On the Origin of Alphabetic Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

History of the Alphabet

History of the Western European Alphabet We’re going to take a look at the evolution of symbols and systems of writing that have become the the letterforms we use today. This survey includes pictographs, cunieforms, hieroglyphics, and Roman Monumental Capitals. My hope in sharing this information with you is that we gain an appreciation for the history and the design of the alphabet, In the book Alphabet: The History, Evolution, and Design and that we do not take these of the Letters We Use Today, Allan Haley writes: letterforms for granted. “Writing is words made visible. The evolution of letterforms In the broadest sense, it is and a system of writing has everything—pictured, drawn, been propelled by our need to represent things, to represent or arranged—that can be turned ideas, to record and preserve into a spoken account. The information, and to express ourselves. For thousands of fundamental purpose of writing years a variety of imaging, is to convey ideas. Our ancestors, tools, and techniques have however, were designers long been used. Marks were made on cave walls, scraped and before they were writers, and stamped into clay, carved in in their pictures, drawings, and stone, and inked on papyrus. arrangements, design played a prominent role in communication from the very beginning”. Cave Painting from Lascaux, 15,000-10,000 BC One of the earliest forms of visual communication is found in cave paintings. The cave paintings found in Lascaux, France are dated from 10,000 to 8000 BC. These images are referred to as pictographs. Pictographs are a concrete representation of an object in the physical world. -

A Ugaritic Abecedary and the Origins of the Proto-Canaanite Alphabet

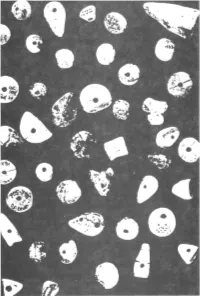

51 A Ugaritic Abecedary and the Origins of the Proto-Canaanite Alphabet [1960] FRANK MOORE CROSS AND THOMAS 0. LAMBDIN Advances in the decipherment of Proto-Canaanite pictograph to Phoenician letter in deciphered contexts. 4 texts during the past twelve years, 1 together with the dis Five others, whose pictographs remain more or less ob covery of the 'El-{Ja<;lr arrowheads in 1953, 2 have fur scure, can also be traced from pictograph to conventional nished definitive evidence that the Linear Phoenician sign, making a total of some seventeen of twenty-two alphabet3 evolved directly from the Proto-Canaanite pic signs whose historical typology is now clear. 5 With the tographic script. Twelve of the most frequent signs can be establishment of this evolution, there appears to be no es traced in detail through their evolution from transparent cape from the conclusion that the Proto-Canaanite alpha betic system has its beginnings in an acrophonically 1. See W. F. Albright, "The Early Alphabetic Inscriptions from Si devised script under direct or indirect Egyptian influence, nai and their Decipherment," BASOR 110 ( 1948): 6-22; and especially somewhere in Syria-Palestine. Further, it was reasonable, The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions and Their Decipherment (HTS 22; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966). See also F. M. if not necessary, to argue on the basis of these data that the Cross, "The Evolution of the Proto-Canaanite Alphabet," BASOR 134 names of the individual signs, and probably the order of (1954): 15-24 [Paper 50 above]. the signs as well, went back in principle to the time of the 2. -

The Writing Revolution

9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iii The Writing Revolution Cuneiform to the Internet Amalia E. Gnanadesikan A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iv This edition first published 2009 © 2009 Amalia E. Gnanadesikan Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Amalia E. Gnanadesikan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Reading from A to Z: The Alphabetic Sequence in Experimental Literature and Visual Art Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/10m9712j Author Ardam, Jacquelyn Wendy Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading from A to Z: The Alphabetic Sequence in Experimental Literature and Visual Art A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Jacquelyn Wendy Ardam 2015 © Copyright by Jacquelyn Wendy Ardam 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading from A to Z: The Alphabetic Sequence in Experimental Literature and Visual Art by Jacquelyn Wendy Ardam Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Michael A. North, Chair “Reading from A to Z” argues for the significance of the alphabetic sequence to the transatlantic experimental literature and visual art from the modern period to the present. While it may be most familiar to us as a didactic device to instruct children, various experimental writers and avant-gardists have used the alphabetic sequence to structure some of their most radical work. The alphabetic sequence is a culturally-meaningful trope with great symbolic import; we are, after all, initiated into written discourse by learning our ABCs, and the sequence signifies logic, sense, and an encyclopedic and linear way of thinking about and representing the world. But the string of twenty-six arbitrary signifiers also represents rationality’s complete opposite; the alphabet is just as potent a symbol and technology of nonsense, arbitrariness, and (children’s) play. -

