A Probabilistic Model of Ancient Egyptian Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neural Substrates of Hanja (Logogram) and Hangul (Phonogram) Character Readings by Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Neuroscience http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.10.1416 • J Korean Med Sci 2014; 29: 1416-1424 Neural Substrates of Hanja (Logogram) and Hangul (Phonogram) Character Readings by Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Zang-Hee Cho,1 Nambeom Kim,1 The two basic scripts of the Korean writing system, Hanja (the logography of the traditional Sungbong Bae,2 Je-Geun Chi,1 Korean character) and Hangul (the more newer Korean alphabet), have been used together Chan-Woong Park,1 Seiji Ogawa,1,3 since the 14th century. While Hanja character has its own morphemic base, Hangul being and Young-Bo Kim1 purely phonemic without morphemic base. These two, therefore, have substantially different outcomes as a language as well as different neural responses. Based on these 1Neuroscience Research Institute, Gachon University, Incheon, Korea; 2Department of linguistic differences between Hanja and Hangul, we have launched two studies; first was Psychology, Yeungnam University, Kyongsan, Korea; to find differences in cortical activation when it is stimulated by Hanja and Hangul reading 3Kansei Fukushi Research Institute, Tohoku Fukushi to support the much discussed dual-route hypothesis of logographic and phonological University, Sendai, Japan routes in the brain by fMRI (Experiment 1). The second objective was to evaluate how Received: 14 February 2014 Hanja and Hangul affect comprehension, therefore, recognition memory, specifically the Accepted: 5 July 2014 effects of semantic transparency and morphemic clarity on memory consolidation and then related cortical activations, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) Address for Correspondence: (Experiment 2). The first fMRI experiment indicated relatively large areas of the brain are Young-Bo Kim, MD Department of Neuroscience and Neurosurgery, Gachon activated by Hanja reading compared to Hangul reading. -

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Emojis and Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs Emojis are often compared to Egyptian hieroglyphs because both use pictures to express meaning. However, Egyptian hieroglyphs were a writing system like the alphabet you are reading now and could be used to write anything. Instead of using letters for sounds, the ancient Egyptians used signs (pictures). Emojis are used differently. They add extra meaning to writing, a bit like how tone of voice and gestures add extra meaning when we’re speaking. You could write this paragraph using the emoji-alphabet at the top of the answer sheet, but that’s not how emojis are normally used. Aside from using signs instead of letters, there are lots of differences between the Scots and English writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one. For example, Egyptian hieroglyphs could be written either right to left or left to right and were often written in columns from top to bottom. Hieroglyphic writing didn’t use vowels. The name for this sort of writing system is an abjad. You can write out English and Scots with an abjad rather than an alphabet and still understand it without too much difficulty. For example: Ths sntnc sn’t vry hrd t rd. The biggest difference between alphabetic writing systems and the ancient Egyptian one is that in hieroglyphic writing a sign could be used in three ways. It could be used as a word (ideogram); as a sound (phonogram); or as an idea-sign (determinative) to make things easier to understand. For example, could be used as an ideogram for the word ‘bee’; as a phonogram for the first sound in ‘belief’; or as a determinative added to the end of the word ‘hive’ to distinguish it from ‘have’ and ‘heave’, which would all be written the same: hv. -

Determination in the Anatolian Hieroglyphic Script of the Empire and Transitional Period 223

Altorientalische Forschungen 2017; 44(2): 221–234 Annick Payne Determination in the Anatolian Hieroglyphic Script of the Empire and Transitional Period https://doi.org/10.1515/aofo-2017-0019 Abstract: The Anatolian Hieroglyphic script is a mixed writing system which contains both phonetic and semantographic signs. The latter may be used in the function of logogram and/or determinative. A dedicated study of the script’s determinatives has so far not been undertaken but promises insight into structures of mental organization and script development. Because of its pictorial character, individual signs can occasion- ally be shown to act in a dual capacity, as icons and signs of writing. This article forms part one of a diachronic study of the determinative system, and adresses the period 13th–10th century BC. Keywords: Ancient Anatolian writing systems, Anatolian Hieroglyphic script, determinatives Introduction In the Anatolian Hieroglyphic script (AH), determination is one function of the class of semantographic signs. Alternatively, semantographic signs may function as logograms. While logograms represent a word to be read out, determinatives are not intended to be read out, instead, they mark their host word as belonging to a specific semantic category. Thus, determinatives are mute graphemes that act as reading aids, and they are dependent on a host word; with very few exceptions,1 the determinative is placed in front of the host. Different relationships between determinative and host are possible: they may be coordinated or the host may be subordinate to a determinative representing a superordinate category under which several hosts may be subsumed. The script shows numerically equal relationships where one determinative is used for one host, with the aim of reinforcing – less frequently, obstructing – the reading, or of disambiguating it. -

