Early Speech Perception and Later Language Development: Implications for the “Critical Period”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Period for Second Language Acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 Million English Speakers ⁎ Joshua K

Cognition xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cognition journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cognit Original Articles A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers ⁎ Joshua K. Hartshornea,b, , Joshua B. Tenenbauma, Steven Pinkerc a Department of Brain & Cognitive Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Building 46, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, MIT, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States b Department of Psychology, Boston College, McGuinn Hall 527, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467, United States c Department of Psychology, Harvard University, William James Hall 970, 33 Kirkland St., Cambridge, MA 02138, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Children learn language more easily than adults, though when and why this ability declines have been obscure Language acquisition for both empirical reasons (underpowered studies) and conceptual reasons (measuring the ultimate attainment Critical period of learners who started at different ages cannot by itself reveal changes in underlying learning ability). We L2 acquisition address both limitations with a dataset of unprecedented size (669,498 native and non-native English speakers) and a computational model that estimates the trajectory of underlying learning ability by disentangling current age, age at first exposure, and years of experience. This allows us to provide the first direct estimate of how grammar-learning ability changes with age, finding that it is preserved almost to the crux of adulthood (17.4 years old) and then declines steadily. This finding held not only for “difficult” syntactic phenomena but also for “easy” syntactic phenomena that are normally mastered early in acquisition. The results support the existence of a sharply-defined critical period for language acquisition, but the age of offset is much later than previously speculated. -

Download Article (PDF)

Libri Phonetica 1999;56:105–107 = Part I, ‘Introduction’, includes a single Winifred Strange chapter written by the editor. It is an Speech Perception and Linguistic excellent historical review of cross-lan- Experience: Issues in Cross-Language guage studies in speech perception pro- Research viding a clear conceptual framework of York Press, Timonium, 1995 the topic. Strange presents a selective his- 492 pp.; $ 59 tory of research that highlights the main ISBN 0–912752–36–X theoretical themes and methodological paradigms. It begins with a brief descrip- How is speech perception shaped by tion of the basic phenomena that are the experience with our native language and starting points for the investigation: the by exposure to subsequent languages? constancy problem and the question of This is a central research question in units of analysis in speech perception. language perception, which emphasizes Next, the author presents the principal the importance of crosslinguistic studies. theories, methods, findings and limita- Speech Perception and Linguistic Experi- tions in early cross-language research, ence: Issues in Cross-Language Research focused on categorical perception as the contains the contributions to a Workshop dominant paradigm in the study of adult in Cross-Language Perception held at the and infant perception in the 1960s and University of South Florida, Tampa, Fla., 1970s. Finally, Strange reviews the most USA, in May 1992. important findings and conclusions in This text may be said to represent recent cross-language research (1980s and the first compilation strictly focused on early 1990s), which yielded a large theoretical and methodological issues of amount of new information from a wider cross-language perception research. -

The Evolution of the Critical Period for Language Acquisition:'

Cognifion. 40( 1991) 159-201 The evolution of the critical period for language acquisition:’ Received March 14. 1990. final revision accepted May 15, 1991 Abstract Hurford. J.R.. IYYI. The evolution of the critical period for language acqukition. Cognition. 10: 159-201. E\.idence suggests that there is a critical, or at least a setuiti1.e. period for language acquisition, which ends around puberty. The existence of this perioti is explained by an evolutionary model which assumes that (a) linguistic ability is in principle (if not in practice) measurable, and (b) the amount of language controlled by at1 individual conferred selective advantage on it. In this model. the language fault? is seen as adaptive, favoured by natural selection. bthile tfle critical period for language acquisition itself is not an adaptation, but arises from the interplay of genetic factors influencing life-history characters in relation to language acqnisitiotl. The evolutionary model is implemented on a computer and simulations of popula- tions evolving under various plausible. if idealized, conditions result in clear critical period effects, which end around puberty. 1. The phenomenon to he explained A body of evidence suggests that there is in humans a critical period, or at least a sensitive period, for the acquisition of (first) language. The critical period hypothesis was most prominently advanced by Lenneberg (1967), a work which *I thank the following for helpful discussion or comments on this paper: Jean Aitchison. Ellen Bard. James Cooke Brown. Phil Carr. Peter Caryl, Grev Corbett. Tim Ingold, Steve Isard. Aubrey Manning, David Smillie, John Maynard Smith, Jim Monaghan. -

