The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs and Pictograms Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ogham-Runes and El-Mushajjar

c L ite atu e Vo l x a t n t r n o . o R So . u P R e i t ed m he T a s . 1 1 87 " p r f ro y f r r , , r , THE OGHAM - RUNES AND EL - MUSHAJJAR A D STU Y . BY RICH A R D B URTO N F . , e ad J an uar 22 (R y , PART I . The O ham-Run es g . e n u IN tr ating this first portio of my s bj ect, the - I of i Ogham Runes , have made free use the mater als r John collected by Dr . Cha les Graves , Prof. Rhys , and other students, ending it with my own work in the Orkney Islands . i The Ogham character, the fair wr ting of ' Babel - loth ancient Irish literature , is called the , ’ Bethluis Bethlm snion e or , from its initial lett rs, like “ ” Gree co- oe Al hab e t a an d the Ph nician p , the Arabo “ ” Ab ad fl d H ebrew j . It may brie y be describe as f b ormed y straight or curved strokes , of various lengths , disposed either perpendicularly or obliquely to an angle of the substa nce upon which the letters n . were i cised , punched, or rubbed In monuments supposed to be more modern , the letters were traced , b T - N E E - A HE OGHAM RU S AND L M USH JJ A R . n not on the edge , but upon the face of the recipie t f n l o t sur ace ; the latter was origi al y wo d , s aves and tablets ; then stone, rude or worked ; and , lastly, metal , Th . -

Early-Alphabets-3.Pdf

Early Alphabets Alphabetic characteristics 1 Cretan Pictographs 11 Hieroglyphics 16 The Phoenician Alphabet 24 The Greek Alphabet 31 The Latin Alphabet 39 Summary 53 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS 1 / 53 Alphabetic characteristics 3,000 BCE Basic building blocks of written language GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 2 / 53 Early visual language systems were disparate and decentralized 3,000 BCE Protowriting, Cuneiform, Heiroglyphs and far Eastern writing all functioned differently Rebuses, ideographs, logograms, and syllabaries · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 3 / 53 HIEROGLYPHICS REPRESENTING THE REBUS PRINCIPAL · BEE & LEAF · SEA & SUN · BELIEF AND SEASON GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 4 / 53 PETROGLYPHIC PICTOGRAMS AND IDEOGRAPHS · CIRCA 200 BCE · UTAH, UNITED STATES GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 5 / 53 LUWIAN LOGOGRAMS · CIRCA 1400 AND 1200 BCE · TURKEY GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 6 / 53 OLD PERSIAN SYLLABARY · 600 BCE GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 7 / 53 Alphabetic structure marked an enormous societal leap 3,000 BCE Power was reserved for those who could read and write · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 8 / 53 What is an alphabet? Definition An alphabet is a set of visual symbols or characters used to represent the elementary sounds of a spoken language. –PM · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 9 / 53 What is an alphabet? Definition They can be connected and combined to make visual configurations signifying sounds, syllables, and words uttered by the human mouth. -

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing. -

Writing Like an Ancient Scribe the Earliest Alphabet

Writing Like an Ancient Scribe The Earliest Alphabet Topics: Communication Image credit: Coron’s Sources of Fonts (Geocities) Writing, Languages Students play the role of Ugaritic scribes in this activity when they use a stylus to Materials List stamp cone-shaped marks into clay. Polymer clay Roller (to flatten To Do and Notice clay) (optional) 1. Roll out polymer clay into 5 mm (~1/4”) slabs. Triangular game 2. Use the game piece or other triangular stylus to imprint letters into the clay using piece or other the Ugaritic alphabet table on page 2. similar object to use as a stylus The Content Behind the Activity Learning an alphabet means recognizing a squiggle, line or other form as a sound. This process is decoding, whether it involves reading English written in the Roman alphabet or the oldest known alphabet: Ugaritic, a cuneiform alphabet written into clay tablets. This activity can be used The development of written language ranks high among important events in the to teach: history of human technology. Cuneiform writing dates back 5500 years, to the Knowledge and “cradle of civilization”, the Middle East. Several written forms used these cone- understanding of the shaped marks, including the Sumerians in Mesopotamia (current-day Iraq). However, past (National the Ugaritic alphabet is considered the first true alphabet (as opposed to writing based Curriculum for Social Studies: Theme 2, on syllables or words), and the letter order eventually influenced the Greek and Time, Continuity, & Roman alphabets. This writing system was employed in the city of Ugarit, located in Change) western Syria from around 1300 BCE. -

