Business Models for Fecal Sludge Management in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Combined Vermifiltration-Hydroponic System

applied sciences Article A Combined Vermifiltration-Hydroponic System for Swine Wastewater Treatment Kirill Ispolnov 1,*, Luis M. I. Aires 1,Nídia D. Lourenço 2 and Judite S. Vieira 1 1 Laboratory of Separation and Reaction Engineering-Laboratory of Catalysis and Materials (LSRE-LCM), School of Technology and Management (ESTG), Polytechnic Institute of Leiria, 2411-901 Leiria, Portugal; [email protected] (L.M.I.A.); [email protected] (J.S.V.) 2 Applied Molecular Biosciences Unit (UCIBIO)-REQUIMTE, Department of Chemistry, NOVA School of Science and Technology (FCT), NOVA University of Lisbon, 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Intensive swine farming causes strong local environmental impacts by generating ef- fluents rich in solids, organic matter, nitrogen, phosphorus, and pathogenic bacteria. Insufficient treatment of hog farm effluents has been reported for common technologies, and vermifiltration is considered a promising treatment alternative that, however, requires additional processes to remove nitrate and phosphorus. This work aimed to study the use of vermifiltration with a downstream hydroponic culture to treat hog farm effluents. A treatment system comprising a vermifilter and a downstream deep-water culture hydroponic unit was built. The treated effluent was reused to dilute raw wastewater. Electrical conductivity, pH, and changes in BOD5, ammonia, nitrite, nitrate, phosphorus, and coliform bacteria were assessed. Plants were monitored throughout the experiment. Electrical conductivity increased due to vermifiltration; pH stayed within a neutral to mild alkaline range. Vermifiltration removed 83% of BOD5, 99% of ammonia and nitrite, and increased nitrate by Citation: Ispolnov, K.; Aires, L.M.I.; 11%. -

Addressing Fecal Sludge Management in Rural Locations | Cambodia | Ideglobal.Org | Page 1

Addressing Fecal Sludge Management in Rural Locations | Cambodia | ideglobal.org | Page 1 TACTIC REPORT Addressing Fecal Sludge Management in Rural Locations Pit latrines have become the solution for rural sanitation in many of the world’s poorest, remote, and difficult to access locations. At some point in time, the pit fills. What can households in these areas do to safely manage their sanitation needs? Context As sanitation coverage increases across the globe, fecal sludge management (FSM) is becoming increasingly important as the next sanitation issue that needs to be addressed. Most FSM solutions are designed for urban environments and involve collection (by vacuum truck or manual emptying) and mass treatment (e.g., ponds, aerobic digesters). For rural communities and households in Cambodia, these solutions present both economic and logistical challenges. Households in some areas have been able to manage their pit emptying issues with the service of pump trucks that come directly to the household. However, these solutions are still relatively expensive, are sometimes unable to navigate rural roads, and many hand-made varieties of these trucks lack the ability to hygienically remove and transport waste. As motor-powered pumps are Addressing Fecal Sludge Management in Rural Locations | Cambodia | ideglobal.org | Page 2 becoming cheaper, households are increasingly opting to use these over manual emptying with buckets. Yet despite increasing availability of pumps and trucks, waste disposal is rarely handled safely. In rural areas, the cost of constructing and maintaining a safe, hygienic treatment collection plant is prohibitive. The economies of scale that enable mass waste treatment plants to operate sustainably in urban areas are simply not available in rural villages. -

