PRIMARY SOURCE Two Papal Bulls of 6 March 1255, Issued By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Invasions, Insurgency and Interventions: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark 1654 - 1658. A Dissertation Presented by Christopher Adam Gennari to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Christopher Adam Gennari 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Christopher Adam Gennari We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Ian Roxborough – Dissertation Advisor, Professor, Department of Sociology. Michael Barnhart - Chairperson of Defense, Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of History. Gary Marker, Professor, Department of History. Alix Cooper, Associate Professor, Department of History. Daniel Levy, Department of Sociology, SUNY Stony Brook. This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School """"""""" """"""""""Lawrence Martin "" """""""Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Invasions, Insurgency and Intervention: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark. by Christopher Adam Gennari Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 "In 1655 Sweden was the premier military power in northern Europe. When Sweden invaded Poland, in June 1655, it went to war with an army which reflected not only the state’s military and cultural strengths but also its fiscal weaknesses. During 1655 the Swedes won great successes in Poland and captured most of the country. But a series of military decisions transformed the Swedish army from a concentrated, combined-arms force into a mobile but widely dispersed force. -

Euromosaic III Touches Upon Vital Interests of Individuals and Their Living Conditions

Research Centre on Multilingualism at the KU Brussel E U R O M O S A I C III Presence of Regional and Minority Language Groups in the New Member States * * * * * C O N T E N T S Preface INTRODUCTION 1. Methodology 1.1 Data sources 5 1.2 Structure 5 1.3 Inclusion of languages 6 1.4 Working languages and translation 7 2. Regional or Minority Languages in the New Member States 2.1 Linguistic overview 8 2.2 Statistic and language use 9 2.3 Historical and geographical aspects 11 2.4 Statehood and beyond 12 INDIVIDUAL REPORTS Cyprus Country profile and languages 16 Bibliography 28 The Czech Republic Country profile 30 German 37 Polish 44 Romani 51 Slovak 59 Other languages 65 Bibliography 73 Estonia Country profile 79 Russian 88 Other languages 99 Bibliography 108 Hungary Country profile 111 Croatian 127 German 132 Romani 138 Romanian 143 Serbian 148 Slovak 152 Slovenian 156 Other languages 160 Bibliography 164 i Latvia Country profile 167 Belorussian 176 Polish 180 Russian 184 Ukrainian 189 Other languages 193 Bibliography 198 Lithuania Country profile 200 Polish 207 Russian 212 Other languages 217 Bibliography 225 Malta Country profile and linguistic situation 227 Poland Country profile 237 Belorussian 244 German 248 Kashubian 255 Lithuanian 261 Ruthenian/Lemkish 264 Ukrainian 268 Other languages 273 Bibliography 277 Slovakia Country profile 278 German 285 Hungarian 290 Romani 298 Other languages 305 Bibliography 313 Slovenia Country profile 316 Hungarian 323 Italian 328 Romani 334 Other languages 337 Bibliography 339 ii PREFACE i The European Union has been called the “modern Babel”, a statement that bears witness to the multitude of languages and cultures whose number has remarkably increased after the enlargement of the Union in May of 2004. -

The Triumphant Genealogical Awareness of the Nobility In

LITHUANIAN HISTORICAL STUDIES 22 2018 ISSN 1392-2343 PP. 29–49 THE TRIUMPHANT GENEALOGICAL AWARENESS OF THE NOBILITY IN THE GRAND DUCHY OF LITHUANIA IN THE 17TH AND 18TH CENTURIES Agnė Railaitė-Bardė (Lithuanian Institute of History) ABSTRACT This article attempts to show how the manifestation of ancestors was expressed in the genealogical awareness of the nobility in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, using publications to mark special occasions in the 17th and 18th centuries, genealogical trees and diagrams. The research seeks to establish what effect the exaltation of various battles had on the genealogical memory of the nobility in the Grand Duchy, bearing in mind the context of its involvement in one of the most famous battles it ever fought. The genealogical sources mentioned were examined in order to ascertain which battles and what memories of the commanders who fought in them were important to the genealogical awareness of the nobility, and why this memory was selective, for some battles and notable heroes from these battles are remembered and glorified, while others are simply forgotten. Memories of which battles were important to the genealogical presentation of certain families, how was it expressed, and in what period were the ancestors who participated in these battles remembered? The first part of the study presents the memory of ancestors as soldiers, and the ways this memory was expressed. The second part focuses on an- cestors who distinguished themselves in specific battles, and which family members who participated in battles are remembered and honoured, in this way distinguishing them from other ancestors. KEYWORDS: Grand Duchy of Lithuania; nobility; genealogical awareness; militaristic; heraldry. -