Unified English Braille Webinar Presentation

Unified English Braille: A Place to Start Webinar • UEB Ain't Hard to Do by Mark Brady a NYC Teacher of the Visually Impaired • The lyrics and sound file can be found on the Paths to Literacy website • http://www.pathstoliteracy.org/resources/farewell-song-9-ebae- contractions Unified English Braille A Place to Start April 2016 Donna Mayberry, M.Ed., NCUEB LAUREL REGIONAL PROGRAM, Lynchburg, VA [email protected] Webinar Content: • Overview of UEB • Unified English Braille Reference Sheets • Unified English Braille Student Progress Checklists • Converting Bookshare files into UEB • Teacher Relicensure: Option 8 • NCUEB • Questions Overview of UEB The Rules of Unified English Braille Second Edition 2013 Available as a PDF or BRF http://www.iceb.org/ueb.html Your new best Friend!!! What are teacher’s using to learn UEB? •Hadley School for the Blind •VDBVI Saturday Seminars •Update to UEB Self Directed Course- Available in Word, PDF, BRF, DXB http://www.cnib.ca/en/living/braille/Pages/Transcribers-UEB-Course.aspx •The new textbook that is being used in the VI Consortium is: Ashcroft's Programmed Instruction: Unified English Braille by M. Cay Holbrook 2014 Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille Contractions o'c o'clock (shortform) 4 dd (groupsign between letters) 6 to (wordsign unspaced from following word) 96 into (wordsign unspaced from following word) 0 by (wordsign unspaced from following word) # ble (groupsign following other letters) - com (groupsign at beginning of word) ,n ation (groupsign following other letters) ,y ally (groupsign following other letters) Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille- 2 Punctuation 7 opening and closing parentheses (round brackets) 7' closing square bracket 0' closing single quotation mark (inverted commas) ''' ellipsis -- dash (short dash) ---- double dash (long dash) ,7 opening square bracket Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille- 3 Composition signs (indicators) 1 non-Latin (non-Roman) letter indicator @ accent sign (nonspecific) @ print symbol indicator . -

Exhibition Checklist I. Creating Palmyra's Legacy

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST 1. Caravan en route to Palmyra, anonymous artist after Louis-François Cassas, ca. 1799. Proof-plate etching. 15.5 x 27.3 in. (29.2 x 39.5 cm). The Getty Research Institute, 840011 I. CREATING PALMYRA'S LEGACY Louis-François Cassas Artist and Architect 2. Colonnade Street with Temple of Bel in background, Georges Malbeste and Robert Daudet after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 16.9 x 36.6 in. (43 x 93 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 58. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 1 3. Architectural ornament from Palmyra tomb, Jean-Baptiste Réville and M. A. Benoist after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 18.3 x 11.8 in. (28.5 x 45 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 137. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 4. Louis-François Cassas sketching outside of Homs before his journey to Palmyra (detail), Simon-Charles Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 20. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 5. Louis-François Cassas presenting gifts to Bedouin sheikhs, Simon Charles-Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41 cm). -

Pictograms: Purely Pictorial Symbols

toponymy course 10. Writing systems Ferjan Ormeling This chapter shows the semantic, phonetic and graphic aspects of language. It traces the development of the graphic aspects from Sumeria 3500BC, from logographic or ideographic via syllabic into alphabetic scripts resulting in a number of script families. It gives examples of the various scripts in maps (see underlined script names) and finally deals with combination of scripts on maps. 03/07/2011 1 Meaning, sound and looks What is the name? - Is it what it means? - Is it what it sounds? - Is it what it looks? 03/07/2011 2 Meaning: the semantic aspect As long as a name is what it means, both its sound and its looks (spelling) are only relevant as far as they support the meaning. The name ‘Nederland’ is wat it means to our neighbours: ‘Low country’. So they translate it for instance into ‘Pays- Bas’ (French) or Netherlands (English) or Niederlande (German), even though that does neither sound nor look like ‘Nederland’. To Romans and Italians, however, the names Qart Hadasht and Neapolis had never been what they meant (‘new towns’). So they became what they sounded: Carthago (to the Roman ear) and Napoli. 03/07/2011 3 Sound: the phonetic aspect As soon as a name is what it sounds, its meaning has become irrelevant. Its looks (spelling) then may or may not be adapted to its sound. The dominance of the phonetic aspect to a name (the ‘oral tradition’) allows the name to degenerate graphically. Eventually, the name may be adapted semantically to its perceived sound, through a process called ‘popular etymology’. -

The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized

American Journal of Applied Psychology 2017; 6(5): 88-92 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajap doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 ISSN: 2328-5664 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5672 (Online) The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized Marcienne Martin ORACLE Laboratory, Observatory of Arts, Civilizations and Literatures, in Their Environment, University of Reunion Island, France Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Marcienne Martin. The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized. American Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 6, No. 5, 2017, pp. 88-92. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 Received: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 25, 2017; Published: October 18, 2017 Abstract: The digital paradigm to which these new technologies (NTIC) belong is at the origin of particular linguistic practices. Internet is an innovator in this field. Indeed, its users want their written communications to be as fast as during oral exchanges; they will choose their knowledge to write on a saving in expressive type. Also wishing to transmit feelings and emotions, they will call upon an iconography, which uses the diacritics as material serving creation of logograms. This redundancy of a diverted punctuation of its original use, but being used “to punctuate” the speech by figurines translating the emotional state of the speaker, is a characteristic of this numerical space. Through the analysis of the corpus taken on the Internet and put in comparison with the hieroglyphic system introduced by Champollion Le Jeune [5] and the graphic evolution of some ideograms, it will be shown that it is always about the same used model, in which a key always initiates a semantic field, and that this process orders a reorganization of the objects of the world through a new scriptural writing. -