Islanding Scheme Covering Bengaluru Metropolitan Area

Southern Regional Power Committee Bengaluru Minutes of the Meeting to deliberate on Islanding Scheme for Bangalore, held on 16.02.2021 through WebEx. A meeting to discuss formation of Islanding Scheme for Bangalore was held on 16.02.2021 under the chairmanship of Member Secretary (MS), SRPC in on-line mode though WebEx. The list of participants is attached at Annexure-I. 2. MS, SRPC welcomed all the participants to the meeting. He informed the forum that in the meeting held on 28.12.2020, to review Islanding Schemes in the country, Hon’ble Minister of State (IC) for Power and New & Renewable Energy, Government of India directed that Islanding Schemes should be designed for all major cities of the country, including Bangalore. Accordingly, SRPC was directed to take steps for devising an Islanding scheme covering Bangalore area. Member Secretary pointed out that absence of embedded generation has been a major drawback to have islanding scheme in Bangalore. However, considering the economy-driving aspects of Bangalore, like IT sector, Medical companies, Laboratories, Defence installations, and metro rail, etc., it is sensible to design and put in place an apt Islanding scheme for Bangalore area so that all its major loads can be guaranteed to remain immune to external grid failures. 3. Then, Superintending Engineer (P&SS), SRPC presented the philosophy adopted in identifying the Islanding Schemes that are under operation in Southern Region (SR), and detailed the guidelines being followed to form Islanding. The salient aspects, as given under, were explained: Approved Islanding Schemes in southern region are non-adaptive in nature. -

List of Municipalities Sl.No

LIST OF MUNICIPAL BODIES WHERE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD IN THE MIDDLE OF 2010 SL.NO. DISTRICT NAME OF MUNICIPALITY 1 Cooch Behar Municipality 2 Tufanganj Municipality Cooch Behar 3 Dinhata Municipality 4 Mathabhanga Municipality 5 Jalpaiguri Jalpaiguri Municipality 6 English Bazar Municipality Malda 7 Old Malda Municipality 8 Murshidabad Municipality 9 Jiaganj-Azimganj Municipality 10 Kandi Municipality Murshidabad 11 Jangipur Municipality 12 Dhulian Municipality 13 Beldanga Municipality 14 Nabadwip Municipality 15 Santipur Municipality 16 Ranaghat Municipality 17Nadia Birnagar Municipality 18 Kalyani Municipality 19 Gayeshpur Municipality 20 Taherpur Municipality 21 Kanchrapara Municipality 22 Halishar Municipality 23 Naihati Municipality 24 Bhatpara Municipality 25North 24-Parganas Garulia Municipality 26 North Barrackkpore Municipality 27 Barrackpore Municipality 28 Titagarh Municipality 29 Khardah Municipality \\Mc-4\D\Munc. Elec-2010\LIST OF MUNICIPALITIES SL.NO. DISTRICT NAME OF MUNICIPALITY 30 Kamarhati Municipality 31 Baranagar Municipality 32 North Dum Dum Municipality 33 Bongaon Municipality 34 Gobardanga Municipality 35North 24-Parganas Barasat Municipality 36 Baduria Municipality 37 Basirhat Municipality 38 Taki Municipality 39 New Barrackpore Municipality 40 Ashokenagar-Kalyangarh Municipality 41 Bidhannagar Municipality 42 Budge Budge Municipality 43South 24-Parganas Baruipur Municipality 44 Jaynagar-Mazilpur Municipality 45 Howrah Bally Municipality 46 Hooghly-Chinsurah Municipality 47 Bansberia Municipality 48 Serampore Municipality 49 Baidyabati Municipality 50 Champadany Municipality 51 Bhadreswar Municipality Hooghly 52 Rishra Municipality 53 Konnagar Municipality 54 Arambagh Municipality 55 Uttarpara Kotrung Municipality 56 Tarakeswar Municipality 57 Chandernagar Municipal Corporation 58 Tamluk Municipality Purba Medinipur 59 Contai Municipality 60 Chandrakona Municipality 61 Ramjibanpur Municipality 62Paschim Medinipur Khirpai Municipality 63 Kharar Municipality 64 Khargapur Municipality 65 Ghatal Municipality \\Mc-4\D\Munc. -