BORDERLANDS of WESTERN CIVILIZATION a His Tory of East

BORDERLANDS OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION A His tory of East Cen tral Eu rope by OSCAR HALECKI Second Edition Edited by Andrew L. Simon Copyright © by Tadeusz Tchorzewski , 1980. ISBN: 0-9665734-8-X Library of Congress Card Number: 00-104381 All Rights Reserved. The text of this publication or any part thereof may not he reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by Simon Publications, P.O. Box 321, Safety Harbor, FL 34695 Printed by Lightning Source, Inc. La Vergne , TN 37086 Con tents PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION 1 PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION 4 1 THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND ETHNOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND 9 2 THE SLAVS AND THEIR NEIGHBORS 19 3 TOWARD POLITICAL ORGANIZATION 33 4 THE HERITAGE OF THE TENTH CENTURY 51 5 INTERNAL DISINTEGRATION AND FOREIGN PENETRATION 67 THE REPERCUSSIONS OF THE FOURTH CRUSADE IN THE BALKANS 77 6 THE HERITAGE OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY 93 7 THE NEW FORCES OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY 107 8 THE TIMES OF WLADYSLAW JAGIELLO AND SIGISMUND OF LUXEMBURG 135 9 THE LATER FIFTEENTH CENTURY 151 10 FROM THE FIRST CONGRESS OF VIENNA TO THE UNION OF LUBLIN 167 11 THE LATER SIXTEENTH CENTURY THE STRUGGLE FOR THE DOMINIUM MARIS BALTICI 197 12 THE FIRST HALF OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY 219 13 THE SECOND HALF OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY 239 14 THE END OF THE ANCIEN REGIME 261 15 THE PARTITIONS OF POLAND AND THE EASTERN QUESTION 289 16 THE NAPOLEONIC PERIOD 309 17 REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS UNTIL 1848 325 18 FROM THE CRIMEAN WAR TO THE CONGRESS OF BERLIN 353 19 TOWARD WORLD WAR I 373 20 THE CONSEQUENCES OF WORLD WAR I 395 21 THE PEOPLES OF EAST CENTRAL EUROPE BETWEEN THE WARS 417 22 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BETWEEN THE WARS 457 23 HITLER’S WAR 479 24 STALIN’S PEACE 499 BIBLIOGRAPHY 519 INDEX 537 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION Polish born Oscar Halecki (1891 - 1973) was Professor of History at Cracow and Warsaw universities between the two world wars. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

HFA Fine Art 09Fev2020 Combine All 3.Indd

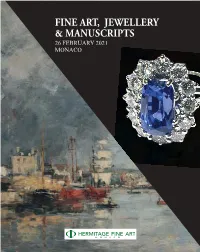

FINE ART, JEWELLERY & MANUSCRIPTS 26 FEBRUARY 2021 MONACO HERMITAGE FINE ART TEAM AUCTIONEER & EXPERTS PAR LE MINISTERE DE MAITRE CLAIRE NOTARI HUISSIER DE JUSTICE A MONACO FINE ART, JEWELLERY & MANUSCRIPTS Elena Efremova Anna Chouamier Stephen Cristea Evgenia Lapshina Sergey Podstanitsky Director Deputy Director Auctioneer Expert Specially Invited Manuscripts & Expert Russian rare Books (Moscow) paintings RUSSIAN ART & HISTORY FEBRUARY 25, 2021 - 10.00 FINE ART & JEWELLERY MANUSCRIPTS Yolanda Lopez Maria Lorena Elisa Passaretti Hélène Foutermann Stéphane Pepe Administrator Franchi Auction assistant Jewellery Expert Furniture and Work Public Relations of art, XXVII - XIX FEBRUARY 26, 2021 - 10.00 Manager Lots: 611, 612, 613, 614, 615, 616, 619 PREVIEW BY APPOINTMENT Hermitage Fine Art would like to express its Catalogue Design: Contact : gratitude to Igor Kouznetsov for his support Camille Maréchaux Tel: +377 97773980 with IT. Fax: +377 97971205 Photography: All lots marked with the symbol + are under François Fernandez info@hermitagefi neart.com temporary importation and are subject to import Eric Teisseire tax (EU) Sun Offi ce Business Center - 5 bis Avenue Saint-Roman, Monaco Maxime Melnikov Cataloguing notes: Yolanda Lopez Elisa Passaretti Scan QR for online catalogue Enquiries - tel: +377 97773980 - Email: info@hermitagefi neart.com TRANSPORTATION LIVE AUCTION WITH 25, Avenue de la Costa - 98000 Monaco Tel: +377 97773980 www.hermitagefi neart.com Between the 16th and 17th centuries, Italy witnessed the flourishing painting art of the Bolognese School or the School of Bologna, rival to Florence and Rome. Pioneered by the Carracci family, this school merged together the solidity of High Renaissance painting and the rich colours of the Venetian school. -

