3 Writing Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Similarities and Dissimilarities of English and Arabic Alphabets in Phonetic and Phonology: a Comparative Study

Similarities and dissimilarities of English and Arabic 94 Similarities and dissimilarities of English and Arabic Alphabets in Phonetic and Phonology: A Comparative Study MD YEAQUB Research Scholar Aligarh Muslim University, India Email: [email protected] Abstract: This paper will focus on a comparative study about similarities and dissimilarities of the pronunciation between the syllables of English and Arabic with the help of phonetic and phonological tools i.e. manner of articulation, point of articulation and their distribution at different positions in English and Arabic Alphabets. A phonetic and phonological analysis of the alphabets of English and Arabic can be useful in overcoming the hindrances for those want to improve the pronunciation of both English and Arabic languages. We all know that Arabic is a Semitic language from the Afro-Asiatic Language Family. On the other hand, English is a West Germanic language from the Indo- European Language Family. Both languages show many linguistic differences at all levels of linguistic analysis, i.e. phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, etc. For this we will take into consideration, the segmental features only, i.e. the consonant and vowel system of the two languages. So, this is better and larger to bring about pedagogical changes that can go a long way in improving pronunciation and ensuring the occurrence of desirable learners’ outcomes. Keywords: Arabic Alphabets, English Alphabets, Pronunciations, Phonetics, Phonology, manner of articulation, point of articulation. Introduction: We all know that sounds are generally divided into two i.e. consonants and vowels. A consonant is a speech sound, which obstruct the flow of air through the vocal tract. -

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

The Festvox Indic Frontend for Grapheme-To-Phoneme Conversion

The Festvox Indic Frontend for Grapheme-to-Phoneme Conversion Alok Parlikar, Sunayana Sitaram, Andrew Wilkinson and Alan W Black Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, USA aup, ssitaram, aewilkin, [email protected] Abstract Text-to-Speech (TTS) systems convert text into phonetic pronunciations which are then processed by Acoustic Models. TTS frontends typically include text processing, lexical lookup and Grapheme-to-Phoneme (g2p) conversion stages. This paper describes the design and implementation of the Indic frontend, which provides explicit support for many major Indian languages, along with a unified framework with easy extensibility for other Indian languages. The Indic frontend handles many phenomena common to Indian languages such as schwa deletion, contextual nasalization, and voicing. It also handles multi-script synthesis between various Indian-language scripts and English. We describe experiments comparing the quality of TTS systems built using the Indic frontend to grapheme-based systems. While this frontend was designed keeping TTS in mind, it can also be used as a general g2p system for Automatic Speech Recognition. Keywords: speech synthesis, Indian language resources, pronunciation 1. Introduction in models of the spectrum and the prosody. Another prob- lem with this approach is that since each grapheme maps Intelligible and natural-sounding Text-to-Speech to a single “phoneme” in all contexts, this technique does (TTS) systems exist for a number of languages of the world not work well in the case of languages that have pronun- today. However, for low-resource, high-population lan- ciation ambiguities. We refer to this technique as “Raw guages, such as languages of the Indian subcontinent, there Graphemes.” are very few high-quality TTS systems available. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

Schwa Deletion: Investigating Improved Approach for Text-To-IPA System for Shiri Guru Granth Sahib

ISSN (Online) 2278-1021 ISSN (Print) 2319-5940 International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer and Communication Engineering Vol. 4, Issue 4, April 2015 Schwa Deletion: Investigating Improved Approach for Text-to-IPA System for Shiri Guru Granth Sahib Sandeep Kaur1, Dr. Amitoj Singh2 Pursuing M.E, CSE, Chitkara University, India 1 Associate Director, CSE, Chitkara University , India 2 Abstract: Punjabi (Omniglot) is an interesting language for more than one reasons. This is the only living Indo- Europen language which is a fully tonal language. Punjabi language is an abugida writing system, with each consonant having an inherent vowel, SCHWA sound. This sound is modifiable using vowel symbols attached to consonant bearing the vowel. Shri Guru Granth Sahib is a voluminous text of 1430 pages with 511,874 words, 1,720,345 characters, and 28,534 lines and contains hymns of 36 composers written in twenty-two languages in Gurmukhi script (Lal). In addition to text being in form of hymns and coming from so many composers belonging to different languages, what makes the language of Shri Guru Granth Sahib even more different from contemporary Punjabi. The task of developing an accurate Letter-to-Sound system is made difficult due to two further reasons: 1. Punjabi being the only tonal language 2. Historical and Cultural circumstance/period of writings in terms of historical and religious nature of text and use of words from multiple languages and non-native phonemes. The handling of schwa deletion is of great concern for development of accurate/ near perfect system, the presented work intend to report the state-of-the-art in terms of schwa deletion for Indian languages, in general and for Gurmukhi Punjabi, in particular. -

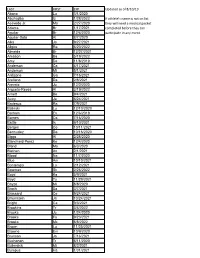

LAST FIRST EXP Updated As of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If Athlete's Name Is Not on List Acevedo Jr

LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If athlete's name is not on list Acevedo Jr. Ma 2/27/2020 they will need a medical packet Adams Br 1/17/2021 completed before they can Aguilar Br 12/6/2020 participate in any event. Aguilar-Soto Al 8/7/2020 Alka Ja 9/27/2021 Allgire Ra 6/20/2022 Almeida Br 12/27/2021 Amason Ba 5/19/2022 Amy De 11/8/2019 Anderson Ca 4/17/2021 Anderson Mi 5/1/2021 Ardizone Ga 7/16/2021 Arellano Da 2/8/2021 Arevalo Ju 12/2/2020 Argueta-Reyes Al 3/19/2022 Arnett Be 9/4/2021 Autry Ja 6/24/2021 Badeaux Ra 7/9/2021 Balinski Lu 12/10/2020 Barham Ev 12/6/2019 Barnes Ca 7/16/2020 Battle Is 9/10/2021 Bergen Co 10/11/2021 Bermudez Da 10/16/2020 Biggs Al 2/28/2020 Blanchard-Perez Ke 12/4/2020 Bland Ma 6/3/2020 Blethen An 2/1/2021 Blood Na 11/7/2020 Blue Am 10/10/2021 Bontempo Lo 2/12/2021 Bowman Sk 2/26/2022 Boyd Ka 5/9/2021 Boyd Ty 11/29/2021 Boyzo Mi 8/8/2020 Brach Sa 3/7/2021 Brassard Ce 9/24/2021 Braunstein Ja 10/24/2021 Bright Ca 9/3/2021 Brookins Tr 3/4/2022 Brooks Ju 1/24/2020 Brooks Fa 9/23/2021 Brooks Mc 8/8/2022 Brown Lu 11/25/2021 Browne Em 10/9/2020 Brunson Jo 7/16/2021 Buchanan Tr 6/11/2020 Bullerdick Mi 8/2/2021 Bumpus Ha 1/31/2021 LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Burch Co 11/7/2020 Burch Ma 9/9/2021 Butler Ga 5/14/2022 Byers Je 6/14/2021 Cain Me 6/20/2021 Cao Tr 11/19/2020 Carlson Be 5/29/2021 Cerda Da 3/9/2021 Ceruto Ri 2/14/2022 Chang Ia 2/19/2021 Channapati Di 10/31/2021 Chao Et 8/20/2021 Chase Em 8/26/2020 Chavez Fr 6/13/2020 Chavez Vi 11/14/2021 Chidambaram Ga 10/13/2019 -

Kharosthi Manuscripts: a Window on Gandharan Buddhism*

KHAROSTHI MANUSCRIPTS: A WINDOW ON GANDHARAN BUDDHISM* Andrew GLASS INTRODUCTION In the present article I offer a sketch of Gandharan Buddhism in the centuries around the turn of the common era by looking at various kinds of evidence which speak to us across the centuries. In doing so I hope to shed a little light on an important stage in the transmission of Buddhism as it spread from India, through Gandhara and Central Asia to China, Korea, and ultimately Japan. In particular, I will focus on the several collections of Kharo~thi manuscripts most of which are quite new to scholarship, the vast majority of these having been discovered only in the past ten years. I will also take a detailed look at the contents of one of these manuscripts in order to illustrate connections with other text collections in Pali and Chinese. Gandharan Buddhism is itself a large topic, which cannot be adequately described within the scope of the present article. I will therefore confine my observations to the period in which the Kharo~thi script was used as a literary medium, that is, from the time of Asoka in the middle of the third century B.C. until about the third century A.D., which I refer to as the Kharo~thi Period. In addition to looking at the new manuscript materials, other forms of evidence such as inscriptions, art and architecture will be touched upon, as they provide many complementary insights into the Buddhist culture of Gandhara. The travel accounts of the Chinese pilgrims * This article is based on a paper presented at Nagoya University on April 22nd 2004. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Early-Alphabets-3.Pdf

Early Alphabets Alphabetic characteristics 1 Cretan Pictographs 11 Hieroglyphics 16 The Phoenician Alphabet 24 The Greek Alphabet 31 The Latin Alphabet 39 Summary 53 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS 1 / 53 Alphabetic characteristics 3,000 BCE Basic building blocks of written language GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 2 / 53 Early visual language systems were disparate and decentralized 3,000 BCE Protowriting, Cuneiform, Heiroglyphs and far Eastern writing all functioned differently Rebuses, ideographs, logograms, and syllabaries · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 3 / 53 HIEROGLYPHICS REPRESENTING THE REBUS PRINCIPAL · BEE & LEAF · SEA & SUN · BELIEF AND SEASON GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 4 / 53 PETROGLYPHIC PICTOGRAMS AND IDEOGRAPHS · CIRCA 200 BCE · UTAH, UNITED STATES GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 5 / 53 LUWIAN LOGOGRAMS · CIRCA 1400 AND 1200 BCE · TURKEY GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 6 / 53 OLD PERSIAN SYLLABARY · 600 BCE GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 7 / 53 Alphabetic structure marked an enormous societal leap 3,000 BCE Power was reserved for those who could read and write · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 8 / 53 What is an alphabet? Definition An alphabet is a set of visual symbols or characters used to represent the elementary sounds of a spoken language. –PM · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / EARLY ALPHABETS / Alphabetic Characteristics 9 / 53 What is an alphabet? Definition They can be connected and combined to make visual configurations signifying sounds, syllables, and words uttered by the human mouth. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

The Carian Language HANDBOOK of ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE the NEAR and MIDDLE EAST

The Carian Language HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-SIX The Carian Language by Ignacio J. Adiego with an appendix by Koray Konuk BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adiego Lajara, Ignacio-Javier. The Carian language / by Ignacio J. Adiego ; with an appendix by Koray Konuk. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 86). Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13 : 978-90-04-15281-6 (hardback) ISBN-10 : 90-04-15281-4 (hardback) 1. Carian language. 2. Carian language—Writing. 3. Inscriptions, Carian—Egypt. 4. Inscriptions, Carian—Turkey—Caria. I. Title. II. P946.A35 2006 491’.998—dc22 2006051655 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 15281 4 ISBN-13 978 90 04 15281 6 © Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Hotei Publishers, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA.