Technological Discontinuities, Radical Innovation and Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chequered Flag

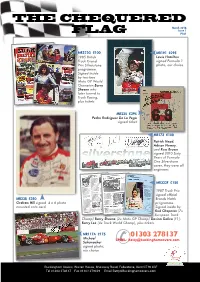

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

Purpose Driven Initiative / 2

A report on the Contribution of Motorsport to Health, Safety & the Environment Commissioned by the Created by #PurposeDriven A PURPOSE DRIVEN INITIATIVE / 2 FOREWORD 03 SUPERIOR ELECTRIC 43 INTRODUCTION 04 15. Leading The Charge 44 16. Beyond The Battery 46 METHODOLOGY 07 17. Going The Extra Mile 48 BETTER HEALTHCARE 09 18. The Lightning Laboratory 50 01. Racing Against The Pandemic 10 HYPER EFFICIENCY 52 02. Collaboration In A Crisis 12 19. Back To The Future 53 03. Keeping Fingers On The Pulse 14 20. Electrifying Progress 55 04. Transplanting Technology 16 21. Shifting The Paradigm 57 05. The World’s Safest Crib 18 22. Going Against The Flow 59 06. Operation Pit Stop 20 23. Transforming Tyres 61 GREENER LIVING 22 ALONG THE ROAD 63 07. Putting Waste On Ice 23 24. Additive Acceleration 64 08. The Great Data Race 25 25. Fueling Forward Thinking 66 09. Reinventing Two Wheels 27 26. The Ultimate Showcase 68 10. Flying In The Drivers Seat 29 11. Aerodynamic Architecture 31 CONCLUSION 70 SAFER MOTORISTS 33 INDEX / SOURCES 77 12. Setting The Standard 34 13. A Model For Safety 37 14. A Foundation For Society 40 A PURPOSE DRIVEN INITIATIVE FORWARD / 3 Foreword by President Jean Todt Ladies, Gentlemen, Motorsport has always participated in the progress of society, particularly in terms of technology and innovation to improve health and safety as well as to protect our environment. Advances on the racetrack find their way to the road, helping to preserve lives and the planet. This has probably never been as clear as in the response of the community to the global pandemic this year. -

Esplode L'ira Mclaren Tre Le Partite Che Le Restano (A Napoli, Con Le Riunite in Casa E a TERZA FILA Milano Con La Philips)

G.P. DEL BRASILE Basket Nell'anticipo La lunghetta Infuria la polemica. Ron Dennis attacca del nuovo tracciato, ————— la Ferrari: «È la rovina della RI Benetton incontenibile dove si corre per la prima volta. Grazie alla Fiat ha troppi soldi e si comporta in modo scorretto Per Montecatini si apre è di 4.810 metri Alain Prost? Meglio per lui lasciare i motori e dedicarsi alla famiglia» il baratro delTA2 •• ROMA Montecatini è con un piede nell'A2, Treviso con un Senna, 43* pole posltion piede nel play-off. È quanto viene fuori dall'anticipo del basket di vertice che ha visto len la Benetton passare per 92-83 sul campo PRIMARIA del toscani A due punti di distacco dalla Roberts in classifica, ma con due vittorie di distacco per una differenza punti sfavorevole 1) Senna (McLaren) rir'277 2|Berger (McLaren) V17"888 negli scontri diretti con I fiorentini (-5), la Panapesca resta in Al SECONDA FILA solo per la matematica. Per sperare dovrebbe ora vincere tutte e 3) Boutsen (Williams) I'18"150 4) Patre„ rwilllams) I'18'288 Esplode l'ira McLaren tre le partite che le restano (a Napoli, con le Riunite in casa e a TERZA FILA Milano con la Philips). impresa che, vista l'occasione persa con la Benetton, appare impossibile. Nella gara di ieri ai toscani è ve 5) Mansell (Ferrari) V18"509 6) pros,(Ferrari) rWm «La politica della Ferrari può destabilizzare la For da novanta da lanciare sull'av tersi queste cose perche ha la tende raggiungere: qui a San nuto meno proprio l'approccio psicologico all'impegno. -