Vacuum Truck Standard Work Practice 1 Document

VACUUM TRUCK STANDARD WORK PRACTICE DOCUMENT INFORMATION Description Provides guidance for the safe operation and maintenance of Vac Truck equipment and describes methods for eliminating or reducing hazards and risks associated with vacuuming operations. Revision 2 Effective Date: September 24, 2018 Originator: Floyd Keller, Director EHS Approval: Dean Wallace, CEO TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE……………………………………………………………………………………..... 2 SCOPE…………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 RESPONSIBILITIES………….…………………………………………………………………. 2 PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT……………………………………………………. 2 PRE-OPERATIONAL PROCEDURES………………………………………………………. 3 OPERATING PROCEDURES………………………………………………………………… 4 HOSES AND CONTAINMENT…………………………………………………………………. 7 BONDING, GROUNDING AND VENTING……………………………………………………. 8 LIQUID VACUUM TRUCK SAFETY PROCEDURES……………………………………….. 9 MATERIAL CHARACTERISTICS AND HAZARDS………………………………………….. 9 LOADING AND OFF-LOADING SITE PREPARATION AND CONDITIONS……………... 9 VACUUM TRUCK OPERATOR REQUIREMENTS………………………………………….. 9 PORTABLE RAMP OFF-LOADING SAFETY PROCEDURES…………………………….. 10 COLLECTOR TANK OFF-LOADING………………………………………………………….. 10 WASH-OUT PROCEDURES……………………………………………………………………. 10 DOCUMENTATION………………………………………………………………………………. 11 CONTINUITY TESTING…………………………………………………………………………. 11 NATURE OF VACUUM TRUCK INJURIES…………………………………………………… 11 TRAINING…………………………………………………………………………………………. 12 1 VACUUM TRUCK STANDARD WORK PRACTICE 1. PURPOSE 1.1. To establish a procedure for safe operation of industrial vacuum loading equipment including personal protective equipment standards, -

Containment Zones of Hooghly

Hooghly District Containtment Areas [Category A] w.e.f 27th August , 2020 Annexure-1 Block/ Sl No. Sub Div GP/ Ward Police Station Containtment Area Zone A Municipality ENTIRE HOUSE OF KRISHNA CHOWDHURY INFRONT- SHOP-UMA TELECOM, BACK SIDE- ROAD, RIGHT SIDE:-RATION SHOP, LEFT SIDE:- SHOP-DURGA PHARMACY & Surrounding area of Zone A of ward no. 20 of Bansberia Municipality ,AC 193,PS 130 1 Sadar Bansberia Ward No. 20 MOGRA ENTIRE HOUSE OF PROTAB KAR ,IN FRONT- HOUSE OF AMMULYA CHAKRABORTY BACKSIDE- HOUSE OF BISHAL THAKUR RIGHT SIDE:HOUSE OF DR JAGANATH MAJUMDAR LEFT SIDE:- HOUSE OF DULAL BOSE & Surrounding area of Zone A of ward no. 20 of Bansberia Municipality ,AC 193,PS 130 Entire house of Bipradas Mukherjee,Chinsurah Station Road, Chinsurah, Hooghly, Surrounding area of house of Bipradas Mukherjee, East Side- H/O Biswadulal Chatterjee, West Side- Road , North Side- H/O Pranab Mukherjee, South Side- Pond Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra & Surrounding area of Zone A of Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra H/o ASHA BAG, Surrounding area of house of ASHA BAG, East Side- Balai Das West Side- Basu Mondal , North Side- Nidhir halder South Side- Nemai Mondal Sansad-VI, PS- 142 of Kodalia-I GP, Chinsurah-Mogra Block & Surrounding area of Zone A of Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra 2 Sadar Chinsurah-Mogra Kodalia-II Chinsurah A ZoneAnanda Appartment, 2nd Floor,whole Ananda Appartment Sansad-VI, PS- 142 of Kodalia-I GP, Chinsurah-Mogra Block & Surrounding area of Zone A of Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra H/O Alo Halder ,Surrounding area of house of ALO HALDER ., East Side- H/O Rina Hegde West Side-Vacant Land , North Side- H/O Sabita Biswas South Side- H/OJamuna Mohanti Sansad-VI, PS- 142of Kodalia-I GP, Chinsurah-Mogra Block & Surrounding area of Zone A of Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra Hooghly District Containtment Areas [Category A] w.e.f 27th August , 2020 Annexure-1 Block/ Sl No. -

M. Silvia Díaz Cruz Damià Barceló Editors

The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry 36 Series Editors: Damià Barceló · Andrey G. Kostianoy M. Silvia Díaz‐Cruz Damià Barceló Editors Personal Care Products in the Aquatic Environment The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry Founded by Otto Hutzinger Editors-in-Chief: Damia` Barcelo´ l Andrey G. Kostianoy Volume 36 Advisory Board: Jacob de Boer, Philippe Garrigues, Ji-Dong Gu, Kevin C. Jones, Thomas P. Knepper, Alice Newton, Donald L. Sparks More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/698 Personal Care Products in the Aquatic Environment Volume Editors: M. Silvia Dı´az‐Cruz Á Damia` Barcelo´ With contributions by A.G. Asimakopoulos Á M. Al Aukidy Á D. Barcelo´ Á M. Badia-Fabregat Á M.J. Bernot Á G. Caminal Á A. Chisvert Á M.M. de Oliveira e Sa´ Á K. Demeestere Á M. Di Carro Á M.S. Dı´az-Cruz Á J.C.G. Esteves da Silva Á P. Gago-Ferrero Á C. Ianni Á J.R. Justice Á K. Kannan Á M. Li Á M. Lv Á E. Magi Á M.S. Miranda Á D. Molins-Delgado Á S. Montesdeoca-Esponda Á I.N. Pasias Á B.R. Ramaswamy Á A. Salvador Á J.J. Santana-Rodrı´guez Á Z. Sosa-Ferrera Á Q. Sun Á S. Tanwar Á N.S. Thomaidis Á H. Van Langenhove Á T. Vega-Morales Á P. Verlicchi Á T. Vicent Á B. Yang Á G.-G. Ying Á C.-P. Yu Á E. Zambello Editors M. Silvia Dı´az‐Cruz Damia` Barcelo´ Department of Environmental Chemistry Department of Environmental Chemistry IDAEA-CSIC IDAEA-CSIC Barcelona Barcelona Spain Spain University of Girona ICRA Girona Spain ISSN 1867-979X ISSN 1616-864X (electronic) The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry ISBN 978-3-319-18808-9 ISBN 978-3-319-18809-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-18809-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015944206 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. -

List of Affiliated Colleges College Slno College Address Town District Phone 01 Phone 02 Email Code 1 6001 Govt

List of affiliated Colleges College Slno College Address Town District Phone 01 Phone 02 email Code 1 6001 Govt. First Grade College for Boys Kolar - 563 101 Kolar Kolar 9448703610 08152-222014 2 6002 Govt. First Grade College for Women Kolar - 563 101 Kolar Kolar 9448310292 9448551944 3 6003 Govt. First Grade College Bangarpet - 563 114 Bangarpet Kolar 9739601069 4 6004 Govt. First Grade College Bangaru Tirupathi Bangaru Tirupathi Kolar 8277490804 08153-277088 5 6005 Govt. First Grade College Behind BEO Office, Robertsonpet, 3rd Cross, KGF - 563 122 K.G.F Kolar 7204783372 6 6006 Govt. First Grade College Malur - 563 130 Malur Kolar 9886152726 9448562961 7 6007 Govt. First Grade College Mulabagalu - 563 131 Mulbagal Kolar 9886668896 8 6008 Govt. First Grade College Mulabagalu - 563 131 Mulbagal Kolar 9886668896 [email protected] 9 6009 Govt. First Grade College Srinivasapura - 563 135 Srinivasapura Kolar 9663701201 08157-246804 10 6010 Govt. First Grade College Vemgal - 563 101 Vemagal Kolar 9886632427 08152 246499 Smt. Danamma Channabasavaiah College of Arts, Commerce, 11 6101 Opp. to SBI Bank, Kolar Main Road, Bangarpet Bangarpet Kolar 9141814905 9060777990 [email protected] Science & Management Studies K.G.F Main road, near food godown, S.G. Kote post, Bangarpet - 12 6102 Alpha Degree College Bangarpet Kolar 9900023325 563 162 13 6103 K.G.F Frist Grade College Oorgam, K.G.F. - 563 120 K.G.F Kolar 9449730978 9449730798 14 6104 Sri Baghawan Mahaveer Jain Degree College Geetha Road, Robertsonpet, KGF - 563 122 K.G.F Kolar -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, MAQUAT 10, 08/08/2008