Role of Perineuronal Nets in Neural Plasticity

The Journal of Neuroscience, November 9, 2016 • 36(45):11459–11468 • 11459 Mini-Symposium Casting a Wide Net: Role of Perineuronal Nets in Neural Plasticity Barbara A. Sorg,1 XSabina Berretta,2 XJordan M. Blacktop,1 XJames W. Fawcett,3 XHiroshi Kitagawa,4 X Jessica C.F. Kwok,5 and XMarta Miquel6 1Department of Integrative Physiology and Neuroscience, Translational Addiction Research Center, Washington State University, Vancouver, Washington 98686, 2Translational Neuroscience Laboratory, McLean Hospital, Mailman Research Center, Belmont, Massachusetts 02478, 3John van Geest Centre for Brain Repair, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 0SP, United Kingdom, 4Department of Biochemistry, Kobe Pharmaceutical, University, Kobe 658-8558, Japan, 5School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom, and 6Faculty of Health Sciences, Psychobiology, Universitat Jaume I, 12071 Castello´n de la Plana, Spain Perineuronal nets (PNNs) are unique extracellular matrix structures that wrap around certain neurons in the CNS during development and control plasticity in the adult CNS. They appear to contribute to a wide range of diseases/disorders of the brain, are involved in recovery from spinal cord injury, and are altered during aging, learning and memory, and after exposure to drugs of abuse. Here the focus isonhowamajorcomponentofPNNs,chondroitinsulfateproteoglycans,controlplasticity,andontheroleofPNNsinmemoryinnormal aging, in a tauopathy model of Alzheimer’s disease, and in drug addiction. Also discussed is how altered extracellular matrix/PNN formation during development may produce synaptic pathology associated with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, and autism spectrum disorders. Understanding the molecular underpinnings of how PNNs are altered in normal physiology and disease will offer insights into new treatment approaches for these diseases. -

An Extracellular Perspective on CNS Maturation: Perineuronal Nets and the Control of Plasticity

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review An Extracellular Perspective on CNS Maturation: Perineuronal Nets and the Control of Plasticity Daniela Carulli 1,2,* and Joost Verhaagen 1 1 Laboratory for Neuroregeneration, Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, Royal Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1105 BA Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] 2 Department of Neuroscience Rita Levi-Montalcini and Neuroscience Institute Cavalieri Ottolenghi, University of Turin, 10040 Turin, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: During restricted time windows of postnatal life, called critical periods, neural circuits are highly plastic and are shaped by environmental stimuli. In several mammalian brain areas, from the cerebral cortex to the hippocampus and amygdala, the closure of the critical period is dependent on the formation of perineuronal nets. Perineuronal nets are a condensed form of an extracellular matrix, which surrounds the soma and proximal dendrites of subsets of neurons, enwrapping synaptic terminals. Experimentally disrupting perineuronal nets in adult animals induces the reactivation of critical period plasticity, pointing to a role of the perineuronal net as a molecular brake on plasticity as the critical period closes. Interestingly, in the adult brain, the expression of perineuronal nets is remarkably dynamic, changing its plasticity-associated conditions, including memory processes. In this review, we aimed to address how perineuronal nets contribute to the maturation of brain circuits and the regulation of adult brain plasticity and memory processes in physiological and pathological conditions. Citation: Carulli, D.; Verhaagen, J. An Extracellular Perspective on CNS Keywords: perineuronal net; critical period; chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans; learning; memory; Maturation: Perineuronal Nets and Alzheimer’s disease; drug addiction the Control of Plasticity. -

Relations Between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations

14 Relations between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations Willem J. M. Levelt One Agent, Two Modalities There is a famous book that never appeared: Bever and Weksel (shelved). It contained chapters by several young Turks in the budding new psycho- linguistics community of the mid-1960s. Jacques Mehler’s chapter (coau- thored with Harris Savin) was entitled “Language Users.” A normal language user “is capable of producing and understanding an infinite number of sentences that he has never heard before. The central problem for the psychologist studying language is to explain this fact—to describe the abilities that underlie this infinity of possible performances and state precisely how these abilities, together with the various details . of a given situation, determine any particular performance.” There is no hesi tation here about the psycholinguist’s core business: it is to explain our abilities to produce and to understand language. Indeed, the chapter’s purpose was to review the available research findings on these abilities and it contains, correspondingly, a section on the listener and another section on the speaker. This balance was quickly lost in the further history of psycholinguistics. With the happy and important exceptions of speech error and speech pausing research, the study of language use was factually reduced to studying language understanding. For example, Philip Johnson-Laird opened his review of experimental psycholinguistics in the 1974 Annual Review of Psychology with the statement: “The fundamental problem of psycholinguistics is simple to formulate: what happens if we understand sentences?” And he added, “Most of the other problems would be half way solved if only we had the answer to this question.” One major other 242 W. -

Colored-Speech Synaesthesia Is Triggered by Multisensory, Not Unisensory, Perception Gary Bargary,1,2,3 Kylie J

