Enabling Residents of Lebanon to Purify Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Sanitation Resource Recovery Products & Technologies

Guide to Sanitation Resource Recovery Products & Technologies A supplement to the Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies 1st Edition Guide to Sanitation Resource Recovery Products & Technologies A supplement to the Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies Jennifer McConville, Charles Niwagaba, Annika Nordin, Marcus Ahlström, Vivian Namboozo and Mark Kiffe We would like to thank the following individuals and their organisations/ institutions for their invaluable contributions to this publication: Allan Komakech (Makerere University), Åke Nordberg (SLU), Amadou Gueye (Delvic Sanitation Initiatives), Arne Panesar (GIZ), Barbara Jeanne Ward (Eawag), Bastian Etter (VUNA), Björn Vinnerås (SLU), Christian Zurbrügg (Eawag/SLU), Christoph Lüthi (Eawag), Cecilia Lalander (SLU), Daniel Ddiba (SEI), Dorothee Sphuler (Eawag), Ebenezer Soh Kengne (University of Bamenda), Elhadji Mamadou Sonko (Cheikh Anta Diop University), Elisabeth Kvarnström (RISE), Ershad Ulla Khan (SLU), Eva Thorin (Mälardalen University), Grietje Zeeman (Wageningen University & Research), Håkan Jönsson (SLU), Jenna Senecal (SLU), Kim Andersson (SEI), Linda Strande (Eawag), Linus Dagerskog (SEI), Luis Perez Mercado (SLU), Lukas Ulrich (Eawag), Madeleine Fogde (SEI), Melissa A. Barton, Naomi Korir (Sanivation), Peter Morgan, Priscila de Morais Lima (SLU), Prithvi Simha (SLU), Robert Gensch (German Toilet Organisation), and Sahar Dalahmeh (Uppsala University). We would like to acknowledge support from: The Swedish Research Council (grant number: 2016-06297) and -

Part 3: Toilet Design Considerations: Micro Level

PLANNING FOR PUBLIC TOILETS PART 3: MICRO LEVEL: TOILET DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS: Inclusive Design for Different Types of User Groups ' To a good doctor there is no physical or mental aspect of his patient which should embarrass him. He may be worried or shocked by what his diagnosis reveals, but if he's any good, he is not embarrassed. Correspondingly, therefore, there should be no type of building, and no human function related to it which should embarrass the architect!' (Architects Journal, 1953, No.117). This section looks at the 'micro' level of detailed toilet design. However, the emphasis is upon principles, and upon 'seeing' how the different components of the toilet cubicle 'work' together, because, as they say, 'the devil is in the detail'. The emphasis is again upon the user, the range of user types, and the social and qualitative factors involved, rather than upon the technical plumbing and engineering aspects dealt with elsewhere in this course programme. There is also a longer optional explanation of the issues in the second part of the paper. A PowerPoint accompanies and illustrates Part 3. Part 3 is longer because detailed issues are so important. A fuller bibliography, list of references is given at the end. In fact Part 3 may be used as a module in its own right on inclusive design. People are Important There are many detailed design guides on the precise dimensions and locations of rails, toilet pans, washbasins, mirrors etc and so it is not the purpose of this chapter to give precise guidance on these. 'The problem' is that some toilet manuals deal with each component without seeing how they inter-relate with each other spatially. -

Nose-To-Tail

From Nose to Tail Lessons to Inspire Care and Compassion for Dogs Grades: 3-5 Dear Educator, Thank you for taking the first step to foster a culture of kindness among your grade 3-5 students with From Nose to Tail: Lessons to Inspire Care and Compassion for Dogs. Following a successful pilot program, we are pleased to offer this exciting humane curriculum on a wider basis. Please find enclosed: ɠ A Home for Dakota ɠ Maggie’s Second Chance ɠ From Nose to Tail: Lessons to Inspire Care and Compassion for Dogs, Grades 3-5 From Nose to Tail was designed by teachers for independent use by formal and informal educators. The curriculum is age-appropriate, engaging and flexible—lessons may be spaced over a period of days or weeks. We recommend that the lessons be scaffolded and followed in order—however, they can stand on their own. From Nose to Tail features: ɠ Alignment with National Education and Common Core standards in science, math, language arts, health and social studies; ɠ Five lesson plans, each requiring approximately 40 to 60+ minutes of class time; ɠ A Home for Dakota, the award-winning story of a rescued puppy mill breeding dog; ɠ Maggie’s Second Chance (Gr. 3-5) or Buddy Unchained (K-Gr. 2); ɠ Character education concepts such as compassion, responsibility and empathy; ɠ Service-learning projects aimed at helping puppy mill dogs and encouraging self-efficacy and good citizenship. Importantly, From Nose to Tail advances both humane and academic learning objectives, so it can be readily incorporated into general classroom instruction. -