UNiTED ST.c~S ENVIRONMENTA.L'PROTECTI9NAGC1V [o3J-Cf -63' ~/g-'fcH;oe Ms. Elizabeth Tannehill Mason Chemical Company .r~~---~ .. 721 W. Algonquin Road ",'". 'I' ~1 , ,r: Arlington Heights, IL 60005 AUG 8 200a Subject: Maquat 10 EPA Registration No.: 10324-63 Amendment Date: March 19,2008 EP A Receipt Date: March 28, 2008 Dear Ms. Tannehill, The following amendment, submitted in connection With registration under section 3(c)(7)(A) of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and.Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), as amended, is 'acceptable subject to the conditions listed below: • Addition of public health organisms • Addition of directions for use and marketing claims • ,Acceptable Data Correct your data matrix to indicate the correct MRIDs: Porcine Rotavinis: 45171410 and Porcine Respiratory and Reproductive Syndrome: 45171409. Community Associated Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Submitted study,.MRID473868-01 Acceptable, 625 ppm active in 5% . soil for 10 minutes Avian Influenza A (H5Nl) virus Submitted study, MRID 473868-02 Acceptable, 625 ppm active in 5% soil for 10 minutes Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 Submitted study, MRID 47386g~03 Acceptable, 625 ppm active in 5% soil for 2 minutes cONcuRReNces.' " . .. SYMBOL ••• J§l~.e ...................... _.~ ................ .. 0.............. ·o ••• _~ ......~....... .. .~O... ...• ....... .. .... 00"' ......... 0... ..0 .• 00." ...... SURNAME" -.;. ~ . DA1"E .; ••• ~J;j6~ .......... ~ ........... ~ .............. •••••••••••••••• ~~ •.•••• ~.......... ••••••••••••••••• • .............. _ ••••• ~ •••••• o ••••• ...... OFfiCIAL fiLE COpy EPA Form 1320-1A (1190) P,illud 011 Re~/ed Pa~ UNITED ST[~S ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECT'ION AGC~CY Conditions Revise the label as follows: 1) Delete the following organism from the "Food Contact SanitiZing Performance" section on pages three and twelve: Clostridium perfringens-vegetative. The Agency is not longer accepting claims of effectiveness against the vegetative form of this organism. -