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Report Colored-Speech Synaesthesia Is Triggered by Multisensory, Not Unisensory, Perception Gary Bargary,1,2,3 Kylie J. Barnett,1,2,3 Kevin J. Mitchell,2,3 and Fiona N. Newell1,2 1School of Psychology, 2Institute of Neuroscience, and 3Smurfit Institute of Genetics, Trinity College Dublin ABSTRACT—Although it is estimated that as many as 4% of sistent terminology reflects an underlying lack of understanding people experience some form of enhanced cross talk be- about the amount of information processing required for syn- tween (or within) the senses, known as synaesthesia, very aesthesia to be induced. For example, several studies have little is understood about the level of information pro- found that synaesthesia can occur very rapidly (Palmeri, Blake, cessing required to induce a synaesthetic experience. In Marois, & Whetsell, 2002; Ramachandran & Hubbard, 2001; work presented here, we used a well-known multisensory Smilek, Dixon, Cudahy, & Merikle, 2001) and is sensitive to illusion called the McGurk effect to show that synaesthesia changes in low-level properties of the inducing stimulus, such as is driven by late, perceptual processing, rather than early, contrast (Hubbard, Manoha, & Ramachandran, 2006) or font unisensory processing. Specifically, we tested 9 linguistic- (Witthoft & Winawer, 2006). These findings suggest that syn- color synaesthetes and found that the colors induced by aesthesia is an automatic association driven by early, unisensory spoken words are related to what is perceived (i.e., the input. However, attention, semantic information, and feature- illusory combination of audio and visual inputs) and not to binding processes (Dixon, Smilek, Duffy, Zanna, & Merikle, the auditory component alone. -

Perception and Awareness in Phonological Processing: the Case of the Phoneme

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/222609954 Perception and awareness in phonological processing: the case of the phoneme ARTICLE in COGNITION · APRIL 1994 Impact Factor: 3.63 · DOI: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90032-9 CITATIONS DOWNLOADS VIEWS 67 45 94 2 AUTHORS: José Morais Regine Kolinsky Université Libre de Bruxelles Université Libre de Bruxelles 92 PUBLICATIONS 1,938 CITATIONS 103 PUBLICATIONS 1,571 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Regine Kolinsky Retrieved on: 15 July 2015 Cognition, 50 (1994) 287-297 OOlO-0277/94/$07.00 0 1994 - Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Perception and awareness in phonological processing: the case of the phoneme JosC Morais*, RCgine Kolinsky Laboratoire de Psychologie exptrimentale, Universitt Libre de Bruxelles, Av. Ad. Buy1 117, B-l 050 Bruxelles, Belgium Abstract The necessity of a “levels-of-processing” approach in the study of mental repre- sentations is illustrated by the work on the psychological reality of the phoneme. On the basis of both experimental studies of human behavior and functional imaging data, it is argued that there are unconscious representations of phonemes in addition to conscious ones. These two sets of mental representations are func- tionally distinct: the former intervene in speech perception and (presumably) production; the latter are developed in the context of learning alphabetic literacy for both reading and writing purposes. Moreover, among phonological units and properties, phonemes may be the only ones to present a neural dissociation at the macro-anatomic level. Finally, it is argued that even if the representations used in speech perception and those used in assembling and in conscious operations are distinct, they may entertain dependency relations. -

What's Critical for the Minireview Critical Period in Visual Cortex?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Cell, Vol. 99, 673±676, December 23, 1999, Copyright 1999 by Cell Press What's Critical for the Minireview Critical Period in Visual Cortex? Lawrence C. Katz adults had virtually no effect. Subsequent anatomical Howard Hughes Medical Institute and tracing revealed that the imbalance of activity resulted Department of Neurobiology in the actual loss of synaptic inputs from the thalamic Duke University Medical Center regions representing the closed eye, and expansion of Durham, North Carolina 27710 those representing the open eye (Figure 1B). While in normal primates and cats, the thalamic inputs represent- ing the two eyes parse cortical layer 4 into alternating, During a brief period in postnatal life, sensory experi- equal-sized stripes, eye closure during the critical period ences indelibly shape the behavior of many vertebrate reduced the cortical territory of the closed eye to species. Salmon learn their natal rivers, birds learn their shrunken broken stripes, with its former territory now father's songs, and humans acquire language based invaded by inputs representing the other eye (Hubel et on particular sensory experiences during such ªcritical al., 1977). Behaviorally, animals monocularly deprived periods.º Early ethological investigations of critical peri- ods focused on the behavioral consequences of early sensory experiences, but how and where such experi- ences were permanently etched into brain circuits was unknown. The notion that critical periods actually repre- sented heightened epochs of brain plasticity, and that ex- perience could produce permanent, large-scale changes in neuronal circuits emerged from Hubel and Wiesel's investigations in the cat and monkey visual cortex begin- ning in the mid-1960s (Hubel and Wiesel, 1970). -

