Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Thought of What America": Ezra Pound’S Strange Optimism

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO English Faculty Publications Department of English and Foreign Languages 2010 "The Thought of What America": Ezra Pound’s Strange Optimism John Gery University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/engl_facpubs Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Gery, John “‘The Thought of What America’: Ezra Pound’s Strange Optimism,” Belgrade English Language and Literature Studies, Vol. II (2010): 187-206. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English and Foreign Languages at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UDC 821.111(73).09-1 Pand E. John R O Gery University of New Orleans, USA “THE THOUGHT OF What AMerica”: EZRA POUND’S STRANGE OPTIMISM Abstract Through a reconsideration of Ezra Pound’s early poem “Cantico del Sole” (1918), an apparently satiric look at American culture in the early twentieth century, this essay argues how the poem, in fact, expresses some of the tenets of Pound’s more radical hopes for American culture, both in his unorthodox critiques of the 1930s in ABC of Reading, Jefferson and/or Mussolini, and Guide to Kulchur and, more significantly, in his epic poem, The Cantos. The essay contends that, despite Pound’s controversial economic and political views in his prose (positions which contributed to his arrest for treason in 1945), he is characteristically optimistic about the potential for American culture. -

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Emojis are often compared to Egyptian hieroglyphs because both use pictures to express meaning. However, Egyptian hieroglyphs were a writing system like the alphabet you are reading now and could be used to write anything. Instead of using letters for sounds, the ancient Egyptians used signs (pictures). Emojis are used differently. They add extra meaning to writing, a bit like how tone of voice and gestures add extra meaning when we’re speaking. You could write this paragraph using the emoji-alphabet at the top of the answer sheet, but that’s not how emojis are normally used. Aside from using signs instead of letters, there are lots of differences between the Scots and English writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one. For example, Egyptian hieroglyphs could be written either right to left or left to right and were often written in columns from top to bottom. Hieroglyphic writing didn’t use vowels. The name for this sort of writing system is an abjad. You can write out English and Scots with an abjad rather than an alphabet and still understand it without too much difficulty. For example: Ths sntnc sn’t vry hrd t rd. The biggest difference between alphabetic writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one is that in hieroglyphic writing a sign could be used in three ways. It could be used as a word (ideogram); as a sound (phonogram); or as an idea-sign (determinative) to make things easier to understand. For example, could be used as an ideogram for the word ‘bee’; as a phonogram for the first sound in ‘belief’; or as a determinative added to the end of the word ‘hive’ to distinguish it from ‘have’ and ‘heave’, which would all be written the same: hv. -

Pictograms: Purely Pictorial Symbols

toponymy course 10. Writing systems Ferjan Ormeling This chapter shows the semantic, phonetic and graphic aspects of language. It traces the development of the graphic aspects from Sumeria 3500BC, from logographic or ideographic via syllabic into alphabetic scripts resulting in a number of script families. It gives examples of the various scripts in maps (see underlined script names) and finally deals with combination of scripts on maps. 03/07/2011 1 Meaning, sound and looks What is the name? - Is it what it means? - Is it what it sounds? - Is it what it looks? 03/07/2011 2 Meaning: the semantic aspect As long as a name is what it means, both its sound and its looks (spelling) are only relevant as far as they support the meaning. The name ‘Nederland’ is wat it means to our neighbours: ‘Low country’. So they translate it for instance into ‘Pays- Bas’ (French) or Netherlands (English) or Niederlande (German), even though that does neither sound nor look like ‘Nederland’. To Romans and Italians, however, the names Qart Hadasht and Neapolis had never been what they meant (‘new towns’). So they became what they sounded: Carthago (to the Roman ear) and Napoli. 03/07/2011 3 Sound: the phonetic aspect As soon as a name is what it sounds, its meaning has become irrelevant. Its looks (spelling) then may or may not be adapted to its sound. The dominance of the phonetic aspect to a name (the ‘oral tradition’) allows the name to degenerate graphically. Eventually, the name may be adapted semantically to its perceived sound, through a process called ‘popular etymology’. -