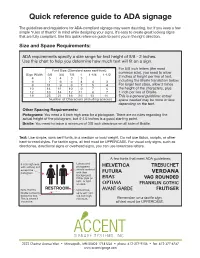

Quick Reference Guide to ADA Signage

Quick reference guide to ADA signage The guidelines and regulations for ADA-compliant signage may seem daunting, but if you keep a few simple “rules of thumb” in mind while designing your signs, it’s easy to create great looking signs that are fully compliant. Use this quick reference guide to point you in the right direction. Size and Space Requirements: ADA requirements specify a size range for text height of 5/8 - 2 inches. Use this chart to help you determine how much text will fit on a sign. For 5/8 inch letters (the most common size), you need to allow 2 inches of height per line of text, including the Braille translation below. For larger text sizes, allow 2 times the height of the characters, plus 1 inch per line of Braille. This is a general guideline; actual space needed may be more or less depending on the text. Other Spacing Requirements: Pictograms: You need a 6 inch high area for a pictogram. There are no rules regarding the actual height of the pictogram, but 4-4.5 inches is a good starting point. Braille: You need to leave a minimum of 3/8 inch clearance on all side of Braille. Text: Use simple, sans serif fonts, in a medium or bold weight. Do not use italics, scripts, or other hard-to-read styles. For tactile signs, all text must be UPPERCASE. For visual only signs, such as directories, directional signs or overhead signs, you can use lowercase letters. A few fonts that meet ADA guidelines: 6 inch high area Letters and with nothing in it pictograms except the should contrast pictogram. -

Origins of the Canaanite Alphabet and West Semitic Consonants' Inventory

DOI 10.30842/alp2306573715317 ORIGINS OF THE CANAANITE ALPHABET AND WEST SEMITIC CONSONANTS’ INVENTORY A. V. Nemirovskaya St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg [email protected] Abstract. It has been not infrequently mentioned by Semitists that a few graphemes of the West Semitic consonantal alphabet had been multifunctional. This is witnessed, in particular, by transcriptions of Biblical names in Septuagint, Demotic transcriptions of Aramaic as well as by the Arabic alphabet, Aramaic by its origin, which twen- ty two graphemes were ultimately developed into twenty eight ones through inventing additional diacritics. The oldest firmly deciphered and convincingly interpreted variety of the West Semitic consonantal script was employed in Ugarit as early as the 13th century BC. Being contemporaneous with the epoch of the invention of the West Semitic consonantal script the most significant evidence is provided with Se- mitic words occasionally transcribed in Egyptian papyri from the New Kingdom. Examples collected (J. Hoch) demonstrate that one and the same Semitic consonant could be recorded variously with different Egyptian consonants used; even more crucial is that various Semitic consonants could be recorded with the same Egyptian one. E. de Rougé was the first one to state that the immediate proto- types of Semitic letters were to be sought among the Hieratic char- acters. W. Helck and K.-Th. Zauzich determined that the West Se- mitic alphabet comprised only those characters which had been used in “Egyptian syllabic writing”. Summarizing philological and histori- cal evidence does allow us to conclude that the Canaanite consonantal alphabet developed as a local adaptation of the Egyptian scribal prac- tice of recording non-Egyptian words. -

The Origin of the Alphabet: an Examination of the Goldwasser Hypothesis

Colless, Brian E. The origin of the alphabet: an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Vol. 12, 2014 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Colless, Brian E. “The origin of the alphabet : an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis” [en línea], Antiguo Oriente : Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente 12 (2014). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/origin-alphabet-goldwasser-hypothesis.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] . 03 Colless - Alphabet_Antiguo Oriente 09/06/2015 10:22 a.m. Página 71 THE ORIGIN OF THE ALPHABET: AN EXAMINATION OF THE GOLDWASSER HYPOTHESIS BRIAN E. COLLESS [email protected] Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Summary: The Origin of the Alphabet Since 2006 the discussion of the origin of the Semitic alphabet has been given an impetus through a hypothesis propagated by Orly Goldwasser: the alphabet was allegedly invented in the 19th century BCE by illiterate Semitic workers in the Egyptian turquoise mines of Sinai; they saw the picturesque Egyptian inscriptions on the site and borrowed a number of the hieroglyphs to write their own language, using a supposedly new method which is now known by the technical term acrophony. The main weakness of the theory is that it ignores the West Semitic acrophonic syllabary, which already existed, and contained most of the letters of the alphabet.