UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eunoia: the Good Bök - Times Online 21/11/08 5:14 PM

Eunoia: The good Bök - Times Online 21/11/08 5:14 PM Credit Munch Get 20% off your bill at Pizza Express Britain's still paying a heavy price for misjudgments in the inter-war years Libby Purves NEWS COMMENT BUSINESS MONEY SPORT LIFE & STYLE TRAVEL DRIVING ARTS & ENTS VIDEO ARCHIVE OUR PAPERS FILM MUSIC STAGE VISUAL ARTS TV & RADIO WHAT'S ON BOOKS THE TLS GAMES & PUZZLES Where am I? Home Arts & Entertainment Books Times Online From The Times MY PROFILE SHOP JOBS PROPERTY CLASSIFIEDS November 14, 2008 MOST READ MOST COMMENTED MOST CURIOUS Eunoia: The good Bök TODAY Horror as teenager commits suicide live... Giles Whittell meets Christian Bök, the Canadian writer behind Briton found guilty of throwing lover off... Eunoia, the univocal bestseller Business big shot: Arianna Huffington,... Somali pirates seize ninth vessel in 12 days EXPLORE BOOKS BOOK EXTRACTS BOOK REVIEWS BOOKS GROUP AUDIO BOOKS TIMES RECOMMENDS And the Hippos were Boiled in their Tanks by William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac Sci-fi: Little Brother by Cory DURING THE SEVEN YEARS it took Christian Bök to write Doctorow and The Quiet War Eunoia he would often read to audiences from his work in by Paul McAuley progress. He preferred not to tell them what was coming so that he could see the look on their faces when they realised what was happening. REVIEW “It would suddenly start dawning on people that I was performing this very athletic and acrobatic feat,” he says. “You could see the FOCUS ZONE light bulbs going on.” Listeners' first instinct would be to “wait for the moment of failure, Social Entrepreneurs: to see where I had screwed up. -

Guide Pédagogique 08 EN

THE LIPOGRAM Fin de soirée , de Tristan Bastit Info Sheet Jeux de mots: 7th Blue Metropolis Lipogram Contest _______________________________________________ By EVE PARISEAU What is a lipogram? Lipograms are literary word games in which the writer intentionally avoids using one or more letters of the alphabet. In 1969, the great French writer Georges Perec wrote an entire novel, La Disparition , without using the letter e. Up for the challenge? A Brief Description of the Activity SECOND ACTIVITY Working with lipograms provides an excellent LIPOGRAM WORKSHOP opportunity for integrating creative writing and word play into classroom work. Lipograms, with the formal Activity Description constraints they place on which words can be used, Students search—with or without a dictionary, alone or encourage students to explore the limits of language. in groups—lipogrammatic words (words without a certain vowel) having to do with a defined subject, and Educational Goals which can replace other words. Since this is the second The proposed activities are aimed at meeting goals for exercise, the teacher may want to choose vowels less writing, reading and oral expression in poetry and constraining than the “e”. narrative. The students’ grammatical abilities, spelling and syntax, and their lexical and semantic development, Educational Goals will be put to the test, as well as their ability to work with Develop the students’ lexical skills humour. The challenges of the lipogram have a natural Develop lexical fields teaching effect. Familiarize students with lipograms What’s Needed Time Required The understanding of a few basic concepts is required A half-session for the student to participate. -

On the Origin of Alphabetic Writing

Aren M. Wilson-Wright Radboud University, Nijmegen November 2019 On the Origin of Alphabetic Writing Over the past few years, several scholars have advanced new theories regarding the origin of the alphabetic writing. Douglas Petrovich (2016) and Paul LeBlanc (2017), for example, both argue that the ancient Israelites invented the alphabet during their sojourn in Egypt.1 And in a 2019 article for Bible and Interpretation, Robert Holmstedt suggests that the inhabitants of Byblos developed the alphabet from the earlier Byblos Script, an undeciphered writing system found at the Phoenician city of Byblos. As part of this article, he articulates several important questions about the invention of the alphabetic writing that should guide all future inquiries into the topic: Who invented the alphabet? Where did they come from? Were they familiar with any of the other writing systems used in the ancient Near East? In this article, I will review the inscriptional and historical data that can help us answer these questions, evaluate Holmstedt’s arguments, and present my own theory of alphabetic origins. I. Review of the Evidence The earliest alphabetic inscriptions furnish the primary evidence regarding the invention of the alphabet. These inscriptions come from the Egyptian sites of Serabit el-Khadem and Wadi el-Ḥôl (see map). In 1905, Sir Flinders Petrie (1906: 129–30) discovered ten early alphabetic inscriptions while excavating the Egyptian temple and turquoise mining facility at Serabit el-Khadem. Subsequent excavations at Serabit el-Khadem—from 1920s to the 2000s—have uncovered an additional 37 early alphabetic inscriptions (Lindblom 1931; Butin 1932; Starr and Butin 1936; Gerster 1961: pl. -

