Ulysses: the Novel, the Author and the Translators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1974.Ulysses in Nighttown.Pdf

The- UNIVERSITY· THEAtl\E Present's ULYSSES .IN NIGHTTOWN By JAMES JOYCE Dramatized and Transposed by MARJORIE BARKENTIN Under the Supervision of PADRAIC COLUM Direct~ by GLENN ·cANNON Set and ~O$tume Design by RICHARD MASON Lighting Design by KENNETH ROHDE . Teehnicai.Direction by MARK BOYD \ < THE CAST . ..... .......... .. -, GLENN CANNON . ... ... ... : . ..... ·. .. : ....... ~ .......... ....... ... .. Narrator. \ JOHN HUNT . ......... .. • :.·• .. ; . ......... .. ..... : . .. : ...... Leopold Bloom. ~ . - ~ EARLL KINGSTON .. ... ·. ·. , . ,. ............. ... .... Stephen Dedalus. .. MAUREEN MULLIGAN .......... .. ... .. ......... ............ Molly Bloom . .....;. .. J.B. BELL, JR............. .•.. Idiot, Private Compton, Urchin, Voice, Clerk of the Crown and Peace, Citizen, Bloom's boy, Blacksmith, · Photographer, Male cripple; Ben Dollard, Brother .81$. ·cavalier. DIANA BERGER .......•..... :Old woman, Chifd, Pigmy woman, Old crone, Dogs, ·Mary Driscoll, Scrofulous child, Voice, Yew, Waterfall, :Sutton, Slut, Stephen's mother. ~,.. ,· ' DARYL L. CARSON .. ... ... .. Navvy, Lynch, Crier, Michael (Archbishop of Armagh), Man in macintosh, Old man, Happy Holohan, Joseph Glynn, Bloom's bodyguard. LUELLA COSTELLO .... ....... Passer~by, Zoe Higgins, Old woman. DOYAL DAVIS . ....... Simon Dedalus, Sandstrewer motorman, Philip Beau~ foy, Sir Frederick Falkiner (recorder ·of Dublin), a ~aviour and · Flagger, Old resident, Beggar, Jimmy Henry, Dr. Dixon, Professor Maginni. LESLIE ENDO . ....... ... Passer-by, Child, Crone, Bawd, Whor~. -

Ulysses Notes Joe Kelly Chapter 1: Telemachus Stephen Dedalus, A

Ulysses Notes Joe Kelly Chapter 1: Telemachus Stephen Dedalus, a young poet employed as a school teacher; Buck Mulligan, a med student; and an Englishman called Haines, who is in Ireland to study Celtic culture, spend their morning in their Martello Tower at the seaside resort town of Sandycove, south of Dublin. Stephen, who is mourning for his dead mother, watches Buck shave on the parapet, they discuss things, Buck goes inside to cook breakfast. They all eat while a local farm woman brings them their milk. Then they walk Martello (now called the "Joyce") Tower at down to the "Forty Foot Hole," where Buck Sandycove swims in Dublin Bay. Pay careful attention to what the swimmers say about the Odyssey, Odysseus was missing, Bannons and the photo girl. presumed dead by most, for ten years after the end of the Trojan War, and Look for parallels between Stephen and his palace and wife in Ithaca were Hamlet, on one hand, and Telemachus, the beset by "suitors" who wanted to son of Odysseus, on the other. In the become king. Ulysses is a sequel to Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which is a bildungsroman starring Stephen Dedalus. That novel ended with Stephen graduating from University College, Dublin and heading off for Paris to launch his literary career. Two years later, he's back in Dublin, having been summoned home by his mother's illness. So he's something of an Icarus figure also, having tried to fly out of the labyrinth of Ireland to freed om, but having fallen, so to speak. -