Download the Press Release

PRESS RELEASE // FEBRUARY 2018 MCLAREN – RICHARD MILLE RETURN ON THE 55 YEARS OF EXISTENCE OF A F1 CHAMPION Luxury Swiss watch maker Richard Mille return on the history of one of the greatest Formula One racing team : McLaren. Today second most successful team in the championship history, the british company founded by New Zealander Bruce McLaren has set mutiple records during its life. Return on 55 years of success. A HIGH SPEED RISE Although he initially intended to a sports career, his heart goes to an other famous sport in his home country : rugby. After an injury he gets interested with great success towards automotive sports. He mades his competitives debuts in 1958 and quickly establish himself as an amazing motorcycle driver. One year later, aged 22 years and 80 days, Bruce McLaren becomes the youngest ever racer in the history of Formula One to win a race : the United States Grand Prix. McLaren M2B THE EARLY STAGES OF MCLAREN In 1963, while still involved in the Cooper racing team, the champion founds the Bruce McLaren Motor Racing. It’s only in 1966, that he creates his own racing team and design his first F1 with the young engineer Robin Herb. Named M2 B, this vehicle will be presented this year at Rétromobile. McLaren competitive debuts aren’t successful nonetheless the ranking of the team at the end of the season is saved thanks to motorisations upgrades and a victory with a Ford GT40 at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. After a great 1967 season, McLaren compete with a brand new car seen as the finest-looking Bruce McLaren M8D single-seater : the M7A. -

Karl E. Ludvigsen Papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26

Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Miles Collier Collections Page 1 of 203 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Title: Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Creator: Ludvigsen, Karl E. Call Number: Archival Collection 26 Quantity: 931 cubic feet (514 flat archival boxes, 98 clamshell boxes, 29 filing cabinets, 18 record center cartons, 15 glass plate boxes, 8 oversize boxes). Abstract: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers 1905-2011 contain his extensive research files, photographs, and prints on a wide variety of automotive topics. The papers reflect the complexity and breadth of Ludvigsen’s work as an author, researcher, and consultant. Approximately 70,000 of his photographic negatives have been digitized and are available on the Revs Digital Library. Thousands of undigitized prints in several series are also available but the copyright of the prints is unclear for many of the images. Ludvigsen’s research files are divided into two series: Subjects and Marques, each focusing on technical aspects, and were clipped or copied from newspapers, trade publications, and manufacturer’s literature, but there are occasional blueprints and photographs. Some of the files include Ludvigsen’s consulting research and the records of his Ludvigsen Library. Scope and Content Note: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers are organized into eight series. The series largely reflects Ludvigsen’s original filing structure for paper and photographic materials. Series 1. Subject Files [11 filing cabinets and 18 record center cartons] The Subject Files contain documents compiled by Ludvigsen on a wide variety of automotive topics, and are in general alphabetical order. -

GI-FUMETTI-PAGINE <38 TOPPI>

TUTTO SUL MONDIALE Le scuderie 2001 I piloti I circuiti Il calendario dei Gran Premi Gli albi d’oro I primati Foto di C. Galimberti - Olympia (1 - continua) IL GIORNALINO 38 n. 15/2001 va porta con sé tutta l’esperienza accumula- ta in questi anni». – Cerca di essere sincero: è vero che tutti i La scheda di Jarno piloti italiani stravedono per la Ferrari? Jarno Trulli ha quasi 27 anni, essen- «Ora che stanno dominando la scena, non do nato a Pescara il 13 luglio 1974, e L’abruzzese Jarno Trulli, insieme con Giancarlo Fisichella, rappresenta il tricolore tra i piloti più veloci sarebbe male potersi sedere al volante delle risiede a Francavilla, in provincia di macchine di Maranello. Fino a qualche anno Chieti. del mondo. Il suo obiettivo è ben figurare con la Jordan. E magari vincere un Gran Premio... fa non era la stessa cosa, la Ferrari ti dava sol- Alto 1,73 per 60 kg di peso forma, tanto una maggiore popolarità. Comunque il deve il suo insolito nome all’ammirazio- on Giancarlo Fisichella rappresenta la primo traguardo di un pilota resta sempre ne di suo padre Enzo per il pilota finlan- scuola italiana in Formula 1. E, come quello di trovare una scuderia che ti offra la dese Saarinen, vincitore del Motomon- Cnel caso del pilota romano, pure a lui il possibilità di vincere». diale (classe 250) nel ’72 e scomparso ruolo di eterna promessa incomincia ad anda- – Sei favorevole alla liberalizzazione del- tragicamente nel maggio del ’73. re stretto. Alla seconda stagione con la Jor- l’elettronica in Formula 1? La sua marcia di avvicinamento al dan, Jarno Trulli rilancia la sfida ai colleghi «Sì. -

Fressingfield Oily Rag Club FORC

Fressingfield Oily Rag Club Newsletter October/November 2017 FORC: “A loose affiliation of motor sport enthusiasts”. Design Norman Reynolds October/November 2017 The View From The Editorial Desk Wednesday November 22nd: Only a week to go to our penultimate Stradbroke meeting of 2017: Steve Nichols in conversation with our very good friend Motor Sport Magazine features editor Simon Arron. If you aren't among the 100 or so who have already booked to come and hear Steve the following should convince you to hurry up and do it now! Following an early career with Hercules Aerospace Steve joined McLaren Formula One in 1980 becoming head car designer when John Barnard left for Ferrari in 1987. His first car, the McLaren MP4/3, with TAG-Porsche V6 Turbo, gave Alain Prost three victories in 1987. Prost's team-mate, Stefan Johansson also scored five podiums. Steve's second car the iconic MP4/4, this time powered by a turbocharged Honda V6, was driven to 15 victories from 16 races in 1988, by Prost and Ayrton Senna. At the end of 1989 Steve was tempted away from McLaren to Ferrari where he rejoined Alain Prost staying until December 1991- so our first Ferrari guest speaker! Steve was subsequently enlisted to help Sauber move from sports-car racing to Formula One before moving to Jordan as Chief Designer. Steve rejoined McLaren in 1995 assisting the team to move from the back of the grid to winning world championships in 1998 and 1999....if that wasn't all today Steve races in Historic FF2000 as well as making regular trips to play in historic racing back in USA! Another memorable evening in store I suspect.. -

2014 Acura Mdx

2014 acura mdx Continue Japanese crossover Acura MDXOverviewManufacturAcura (Honda)Production2000-present (Acura)2003-2006 (Honda)Model years2001-presentBody and chassisClass-sized luxury crossoverBodi style5-door SUV or Honda MDX, as is known in Japan and Australia (only the first generation was imported), is a mid-size three-row luxury crossover, 3 4 5 produced by Japanese automaker Honda under its luxury acura plate since 2000. The alphabetical nickname means Multidimensional Luxury. According to Honda, the MDX is the best-selling three-way luxury crossover of all time, with total sales in the U.S. expected to exceed 700,000 units by the end of 2014. It came in second place in the luxury crossover sales after the Lexus RX, which offers only two rows of seats. The MDX was the first crossover that has a third row of seats, and shares the platform with the Honda Pilot. The pilot seats eight, while the MDX seats seven, with two seats in the third row. The MDX was introduced on October 5, 2000 as a 2001 model, replacing the slow-selling American body-on-frame SLX based on the Isuzu Trooper. In Japan, it filled the gap when Honda Horizon (also based on Trooper) was discontinued in 1999. In 2003, Honda MDX went on sale in Japan and Australia. The MDX was the most expensive crossover in the Acura lineup, with the exception of the 2009-13 model years, when Acura added a crossover to the slot over the MDX, called THED. Первое поколение (YD1; 2000) Первое поколение (YD1)2001-2003 Acura MDXOverviewProduction2000-2006 (Acura)2003-2006 (Honda)Модель лет2001-2006AssemblyAlliston, Онтарио, Онтарио, Канада (HCM)КонструкторФранк Палух (инженерия: 1998), Каталин Матей (стиль: 1998)Кузов и шассиЛаутФронт двигатель, полный приводСвязанныйHonda PilotPowertrainEngine3.5 L V6 240 л.с. -