Archivum Lithuanicum Indices

I S S N 1 3 9 2 - 7 3 7 X I S B N 3-447-09469-9 Archivum Lithuanicum Indices 1 2 Archivum Lithuanicum 7 KLAIPËDOS UNIVERSITETAS LIETUVIØ KALBOS INSTITUTAS ÐIAULIØ UNIVERSITETAS VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETAS VYTAUTO DIDÞIOJO UNIVERSITETAS ARCHIVUM Lithuanicum Indices HARRASSOWITZ VERLAG WIESBADEN 2005 3 Redaktoriø kolegija / Editorial Board: HABIL. DR. Giedrius Subaèius (filologija / philology), (vyriausiasis redaktorius / editor), UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT CHICAGO, LIETUVIØ KALBOS INSTITUTAS, VILNIUS DR. Ona Aleknavièienë (filologija / philology), LIETUVIØ KALBOS INSTITUTAS, VILNIUS HABIL. DR. Saulius Ambrazas (filologija / philology), LIETUVIØ KALBOS INSTITUTAS, VILNIUS DOC. DR. Roma Bonèkutë (filologija / philology), KLAIPËDOS UNIVERSITETAS PROF. DR. Pietro U. Dini (kalbotyra / linguistics), UNIVERSITÀ DI PISA DR. Jolanta Gelumbeckaitë (filologija / philology), HERZOG AUGUST BIBLIOTHEK, WOLFENBÜTTEL, LIETUVIØ KALBOS INSTITUTAS, VILNIUS DR. Birutë Kabaðinskaitë (filologija / philology), VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETAS PROF. HABIL. DR. Rûta Marcinkevièienë (filologija / philology), VYTAUTO DIDÞIOJO UNIVERSITETAS, KAUNAS DOC. DR. Bronius Maskuliûnas (filologija / philology), ÐIAULIØ UNIVERSITETAS DR. Jurgis Pakerys (filologija / philology), VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETAS, LIETUVIØ KALBOS INSTITUTAS, VILNIUS DR. Christiane Schiller (kalbotyra / linguistics), FRIEDRICH-ALEXANDER-UNIVERSITÄT ERLANGEN-NÜRNBERG PROF. DR. William R. Schmalstieg (kalbotyra / linguistics), PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY MGR. Mindaugas Ðinkûnas (kalbotyra / linguistics), LIETUVIØ KALBOS -

LITHUANIAN-AMERICAN NEWS JOURNAL $5 March 2015 This Month in History

LITHUANIAN-AMERICAN NEWS JOURNAL $5 March 2015 this month in history March Anniversaries 760 yeas ago 110 years ago March 6, 1255 March 12, 1905 King Mindaugas, who had been crowned in 1253, obtained the Birth of Fr. Alfonsas Lipniūnas in Talkonys. Lipniūnas was ordained permission of Pope Alexander IV to crown his son as king of Lithu- in 1930, taught sociology and theology in Panvežys and Vilnius, ania, to ensure continuity of the dynasty and prevent interference and was named director of youth for the country. Famed for his from the Livonian Order. However, both Mindaugas and two of sermons during the time of German occupation, he founded his sons were assassinated in 1263 by his nephew Treniota and the Lithuanian Foundation to aid Lithuanians, Poles and Jews. rival Duke Daumantas. Treniota became the next ruler of Lithuania. Because of his activities, which included urging young people to resist conscription into the German army, he was imprisoned in Stutthof Concentration Camp in 1943, where he still celebrated 575 years ago mass daily. He died shortly after being liberated. March 20, 1440 Grand Duke Žygimantas Kęstutaitis was assassinated in Trakai by supporters of former Grand Duke Švitrigaila. The youngest son of 85 years ago Grand Duke Kęstutis and Birutė, Žygimantas ruled from 1432, after March 10, 1930 signing the Union of Grodno with Jogaila and ceding territories in Lithuanian playwright and poet Justinas Volhynia and Podolia to Poland. Marcinkevičius was born in Važatkiemis. Known as “the poet of the people” during the Soviet occupation, he developed a humanistic, roman- 160 years ago tic and lyric style, diverging from the heroic and March 17, 1855 propagandistic style of socialist realism. -