Repo R T R E S U M E S Ed 013 818 24 Te Odd 060 a Curriculum for English ; Student Packet, Grace 7

REPO R T R E S U M E S ED 013 818 24 TE ODD 060 A CURRICULUM FOR ENGLISH ; STUDENT PACKET, GRACE 7. NEBRASKA UNIV., LINCOLN,CURRICULUM DEV. CTR. PUB DATE 65 CONTRACT OEC-2-10-119 EDRS PRICE MF-$1.00 HCNOT AVAILABLE rROM MRS. 258F. DESCRIPTORS- *CURR/CULUM GUIDES,*ENGLISH CURRICULUM, *ENGLISH INSTRUCTION, *GRADE 7,*INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS, COMPOSIIION (LITERARY), LINGUISTICS,LITERATURE, LANGUAGE, LITERARY ANALYSIS, MYTHOLOGY, SPELLING,SHORT STORIES; FORM CLASSES (LANGUAGES), DICTIONARIES,NEBRASKA CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT CENTER THE SEVENTH-GRADE STUDENTPACKET, PRODUCED BY THE NE9RASKA CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENTCENTER, BEGINS WITH THEUNIT ENTITLED "THE MAKING OF STORIES"IN WHICH STUDENTS CONSIDER WRITERS' AUDIENCES AND METHODSCF COMPOSITION AND PRESENTATION. SUCH MATERIAL AS "ACHRISTMAS CAROL" AND SELECTIONS FROM "THE ODYSSEY,""BEOWULF," "HYMN TO HERMES," AND GRIMM'S "FAIRY TALES"ARE STUDIED TO SHOW THEDIFFERENT SETS Cf CONDITIONS UNDERWHICH AUTHORS "MAKE UF"STORIES. A RELATED UNIT, "THE MEANING OFSTORIES," ATTEMPTS TO TEACH STUDENTS, THROUGH POEMS ANDSTORIES, TO ASK WHAT A STORY MEANS AND FICAd THE MEANING ISCOMMUNICATED. WITH THIS BACKGROUND, STUDENTS ARE PREPAREDTO STUDY SELECTIONS IN THREE UNITS ON MYTHOLOGYGREEKMYTHS; HECREW LITERATURE,AND AMERICAN INDIAN MYTHS. IN THEFOLLOWING UNIT, STUDENTS ENCOUNTER BALLADS, AMERICANFOLKLORE, AND A WESTERN NOVEL, "SHANE." THE FINAL LITERATUREUNIT, "AUTOBIOGRAPHYBENJAMIN FRANKLIN," IS DESIGNED FOR THESTUDY Cf A LITERARY GENRE AND THE WRITING OF PERSONALAUTOBIOGRAPHIES. IN THE LANGUAGE UNITS, STUDENTS STUDY FORMS OFWORDS AND POSITIONS Cf WORDS IN SENTENCES, THE ORGANIZATIONAND USE CF THE DICTIONARY,AND METHODS OF SOLVING INDIVIDUALSPELLING PROBLEMS. UNITS CONTAIN OVERVIEWS OF MATERIALTO OE STUDIED, DISCUSSIONS Of LITERARY GENRES, HISTORICALBACKGROUNDS OF WORKS, STUDY AND DISCUSSION QUESTIONS, COMPOSITIONASSIGNMENTS, EXERCISES; SUPPLEMENTARY READING LISTS, VOCABULARYLISTS, AND GLOSSARIES. -

The Origin and Transmission of the Alphabet

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 1994 The Origin and Transmission of the Alphabet Joaquim Azevedo Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Azevedo, Joaquim, "The Origin and Transmission of the Alphabet" (1994). Master's Theses. 28. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/28 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be firom any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photogrsq>hs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Alphabetic Literacy and Brain Processes

