessio.de/) Stadtkirche Wittenberg (1569); https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Weinberg-WB- 1569.jpg PRIMÄRDATEN: PUBLIKATIONSREIHE http://diglib.hab.de/edoc/ed000211/start.htm PRIMÄRDATEN: ONLINEPORTAL • Seit 2014 • Zugriff auf 2063 Quellen, 840 Personen • Übergreifende Recherchemöglichkeit und Registerzugänge (Personen, Quellen, Orte) • Lizensiert unter CC BY 4.0 Lizenz à Open Access www.controversia-et-confessio.de PRIMÄR-/METADATEN: TITELBLATTKATALOG METADATEN: PERSONENREGISTER DATENAUFBEREITUNG: NORMALISIERUNG ... Melanchthon | ... Philippus | Brettanus, Philippus | Didymus (Faventinus) | Didymus Faventinus | Didymus | Faventinus, Didymus | Filipp Melankhton | Filippo Melantone | Germanus, Otho | M., Philippus | Malanth., Philippus | Malanthon, Philipp | Mel., Philippus | Mela., Philippus | Melan., Philippus | Melanc., Philippus -

PDF, in German

INHALT Grußwort 1 Einladung zur Mitgliedervers. 4 Was bedeutet Luther für mich 6 Katharin v. Bora in Hirschfeld 10 Luthers Sohn Johannes 12 Maria - Das Magnificat 14 Förderverein der Bibliothek 18 Familiennachrichten 20 Kinderseite 23 HEFT 64 92. JAHRGANG Heft 217 seit 1926 Juni 2017 Erscheint in zwangloser Folge Der Marktplatz zu Wittenberg - Zum Jubiläumsjahr erstrahlt das Zentrum der Lutherstadt in festlichem Gewand für die Besucher aus aller Welt. Auch die Lutheriden werden zu ihrem Familientag vom 15. - 17. September die Stadt ihres Urahnen besuchen und besichtigen. Foto: Martin Eichler Liebe Lutherverwandte, dazu gehören, so dass man auch kaum noch hinter- herkommt alles zu lesen. vor kurzem las ich in der Presse: „Katholiken und Lutheraner zum Jahr des 500. Reformationsjubilä- An einigen Stellen wird bereits über eine regelrech- ums auf Kuschelkurs.“ te „Luthermanie“ gespottet und mancher beklagt sich auch schon einmal und sagt, dass es nun aber Leider kann ich heute nicht mehr so genau sagen wo langsam reichen würde. Aber neben den Zeitungsar- ich es gelesen habe, denn in diesem Jahr überschla- tikeln, Interviews und Reportagen, scheint es auch, gen sich Presse und Medien mit allerlei Berichten dass Spielfilm und Theater genauso ihren Anteil an über Martin Luther, die Reformation und Dingen die Luther und Co. haben wollen. So hat das Fernsehen 1 in diesem Jahr einen Spielfilm über unsere „Frau Dieses Stück brachte für mich auch eine neue Er- Käthe“ auf den Bildschirm gezaubert, der das Leben fahrung, da ich mit Herrn Zawilla im Vorfeld an von Katharina von Bora beleuchtet. Es ist nicht das dem Stück arbeiten durfte und somit die Möglichkeit einzige Werk, das sich mit Luthers Frau beschäftigt. -

Hinführung Zum Thema

„...quia non habeo aptiora exempla.“ Eine Analyse von Martin Luthers Auseinandersetzung mit dem Mönchtum in seinen Predigten des ersten Jahres nach seiner Rückkehr von der Wartburg 1522/1523 Dissertation Zur Erlangung des Grades der Doktorin Der Theologie Dem Fachbereich Evangelische Theologie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Vera Christina Pabst aus Ulm / Donau Loccum, den 29. März 2005 1. Gutachter: Frau Professor Dr. Inge Mager 2. Gutachter: Herr Professor Dr. Johann Anselm Steiger Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 6. Juli 2005 Inhaltsverzeichnis INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Inhaltsverzeichnis ...................................................................................................... 1 Abkürzungsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 8 Einleitung.................................................................................................................. 10 Kapitel I. Aspekte der Forschung .......................................................................... 16 I. 1 Luther als Mönch und seine sich verändernde Auffassung der Gelübde .... 16 I. 1. 1 Die konfessionell polemisch geprägte Auseinandersetzung um Luther als Mönch und seine Haltung zum Monasmus ...................................................... 16 I. I. 2 Die weitere ökumenische Diskussion über Luthers Verständnis der Gelübde 18 I. 1. 3 Lohses Untersuchung von Luthers Auseinandersetzung mit dem Mönchsideal .................................................................................................... -

Gästejournal September | Oktober | November | Dezember 2017

GÄSTEJOURNAL SEPTEMBER | OKTOBER | NOVEMBER | DEZEMBER 2017 +49 3491 4986 - 10 Kostenlose Urlaubshotline: 0800 2020 114 [email protected] www.lutherstadt-wittenberg.de 90 SHOPS, MO. BIS SA. 9.30– 20 UHR, 850 PARKPLÄTZE 17.12.15 11:55 Finde uns auf Facebook RCD265 AZ Gästejournal 2016 210x148.indd 1 SEPTEMBER 3 DEZEMBER INHALT | ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN | SERVICE INHALT HIER ERHALTEN SIE AUCH Inhalt | Öffnungszeiten | Service 3 AKTUELLE VERANSTALTUNGSTIPPS . UND TICKETS! Sehenswürdigkeiten 4 – 7 . Stadtplan 8 – 9 Schlossplatz 2 Aus dem Ausland +49 3491 - 49 86 10 . 06886 Lutherstadt Wittenberg Fax +49 3491 - 49 86 11 Stadt- und Eventführungen 10 Kostenlose Urlaubshotline [email protected] . Führungen | Regelmäßige Veranstaltungen 11 . 0800 20 20 114 www.lutherstadt-wittenberg.de Altstadtbahn und Elbeschifffahrt 12 . Veranstaltungstipps 13 – 17 ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN UNSER SERVICE FÜR SIE: . TOURIST-INFORMATIONEN Kostenlose Beratung zu Aufenthalten, Aktivitäten und Angeboten in der Lutherstadt Veranstaltungen Clack-Theater 18 – 21 • am Schlossplatz . Wittenberg und in der umliegenden Region 01. September – 05. November Veranstaltungstermine 22 – 33 Zusendung von Informationsmaterial . täglich 9.00 – 18.00 Uhr kostenloser Online-Newsletter Wissenswert | Souvenirtipp 34 – 35 06. November – 31. Dezember . Vermittlung von Hotels, Pensionen, Mo – Fr 10.00 – 16.00 Uhr Ferienhäusern und Ferienwohnungen Weihnachtszauber 36 – 37 . Sa/So/FT: 10.00 – 14.00 Uhr Gruppenangebote/-reservierungen 1. und 2. Weihnachtsfeiertag geschlossen Pauschalangebote/Online-Buchung Ausstellungen 38 . Außerhalb der Öffnungszeiten stehen wir Ihnen und -Anfrage Veranstaltungtipp | Highlights 2018 39 von Mo – Fr von 8.00 bis 20.00 Uhr unter der Ausflugstipps für Lutherstadt Wittenberg . kostenlosen Urlaubshotline 0800 20 20 114 und die umliegende Region Shoppingerlebnis 40 zur Verfügung. Stadt- und Eventführungen .