The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized

American Journal of Applied Psychology 2017; 6(5): 88-92 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajap doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 ISSN: 2328-5664 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5672 (Online) The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized Marcienne Martin ORACLE Laboratory, Observatory of Arts, Civilizations and Literatures, in Their Environment, University of Reunion Island, France Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Marcienne Martin. The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized. American Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 6, No. 5, 2017, pp. 88-92. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 Received: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 25, 2017; Published: October 18, 2017 Abstract: The digital paradigm to which these new technologies (NTIC) belong is at the origin of particular linguistic practices. Internet is an innovator in this field. Indeed, its users want their written communications to be as fast as during oral exchanges; they will choose their knowledge to write on a saving in expressive type. Also wishing to transmit feelings and emotions, they will call upon an iconography, which uses the diacritics as material serving creation of logograms. This redundancy of a diverted punctuation of its original use, but being used “to punctuate” the speech by figurines translating the emotional state of the speaker, is a characteristic of this numerical space. Through the analysis of the corpus taken on the Internet and put in comparison with the hieroglyphic system introduced by Champollion Le Jeune [5] and the graphic evolution of some ideograms, it will be shown that it is always about the same used model, in which a key always initiates a semantic field, and that this process orders a reorganization of the objects of the world through a new scriptural writing. -

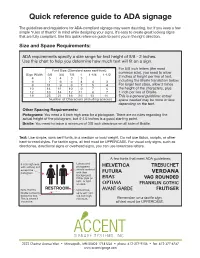

Quick Reference Guide to ADA Signage

Quick reference guide to ADA signage The guidelines and regulations for ADA-compliant signage may seem daunting, but if you keep a few simple “rules of thumb” in mind while designing your signs, it’s easy to create great looking signs that are fully compliant. Use this quick reference guide to point you in the right direction. Size and Space Requirements: ADA requirements specify a size range for text height of 5/8 - 2 inches. Use this chart to help you determine how much text will fit on a sign. For 5/8 inch letters (the most common size), you need to allow 2 inches of height per line of text, including the Braille translation below. For larger text sizes, allow 2 times the height of the characters, plus 1 inch per line of Braille. This is a general guideline; actual space needed may be more or less depending on the text. Other Spacing Requirements: Pictograms: You need a 6 inch high area for a pictogram. There are no rules regarding the actual height of the pictogram, but 4-4.5 inches is a good starting point. Braille: You need to leave a minimum of 3/8 inch clearance on all side of Braille. Text: Use simple, sans serif fonts, in a medium or bold weight. Do not use italics, scripts, or other hard-to-read styles. For tactile signs, all text must be UPPERCASE. For visual only signs, such as directories, directional signs or overhead signs, you can use lowercase letters. A few fonts that meet ADA guidelines: 6 inch high area Letters and with nothing in it pictograms except the should contrast pictogram. -

Determination in the Anatolian Hieroglyphic Script of the Empire and Transitional Period 223

Altorientalische Forschungen 2017; 44(2): 221–234 Annick Payne Determination in the Anatolian Hieroglyphic Script of the Empire and Transitional Period https://doi.org/10.1515/aofo-2017-0019 Abstract: The Anatolian Hieroglyphic script is a mixed writing system which contains both phonetic and semantographic signs. The latter may be used in the function of logogram and/or determinative. A dedicated study of the script’s determinatives has so far not been undertaken but promises insight into structures of mental organization and script development. Because of its pictorial character, individual signs can occasion- ally be shown to act in a dual capacity, as icons and signs of writing. This article forms part one of a diachronic study of the determinative system, and adresses the period 13th–10th century BC. Keywords: Ancient Anatolian writing systems, Anatolian Hieroglyphic script, determinatives Introduction In the Anatolian Hieroglyphic script (AH), determination is one function of the class of semantographic signs. Alternatively, semantographic signs may function as logograms. While logograms represent a word to be read out, determinatives are not intended to be read out, instead, they mark their host word as belonging to a specific semantic category. Thus, determinatives are mute graphemes that act as reading aids, and they are dependent on a host word; with very few exceptions,1 the determinative is placed in front of the host. Different relationships between determinative and host are possible: they may be coordinated or the host may be subordinate to a determinative representing a superordinate category under which several hosts may be subsumed. The script shows numerically equal relationships where one determinative is used for one host, with the aim of reinforcing – less frequently, obstructing – the reading, or of disambiguating it. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