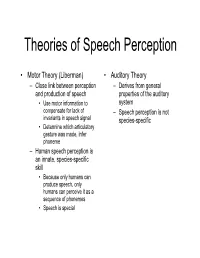

Theories of Speech Perception

Theories of Speech Perception • Motor Theory (Liberman) • Auditory Theory – Close link between perception – Derives from general and production of speech properties of the auditory • Use motor information to system compensate for lack of – Speech perception is not invariants in speech signal species-specific • Determine which articulatory gesture was made, infer phoneme – Human speech perception is an innate, species-specific skill • Because only humans can produce speech, only humans can perceive it as a sequence of phonemes • Speech is special Wilson & friends, 2004 • Perception • Production • /pa/ • /pa/ •/gi/ •/gi/ •Bell • Tap alternate thumbs • Burst of white noise Wilson et al., 2004 • Black areas are premotor and primary motor cortex activated when subjects produced the syllables • White arrows indicate central sulcus • Orange represents areas activated by listening to speech • Extensive activation in superior temporal gyrus • Activation in motor areas involved in speech production (!) Wilson and colleagues, 2004 Is categorical perception innate? Manipulate VOT, Monitor Sucking 4-month-old infants: Eimas et al. (1971) 20 ms 20 ms 0 ms (Different Sides) (Same Side) (Control) Is categorical perception species specific? • Chinchillas exhibit categorical perception as well Chinchilla experiment (Kuhl & Miller experiment) “ba…ba…ba…ba…”“pa…pa…pa…pa…” • Train on end-point “ba” (good), “pa” (bad) • Test on intermediate stimuli • Results: – Chinchillas switched over from staying to running at about the same location as the English b/p -

Effects of Language on Visual Perception

Effects of Language on Visual Perception Gary Lupyan1a, Rasha Abdel Rahmanb, Lera Boroditskyc, Andy Clarkd aUniversity of Wisconsin-Madison bHumboldt-Universität zu Berlin cUniversity of California San Diego dUniversity of Sussex Abstract Does language change what we perceive? Does speaking different languages cause us to perceive things differently? We review the behavioral and elec- trophysiological evidence for the influence of language on perception, with an emphasis on the visual modality. Effects of language on perception can be observed both in higher-level processes such as recognition, and in lower-level processes such as discrimination and detection. A consistent finding is that language causes us to perceive in a more categorical way. Rather than being fringe or exotic, as they are sometimes portrayed, we discuss how effects of language on perception naturally arise from the interactive and predictive nature of perception. Keywords: language; perception; vision; categorization; top-down effects; prediction “Even comparatively simple acts of perception are very much more at the mercy of the social patterns called words than we might suppose.” [1]. “No matter how influential language might be, it would seem preposter- ous to a physiologist that it could reach down into the retina and rewire the ganglion cells” [2]. 1Correspondence: [email protected] Preprint submitted to Trends in Cognitive Sciences August 22, 2020 Language as a form of experience that affects perception What factors influence how we perceive the world? For example, what makes it possible to recognize the object in Fig. 1a? Or to locate the ‘target’ in Fig. 1b? Where is the head of the bird in Fig. -

How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F

Language and Linguistics Compass 2/6 (2008): 1149–1170, 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00089.x How Infant Speech Perception Contributes to Language Acquisition Judit Gervain* and Janet F. Werker University of British Columbia Abstract Perceiving the acoustic signal as a sequence of meaningful linguistic representations is a challenging task, which infants seem to accomplish effortlessly, despite the fact that they do not have a fully developed knowledge of language. The present article takes an integrative approach to infant speech perception, emphasizing how young learners’ perception of speech helps them acquire abstract structural properties of language. We introduce what is known about infants’ perception of language at birth. Then, we will discuss how perception develops during the first 2 years of life and describe some general perceptual mechanisms whose importance for speech perception and language acquisition has recently been established. To conclude, we discuss the implications of these empirical findings for language acquisition. 1. Introduction As part of our everyday life, we routinely interact with children and adults, women and men, as well as speakers using a dialect different from our own. We might talk to them face-to-face or on the phone, in a quiet room or on a busy street. Although the speech signal we receive in these situations can be physically very different (e.g., men have a lower-pitched voice than women or children), we usually have little difficulty understanding what our interlocutors say. Yet, this is no easy task, because the mapping from the acoustic signal to the sounds or words of a language is not straightforward.