Contents Foreword to the 2020 Edition Vii

Contents Foreword to the 2020 Edition vii Preface to the 2020 Edition viii LEM Phonics 2020: Change Summary ix SECTION ONE Introduction and Overview Phonics and English 2 Philosophy of Learning 5 LEM Phonics Overview 7 Phonological Awareness for Pre-Schoolers 9 The Stages of Literacy 12 Scope and Sequence of LEM Phonics 13 SECTION TWO The 77 Phonograms and 42 Sounds The 77 Phonograms 16 Single Phonograms 17 Multiple Phonograms 18 Successive Seventeen Phonograms 19 The 42 Sounds 20 Sounds and their Phonograms 22 SECTION THREE Handwriting 24 SECTION FOUR The Word List What is the WordSAMPLE List? 28 Word List Resources 30 Word List Student Activities 31 LEM Phonics Manual v SECTION FIVE The Rules Rules in LEM Phonics 34 The Rules: Guidelines and Reference 35 Guidelines for Teaching the Rules 36 Syllable Guidelines 40 Explanation Marks 43 Explanation Marks for Silent e 44 Rules Reference: Single Phonograms 45 Rules Reference: Multiple Phonograms 50 Rules Reference: Successive 17 Phonograms 55 Rules Reference: Teacher Book A 58 Rules Reference: Suffixes 62 SECTION SIX Supplementary Materials Games and Activities 68 Phonological Awareness Test 70 SAMPLE vi LEM Phonics Manual Phonics and English The History of English English is the most influential language in the world. It is also one of the most comprehensive with theOxford English Dictionary listing some 170,000 words in current common usage. Including scientific and technical terms the number swells to over one million words. To develop a comprehensive civilization requires a comprehensive language, which explains in part the worldwide influence English has enjoyed. English as we know it is a modern language which was first codified in 1755 in Samuel Johnson’sDictionary of the English Language. -

11 Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs 11

The Unicode® Standard Version 12.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2019 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 12.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-22-1 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode12.0.0/) 1. -

" King of Kish" in Pre-Sarogonic Sumer

"KING OF KISH" IN PRE-SAROGONIC SUMER* TOHRU MAEDA Waseda University 1 The title "king of Kish (lugal-kiski)," which was held by Sumerian rulers, seems to be regarded as holding hegemony over Sumer and Akkad. W. W. Hallo said, "There is, moreover, some evidence that at the very beginning of dynastic times, lower Mesopotamia did enjoy a measure of unity under the hegemony of Kish," and "long after Kish had ceased to be the seat of kingship, the title was employed to express hegemony over Sumer and Akked and ulti- mately came to signify or symbolize imperial, even universal, dominion."(1) I. J. Gelb held similar views.(2) The problem in question is divided into two points: 1) the hegemony of the city of Kish in early times, 2) the title "king of Kish" held by Sumerian rulers in later times. Even earlier, T. Jacobsen had largely expressed the same opinion, although his opinion differed in some detail from Hallo's.(3) Hallo described Kish's hegemony as the authority which maintained harmony between the cities of Sumer and Akkad in the First Early Dynastic period ("the Golden Age"). On the other hand, Jacobsen advocated that it was the kingship of Kish that brought about the breakdown of the older "primitive democracy" in the First Early Dynastic period and lead to the new pattern of rule, "primitive monarchy." Hallo seems to suggest that the Early Dynastic I period was not the period of a primitive community in which the "primitive democracy" was realized, but was the period of class society in which kingship or political power had already been formed. -

The Writing Revolution

9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iii The Writing Revolution Cuneiform to the Internet Amalia E. Gnanadesikan A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iv This edition first published 2009 © 2009 Amalia E. Gnanadesikan Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Amalia E. Gnanadesikan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. -

A Phonogram Based Word List for Reading and Spelling

A PHONOGRAM BASED WORD LIST FOR READING AND SPELLING Based on the Harris-Jacobson Basic Elementary Reading Vocabularies by ARDELLE LAURENE SCHOOLEY B. Ed., The University of British Columbia, 1968 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Language Education We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA JULY, 1982 ©Ardelle Laurene Schooley, 1982 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ^y^n^yy^T^P ^^SJtrtJsJtTtJ The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date oJ^^j^rrJs^cSn /<?8Z DE-6 (.3/81) ABSTRACT The purpose of the study was to reanalyze the graded word lists of the Harris-Jacobson Basic Elementary Reading Vocabularies according to phono• gram components to provide a phonogram-based word list in graded format. The methodology of the study required a three step process. First, all of the words of the Harris-Jacobson Basic Elementary Reading Vocabularies list were typed into a computer in grade level format. -