Christian Bök (1966 — ) Is a Professor at the University of Calgary, and He Is the Author of Two Books of Poetry

Parliamentary Poet Laureate POETRY CONNECTION: LINK UP WITH CANADIAN POETRY Christian Bök (1966 — ) is a professor at the University of Calgary, and he is the author of two books of poetry. Crystallography (Coach House, 1994) has been nominated for the Gerald Lampert Award for Best Poetic Debut, and Eunoia (Coach House, 2001) has won the 2002 Griffin Poetry Prize, becoming a bestseller in Canada and the UK. Eunoia consists of five chapters (each of which tells a story, using words that contain only one of the five vowels). Bök has also published a book of critical writing, entitled ‘Pataphysics: The Poetics of an Imaginary Science (Northwestern University Press, 2001). Bök has created artificial languages for two TV shows: Gene Roddenberry’s Earth: Final Conflict and Peter Benchley’s Amazon. He has also exhibited artworks in galleries around the world. Poem for discussion: “The Perfect Malware” is a selection from an ongoing project, entitled The Xenotext, a transgenic artwork that Bök has been creating for the last 11 years at a cost of $120,000. Bök has written two poems that mutually encode each another (e.g., the word “lyre” in one poem translates to “rely” in the other, with L assigned to R and E assigned to Y). Bök has encoded the first poem as a sequence of DNA implanted into a bacterium. The lifeform then “reads” this poem, as part of its normal biological processes, and then the lifeform “writes” the second poem, encoding it into a sequence of amino acids that make up a protein. Bök is quite literally writing a living poem. -

A Moma Sestina

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 77 CutBank 77 Article 38 Fall 2012 Eunoia Eye to Eye: A MoMa Sestina Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingde Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Zhicheng-Mingde, Desmond Kon (2012) "Eunoia Eye to Eye: A MoMa Sestina," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 77 , Article 38. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss77/38 This Poetry is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DESMOND KON Z H I C H E N G-M I N G D E EUNOIA EYE TO EYE: A MOMA SESTINA The wheelmen, when wet, wrest the wheel. — Christian Bok Eunoia, this is not a new aesthetic or epistemology about beauty, what ends undergird Wittgenstein’s wit, pronouncements of logic, any subject under Novalis and this noonday sky, of the theory of symbolism trumping names, of the theory of types being categorical squares, pointy corners overlapping, inward spiral into an nth number of trapezoids colliding, more intoned inside, artifice as objects seen sub specie aeternitatis, happy despite eulogies and euphemisms, or toasting revisioned lives, what possibility got shored up and unraveled, red mountain of origami tigers dissolved in acid rain, timed to end November, feast days from St. Martin’s to the long road home, -

On Writing Lipograms

33 ON WRITING LIPOGRAMS ROBERT CASS KELLER e changed Why is it that writers usually OITlit E, the ITlost COITlITlOn letter in word? English text, when creating a literary lipograITl? I believe that this and LIER tendency has been reinforced by the existence of the only book-length English-language lipograITl, Ernest V. Wright's E-less novel, Gadsby (Wetzel, Los Angeles, 1939). In fact, its influence ITlay have extend ination ed even to France. OuLiPo ITleITlber Georges Perec constructed La ,ilarly, Disparation (Denoel, Paris, 1969) without using the letter E; SOITle of the book's reviewers did not even realize that it was a lipograITl! rage Obviously, oITlitting any other letter should ITlake the lipograITlITla tic task easier. To restore balance, I propose that a lipograITl ought twice as to be constructed oITlitting as ITlany letters of the alphabet as possible. cry. In Throwing away the rarest letters first, how ITlany can be eliITlinated Answers before the task of writing with the reITlainder is cOITlparable to a ITlis sing E? A first answer to this question can be given by' reITloving let ters which collectively have the frequency of E in English text -- the eleven letters ZQJXKVBYGWP. When constructing a lipograITl, short words are ITlore valuable ,ate than long ones, for it is likely that ITlost long words will be eliITlinated ard no ITlatter what letters are thrown away. If a given alphabetic letter is ITlore prevalent in short words than long one s, this letter ought not heavily to be reITloved. For exaITlple, the rather rare letter W is concentrated iITl in several COITlITlon short words, such as WAS, WITH, WHERE, WERE, :lal WHEN and WILL; F occurs in the very COITlITlon OF, FOR and FROM. -

