Two Advantages to a Writing System: 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

Linguistic Study About the Origins of the Aegean Scripts

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 15 (2016-2017) Essays 1 Cretan Hieroglyphics The Ornamental and Ritual Version of the Cretan Protolinear Script The Cretan Hieroglyphic script is conventionally classified as one of the five Aegean scripts, along with Linear-A, Linear-B and the two Cypriot Syllabaries, namely the Cypro-Minoan and the Cypriot Greek Syllabary, the latter ones being regarded as such because of their pictographic and phonetic similarities to the former ones. Cretan Hieroglyphics are encountered in the Aegean Sea area during the 2nd millennium BC. Their relationship to Linear-A is still in dispute, while the conveyed language (or languages) is still considered unknown. The authors argue herein that the Cretan Hieroglyphic script is simply a decorative version of Linear-A (or, more precisely, of the lost Cretan Protolinear script that is the ancestor of all the Aegean scripts) which was used mainly by the seal-makers or for ritual usage. The conveyed language must be a conservative form of Sumerian, as Cretan Hieroglyphic is strictly associated with the original and mainstream Minoan culture and religion – in contrast to Linear-A which was used for several other languages – while the phonetic values of signs have the same Sumerian origin as in Cretan Protolinear. Introduction The three syllabaries that were used in the Aegean area during the 2nd millennium BC were the Cretan Hieroglyphics, Linear-A and Linear-B. The latter conveys Mycenaean Greek, which is the oldest known written form of Greek, encountered after the 15th century BC. Linear-A is still regarded as a direct descendant of the Cretan Hieroglyphics, conveying the unknown language or languages of the Minoans (Davis 2010). -

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Emojis are often compared to Egyptian hieroglyphs because both use pictures to express meaning. However, Egyptian hieroglyphs were a writing system like the alphabet you are reading now and could be used to write anything. Instead of using letters for sounds, the ancient Egyptians used signs (pictures). Emojis are used differently. They add extra meaning to writing, a bit like how tone of voice and gestures add extra meaning when we’re speaking. You could write this paragraph using the emoji-alphabet at the top of the answer sheet, but that’s not how emojis are normally used. Aside from using signs instead of letters, there are lots of differences between the Scots and English writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one. For example, Egyptian hieroglyphs could be written either right to left or left to right and were often written in columns from top to bottom. Hieroglyphic writing didn’t use vowels. The name for this sort of writing system is an abjad. You can write out English and Scots with an abjad rather than an alphabet and still understand it without too much difficulty. For example: Ths sntnc sn’t vry hrd t rd. The biggest difference between alphabetic writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one is that in hieroglyphic writing a sign could be used in three ways. It could be used as a word (ideogram); as a sound (phonogram); or as an idea-sign (determinative) to make things easier to understand. For example, could be used as an ideogram for the word ‘bee’; as a phonogram for the first sound in ‘belief’; or as a determinative added to the end of the word ‘hive’ to distinguish it from ‘have’ and ‘heave’, which would all be written the same: hv. -

Pictograms: Purely Pictorial Symbols

toponymy course 10. Writing systems Ferjan Ormeling This chapter shows the semantic, phonetic and graphic aspects of language. It traces the development of the graphic aspects from Sumeria 3500BC, from logographic or ideographic via syllabic into alphabetic scripts resulting in a number of script families. It gives examples of the various scripts in maps (see underlined script names) and finally deals with combination of scripts on maps. 03/07/2011 1 Meaning, sound and looks What is the name? - Is it what it means? - Is it what it sounds? - Is it what it looks? 03/07/2011 2 Meaning: the semantic aspect As long as a name is what it means, both its sound and its looks (spelling) are only relevant as far as they support the meaning. The name ‘Nederland’ is wat it means to our neighbours: ‘Low country’. So they translate it for instance into ‘Pays- Bas’ (French) or Netherlands (English) or Niederlande (German), even though that does neither sound nor look like ‘Nederland’. To Romans and Italians, however, the names Qart Hadasht and Neapolis had never been what they meant (‘new towns’). So they became what they sounded: Carthago (to the Roman ear) and Napoli. 03/07/2011 3 Sound: the phonetic aspect As soon as a name is what it sounds, its meaning has become irrelevant. Its looks (spelling) then may or may not be adapted to its sound. The dominance of the phonetic aspect to a name (the ‘oral tradition’) allows the name to degenerate graphically. Eventually, the name may be adapted semantically to its perceived sound, through a process called ‘popular etymology’. -

