Notes Made in China in May 1990 for the BBC Radio Documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy* Gregory B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INVERSE TRANSLATION in CHINA: a NECESSARY CHOICE OR a NECESSARY EVIL By

ARTICLES INVERSE TRANSLATION IN CHINA: A NECESSARY CHOICE OR A NECESSARY EVIL By JIASHENG SHI Associate Professor and Director of Translation Department, School of Translation and Interpreting, Jinan University, Zhuhai, China. ABSTRACT Inverse translation has long been seen in the negative light in modern translation studies, and has thus been relegated to a sort of second class endeavour. Based on a brief comparative study of English translations of Wenxin Diaolong1, a Chinese literary classic, this paper argues that inverse translation is as legitimate and feasible as direct translation in China, and that the assessment of quality of translation should be based more on the translator's translation competence and translation strategy than on his or her language affiliation. Keywords: Inverse Translation, Direct Translation, Wenxin Diaolong. INTRODUCTION for translation practice that is conducted from a foreign Inverse translation is “a term used to describe a translation, language into one's mother tongue—if they take into either written or spoken, which is done from the translator's account translation practice at all. This biased stance native language, or language of habitual use” concerning inverse translation is not conducive to the (Shuttleworth & Cowie 1997: 90). It is the opposite of direct development of translation studies, and runs contrary to translation, which refers to the translation done into the translation reality, where translation from one's mother translator's native language, or language of habitual use tongue into a foreign language is possible, permissible and (Shuttleworth & Cowie 1997: 41). Inverse translation is also some times even desirable. named “service translation” (Newmark 1988: 52). -

Zhou Zuoren's Critique of Violence in Modern China

World Languages and Cultures Publications World Languages and Cultures 2014 The aS cred and the Cannibalistic: Zhou Zuoren’s Critique of Violence in Modern China Tonglu Li Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/language_pubs Part of the Chinese Studies Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ language_pubs/102. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Cultures at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS cred and the Cannibalistic: Zhou Zuoren’s Critique of Violence in Modern China Abstract This article explores the ways in which Zhou Zuoren critiqued violence in modern China as a belief-‐‑driven phenomenon. Differing from Lu Xun and other mainstream intellectuals, Zhou consistently denied the legitimacy of violence as a force for modernizing China. Relying on extensive readings in anthropology, intellectual history, and religious studies, he investigated the fundamental “nexus” between violence and the religious, political, and ideological beliefs. In the Enlightenment’s effort to achieve modernity, cannibalistic Confucianism was to be cleansed from the corpus of Chinese culture as the “barbaric” cultural Other, but Zhou was convinced that such barbaric cannibalism was inherited by the Enlightenment thinkers, and thus made the Enlightenment impossible. -

Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture

In &a r*tm Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture edited by Sucheng Chan Exclusion and the Chinese Communify in America, r88z-ry43 Edited by Sucheng Chan Also in the series: Gary Y. Okihiro, Cane Fires: The Anti-lapanese Moaement Temple University press in Hawaii, t855-ry45 Philadelphia Chapter 6 The Kuomintang in Chinese American Kuomintang in Chinese American Communities 477 E Communities before World War II the party in the Chinese American communities as they reflected events and changes in the party's ideology in China. The Chinese during the Exclusion Era The Chinese became victims of American racism after they arrived in Him Lai Mark California in large numbers during the mid nineteenth century. Even while their labor was exploited for developing the resources of the West, they were targets of discriminatory legislation, physical attacks, and mob violence. Assigned the role of scapegoats, they were blamed for society's multitude of social and economic ills. A populist anti-Chinese movement ultimately pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the first Chinese exclusion act in 1882. Racial discrimination, however, was not limited to incoming immi- grants. The established Chinese community itself came under attack as The Chinese settled in California in the mid nineteenth white America showed by words and deeds that it considered the Chinese century and quickly became an important component in the pariahs. Attacked by demagogues and opportunistic politicians at will, state's economy. However, they also encountered anti- Chinese were victimizedby criminal elements as well. They were even- Chinese sentiments, which culminated in the enactment of tually squeezed out of practically all but the most menial occupations in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. -