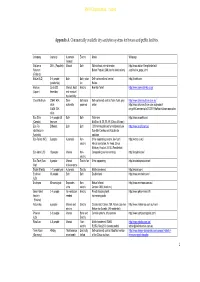

RMIT Classification: Trusted

RMIT Classification: Trusted Appendix A. Commercially available dry sanitation systems for houses and public facilities. Company Capacity Automatic Electric Model Webpage /manual BioLan or 200 L (Populett) Manual Both With/without urine diversion http://www.biolan.fi/english/default Naturum Biolan Populett 200 (tourist destinations) .asp?active_page_id=1 (Finland) BioLet (US) 3–4 people Both Both, solar Self-contained and central http://biolet.com (residential) fan Ez-loo Bio-Lux Up to 200 Manual, heat Electric Eco-Bio Toilet http://www.seiwa-denko.co.jp/ (Japan) times/day and sawdust by electricity Clivus Multrum CM40: 40K Semi- Both/solar Self-contained, central, foam flush, grey http://www.clivusmultrum.com.au/ visits automatic powered water http://www.clivusmultrum.com.au/product- CM20: 20K range#!/Commercial/c/20728119/offset=0&sort=nameAsc visits Eco Ethic 3–4 people full Both Both Waterless http://www.ecoethic.ca/ (Canada) time use MullToa 10, 25, 55, 65 (Clivus Multrum) Eco Flo Different Both Both Different models but for residential use http://www.ecoflo.net.au/ (distributor in Sun-Mar Centrex and Kazuba for Australia) outdoors Eco Toilets (NZ) 5 people Automatic Non- Urine separating, central, low flush: http://wctnz.co.nz/ electric African sanitation, Air head, Clivus Multrum, Eco Let 240 XL(Residential) Eco John (US) 10 people Manual Non- Composting and incinerating http://ecojohn.com/ electric Eco Tech (Sun 6 people Manual Electric fan Urine separating http://ecotechproducts.net/ Mar) A few months Ekolet (Finish) 1–7 people/year -

Big Girl, Small Town a Novel Michelle Gallen

Big Girl, Small Town a novel Michelle Gallen ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2020 For Mehdi, who sees clearly What if we accept these points of light, their translucence, their brightness; what if we let ourselves enjoy this, stop fearing it, get used to it; what if we come to believe in it, to expect it, to be impressed upon by it; what if we take hope and forgo our ancient heritage and instead, and infused, begin to entrain with it, with ourselves then to radiate it; what if we do that, get educated up to that, and then, just like that, the light goes off or is snatched away? Milkman, Anna Burns Contents Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Acknowledgments About the Author Majella kept a list of stuff in her head that she wasn’t keen on. Her top ten hadn’t changed in seven years: 1) Small talk, bullshit, and gossip 2) Physical contact 3) Noise 4) Bright lights 5) Scented stuff 6) Cunter 7) Sweating 8) Jokes 9) Make-up 10) Fashion The full list of things Majella wasn’t keen on extended to ninety-seven items, with subcategories for each item. For example, make-up included nail polish, lipstick, foundation, mascara etc., and Majella had further itemized each subcategory: Item 9.1: Make-up: Nail polish • Is too heavy—weighing fingers down. • Looks utterly unnatural when colored—e.g., red, orange, black —giving people the appearance of wearing beetle carapaces on their finger ends. • Difficult to apply, requiring practice, time and skill. • Prone to smudging during drying period. -