Eleven Sports 3

ELEVEN SPORTS 3 - VERSÃO 1 SEMANA 22 Time 25/05/2020 - Seg 26/05/2020 - Ter 27/05/2020 - Qua 28/05/2020 - Qui 29/05/2020 - Sex 30/05/2020 - Sáb 31/05/2020 - Dom Time 05:00 05:00 05:15 05:15 05:30 05:30 05:45 05:45 06:00 06:00 06:15 06:15 06:30 06:30 06:45 06:45 07:00 07:00 07:15 07:15 07:30 07:30 07:45 07:45 08:00 08:00 08:15 08:15 08:30 08:30 08:45 08:45 09:00 09:00 09:15 09:15 09:30 09:30 09:45 LOOP ELEVENSPORTS 09:45 10:00 ARCHITECTS OF F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 10:00 10:15 GORDON MURRAY JOHN BARNARD JO RAMIREZ MAX MOSLEY GORDON MURRAY GORDON MURRAY 10:15 10:30 ESPECIAL: 10:30 10:45 1000 GP 10:45 11:00 LEGENDS OF F1 LEGENDS OF F1 LEGENDS OF F1 LEGENDS OF F1 LEGENDS OF F1 LEGENDS OF F1 11:00 11:15 GERHARD BERGER MARIO ANDRETTI JOHN WATSON JUAN PABLO MONTOYA NIGEL MANSELL GERHARD BERGER 11:15 11:30 2019 11:30 11:45 FILLERS 11:45 12:00 F1 ELEVEN F1 ELEVEN F1 ELEVEN F1 ELEVEN F1 ELEVEN TALES FROM THE VAULT TALES FROM THE VAULT 12:00 12:15 12:15 12:30 TEMPORADA 1: EP17 TEMPORADA 1: EP18 TEMPORADA 1: EP15 TEMPORADA 1: EP16 TEMPORADA 1: EP17 12:30 12:45 LOTUS THE STORY OF 1984 12:45 13:00 ARCHITECTS OF F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 13:00 13:15 REPETIÇÃO FACEBOOK REPETIÇÃO FACEBOOK REPETIÇÃO FACEBOOK REPETIÇÃO FACEBOOK REPETIÇÃO FACEBOOK MAX MOSLEY JOHN BARNARD 13:15 13:30 ARCHITECTS OF F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 ARCHITECTS OF F1 13:30 13:45 GORDON MURRAY JOHN BARNARD JO RAMIREZ MAX MOSLEY JOHN BARNARD 13:45 14:00 GP CONFIDENTIAL F1 ESPORTS 14:00 14:15 PREVIEW -

Download a Report on the Contribution of Motor Sport To

A report on the Contribution of Motorsport to Health, Safety & the Environment Commissioned by the Created by #PurposeDriven A PURPOSE DRIVEN INITIATIVE / 2 FOREWORD 03 SUPERIOR ELECTRIC 43 INTRODUCTION 04 15. Leading The Charge 44 16. Beyond The Battery 46 METHODOLOGY 07 17. Going The Extra Mile 48 BETTER HEALTHCARE 09 18. The Lightning Laboratory 50 01. Racing Against The Pandemic 10 HYPER EFFICIENCY 52 02. Collaboration In A Crisis 12 19. Back To The Future 53 03. Keeping Fingers On The Pulse 14 20. Electrifying Progress 55 04. Transplanting Technology 16 21. Shifting The Paradigm 57 05. The World’s Safest Crib 18 22. Going Against The Flow 59 06. Operation Pit Stop 20 23. Transforming Tyres 61 GREENER LIVING 22 ALONG THE ROAD 63 07. Putting Waste On Ice 23 24. Additive Acceleration 64 08. The Great Data Race 25 25. Fueling Forward Thinking 66 09. Reinventing Two Wheels 27 26. The Ultimate Showcase 68 10. Flying In The Drivers Seat 29 11. Aerodynamic Architecture 31 CONCLUSION 70 SAFER MOTORISTS 33 INDEX / SOURCES 77 12. Setting The Standard 34 13. A Model For Safety 37 14. A Foundation For Society 40 A PURPOSE DRIVEN INITIATIVE FORWARD / 3 Foreword by President Jean Todt Ladies, Gentlemen, Motorsport has always participated in the progress of society, particularly in terms of technology and innovation to improve health and safety as well as to protect our environment. Advances on the racetrack find their way to the road, helping to preserve lives and the planet. This has probably never been as clear as in the response of the community to the global pandemic this year. -