Serious Play: Formal Innovation and Politics in French Literature from the 1950S to the Present

Serious Play: Formal Innovation and Politics in French Literature from the 1950s to the Present by Aubrey Ann Gabel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Professor Debarati Sanyal Professor C.D. Blanton Professor Mairi McLaughlin Summer 2017 Abstract Serious Play: Formal Innovation and Politics in French Literature from the 1950s to the Present By Aubrey Ann Gabel Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Serious Play: Formal Innovation and Politics in French literature from the 1950s to the present investigates how 20th- and 21st-century French authors play with literary form as a means of engaging with contemporary history and politics. Authors like Georges Perec, Monique Wittig, and Jacques Jouet often treat the practice of writing like a game with fixed rules, imposing constraints on when, where, or how they write. They play with literary form by eliminating letters and pronouns; by using only certain genders, or by writing in specific times and spaces. While such alterations of the French language may appear strange or even trivial, by experimenting with new language systems, these authors probe into how political subjects—both individual and collective—are formed in language. The meticulous way in which they approach form challenges unspoken assumptions about which cultural practices are granted political authority and by whom. This investigation is grounded in specific historical circumstances: the student worker- strike of May ’68 and the Algerian War, the rise of and competition between early feminist collectives, and the failure of communism and the rise of the right-wing extremism in 21st-century France. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

History of the Alphabet

History of the Western European Alphabet We’re going to take a look at the evolution of symbols and systems of writing that have become the the letterforms we use today. This survey includes pictographs, cunieforms, hieroglyphics, and Roman Monumental Capitals. My hope in sharing this information with you is that we gain an appreciation for the history and the design of the alphabet, In the book Alphabet: The History, Evolution, and Design and that we do not take these of the Letters We Use Today, Allan Haley writes: letterforms for granted. “Writing is words made visible. The evolution of letterforms In the broadest sense, it is and a system of writing has everything—pictured, drawn, been propelled by our need to represent things, to represent or arranged—that can be turned ideas, to record and preserve into a spoken account. The information, and to express ourselves. For thousands of fundamental purpose of writing years a variety of imaging, is to convey ideas. Our ancestors, tools, and techniques have however, were designers long been used. Marks were made on cave walls, scraped and before they were writers, and stamped into clay, carved in in their pictures, drawings, and stone, and inked on papyrus. arrangements, design played a prominent role in communication from the very beginning”. Cave Painting from Lascaux, 15,000-10,000 BC One of the earliest forms of visual communication is found in cave paintings. The cave paintings found in Lascaux, France are dated from 10,000 to 8000 BC. These images are referred to as pictographs. Pictographs are a concrete representation of an object in the physical world. -

A Ugaritic Abecedary and the Origins of the Proto-Canaanite Alphabet

51 A Ugaritic Abecedary and the Origins of the Proto-Canaanite Alphabet [1960] FRANK MOORE CROSS AND THOMAS 0. LAMBDIN Advances in the decipherment of Proto-Canaanite pictograph to Phoenician letter in deciphered contexts. 4 texts during the past twelve years, 1 together with the dis Five others, whose pictographs remain more or less ob covery of the 'El-{Ja<;lr arrowheads in 1953, 2 have fur scure, can also be traced from pictograph to conventional nished definitive evidence that the Linear Phoenician sign, making a total of some seventeen of twenty-two alphabet3 evolved directly from the Proto-Canaanite pic signs whose historical typology is now clear. 5 With the tographic script. Twelve of the most frequent signs can be establishment of this evolution, there appears to be no es traced in detail through their evolution from transparent cape from the conclusion that the Proto-Canaanite alpha betic system has its beginnings in an acrophonically 1. See W. F. Albright, "The Early Alphabetic Inscriptions from Si devised script under direct or indirect Egyptian influence, nai and their Decipherment," BASOR 110 ( 1948): 6-22; and especially somewhere in Syria-Palestine. Further, it was reasonable, The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions and Their Decipherment (HTS 22; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966). See also F. M. if not necessary, to argue on the basis of these data that the Cross, "The Evolution of the Proto-Canaanite Alphabet," BASOR 134 names of the individual signs, and probably the order of (1954): 15-24 [Paper 50 above]. the signs as well, went back in principle to the time of the 2. -