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Zhu, Yingyue Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 14:07:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642043 MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING by Yingyue Zhu ____________________________ Copyright © Yingyue Zhu 2020 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Yingyue Zhu, titled MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Master’s Degree. Jun 29, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Dian Li Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Scott Gregory Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Master’s requirement. -

Ulysses: the Novel, the Author and the Translators

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 21-27, January 2011 © 2011 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.1.1.21-27 Ulysses: The Novel, the Author and the Translators Qing Wang Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—A novel of kaleidoscopic styles, Ulysses best displays James Joyce’s creativity as a renowned modernist novelist. Joyce maneuvers freely the English language to express a deep hatred for religious hypocrisy and colonizing oppressions as well as a well-masked patriotism for his motherland. In this aspect Joyce shares some similarity with his Chinese translator Xiao Qian, also a prolific writer. Index Terms—style, translation, Ulysses, James Joyce, Xiao Qian I. INTRODUCTION James Joyce (1882-1941) is regarded as one of the most innovative novelists of the 20th century. For people who are interested in modernist novels, Ulysses is an enormous aesthetic achievement. Attridge (1990, p.1) asserts that the impact of Joyce‟s literary revolution was such that “far more people read Joyce than are aware of it”, and that few later novelists “have escaped its aftershock, even when they attempt to avoid Joycean paradigms and procedures.” Gillespie and Gillespie (2000, p.1) also agree that Ulysses is “a work of art rivaled by few authors in this or any century.” Ezra Pound was one of the first to recognize the gift in Joyce. He was convinced of the greatness of Ulysses no sooner than having just read the manuscript for the first part of the novel in 1917. -

Translation of English and Chinese Addressing Terms from the Cultural Aspect

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 1, No. 5, pp. 738-742, September 2010 © 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/jltr.1.5.738-742 Translation of English and Chinese Addressing Terms from the Cultural Aspect Chunli Yang Foreign Languages School, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—Terms of address are frequently used in social communication to show the identity, rank and relationship between the speaker and the hearer. It is important to have a profound understanding of addressing terms, especially in cross-cultural communication. However, due to the difference in history, religion and culture, terms of address vary in different countries and regions. In this paper, the author discusses the translation of English and Chinese addressing terms from the aspect of cultural background. First, the author defines terms of address and gives the reason why people use terms of address in social communication. Then, the differences between English and Chinese terms of address are analyzed from the point of kinship terms and social terms of address. Last, four translation methods are given according to different situations, namely, literal translation, translating flexibly, specification or generalization and domestication and foreignization. Index Terms—terms of address, kinship terms, social terms of address, translation methods I. INTRODUCTION With the development of globalization and the expansion of the intercultural communication, the contact between people from different countries, cultures and races are becoming more and more frequent. In the communication, it is inevitable to use terms of address which differ because of the diversity of culture. -