The Hieroglyphic Sign Functions. Suggestions for a Revised Taxonomy

The Hieroglyphic Sign Functions1 Suggestions for a Revised Taxonomy Stéphane Polis/Serge Rosmorduc Abstract The aim of this paper is to suggest a taxonomy that allows for a systematic description of the functions that can be fulfilled by hieroglyphic signs. Taking as a point of departure the insights of several studies that have been published on the topic since Champollion, we suggest that three key-features – namely, semography, phonemography and autonomy – are needed in order to provide a description of the glottic functions of the ancient Egyptian graphemes. Combining these paradigmatic and syntagmatic features, six core functions can be identified for the hieroglyphic signs: they may behave as pictograms, logograms, phonograms, classifiers, radicograms or interpretants. In a second step, we provide a defi nition for each function and discuss examples that illustrate the fuzziness between these core semiotic categories. The understanding of the functions of the signs2 in the hieroglyphic writing system3 has been an issue ever since knowledge of this script was lost during Late Antiquity. If ancient authors 1 We are grateful to Todd Gillen, Eitan Grossman, Matthias Müller, Wolfgang Schenkel, Sami Uljas and Jean Winand for their critical comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper. 2 In this paper, we focus exclusively on the so-called “glottic” functions (see e. g. Harris 2000) of the ancient Egyptian writing system, i. e., on the writing system viewed as a means of communicating linguistic content. It should be stressed that “[t]hat the notions of logograms, classifiers, phonograms, and interpretants [etc. used throughout this paper] refer to possible functions fulfilled by the tokens of particular graphemes according to their distribution and do not define inherent qualities of the signs” (Lincke/Kammerzell 2012: 59); see already Schenkel’s (1984: 714–718) and Kammerzell’s (2009) ‘Zeichenfunktionsklasse.’ 3 Regarding the various possible approaches to this complex writing system, see Schenkel (1971: 85). -

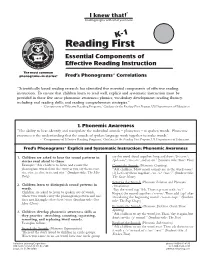

Reading First Program, US Department of Education Fred’S Phonograms® Explicit and Systematic Instruction: Reading Fluency K-1 1

® 4. Reading Fluency, Oral Reading Skills I knew that! “Fluency is the ability to read text accurately and quickly. It provides a bridge between word recognition and comprehen- Reading begins with what you know. sion. Fluent readers recognize words and comprehend at the same time.” - “Components of Effective Reading Programs,”Guidance for the Reading First Program, US Department of Education Fred’s Phonograms® Explicit and Systematic Instruction: Reading Fluency K-1 1. Phonogram words are featured in story contexts, 3. Phonogram words appear in consistent sound- with repetitive text and supportive illustrations. and-letter patterns throughout the stories. Reading First Text example from student title, The Black Shack, follows. Consistent word patterns promote the development of decoding skills and reinforce accuracy. These acquired The Black Shack skills go beyond the pattern, expanding the reach of Essential Components of The tack came off. decoding skills. The rack came off. Effective Reading Instruction The pack came off. 4. Broad reading levels promote the development of Crack! reading fluency. The most common The bear fell back ® Twelve progressive reading levels are included in the phonograms—in stories! Fred’s Phonograms Correlations and lost his snack. series of student books. Quack! Quack! Quack! 5. Reading activities include read-aloud, small group, “Scientifically based reading research has identified five essential components of effective reading 2. Rhymes reinforce rimes! individual, pairs, and silent reading. Phonograms, also known as rimes, in rhyming patterns instruction. To ensure that children learn to read well, explicit and systematic instruction must be Classroom activities are tailored for each student title. invite children into the story. -

OLD AKKADIAN WRITING and GRAMMAR Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu OLD AKKADIAN WRITING AND GRAMMAR oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu MATERIALS FOR THE ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY NO. 2 OLD AKKADIAN WRITING AND GRAMMAR BY I. J. GELB SECOND EDITION, REVISED and ENLARGED THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada c, 1952 and 1961 by The University of Chicago. Published 1952. Second Edition Published 1961. PHOTOLITHOPRINTED BY GUSHING - MALLOY, INC. ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 1961 oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS pages I. INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF OLD AKKADIAN 1-19 A. Definition of Old Akkadian 1. B. Pre-Sargonic Sources 1 C. Sargonic Sources 6 D. Ur III Sources 16 II. OLD AKKADIAN WRITING 20-118 A. Logograms 20 B. Syllabo grams 23 1. Writing of Vowels, "Weak" Consonants, and the Like 24 2. Writing of Stops and Sibilants 28 3. General Remarks 4o C. Auxiliary Marks 43 D. Signs 45 E. Syllabary 46 III. GRAMMAR OF OLD AKKADIAN 119-192 A. Phonology 119 1. Consonants 119 2. Semi-vowels 122 3. Vowels and Diphthongs 123 B. Pronouns 127 1. Personal Pronouns 127 a. Independent 127 b. Suffixal 128 i. With Nouns 128 ii. With Verbs 130 2. Demonstrative Pronouns 132 3. 'Determinative-Relative-Indefinite Pronouns 133 4. Comparative Discussion 134 5. Possessive Pronoun 136 6. Interrogative Pronouns 136 7. Indefinite Pronoun 137 oi.uchicago.edu pages C. Nouns 137 1. Declension 137 a. Gender 137 b. Number 138 c. Case Endings- 139 d.