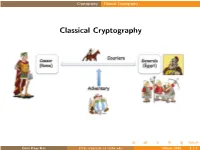

` `%%%`#`&12 `__~~~Classical Cryptography

Cryptography Classical Cryptography Classical Cryptography C¸etin Kaya Ko¸c http://koclab.cs.ucsb.edu Winter 2016 1 / 1 Cryptography Classical Cryptography Shift Cipher Input/output: {a, b,..., z} with encoding {0, 1,..., 25} a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 p q r s t u v w x y z 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Encryption function: Ek (x)= x + k (mod 26) Decryption function: Dk (y)= y − k (mod 26) The encryption or decryption key: k ∈ {0, 1, 2,..., 25} Key space size: 26 (or 25, if you do not count k = 0) Caesar cipher: Shift cipher with a constant encryption key k = 3 C¸etin Kaya Ko¸c http://koclab.cs.ucsb.edu Winter 2016 2 / 1 Cryptography Classical Cryptography Shift Cipher For k = 15, hello is encrypted as wtaad since E15(h)= E15(7) = 7 + 15 = 22 (mod 26) → w E15(e)= E15(4) = 4 + 15 = 19 (mod 26) → t E15(l)= E15(11) = 11 + 15 = 26 = 0 (mod 26) → a E15(o)= E15(14) = 14 + 15 = 29 = 3 (mod 26) → d For k = 12, eqqw is decrypted as seek since D12(e)= D12(4) = 4 − 12 = −8 = 18 (mod 26) → s D12(q)= D12(16) = 16 − 12 = 4 (mod 26) → e D12(w)= D12(22) = 22 − 12 = 10 (mod 26) → k C¸etin Kaya Ko¸c http://koclab.cs.ucsb.edu Winter 2016 3 / 1 Cryptography Classical Cryptography Cryptanalysis of Shift Cipher Ciphertext only (CO) Exhaustive key search: a paragraph of ciphertext (in order to avoid ambiguity) Frequency analysis: a paragraph of ciphertext (in order to get statistically reliable frequency count) Known plaintext (KP): a single plaintext/ciphertext pair Chosen plaintext (CP): a single plaintext/ciphertext -

The Meaning Revealed at the Nth Degree in Christian Bök's Eunoia

The Meaning Revealed at the Nth Degree in Christian Bök’s Eunoia Sean Braune hristian Bök is one of the foremost Canadian poets of the avant-garde. During a conversation between Bök and Darren Wershler-Henry for Brick, Wershler-Henry noted that Eunoia Cis the fastest selling book of poetry since Robert Service’s Songs of a Sourdough (119). The book’s success has left Bök baffled: “I wonder sometimes whether or not people are simply reading it because of its freakish character, passing by it like a carload of vacationers, slowing down to gawk at a two-headed calf by the side of the road” (Brick 120). Its success is indeed surprising because of the work’s experiment- al nature and avant-garde status. Experimental literature is typically not commercially fruitful, which makes the success of Eunoia all the more surprising. Perhaps Bök is correct when he compares his work to a “two-headed calf” because of its peculiar success. The book’s formid- able structural constraint requires a gloss or “skeleton key” to assist in approaching and decoding the work. This essay is intended to facilitate such an approach. The obsessive construction of Eunoia is influenced by the textual constraints of the French literary group called the “Oulipo.”1 The Oulipo was a “workshop” where many prominent French writers met to discuss the possibility of producing texts without the aid of “inspira- tion.” Rather than rely on a “lightning bolt” of inspiration to strike, the Oulipians invented mathematical constraints that could produce litera- ture with or without the aid of a writer.2 These constraints can be seen in the syntactical parallelism, internal rhyme schemes, and the inverse- lipogram3 of the book’s textual structure.