Gregory Lee CV 1

Gregory Lee CV Curriculum vitae GREGORY B. LEE 利大英 Professor of Chinese and Transcultural Studies, Université de Lyon – Jean Moulin (since 1999) Director, Institut d’Etudes Transtextuelles et Transculturelles (Institute for Transtextual and Transcultural Studies — IETT) Fellow of the Hong Kong Academy of the Humanities Chevalier de l’ordre des Palmes académiques Nationalities: British & French Languages: English (native), Chinese (near native), French (near native); Spanish (good); Portuguese, Italian (reading) PREVIOUS AND VISITING POSTS 05.2018 ; 03.2019 Visiting Professor, Sun Yat-sen University, Canton, China 2010-2012 Chair Professor of Chinese & Transcultural Studies, City University of Hong Kong Founding Director, Hong Kong Advanced Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Studies 2005-2010 Honorary Visiting Professor, University of Wuhan, China 1998-1999 Visiting Professor, University of Lyon (Jean Moulin) 1994-1998 Associate Professor, Department of Comparative Literature, University of Hong Kong 1990-1994 Assistant Professor, East Asian Languages & Civilizations, University of Chicago 1987-1988 Lecturer (temporary), Department of East Asia School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1983-1984 Supervisor, Faculty of Oriental Studies Cambridge University OTHER PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1988-1990 Asia Specialist (report writer and broadcaster), BBC World Service 1986-1987 Editor, Foreign Languages Press (SINOLINGUA Chinese as a second language), Beijing 1983-1984 Acting Head, Far Eastern Library, Cambridge University 1 Gregory -

Two Poems Chen Li Translated by Elaine Wong

Special Focus Chinese Contemporary Poetry Two Poems Chen Li Translated by Elaine Wong The two poems included here are from Elaine Wong’s project translating Chen Li’s poetry. “I Run into Monet in Monet’s Garden” imagines a conversation with Monet on the redemptive power of art in times of personal suffering. Wong’s recent viewing of the wall-sized Water Lilies by Monet at the Met brought some breakthroughs to this translation, especially to the wordplay on “water lily” and to the transition from pain to beauty. “Rivers North of the Future” portrays Chen Li’s friendship with the Beijing poet Wang Jiaxin as well as his aspiration for sincere poetic exchanges between Taiwan and mainland China. Meeting both poets in summer 2018 helped Wong better understand the poets’ relationship and their poems. CHINESE LITERATURE TODAY VOL . 8 NO . 1 97 I Run into Monet in Monet’s Garden I run into Monet in Monet’s Garden. He asks, “Did But your eyesight is deteriorating. (Is there you come a cataract?) from the Orangerie, where lianhua ponds line the Can you see light sharply with your eyes? oval walls?” “I also use my mind’s eye. I can see I say, I came from Hualien, the opposite direction. the wrinkles in flowing water. That Your is immortal youth . ” Japanese footbridge brought me here. You came up I came under physical and emotional pain, against and encountered a depression as heavy, or light, poverty, and you lost two wives and your eldest son as ocean and sky blue. Can I turn Hualien, my in his prime. -

The Becoming Self-Conscious of Zawen”: Literary Modernity and Politics of Language in Lu Xun’S Essay Production During His Transitional Period

Front. Lit. Stud. China 2014, 8(3): 374−409 DOI 10.3868/s010-003-014-0021-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Xudong ZHANG “The Becoming Self-Conscious of Zawen”: Literary Modernity and Politics of Language in Lu Xun’s Essay Production during His Transitional Period Abstract While Lu Xun’s early works of fiction have long established his literary reputation, this article focuses on the form and content of his zawen essays written several years later, from 1925 to 1927. Examining the zawen from Huagai ji, Huagai ji xubian (sequel), and Eryi ji (Nothing more), the author views these as “transitional” essays which demonstrate an emergent self-consciousness in Lu Xun’s writing. Through close reading of a selection of these essays, the author considers the ways in which they point toward a state of crisis for Lu Xun, as well as a means of tackling his sense of passivity and “petty matters.” This crisis-state ultimately yields a new literary form unique to the era, a form which represents a crucial source of Chinese modernity. From sheer impossibility and a “negating spirit” emerges a new and life-affirming possibility of literary experience. Keywords Lu Xun, zawen, crisis, consciousness, revolution, education, writing Introduction We might say the basic contours of the figure of Lu Xun can ultimately be determined through his zawen writings. A great deal of preparatory work must be done in order to address these zawen in their entirety. Today I will speak of what I deem to be the “transitional phase” of two or three collected zawen works, in order to determine whether several characteristics of Lu Xun’s zawen writings can be summed up therein. -