274 Visible Language XX 3 Summer 1986 HLPHRBETI C L ITERHCY RND IRR IN PROCESSES Derrick de Kerckhove The University of Toronto Several relationships are explored in this paper to support the hypothesis that writ ing systems affect cognitive strategies at a deeper level of human information processing thatn is generally accepted in present-day psychology. It appears reasonable to claim that the structure of orthographies is strongly correlated with the specific linguistic features of the languages they represent. The Greek alphabet developed in the high density area of different Mediterranean cultures and its lineage combines features of the Sumerian and the Egyptian scripts. However, it was worked out as an adaptation to the specific needs of the Greek language. The word "alphabet" presents enough ambiguity to warrant a category distinction bet ween consonantal and vocalic types of alphabetic systems. Both types require differ ent processing strategies. Among the indicators of such differences, it has been observed that both orthographies adopted different orientations. In almost all var ieties of alphabets and syllabaries, consonantal systems have been written leftwards while vocalic ones have been written to the right. Why? The answer to this question may be found in different neurophysiological constraints imposed to the brain by different types of orthographies. The object of this paper is to raise a basic question concerning the underpinnings of the Western culture. Did the fully phonetic al phabet invented by the Greeks circa 740 B.C. (for a discussion of a possibly earlier date, see Naveh, 1982) and still used today in Greece (and in the rest of the West in its latinized version) have a condition ing impact on the biases of specialized brain processes in our culture? Could the alphabet have acted on our brain as a powerful computer language, determining or emphasizing the selection of some of our perceptual and cognitive processes? This question has already been raised in terms of hemispheric specialization by Joseph Bogen (1975, p. -

UC Berkeley Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society

UC Berkeley Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society Title Writing in the World and Linguistics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7vv3w7p8 Journal Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 36(36) ISSN 2377-1666 Author Daniels, Peter T Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY SIXTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BERKELEY LINGUISTICS SOCIETY February 6-7, 2010 General Session Special Session Language Isolates and Orphans Parasession Writing Systems and Orthography Editors Nicholas Rolle Jeremy Steffman John Sylak-Glassman Berkeley Linguistics Society Berkeley, CA, USA Berkeley Linguistics Society University of California, Berkeley Department of Linguistics 1203 Dwinelle Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-2650 USA All papers copyright c 2016 by the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 0363-2946 LCCN: 76-640143 Contents Acknowledgments v Foreword vii Basque Genitive Case and Multiple Checking Xabier Artiagoitia . 1 Language Isolates and Their History, or, What's Weird, Anyway? Lyle Campbell . 16 Putting and Taking Events in Mandarin Chinese Jidong Chen . 32 Orthography Shapes Semantic and Phonological Activation in Reading Hui-Wen Cheng and Catherine L. Caldwell-Harris . 46 Writing in the World and Linguistics Peter T. Daniels . 61 When is Orthography Not Just Orthography? The Case of the Novgorod Birchbark Letters Andrew Dombrowski . 91 Gesture-to-Speech Mismatch in the Construction of Problem Solving Insight J.T.E. Elms . 101 Semantically-Oriented Vowel Reduction in an Amazonian Language Caleb Everett . 116 Universals in the Visual-Kinesthetic Modality: Politeness Marking Features in Japanese Sign Language (JSL) Johnny George . -

Contents Introduction • Bringing Global Cultures and World Languages Into K-8 Classrooms: Manual for Language and Culture Book Kits