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses Assistant Teacher Haider Ghazi Jassim AL_Jaberi AL.Musawi University of Babylon College of Education Dept. of English Language and Literature [email protected] Abstract Technically accounting, Intertextuality designates the interdependence of a literary text on any literary one in structure, themes, imagery and so forth. As a matter of fact, the term is first coined by Julia Kristeva in 1966 whose contention was that a literary text is not an isolated entity but is made up of a mosaic of quotations, and that any text is the " absorption, and transformation of another"1.She defies traditional notions of the literary influence, saying that Intertextuality denotes a transposition of one or several sign systems into another or others. Transposition is a Freudian term, and Kristeva is pointing not merely to the way texts echo each other but to the way that discourses or sign systems are transposed into one another-so that meanings in one kind of discourses are heaped with meanings from another kind of discourse. It is a kind of "new articulation2". For kriszreve the idea is a part of a wider psychoanalytical theory which questions the stability of the subject, and her views about Intertextuality are very different from those of Roland North and others3. Besides, the term "Intertextuality" describes the reception process whereby in the mind of the reader texts already inculcated interact with the text currently being skimmed. Modern writers such as Canadian satirist W. P. Kinsella in The Grecian Urn4 and playwright Ann-Marie MacDonald in Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet) have learned how to manipulate this phenomenon by deliberately and continually alluding to previous literary works well known to educated readers, namely John Keats's Ode on a Grecian Urn, and Shakespeare's tragedies Romeo and Juliet and Othello respectively. -

Zhou Zuoren's Critique of Violence in Modern China

World Languages and Cultures Publications World Languages and Cultures 2014 The aS cred and the Cannibalistic: Zhou Zuoren’s Critique of Violence in Modern China Tonglu Li Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/language_pubs Part of the Chinese Studies Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ language_pubs/102. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Cultures at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS cred and the Cannibalistic: Zhou Zuoren’s Critique of Violence in Modern China Abstract This article explores the ways in which Zhou Zuoren critiqued violence in modern China as a belief-‐‑driven phenomenon. Differing from Lu Xun and other mainstream intellectuals, Zhou consistently denied the legitimacy of violence as a force for modernizing China. Relying on extensive readings in anthropology, intellectual history, and religious studies, he investigated the fundamental “nexus” between violence and the religious, political, and ideological beliefs. In the Enlightenment’s effort to achieve modernity, cannibalistic Confucianism was to be cleansed from the corpus of Chinese culture as the “barbaric” cultural Other, but Zhou was convinced that such barbaric cannibalism was inherited by the Enlightenment thinkers, and thus made the Enlightenment impossible. -

Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka

Article Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka SPURR, David Anton Abstract This essay considers the work of Joyce and Kafka in terms of paranoia as interpretive delirium, the imagined but internally coherent interpretation of the world whose relation to the real remains undecidable. Classic elements of paranoia are manifest in both writers insofar as their work stages scenes in which the figure of the artist or a subjective equivalent perceives himself as the object of hostility and persecution. Nonetheless, such scenes and the modes in which they are rendered can also be understood as the means by which literary modernism resisted forces hostile to art but inherent in the social and economic conditions of modernity. From this perspective the work of both Joyce and Kafka intersects with that of surrealists like Dali for whom the positive sense of paranoia as artistic practice answered the need for a systematic objectification of the oniric underside of reason, “the world of delirium unknown to rational experience.” Reference SPURR, David Anton. Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka. Journal of Modern Literature , 2011, vol. 34, no. 2, p. 178-191 DOI : 10.2979/jmodelite.34.2.178 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:16597 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka David Spurr Université de Genève This essay considers the work of Joyce and Kafka in terms of paranoia as interpretive delirium, the imagined but internally coherent interpretation of the world whose rela- tion to the real remains undecidable. Classic elements of paranoia are manifest in both writers insofar as their work stages scenes in which the figure of the artist or a subjective equivalent perceives himself as the object of hostility and persecution. -

Joyce's Jewish Stew: the Alimentary Lists in Ulysses

Colby Quarterly Volume 31 Issue 3 September Article 5 September 1995 Joyce's Jewish Stew: The Alimentary Lists in Ulysses Jaye Berman Montresor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 31, no.3, September 1995, p.194-203 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Montresor: Joyce's Jewish Stew: The Alimentary Lists in Ulysses Joyce's Jewish Stew: The Alimentary Lists in Ulysses by JAYE BERMAN MONTRESOR N THEIR PUN-FILLED ARTICLE, "Towards an Interpretation ofUlysses: Metonymy I and Gastronomy: A Bloom with a Stew," an equally whimsical pair ofcritics (who prefer to remain pseudonymous) assert that "the key to the work lies in gastronomy," that "Joyce's overriding concern was to abolish the dietary laws ofthe tribes ofIsrael," and conclude that "the book is in fact a stew! ... Ulysses is a recipe for bouillabaisse" (Longa and Brevis 5-6). Like "Longa" and "Brevis'"interpretation, James Joyce's tone is often satiric, and this is especially to be seen in his handling ofLeopold Bloom's ambivalent orality as a defining aspect of his Jewishness. While orality is an anti-Semitic assumption, the source ofBloom's oral nature is to be found in his Irish Catholic creator. This can be seen, for example, in Joyce's letter to his brother Stanislaus, penned shortly after running off with Nora Barnacle in 1904, where we see in Joyce's attention to mealtimes the need to present his illicit sexual relationship in terms of domestic routine: We get out ofbed at nine and Nora makes chocolate. -