Read the Introduction

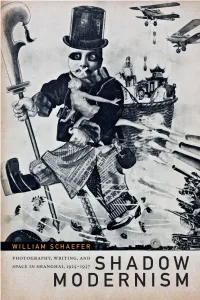

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

Virginia Woolf Miscellany, Issue 53, Spring 1999

\1r 1nia Woo /\1sce an Number 53 Spring 1999 TO THE READERS: on language from 1927 through 1929, then it would seem that our Regarding this issue, a few recollections on miscellaneous. sp~culations about influence should cut the other way. As Caughie What inspired the title of VWM, some time before the Fall Issue of pomts out, early Wittgenstein remained faithful to the traditional 1973, was a wideness of spirit Peggy Comstock, Ellen Hawkes correspondence theory of truth, "seeking a correspondence between Rogat, JJ Wilson and I associated with Virginia Woolf. Seeking to word and world" (2), but if we accept Caughie's reading of Woolf's be inclusive rather than exclusive, we sent out a questionnaire and late twenties writings, then it would seem that Wittgenstein had a lot the first TO THE READERS invited all to participate in future to learn from Woolf about language games, and not vice versa. And "editorial" decisions. Agreeing that "nothing was simply one even if we acknowledge that Wittgenstein reconsiders his early phi thing," from the outset we encouraged the miscellaneous. So back, losophy, it appears that his rejection comes after Woolf's central for one issue at least, to our origins. works on language had already been written-Caughie dates his Lucio Ruotolo rethinking in the 1930' s. Questioning the directionality of influence is Stanford University also an issue when considering Ruotolo's 1973 discussion of Mrs. Dalloway. Woolf seems to have had firmly in place by the time she Indeed, the Fall '99 issue of VWM is devoted to a theme, trans wrote her 1925 novel a philosophy which focuses on "the experience lation, and Pat Laurence has heard from a number of different of seeing the world as a miracle," an insight which Wittgenstein countries and languages already, but has extended her deadline to makes public in 1929or1930. -

English Translations of Shen Congwen's Masterwork

English Translations of Shen Congwen’s Masterwork, Bian Cheng (Border Town) ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS OF SHEN CONGWEN’S MASTERWORK, BIAN CHENG (BORDER TOWN) Jeffrey C. KINKLEY St. John’s University, New York City 8000 Utopia Parkway, Jamaica, NY 11439, USA [email protected] This essay compares the four published English translations of Bian cheng (Border Town) of Shen Congwen’s novel, discussing personal, linguistic, social, political, historical, and cross- cultural factors that might have influenced the translations and their reception when they appeared, respectively, in 1936, 1947, 1962, and 2009. Key words: Shen Congwen, Bian cheng, Border Town, Frontier City, translation, dialect, West Hunan, reception, Cuicui, Pearl Buck, Nobel Prize Shen Congwen’s 沈從文short novel Bian cheng 邊城, composed in 1933 − 1934, first published serially in Chinese in 1934,1 and translated under titles including Border Town (my own translation, which I shall privilege in this essay), The Frontier City, Une bourgade a l’écart (Fr.: An outlying town), Le passeur de Chadong (Fr.: The ferryman of Chadong), and Die Grenzstadt (Ger.: The frontier city), has for more than seven decades been acclaimed as Shen Congwen’s masterwork. That is the view in China and globally. 2 In China, biographical dictionaries from the 1930s to 1949 commonly (though not always 1 SHEN CONGWEN (1902 − 1988), Bian cheng, first published in the Guowen zhoupao 國聞週報. The initial installment appeared on 1 January 1934, yet the final installment bears a note indicating that Shen finished the work only on 19 April 1934. 2 I wish to thank Professor Gang Zhou (Zhou Gang 周刚) of Louisiana State University for organizing a panel on the “Global Shen Congwen” at the July 2013 conference of the International Comparative Literature Association in Paris.