Compendium of Sanitation Technologies in Emergencies

Compendium 1st Edition of Sanitation Technologies in Emergencies Compendium 1st Edition of Sanitation Technologies in Emergencies Robert Gensch (GTO), Amy Jennings (BORDA), Samuel Renggli (Eawag), Philippe Reymond (Eawag) We would like to thank the following individuals and their organisations/institutions for their invaluable contributions to this publication: Djilali Abdelghafour, Nienke Andriessen, Leonellha Barreto-Dillon, Andy Bastable, Magdalena Bäuerl, Benjamin Bernan- dino, Damian Blanc, Franck Bouvet, Patrick Bracken, Chris Buckley, Marc-Andre Bünzli, Chris Canaday, Daniel Clauss, Benjamin Dard, Malcolm Dickson, Paul Donahue, Georg Ecker, Miriam Englund, Marta Fernández Cortés, Suzanne Ferron, Claire Furlong, Sergio Gelli, Feline Gerstenberg, Moritz Gold, Celia González Otálora, Peter Harvey, Oliver Hoffmann, Tineke Hooijmans, Andrews Jacobs, Heidi Johnston, Christopher Kellner, Anthony Kilbride, Sasha Kramer, Jenny Lamb, Günther Langergraber, Anne Lloyd, Andreas Ludwig, Christoph Lüthi, Saskia Machel, Grover Mamani, Adeline Mertenat, Mona Mijthab, Alexander Miller, Patrice Moix, Paolo Monaco, Bella Monse, Hans-Joachim Mosler, Burt Murray, Arne Pane sar, Thilo Panzerbieter, Jonathan Parkinson, Dominique Porteaud, Nick Preneta, Torsten Reckerzügl, Bob Reed, Stefan Reuter, Romain Revol, Nina Röttgers, Johannes Rück, Vasco Schelbert, Jan-Christoph Schlenk, Jan-Hendrik Schmidt, Stephanie Schramm, Jan Spit, Haakon Spriewald, Steve Sugden, Annkatrin Tempel, Elisabeth Tilley, Erika Trabucco, Tobias Ulbrich, Lukas Ulrich, Claudio Valsangiacomo, -

Business Models for Fecal Sludge Management in India

RESOURCE RECOVERY & REUSE SERIES 18 (SPECIAL ISSUE) ISSN 2478-0529 Business Models for Fecal Sludge 18 Management in India Krishna C. Rao, Sasanka Velidandla, Cecilia L. Scott and Pay Drechsel About the Resource Recovery & Reuse Series Resource Recovery and Reuse (RRR) is a subprogram of the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE) dedicated to applied research on the safe recovery of water, nutrients and energy from domestic and agro-industrial waste streams. This subprogram aims to create impact through different lines of action research, including (i) developing and testing scalable RRR business models, (ii) assessing and mitigating risks from RRR for public health and the environment, (iii) supporting public and private entities with innovative approaches for the safe reuse of wastewater and organic waste, and (iv) improving rural-urban linkages and resource allocations while minimizing the negative urban footprint on the peri-urban environment. This subprogram works closely with the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), United Nations University (UNU), and many national and international partners across the globe. The RRR series of documents present summaries and reviews of the subprogram’s research and resulting application guidelines, targeting development experts and others in the research for development continuum. RESOURCE RECOVERY & REUSE SERIES 18 (SPECIAL ISSUE) Business Models for Fecal Sludge Management -