HARVARD UKRAINIAN STUDIES Volume X Number 3/4 December 1986

HARVARD UKRAINIAN STUDIES Volume X Number 3/4 December 1986 Concepts of Nationhood in Early Modern Eastern Europe Edited by IVO BANAC and FRANK E. SYSYN with the assistance of Uliana M. Pasicznyk Ukrainian Research Institute Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts Publication of this issue has been subsidized by the J. Kurdydyk Trust of the Ukrainian Studies Fund, Inc. and the American Council of Learned Societies The editors assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion made by contributors. Copyright 1987, by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved ISSN 0363-5570 Published by the Ukrainian Research Institute of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. Typography by the Computer Based Laboratory, Harvard University, and Chiron, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts. Printed by Cushing-Malloy Lithographers, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction, by Ivo Banac and Frank E. Sysyn 271 Kiev and All of Rus': The Fate of a Sacral Idea 279 OMELJAN PRITSAK The National Idea in Lithuania from the 16th to the First Half of the 19th Century: The Problem of Cultural-Linguistic Differentiation 301 JERZY OCHMAŃSKI Polish National Consciousness in the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century 316 JANUSZ TAZBIR Orthodox Slavic Heritage and National Consciousness: Aspects of the East Slavic and South Slavic National Revivals 336 HARVEY GOLDBLATT The Formation of a National Consciousness in Early Modern Russia 355 PAUL BUSHKOVITCH The National Consciousness of Ukrainian Nobles and Cossacks from the End of the Sixteenth to the Mid-Seventeenth Century 377 TERESA CHYNCZEWSKA-HENNEL Concepts of Nationhood in Ukrainian History Writing, 1620 -1690 393 FRANK E. -

THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi The Latin New Testament A Guide to its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts H.A.G. HOUGHTON 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/2/2017, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © H.A.G. Houghton 2016 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and unless otherwise stated distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution –Non Commercial –No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2015946703 ISBN 978–0–19–874473–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

The Evolution of Strategy

This page intentionally left blank The Evolution of Strategy Is there a ‘Western way of war’ which pursues battles of annihilation and single-minded military victory? Is warfare on a path to ever greater destructive force? This magisterial new account answers these questions by tracing the history of Western thinking about strategy – the employ- ment of military force as a political instrument – from antiquity to the present day. Assessing sources from Vegetius to contemporary America, and with a particular focus on strategy since the Napoleonic Wars, Beatrice Heuser explores the evolution of strategic thought, the social institutions, norms and patterns of behaviour within which it operates, the policies that guide it and the culture that influences it. Ranging across technology and warfare, total warfare and small wars as well as land, sea, air and nuclear warfare, she demonstrates that warfare and strategic thinking have fluctuated wildly in their aims, intensity, limitations and excesses over the past two millennia. beatrice heuser holds the Chair of International History at the School of Politics and International Relations, University of Reading. Her publications include Reading Clausewitz (2002); Nuclear Mentalities? (1998) and Nuclear Strategies and Forces for Europe, 1949-2000 (1997), both on nuclear issues in NATO as a whole, and Britain, France, and Germany in particular. The Evolution of Strategy Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present Beatrice Heuser cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521155243 © Beatrice Heuser 2010 This publication is in copyright. -

The Monarchy in Lithuania History, Rights and Prospects

Carmelo Curró Troiano The Monarchy in Lithuania History, Rights and Prospects Presentation and modified by Salvatore Ferdinando Antonio Caputo Page 1 of 15 BRIEF HISTORY – SALVATORE FERDINANDO ANTONIO CAPUTO First known habitation of Lithuania dates back to the final ice age, 10 000 BC. The hunter’s gatherers were slowly replaced by farmers. The origin of Baltic tribes in the area is disputed but it probably dates to 2500 BC. These forefathers of Lithuanians were outside the main migration routes and thus are among the oldest European ethnicities to have settled in approximately current area. The word “Lithuania” was mentioned for the first time in the annals of Quedlinburg (year 1009) where a story describes how Saint Bruno was killed by the pagans “on the border of Lithuania and Russ”. These Baltic peoples traded amber with Romans and then fought Vikings. In the era only one small tribe from area around Vilnius was known as Lithuanians but it was this tribe that consolidated the majority of other Baltic tribes. This process accelerated under king Mindaugas (ca. 1200– 12 September 1263) who became a Christian and received a crown from the Pope in 1253. Mindaugas was the first and only crowned king of Lithuania. In the early 13th century, Lithuania was inhabited by various pagan Baltic tribes, which began to organize themselves into a state – the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. By the 1230s, Mindaugas emerged as the leader of the Grand Duchy. In 1249, an internal war erupted between Mindaugas and his nephews Tautvilas and Edivydas. As each side searched for foreign allies, Mindaugas succeeded in convincing the Livonian Order not only to provide military assistance, but also to secure for him the royal crown of Lithuania in exchange for his conversion to Catholicism and some lands in western Lithuania.