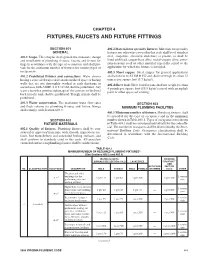

Chapter 4 Fixtures, Faucets and Fixture Fittings

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen CHAPTER 4 FIXTURES, FAUCETS AND FIXTURE FITTINGS SECTION 401 402.2 Materials for specialty fixtures. Materials for specialty GENERAL fixtures not otherwise covered in this code shall be of stainless 401.1 Scope. This chapter shall govern the materials, design steel, soapstone, chemical stoneware or plastic, or shall be and installation of plumbing fixtures, faucets and fixture fit- lined with lead, copper-base alloy, nickel-copper alloy, corro- tings in accordance with the type of occupancy, and shall pro- sion-resistant steel or other material especially suited to the vide for the minimum number of fixtures for various types of application for which the fixture is intended. occupancies. 402.3 Sheet copper. Sheet copper for general applications 401.2 Prohibited fixtures and connections. Water closets shall conform to ASTM B 152 and shall not weigh less than 12 having a concealed trap seal or an unventilated space or having ounces per square foot (3.7 kg/m2). walls that are not thoroughly washed at each discharge in 402.4 Sheet lead. Sheet lead for pans shall not weigh less than accordance with ASME A112.19.2M shall be prohibited. Any 4 pounds per square foot (19.5 kg/m2) coated with an asphalt water closet that permits siphonage of the contents of the bowl paint or other approved coating. back into the tank shall be prohibited. Trough urinals shall be prohibited. 401.3 Water conservation. The maximum water flow rates SECTION 403 and flush volume for plumbing fixtures and fixture fittings MINIMUM PLUMBING FACILITIES shall comply with Section 604.4. -

2 the Robo-Toilet Revolution the Actress and the Gorilla

George, Rose, 2014, The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters (pp. 39-64). Henry Holt and Co.. Kindle Edition. 2 THE ROBO-TOILET REVOLUTION THE ACTRESS AND THE GORILLA The flush toilet is a curious object. It is the default method of excreta disposal in most of the industrialized, technologically advanced world. It was invented either five hundred or two thousand years ago, depending on opinion. Yet in its essential workings, this everyday banal object hasn’t changed much since Sir John Harington, godson of Queen Elizabeth I, thought his godmother might like something that flushed away her excreta, and devised the Ajax, a play on the Elizabethan word jakes, meaning privy. The greatest improvements to date were made in England in the later years of the eighteenth century and the early years of the next by the trio of Alexander Cumming (who invented a valve mechanism), Joseph Bramah (a Yorkshireman who improved on Cumming’s valve and made the best lavatories to be had for the next century), and Thomas Crapper (another Yorkshireman who did not invent the toilet but improved its parts). In engineering terms, the best invention was the siphonic flush, which pulls the water out of the bowl and into the pipe. For the user, the S-bend was the godsend, because the water that rested in the bend created a seal that prevented odor from emerging from the pipe. At the height of Victorian invention, when toilets were their most ornate and decorated with the prettiest pottery, patents for siphonic flushes, for example, were being requested at the rate of two dozen or so a year. -

Innovative Carbon Capture Through Enhanced Fecal Sludge Management

China, People's Republic of: Innovative Carbon Capture through enhanced Fecal Sludge Management Project Name Innovative Carbon Capture through enhanced Fecal Sludge Management Project Number 52290-001 Country China, People's Republic of Project Status Proposed Project Type / Modality of Technical Assistance Assistance Source of Funding / Amount Strategic Agendas Environmentally sustainable growth Inclusive economic growth Drivers of Change Governance and capacity development Knowledge solutions Partnerships Private sector development Sector / Subsector Water and other urban infrastructure and services - Urban sanitation Gender Equity and Effective gender mainstreaming Mainstreaming Description The technical assistance (TA) will support the development of carbon sequestration and safe carbon sink plans resulting from enhanced tree irrigation through improved fecal sludge management (FSM) practices. A market assessment funded by the Sanitation Financing Partnership Trust Fund (SPF) under the Water Financing Partnership Facility (WFPF) has recommended enhanced fecal sludge management practices that can result in reusing treated sludge for the safe irrigation of trees in the Beijing Capital Region (BCR) and other water-stressed cities in the People's Republic of China (PRC). As a result of improved irrigation practices, improved tree growth will function as carbon sink, improving carbon capture. Project Rationale and Linkage Both water shortages and increased energy consumption are serious climate mitigation issues in PRC. to Country/Regional Strategy The Government is responding by investing in carbon dioxide (CO2) mitigation measures and although carbon capture technologies hold promise, trees remain the best carbon sink. Trees need water and water starved areas in Northern China, including BCR, face energy-intensive and expensive alternatives to meet increasing water demand.