An Integrative Action for Metabolomic Analyses in Human Nutritional

REVIEW Nutritional Metabolomics Nutritional metabolomics (nu- trimetabolomics) requires a trans- M. M. Ulaszewska, C. H. Weinert, A. disciplinary effort spanning the fields Trimigno, R. Portmann, C. Andres of food science, human nutrition, ana- Lacueva, R. Badertscher, L. Brennan, lytical chemistry, and bioinformatics. C. Brunius, A. Bub, F. Capozzi, M. Ciali`e Rosso, C. E. Cordero, H. Daniel, S. Durand, B. Egert, P. G. Ferrario, E. J. M. Feskens, P. Franceschi, M. Garcia-Aloy, F. Giacomoni, P. Giesbertz, R. Gonz´alez-Dom´ınguez, K. Hanhineva, L. Y. Hemeryck, J. Kopka, S. E. Kulling, R. Llorach, C. Manach, F. Mattivi, C. Mign´e, L. H. Munger,¨ B. Ott, G. Picone, G. Pimentel, E. Pujos-Guillot, S. Riccadonna, M. J. Rist, C. Rombouts, J. Rubert, T. Skurk, P. S. C. Sri Harsha, L.Van Meulebroek, L. Vanhaecke, R. V´azquez-Fresno, D. Wishart, G. Verg`eres* . 1800384 Nutrimetabolomics: An Integrative Action for Metabolomic Analyses in Human Nutritional Studies REVIEW Nutritional Metabolomics www.mnf-journal.com Nutrimetabolomics: An Integrative Action for Metabolomic Analyses in Human Nutritional Studies Marynka M. Ulaszewska, Christoph H. Weinert, Alessia Trimigno, Reto Portmann, Cristina Andres Lacueva, Ren´e Badertscher, Lorraine Brennan, Carl Brunius, Achim Bub, Francesco Capozzi, Marta Ciali`e Rosso, Chiara E. Cordero, Hannelore Daniel, St´ephanie Durand, Bjoern Egert, Paola G. Ferrario, Edith J.M. Feskens, Pietro Franceschi, Mar Garcia-Aloy, Franck Giacomoni, Pieter Giesbertz, Raul´ Gonzalez-Dom´ ´ınguez, Kati Hanhineva, Lieselot Y. Hemeryck, Joachim Kopka, Sabine E. Kulling, Rafael Llorach, Claudine Manach, Fulvio Mattivi, Carole Mign´e, Linda H. Munger,¨ Beate Ott, Gianfranco Picone, Gr´egory Pimentel, Estelle Pujos-Guillot, Samantha Riccadonna, Manuela J. -

Kuivakäymälät Ja Harmaiden Vesien Käsittely Dry Toilets and Grey Water Treatment

Kuivakäymälät ja harmaiden vesien käsittely Dry Toilets and Grey Water Treatment KÄYMÄLÄSEURA HUUSSI RY GLOBAL DRY TOILET ASSOCIATION OF FINLAND 1 SISÄLLYS CONTENTS Käymäläseura Huussi ry ...............2 Global Dry Toilet Association of Finland ....................................2 Käymäläseura Huussi ry:n hankkeet .....................................3 KÄYMÄLÄSEURA HUUSSI RY Projects .......................................3 GLOBAL DRY TOILET ASSOCIATION OF FINLAND Kuivakäymälä ratkaisuna asumiseen ja mökille ...................4 Dry toilet as a solution .................4 KÄYMÄLÄSEURA HUUSSI RY GLOBAL DRY TOILET Kootut ohjeet ja vinkit .................5 ASSOCIATION OF FINLAND Instructions ................................5 Käymäläseura Huussi ry on Pesuvesien käsittelyjärjestelmä vuonna 2002 perustettu kansa- The Global Dry Toilet valitaan tarpeen mukaan .............6 laisjärjestö, jonka toimipaikka Association of Finland is a Grey water treatment system on Tampere, mutta toimialuee- non-governmental organiza- chosen based on needs ...............6 na koko maailma. Yhdistyksel- tion established in 2002. Kestävän kehityksen tavoite 6: lä on henkilö-, yritys- ja yhtei- The association is based in Puhdas vesi ja sanitaatio .............7 söjäseniä yhteensä noin 500. Tampere but our area of oper- Sustainable development goal 6: Clean water and sanitation ...........7 ation covers the whole world. hdistyksen kunnianhimoinen We have about 500 members, Stella Marketing Ky .....................8 visio on tehdä kuivakäymä- including company -