Not the Same Old Story: Dante's Re-Telling of the Odyssey

religions Article Not the Same Old Story: Dante’s Re-Telling of The Odyssey David W. Chapman English Department, Samford University, Birmingham, AL 35209, USA; [email protected] Received: 10 January 2019; Accepted: 6 March 2019; Published: 8 March 2019 Abstract: Dante’s Divine Comedy is frequently taught in core curriculum programs, but the mixture of classical and Christian symbols can be confusing to contemporary students. In teaching Dante, it is helpful for students to understand the concept of noumenal truth that underlies the symbol. In re-telling the Ulysses’ myth in Canto XXVI of The Inferno, Dante reveals that the details of the narrative are secondary to the spiritual truth he wishes to convey. Dante changes Ulysses’ quest for home and reunification with family in the Homeric account to a failed quest for knowledge without divine guidance that results in Ulysses’ destruction. Keywords: Dante Alighieri; The Divine Comedy; Homer; The Odyssey; Ulysses; core curriculum; noumena; symbolism; higher education; pedagogy When I began teaching Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 1990s as part of our new Cornerstone Curriculum, I had little experience in teaching classical texts. My graduate preparation had been primarily in rhetoric and modern British literature, neither of which included a study of Dante. Over the years, my appreciation of Dante has grown as I have guided, Vergil-like, our students through a reading of the text. And they, Dante-like, have sometimes found themselves lost in a strange wood of symbols and allegories that are remote from their educational background. What seems particularly inexplicable to them is the intermingling of actual historical characters and mythological figures. -

James Joyce – Through Film

U3A Dunedin Charitable Trust A LEARNING OPTION FOR THE RETIRED Series 2 2015 James Joyce – Through Film Dates: Tuesday 2 June to 7 July Time: 10:00 – 12:00 noon Venue: Salmond College, Knox Street, North East Valley Enrolments for this course will be limited to 55 Course Fee: $40.00 Tea and Coffee provided Course Organiser: Alan Jackson (473 6947) Course Assistant: Rosemary Hudson (477 1068) …………………………………………………………………………………… You may apply to enrol in more than one course. If you wish to do so, you must indicate your choice preferences on the application form, and include payment of the appropriate fee(s). All applications must be received by noon on Wednesday 13 May and you may expect to receive a response to your application on or about 25 May. Any questions about this course after 25 May should be referred to Jane Higham, telephone 476 1848 or on email [email protected] Please note, that from the beginning of 2015, there is to be no recording, photographing or videoing at any session in any of the courses. Please keep this brochure as a reminder of venue, dates, and times for the courses for which you apply. JAMES JOYCE – THROUGH FILM 2 June James Joyce’s Dublin – a literary biography (50 min) This documentary is an exploration of Joyce’s native city of Dublin, discovering the influences and settings for his life and work. Interviewees include Robert Nicholson (curator of the James Joyce museum), David Norris (Trinity College lecturer and Chair of the James Joyce Cultural Centre) and Ken Monaghan (Joyce’s nephew). -

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce's Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL a Thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingh

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce’s Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY English Studies School of English, Drama, American & Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham October 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers the imbrications created by James Joyce in his writing with the work of John Milton, through allusions, references and verbal echoes. These imbrications are analysed in light of the concept of ‘presence’, based on theories of intertextuality variously proposed by John Shawcross, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, and Eelco Runia. My analysis also deploys Gumbrecht’s concept of stimmung in order to explain how Joyce incorporates a Miltonic ‘atmosphere’ that pervades and enriches his characters and plot. By using a chronological approach, I show the subtlety of Milton’s presence in Joyce’s writing and Joyce’s strategy of weaving it into the ‘fabric’ of his works, from slight verbal echoes in Joyce’s early collection of poems, Chamber Music, to a culminating mass of Miltonic references and allusions in the multilingual Finnegans Wake. -