The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized

American Journal of Applied Psychology 2017; 6(5): 88-92 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajap doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 ISSN: 2328-5664 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5672 (Online) The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized Marcienne Martin ORACLE Laboratory, Observatory of Arts, Civilizations and Literatures, in Their Environment, University of Reunion Island, France Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Marcienne Martin. The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized. American Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 6, No. 5, 2017, pp. 88-92. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 Received: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 25, 2017; Published: October 18, 2017 Abstract: The digital paradigm to which these new technologies (NTIC) belong is at the origin of particular linguistic practices. Internet is an innovator in this field. Indeed, its users want their written communications to be as fast as during oral exchanges; they will choose their knowledge to write on a saving in expressive type. Also wishing to transmit feelings and emotions, they will call upon an iconography, which uses the diacritics as material serving creation of logograms. This redundancy of a diverted punctuation of its original use, but being used “to punctuate” the speech by figurines translating the emotional state of the speaker, is a characteristic of this numerical space. Through the analysis of the corpus taken on the Internet and put in comparison with the hieroglyphic system introduced by Champollion Le Jeune [5] and the graphic evolution of some ideograms, it will be shown that it is always about the same used model, in which a key always initiates a semantic field, and that this process orders a reorganization of the objects of the world through a new scriptural writing. -

Quick Reference Guide to ADA Signage

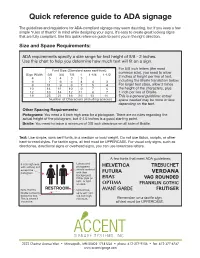

Quick reference guide to ADA signage The guidelines and regulations for ADA-compliant signage may seem daunting, but if you keep a few simple “rules of thumb” in mind while designing your signs, it’s easy to create great looking signs that are fully compliant. Use this quick reference guide to point you in the right direction. Size and Space Requirements: ADA requirements specify a size range for text height of 5/8 - 2 inches. Use this chart to help you determine how much text will fit on a sign. For 5/8 inch letters (the most common size), you need to allow 2 inches of height per line of text, including the Braille translation below. For larger text sizes, allow 2 times the height of the characters, plus 1 inch per line of Braille. This is a general guideline; actual space needed may be more or less depending on the text. Other Spacing Requirements: Pictograms: You need a 6 inch high area for a pictogram. There are no rules regarding the actual height of the pictogram, but 4-4.5 inches is a good starting point. Braille: You need to leave a minimum of 3/8 inch clearance on all side of Braille. Text: Use simple, sans serif fonts, in a medium or bold weight. Do not use italics, scripts, or other hard-to-read styles. For tactile signs, all text must be UPPERCASE. For visual only signs, such as directories, directional signs or overhead signs, you can use lowercase letters. A few fonts that meet ADA guidelines: 6 inch high area Letters and with nothing in it pictograms except the should contrast pictogram. -

On the Origin of Alphabetic Writing

Aren M. Wilson-Wright Radboud University, Nijmegen November 2019 On the Origin of Alphabetic Writing Over the past few years, several scholars have advanced new theories regarding the origin of the alphabetic writing. Douglas Petrovich (2016) and Paul LeBlanc (2017), for example, both argue that the ancient Israelites invented the alphabet during their sojourn in Egypt.1 And in a 2019 article for Bible and Interpretation, Robert Holmstedt suggests that the inhabitants of Byblos developed the alphabet from the earlier Byblos Script, an undeciphered writing system found at the Phoenician city of Byblos. As part of this article, he articulates several important questions about the invention of the alphabetic writing that should guide all future inquiries into the topic: Who invented the alphabet? Where did they come from? Were they familiar with any of the other writing systems used in the ancient Near East? In this article, I will review the inscriptional and historical data that can help us answer these questions, evaluate Holmstedt’s arguments, and present my own theory of alphabetic origins. I. Review of the Evidence The earliest alphabetic inscriptions furnish the primary evidence regarding the invention of the alphabet. These inscriptions come from the Egyptian sites of Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Ḥôl (see map). In 1905, Sir Flinders Petrie (1906: 129–30) discovered ten early alphabetic inscriptions while excavating the Egyptian temple and turquoise mining facility at Serabit el-Khadem. Subsequent excavations at Serabit el-Khadem—from 1920s to the 2000s—have uncovered an additional 37 early alphabetic inscriptions (Lindblom 1931; Butin 1932; Starr and Butin 1936; Gerster 1961: pl. -

Handwriting Toward a Minuscule Alphabet, It Is Written Upright and Is Considered a Majuscule Form

There is much to say about the history of writing. To encapsulate the highlights in an essay by this short essay, it is important to note that the dialectic between formal and informal Jerri-Jo Idarius styles of writing led to periods of degeneration and periods of reform and also to the differentiation between what we refer to as caps and small letters, known technically as majuscules and minuscules. The Roman formal majuscule scripts follow: Although the ascenders and descenders of the half-uncial represent the movement Handwriting toward a minuscule alphabet, it is written upright and is considered a majuscule form. is a craft in which everyone participates, After the fall of Rome, various regional styles developed in Europe but in the 8th yet few people know much about its tradition century King Charlemagne instituted one script throughout the monasteries of Europe or evolution. From the view of a calligrapher* to help unite his empire. This style, known as Carolingian, related to the Roman who has studied and mastered tradi- half uncial and Roman cursive, is the first truly minuscule alphabet. Its beauti- tional forms of handwriting, this lack of ful letters can be written straight or at an angle. A simply drawn form of caps called education is a sign of cultural loss. Most versals appeared in manuscripts of this era. elementary school teachers feel inadequate to teach penmanship, and cannot explain the relationship between the cursive Roman Square Caps (Capitalis Quadrata) handwriting they have to teach and the printed letters they see in books. Since Rustic handwriting is so intimately connected to Uncial self-image, and since most people are (used for Bibles and sacred texts) unhappy with the results of their learning, versals it is common to hear, “I hate my writing!” Carolingian minuscule & or “I never learned to write.” They don’t Medieval scripts are popularly described as blackletter, due to the predomi- know what to do about it. -

History of Writing

History of Writing On present archaeological evidence, full writing appeared in Mesopotamia and Egypt around the same time, in the century or so before 3000 BC. It is probable that it started slightly earlier in Mesopotamia, given the date of the earliest proto-writing on clay tablets from Uruk, circa 3300 BC, and the much longer history of urban development in Mesopotamia compared to the Nile Valley of Egypt. However we cannot be sure about the date of the earliest known Egyptian historical inscription, a monumental slate palette of King Narmer, on which his name is written in two hieroglyphs showing a fish and a chisel. Narmer’s date is insecure, but probably falls in the period 3150 to 3050 BC. In China, full writing first appears on the so-called ‘oracle bones’ of the Shang civilization, found about a century ago at Anyang in north China, dated to 1200 BC. Many of their signs bear an undoubted resemblance to modern Chinese characters, and it is a fairly straightforward task for scholars to read them. However, there are much older signs on the pottery of the Yangshao culture, dating from 5000 to 4000 BC, which may conceivably be precursors of an older form of full Chinese writing, still to be discovered; many areas of China have yet to be archaeologically excavated. In Europe, the oldest full writing is the Linear A script found in Crete in 1900. Linear A dates from about 1750 BC. Although it is undeciphered, its signs closely resemble the somewhat younger, deciphered Linear B script, which is known to be full writing; Linear B was used to write an archaic form of the Greek language. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

History of the Alphabet

History of the Western European Alphabet We’re going to take a look at the evolution of symbols and systems of writing that have become the the letterforms we use today. This survey includes pictographs, cunieforms, hieroglyphics, and Roman Monumental Capitals. My hope in sharing this information with you is that we gain an appreciation for the history and the design of the alphabet, In the book Alphabet: The History, Evolution, and Design and that we do not take these of the Letters We Use Today, Allan Haley writes: letterforms for granted. “Writing is words made visible. The evolution of letterforms In the broadest sense, it is and a system of writing has everything—pictured, drawn, been propelled by our need to represent things, to represent or arranged—that can be turned ideas, to record and preserve into a spoken account. The information, and to express ourselves. For thousands of fundamental purpose of writing years a variety of imaging, is to convey ideas. Our ancestors, tools, and techniques have however, were designers long been used. Marks were made on cave walls, scraped and before they were writers, and stamped into clay, carved in in their pictures, drawings, and stone, and inked on papyrus. arrangements, design played a prominent role in communication from the very beginning”. Cave Painting from Lascaux, 15,000-10,000 BC One of the earliest forms of visual communication is found in cave paintings. The cave paintings found in Lascaux, France are dated from 10,000 to 8000 BC. These images are referred to as pictographs. Pictographs are a concrete representation of an object in the physical world. -

ICA Course on Toponymy

S10: Writing systems 2. SCRIPTS, THE GRAPHICS OF LANGUAGE <previous - next> The cradle of most of the modern phonographic scripts is the Middle East. The oldest known Sumerian and Home Egyptian pictographic inscriptions considered to be scripts date from the 4th millennium BC. | Self study : Scripts were developed to extend man’s scope and range. Writing Systems | Pictograms: purely pictorial symbols. Contents | Pictograms were used to represent the concepts (ideograms) or words (logograms) they represented. Intro | 1.Meaning, Ultimately, logograms develop into phonograms, in which the sound value (phoneme) of mono- sound & looks (a/b/c) syllabic words is attached to the symbols representing these words. | 2.Scripts | Finally the syllabic script develops into an alphabetic script in which symbols represent single 3.Script phonemes instead of syllables. development | 4.Division Universal sequence from purely pictorial representation (pictograms) to sets of abstracted sound- | 5.Basic unit representing symbols (phonograms). of writing Pictograms convey meaning without intervention of sound values; there may be a symbol meaning ‘town’, | ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ irrespective of what the word for ‘town’, ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ sounds like, and thus 6.Logograms | regardless of any specific language. Such a symbol is named a logogram (pictogram for a specific word). 7.Ideographic The advantage of logograms is their universal applicability – because they are language-independent – but and they have the obvious disadvantage that there must be a separate symbol for every word. logographic scripts | All complete writing systems the world has ever known, do effectively contain both logograms and 8.Syllabic phonograms. As purely pictorial ‘proto-scripts’ develop into ‘scripts’ or writing systems, naturally drawn scripts pictograms are stylised and augmented with drawings for abstract phenomena (hence called ideograms), | 9.Alphabetic and will ultimately contain logograms for all basic words of a specific language.