Improving Sanitation in Cold Regions Maryanne Leblanc and Robert A

WATER GLOBAL PRACTICE JUNE 2019 Improving Sanitation in Cold Regions Maryanne Leblanc and Robert A. Reed with William Kingdom, Catalog of Technical Options for Martin Gambrill, and Diego Juan Rodriguez Household-Level Sanitation About the Water Global Practice Launched in 2014, the Word Bank Group's Water Global Practice brings together nancing, knowledge, and implementation in one platform. By combining the Bank's global knowledge with country investments, this model generates more repower for transformational solutions to help countries grow sustainably. Please visit us at www.worldbank.org/water or follow us on Twitter @WorldBankWater. Improving Sanitation in Cold Regions: Catalog of Technical Options Disclaimer © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Acknowledgments This report is a product of the Water Global Practice. It was prepared by a team led by Diego J. Rodriguez (Senior Water Resources Management Specialist, Water Latin America and Caribbean, World Bank) and Martin P. -

Suomalaiset Kuivakaymalat.Pdf

Dry Toilets for every need Usually we realize the importance of found in regular waste water come from 2004. The regulation relates to wastewater functioning toilet only when there is none the water toilet. When dry toilet is used, treatment in the areas not connected to the to be found in the time of need. A working the remaining waste waters are much more public sewage and concerns approximately toilet is one of the basic needs for humans. easier to manage. one million Finnish people. By installing a dry Poor toilets and inadequate waste water toilet system, people can easily meet these treatment can lead to pollution of surface- Dry toilet doesn´t suffer from water shortages requirements. and groundwater reservoirs. However, it is or the freezing of water pipes and it is easy not necessary to use water to have modern to install. In addition a modern dry toilet has Dry toilets have developed from the early and hygienic toilet facilities. Dry toilet even less odours than a water toilet because days of plain pit latrines in outhouses. A part technology offers variety of choices from of the brilliant ventilation systems. The of this project is to present Finnish dry toilet summer cottages to stylish bathrooms. nutrients are safely returned to nutrient cycle manufacturers and their products. There are and they don´t add up to the eutrophication many models, each suited for a specifi c place Dry toilet of local water systems. For example the and use. Modern dry toilets are easy to • saves pure drinking water blue-green algae problems during summers maintain and comfortable to use. -

Onsite Wastewater Systems — Current Practices and a Proposed Basis for Evaluation

Reference Publi- cations NAT'L INST. OF l 81-2210 A111DS flTllSS Onsite Wastewater Systems — Current Practices and a Proposed Basis for Evaluation s> ////f March 1981 Fred Winter 'enter for Building Technology —QC *ational Engineering Laboratory 10Q .S. Department of Commerce ational Bureau of Standards , U56 Washington, DC 20234 81-2210 1981 national murkau 0» OTAKDARU8 LIBRARY JUL 2 0 1981 jno'i Clcc NBSIR 81-2210 *40 , US£> - * ONSITE WASTEWATER SYSTEMS CURRENT r * » 0 / rj PRACTICES AND A PROPOSED BASIS FOR mi EVALUATION Fred Winter Center for Building Technology National Engineering Laboratory U.S. Department of Commerce National Bureau of Standards Washington, DC 20234 March 1981 Prepared for Department of Housing and Urban Development Division of Energy, Building Technology and Standards Office Policy Development and Research Washington, DC 20410 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Malcolm Baldrige, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS, Ernest Ambler, Director »• i|T* ' ' ' , «* TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE iii ABSTRACT iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 3 2.1 Project Objectives 3 2.2 Project Scope 3 3. CLASSIFICATION OF ONSITE WASTEWATER ELEMENTS AND SYSTEMS 5 4. DOCUMENTATION OF THE ONSITE WASTEWATER SYSTEMS REVIEWED 8 5. ONSITE WASTEWATER SYSTEMS EVALUATION BASIS 30 5 . 1 Performance Criteria ....... 30 5.2 Classification of Site Conditions and Rating of Onsite Systems . 31 5.3 System Selection Based on Site Conditions 31 6 . REQUIREMENTS FOR DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS 40 7 . RECOMMENDATIONS ... 44 7.1 Recommendation of Wastewater Systems for Demonstration 44 7 . 2 Recommendation for Research 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY 50 REFERENCES 53 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued) Page APPENDIX 55 A.