Ezra Pound's Imagist Theory and T .S . Eliot's Objective Correlative

Ezra Pound’s Imagist theory and T .S . Eliot’s objective correlative JESSICA MASTERS Abstract Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot were friends and collaborators. The effect of this on their work shows similar ideas and methodological beliefs regarding theory and formal technique usage, though analyses of both theories in tandem are few and far between. This essay explores the parallels between Pound’s Imagist theory and ideogrammic methods and Eliot’s objective correlative as outlined in his 1921 essay, ‘Hamlet and His Problems’, and their similar intellectual debt to Walter Pater and his ‘cult of the moment’. Eliot’s epic poem, ‘The Waste Land’ (1922) does not at first appear to have any relationship with Pound’s Imagist theory, though Pound edited it extensively. Further investigation, however, finds the same kind of ideogrammic methods in ‘The Waste Land’ as used extensively in Pound’s Imagist poetry, showing that Eliot has intellectual Imagist heritage, which in turn encouraged his development of the objective correlative. The ultimate conclusion from this essay is that Pound and Eliot’s friendship and close proximity encouraged a similarity in their theories that has not been fully explored in the current literature. Introduction Eliot’s Waste Land is I think the justification of the ‘movement,’ of our modern experiment, since 1900 —Ezra Pound, 1971 Ezra Pound (1885–1972) and Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) were not only poetic contemporaries but also friends and collaborators. Pound was the instigator of modernism’s first literary movement, Imagism, which centred on the idea of the one-image poem. A benefit of Pound’s theoretically divisive Imagist movement was that it prepared literary society to welcome the work of later modernist poets such as Eliot, who regularly used Imagist techniques such as concise composition, parataxis and musical rhythms to make his poetry, specifically ‘The Waste Land’ (1922), decidedly ‘modern’. -

ICA Course on Toponymy

S10: Writing systems 2. SCRIPTS, THE GRAPHICS OF LANGUAGE <previous - next> The cradle of most of the modern phonographic scripts is the Middle East. The oldest known Sumerian and Home Egyptian pictographic inscriptions considered to be scripts date from the 4th millennium BC. | Self study : Scripts were developed to extend man’s scope and range. Writing Systems | Pictograms: purely pictorial symbols. Contents | Pictograms were used to represent the concepts (ideograms) or words (logograms) they represented. Intro | 1.Meaning, Ultimately, logograms develop into phonograms, in which the sound value (phoneme) of mono- sound & looks (a/b/c) syllabic words is attached to the symbols representing these words. | 2.Scripts | Finally the syllabic script develops into an alphabetic script in which symbols represent single 3.Script phonemes instead of syllables. development | 4.Division Universal sequence from purely pictorial representation (pictograms) to sets of abstracted sound- | 5.Basic unit representing symbols (phonograms). of writing Pictograms convey meaning without intervention of sound values; there may be a symbol meaning ‘town’, | ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ irrespective of what the word for ‘town’, ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ sounds like, and thus 6.Logograms | regardless of any specific language. Such a symbol is named a logogram (pictogram for a specific word). 7.Ideographic The advantage of logograms is their universal applicability – because they are language-independent – but and they have the obvious disadvantage that there must be a separate symbol for every word. logographic scripts | All complete writing systems the world has ever known, do effectively contain both logograms and 8.Syllabic phonograms. As purely pictorial ‘proto-scripts’ develop into ‘scripts’ or writing systems, naturally drawn scripts pictograms are stylised and augmented with drawings for abstract phenomena (hence called ideograms), | 9.Alphabetic and will ultimately contain logograms for all basic words of a specific language. -

Richard Parker

ON IN MEMORY OF YOUR OCCULT CONVOLUTIONS Richard Parker 317 GLOSSATOR 8 In Memory of Your Occult Convolutions1 1 Keston Sutherland’s ‘In Memory of Your Occult Convolutions’ was written for, and delivered at, a poetry reading organised to coincide with the 24th Ezra Pound Conference, London, July 5-9, 2011. The audience was predominantly made up of Pound scholars from around the world. The poem is constructed from excerpts from essays by Ezra Pound that deal with the relation of pedagogy to literature; ‘How to Read’ (1929), ‘The Serious Artist’ (1913), ‘The Teacher’s Mission’ (1934) and ‘The Constant Preaching to the Mob’ (1916). They are all collected, consecutively, in T.S. Eliot’s edition of the Literary Essays of Ezra Pound (1954) [hereafter LE]. Further extracts are taken from the poems ‘Fratres Minores’ (1914) and Homage to Sextus Propertius (1919), as well as Pound’s early critical work The Spirit of Romance (1910). The ‘Occult Convolutions’ of the title are taken from section 24 (of the 1892 version) of Walt Whitman’s ‘Song of Myself’. If I worship one thing more than another it shall be the spread of my own body, or any part of it, Translucent mould of me it shall be you! Shaded ledges and rests it shall be you! Firm masculine colter it shall be you! Whatever goes to the tilth of me it shall be you! You my rich blood! your milky stream pale strippings of my life! Breast that presses against other breasts it shall be you! My brain it shall be your occult convolutions! Root of wash’d sweet-flag! timorous pond-snipe! nest of guarded duplicate eggs! it shall be you! Mix’d tussled hay of head, beard, brawn, it shall be you! Trickling sap of maple, fibre of manly wheat, it shall be you! Sun so generous it shall be you! Vapors lighting and shading my face, it shall be you! You sweaty brooks and dews it shall be you! Winds whose soft-tickling genitals rub against me it shall be you! Broad muscular fields, branches of live oak, loving lounger in my winding paths, it shall be you! Hands I have taken, face I have kiss’d, mortal I have ever touch’d, it shall be you. -

Gained in Translation: Ezra Pound, Hu Shi, and Literary Revolution

Gained in Translation: Ezra Pound, Hu Shi, and Literary Revolution Jenine HEATON* I. Introduction Hu Shi 胡適( 1891-1962), Chinese philosopher, essayist, and diplomat, is well-known for his advocacy of literary reform for modern China. His article, “A Preliminary Discussion of Literary Reform,” which appeared in Xin Qingnian 新青年( The New Youth) magazine in January, 1917, proposed the radical idea of writing in vernacular Chinese rather than classical. Until Hu’s article was published, no reformers or revolutionaries had conceived of writing in anything other than classical Chinese. Hu’s literary revolution began with a poetic revolution, but quickly extended to literature in general, and then to expression of new ideas in all fi elds. Hu’s program offered a pragmatic means of improving communication, fostering social criticism, and reevaluating the importance of popular Chinese novels from past centuries. Hu Shi’s literary renaissance has been examined in great detail by many scholars; this paper traces the synergistic effect of ideas, people, and literary movements that informed Hu Shi’s successful literary and language revolu- tions. Hu Shi received a Boxer Indemnity grant to study agriculture at Cornell University in the United States in 1910. Two years later he changed his major to philosophy and literature, and after graduation, continued his education at Columbia University under John Dewey (1859-1952). Hu remained in the United States until 1917. Hu’s sojourn in America coincided with a literary revolution in English-language poetry called the Imagist movement that occurred in England and the United States between 1908 and 1917. Hu’s diaries indicate that he was fully aware of this movement, and was inspired by it. -

11 Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs 11

The Unicode® Standard Version 12.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2019 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 12.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-22-1 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode12.0.0/) 1.