Dante's Ulysses

7 DANTE'S ULYSSES In a short story entitled "La busca de Averroes,,1 which could be translated as "Averroes' quandary", the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges raises an issue which I would like to take as the point of departure for my talk. A verroes, a 12th century Arabic philosopher, is well known in connection with ])antc as a translator and intcrpreter of Aristotle's work. His brand of radical Aristotelianism, which deviates somewhat from Thomas Aquinas' more orthodox line, definitely had some influence on Dante's thought, but this is only tangential to Borges' story and to the ideas I intend to develop here. The story introduces Averroes in the topical setting of a garden in Cordoba philosophizing with his host, a Moslem prince, and other guests on the nature of poetry. One of the guests has just praised an old poetic metaphor which com pares fate or destiny with a blind camel. Averroes, tired of listening to the argu ment challenging the value of old metaphors, interrupts to state firmly, first, that poetry need not cause us to marvel and, second, that poets are less creators than discovcrers. Having pleased his listeners with his defence of ancient poetry, he then returns to his labour of love, namely the translation and commentary on Aristotle's work which had been keeping him busy for the past several years. Before joining the other guests at the prince's court, Averroes had puzzled ovcr the meaning of two words in Aristotle's Poetirs for which he could find no equiva lent. -

Notes Made in China in May 1990 for the BBC Radio Documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy* Gregory B

Notes made in China in May 1990 for the BBC radio documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy* Gregory B. Lee To cite this version: Gregory B. Lee. Notes made in China in May 1990 for the BBC radio documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy*. 2019. hal-02196338 HAL Id: hal-02196338 https://hal-univ-lyon3.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02196338 Preprint submitted on 28 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Gregory B. Lee. URGENT KNOCKING, China/Hong Kong Notebook, May 1990. Notes made in China in May 1990 in connection with the hour-long radio documentary The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy which I was making for the BBC and which was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on 4the June 1990 to coincide with the 1st anniversary of the massacre at Tiananmen. My Urgent Knocking notebook is somewhat cryptic. I was worried about prying eyes, and the notes were not made in chronological, or consecutive order, but scattered throughout my notebook. Probably, I was hoping that their haphazard pagination would withstand a cursory inspection. -

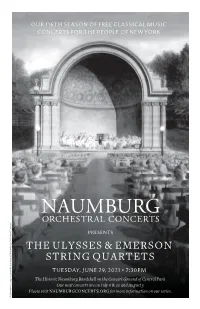

The Ulysses & Emerson String Quartets

OUR 116TH SEASON OF FREE CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERTS FOR THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM The Historic Naumburg Bandshell on the Concert Ground of Central Park Our next concerts are on July 6 & 20 and August 3 Please visit NAUMBURGCONCERTS.ORG for more information on our series. ©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing of Naumburg Orchestral of Naumburg Concert©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM In celebration of 116 years of Free Concerts for the people of New York City - The oldest continuous free outdoor concert series in the world Tonight’s concert is being hosted by classical WQXR - 105.9 FM www.wqxr.org with WQXR host Terrance McKnight NAUMBURG ORCHESTRAL CONCERTS PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS RICHARD STRAUSS, (1864-1949) Sextet from Capriccio, Op. 85, (1942) (performed by the Ulysses Quartet with Lawrence Dutton, viola and Paul Watkins, cello) ANTON BRUCKNER, (1824-1896) String Quintet in F major, WAB 112., (1878-79) Performed by the Emerson String Quartet with Colin Brookes, viola III. Adagio, G-flat major, common time -INTERMISSION- DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH, (1906-1975) Two Pieces for String Octet, Op. 11, (1924-25) Performed with the Ulysses Quartet playing the first parts 1. Adagio 2. Allegro molto FELIX MENDELSSOHN, (1809-1847 Octet in E-flat major, Op. 20, (1825) 1. Allegro moderato ma con fuoco (E-flat major) 2. Andante (C minor) 3. Scherzo: Allegro leggierissimo (G minor) 4. Presto (E-flat major) The performance of The Ulysses and Emerson String Quartets has been made possible by a generous grant from The Arthur Loeb Foundation The summer season of 2021 honors the memory of our past President, MICHELLE R.