Contents Introduction • Bringing Global Cultures and World Languages into K-8 Classrooms: Manual for Language and Culture Book Kits . 2 • Guidelines for Language and Culture Book Kits . 4 • Evaluating Authenticity. 5 • Global and Intercultural Understanding . 6 • Critical Inquiry and Global Literature .. 7 • Begler Model – Global Culture: First Steps toward Understanding . 8 • Rubric: Global Competencies . 13 • Rubric: Student Friendly Global Competencies . 14 • Rubric: “I can . .” Global Competencies . .. 15 Strategies for Responding to Literature • Critically Reading the Word and the World . 17 • Literature Circles with information on shared texts . 27 • Overview of Strategies . 32 • Cultural X-Rays . 34 • Save the Last Word for Me . 37 • Sketch-to-Stretch. 39 • Consensus Board. .41 • Venn Diagrams . .43 Teacher Vignettes • Encouraging Reflection through Graffiti Boards and Literature Circles. .44 • Engaging Students with the Unfamiliar .. .51 • Exploring Culture through Literature Written in Unfamiliar Languages. .58 • Mapping Our Understanding . .67 • Encouraging Symbolic Thinking Through Literature . .73 • Encouraging Intertextual Thinking in the Classroom . .81 • Exploring Flow Charts as a Tool for Thinking . .94 • Creating a Context for Understanding in Literature Circles. .104 Resources • Annotated Book Lists Arabi . .112 Korean . .116 • Maps . .123 • Web Sites . 160 • Language Information .. 162 Bringing Global Cultures and World Languages into K-8 Classrooms: Manual for Language and Culture Book Kits Most U.S. students do not encounter less commonly taught languages until they enter high school or the university. Our goal is to introduce K-8 students to less commonly taught cultures and languages so that students will be more open to later choosing that language for study and are more comfortable with exploring a range of world languages and global cultures. -

Runes Pdf, Epub, Ebook

RUNES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Findell | 112 pages | 24 Mar 2014 | BRITISH MUSEUM PRESS | 9780714180298 | English | London, United Kingdom Runes PDF Book By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Notice. Runecasting Aspects - When should a rune be read as "reversed" or "merkstave"? If anyone objects to my use of anything on this site, please contact me, and I will take care of it right away. The Uthark theory originally was proposed as a scholarly hypothesis by Sigurd Agrell in Bonfante, The Etruscan Language p. The reduction correlates with phonetic changes when Proto-Norse evolved into Old Norse. Makaev, who presumes a "special runic koine ", an early "literary Germanic" employed by the entire Late Common Germanic linguistic community after the separation of Gothic 2nd to 5th centuries , while the spoken dialects may already have been more diverse. Little is known about the origins of the Runic alphabet, which is traditionally known as futhark after the first six letters. These inscriptions are generally in Elder Futhark , but the set of letter shapes and bindrunes employed is far from standardized. The runes had magical and sacral significance. Notably, more than inscriptions using these runes have been discovered in Bergen since the s, mostly on wooden sticks the so-called Bryggen inscriptions. The names are clearly Gothic, but it is impossible to say whether they are as old as the letters themselves. Nevertheless, it has proven difficult to find unambiguous traces of runic "oracles": although Norse literature is full of references to runes, it nowhere contains specific instructions on divination. History of the alphabet Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. -

Wheels of Fortune: the Alphabet 99

WHEELS OF FORTUNE: THE ALPHABET 99 a non-empire and an outward-looking, migratory society helped 5 it to take this step of logical abstraction and communicative Wheels of Fortune: The Alphabet economy based on the neigh boring accomplishments of cuneiform and hieroglyphic. The earlier writing systems of Mesopotamia and Egypt were indeed the first, the basis of the advance to follow. Those two systems contained hundreds of signs based on pictorial representation in the case of hieroglyphic and a syllabic principle in It may be a surprise to realize that the letters I am using now, in the case of cuneiform-somewhat cumbersome and limited in use fact the letters people use and teach their children to use, or the to specialized scribes. The novel idea was to find a sort of sound ones they guess on the TV show "Wheel of Fortune," originated in shorthand, just the right number of signs to represent the spoken the East Mediterranean region more than 3500 years ago at a time language efficiently. when the people living there were Canaanites, We don't know where exactly in Cana 'an the alphabet first Yet, as I explain in Chapter 1, while Canaan is idealized as a originated-though Jubayl in Lebanon (ancientJubla; Greek Byblos) land of great bounty, the Cana'anites themselves (generalized as C, or a location in southern Palestine is most likely. Southern Palestine, the Other) are demonized as a people-a prerequisite for justifying near the borders of Egypt, 'seems the more probable geography, in why they (and others) could be slaughtered and dispossessed of their view of the discovery of a proto-alphabet at Serabit el Khadim, a lands.