14 Queens Gate Place Mews, London, Sw7 5Bq Phone +44 (0)20 7584 3503 Fax +44 (0)20 7584 7403 E-Mail [email protected] 1982 Mclaren Mp4/1B-6

14 QUEENS GATE PLACE MEWS, LONDON, SW7 5BQ PHONE +44 (0)20 7584 3503 FAX +44 (0)20 7584 7403 E-MAIL [email protected] 1982 MCLAREN MP4/1B-6 1982 McLaren MP4/1B-6 (M10) ex-Niki Lauda Piloted by Niki Lauda for the 1983 season, MP4/1B-6 won the British GP at Brands Hatch McLaren's pioneering ground eect Formula One design - the rst carbon bre composite chassis Design by John Barnard, a superlative engineer of modern F1, featured in his recent biography The Perfect Car Fully restored by TAG-McLaren for the company collection, including new monocoque Winner of two FIA Historic Formula One Championships, raced by its current private owner 3-litre Cosworth-Ford V8 power, naturally aspirated An opportunity to acquire a Grand Prix winning example of McLaren’s revolutionary MP4/1, the rst carbon bre composite chassis in Formula One. Conceived by John Barnard, a gifted and perfectionist engineer at Project Four (the “P4” in MP4), Barnard wanted a narrow chassis to maximize the ground eect area of the side pods – needing a new material to replace lost strength, he turned to carbon bre, visiting British Aerospace facilities to see its application. With every layer precisely calculated, Barnard said working with carbon bre was “more like tailoring than building a car.” Today every Formula One chassis is carbon – MP4/1 changed the sport forever. Our thoughtful purchaser will not only acquire an outstandingly competitive racer for historic Formula One – they also acquire the ultimate expression of a brilliant idea. With McLaren struggling in the late seventies, the team was merged with Project Four, the latter contributing its strong-willed engineer and his promising new design. -

Ayrton Senna - Mclaren Pdf

FREE AYRTON SENNA - MCLAREN PDF Maurice Hamilton | 288 pages | 01 May 2014 | Bonnier Books Ltd | 9781905825875 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom McLaren Senna Review, Pricing, and Specs Senna began his motorsport career in karting Ayrton Senna - McLaren, moved up to open-wheel racing inand won the British Formula Three Championship. He made his Formula One debut with Toleman - Hart inbefore moving to Lotus - Renault the following year and winning six Grands Prix over the next three seasons. Between them, they won all but one of the 16 Grands Prix that year, and Senna claimed his first World Championship. Prost claimed the championship inand Senna his second and third championships in and Ayrton Senna - McLaren Inthe Williams - Renault combination began to dominate Formula One. Senna nonetheless managed to finish the season as runner-up, winning five races and negotiating a move to Williams in Senna has often been voted as the best and most influential Formula Ayrton Senna - McLaren driver of all time in various motorsport polls. Ayrton Senna - McLaren holds a record six victories at the Monaco Grand Prixand is the fifth-most successful driver of all time in terms of race wins. Senna courted controversy throughout his career, particularly during his turbulent rivalry with Prost. In the Japanese Grands Prix of andeach of which decided the championship of that year, collisions between Senna and Prost determined the eventual winner. It was located on the corner of Avenida Aviador Guilherme with Avenida Gil Santos Dumont, less than meters from Campo de Marte, a large area where they operated the Aeronautics Material park and an airport.